Chapter 10

A LOOK BACK BEFORE GOING FORWARD:

THE WEST

Authors’ Note (April, 2014): Given the recent clear examples of ideological disagreements between Russia and the US—as evidenced by the statements and actions of Vladimir Putin and Barack Obama—and military actions by both countries, one has to wonder if the end of the Cold War was really only a suspension. It may be that this section is already obsolete even as we prepare for publication. Let’s hope not!

T

he world was turned upside down at the beginning of the 1990s. The communist bloc fell apart, followed by the Soviet Union, itself. The political and ideological confrontation between two opposing social systems vanished. “Enemies” disappeared. The Cold War was over, at least the one between the USA and USSR. This turned out to be more brazenly effective than the magic of Merlin or that of the ancient Egyptian soothsayers. Only yesterday, there were plenty of “wild Russians” and “aggressive American imperialists” ready to devour one another, but suddenly they were all gone. People everywhere turned out to be the same, and to have the same aspirations, desires, joys, troubles, and concerns. It became apparent that no one wanted to attack anyone else, and never did.

What sort of ESP miracle can compare to this?

It’s likely curious to many that none of the psychics, including the famous ones, were able to accurately predict these global events, at least publicly. People identifying themselves as psychics certainly made predictions as they

always do, but their forecasts lacked exact (or even close) dates and details, making the predictions essentially useless. One has to wonder whether predictions are necessary at all, especially given that many psychics won’t even go there, claiming the future is not set in stone and therefore always includes an element of unpredictability (and a good chance for them to be “wrong”). Yet human beings do want to know the Future—we consult a sort of “oracle” every day that even helps us plan our day and especially our wardrobe (you know—the weather-guy/gal on TV or radio or the Internet).

In the West, research supports the vagaries of predictions. In carefully designed experiments, we find that remote viewers appear to have statistical access to possible, even probable, futures that are likely to occur, even if in actuality they do not.

So there were no ESP-related miracles preparing either side of the Iron Curtain for what was to happen, though plenty of other experts in numerous fields made their own predictions relating to what was happening, and what was next. It’s hard to point to anyone who predicted what actually happened.

With the fall of the Soviet Union came a disappearance of the imminent threat of global war at the time. This led to the shutting down of many strategic military research projects and changes in defense spending on both sides. In the Soviet Union, most of the research and development of the newest types of armaments, including psychotronic weapons, was discontinued. People who had been trying to develop psychotronic generators or information transfer equipment began thinking about civilian applications for these inventions, primarily in the medical and ecological spheres. However, stories about collaboration between Russian Special Security Services and the military on the psychic front continue.

Included in the US program closures was Star Gate. More of the story of its closure, the politics around that, and what was next for some of the principals involved is the subject of this chapter. Star Gate’s last director Edwin May provides us with the “death throes” of the program, which lasted several years after the fall, and ended in 1995. Joseph McMoneagle tells the story from his perspective.

How the program came to be known to the public and scientific community, the fallout from that, and the closure is itself quite a commentary on how the ESP Wars were bound up in politics and scientific prejudices.

Edwin C. May

Many people are unaware that the program suffered an earlier closure, which led to the shift from SRI to SAIC. “In 1989-90, for the nine months following the closing of our program at SRI,” began May, “I was basically

unemployed. During this time, I was in full marketing mode. I would call my Senate Staffer contact and lie to him by saying that I was going to be in Washington on other business, and would he and his Senator boss have 1/2 hour or so to meet with me?” On those occasions when he got a yes, May would scramble to make all the flight, car, and hotel arrangements so that he could make the meeting in Washington. “I am not sure how many visits I made during this time, but I spent probably close to $20,000 of my own money for travel expenses.”

This practice was “sort of” successful. Looking for six million dollars, “what made it through the appropriation committees and the House/Senate conference committees was only two million.” However, this was only the beginning of the problems that arose. “Congress can increase the budget for some Executive Branch agency, which in turn can provide a contract to individuals or corporations, but they can’t do it directly.” May and the project had two major problems: no receiving company for the future contract, and, at the time, no agency to do the contracting with the freshly appropriated funds.

“I hit the road again, trying to solve the contractor problem,” said Ed. His wanderings took him to some of the top defense contractors. Many of their CEOs strongly supported the concept, but at the end of the day, they opted out. “I was getting a little desperate so I called a former Air Force client friend of mine, Colonel Joseph Angelo (now retired from the Air Force) to seek his advice. After all, I did have a virtual suitcase full of a virtual $2M in cash! That should stand for something, I thought.” Lucky for May he’d guessed right. Col. Angelo had loved the work and asked, “When and where do you want your office with Science Applications International Corporation,” the company where he was working at the time.

The project was almost set for a new home, though Col. Angelo told Ed that he would have to convince Angelo’s boss of the worthiness of the potential new program. A meeting was set up for a few weeks later at SAIC headquarters in San Diego between May and Angelo’s boss, Tom (name omitted for privacy).

They met and, after some pleasantries, moved to a conference room where May asked Tom what Joe Angelo had told him about the briefing. “Joe said that he respected your work and you were a physicist,” Tom said.

“Is that all?” May asked.

“Yep,” he replied.

May was ready to cancel the meeting, fly to Florida, and “choke Joe with may bare hands! How could he NOT tell his boss that I was going to talk about ESP? For all that Tom knew at that moment was that maybe I was going to speak about some nifty new over-the-horizon radar or some other physics intelligence gadget.

”

May recalled that he swallowed hard and waded into uncharted waters.” Five hours or so later Tom was asking me for a job. He was riveted on the idea. Thus the government-sponsored ESP program had an industrial home, and a very good one at that.”

There was still the other bigger problem, the question of which agency would take responsibility for the contract. Given the SRI Program history with the Defense Intelligence Agency, it seemed a natural fit, but the 3-star General in charge flatly refused the program. “That started a war with the Senate which, by definition, the Senate wins,” said Ed. “I was shown a formal letter addressed to that recalcitrant 3-star commander from the senior member of the Senate Select Committee for Intelligence, who had visited me earlier at SRI, informing him that he had 24 hours to show why he was not in formal contempt of Congress by refusing this program. Let me assure you, this is not a happy letter to get from Congress to further one’s career.” The letter worked its own “magic” and the new program ended up at SAIC with the contract coming from DIA.

What does all this have to do with the eventual closing of Star Gate? “Plenty. Naively, most people think that the military chain of command rules the day,” said May. “Generals tell Colonels who tell Majors who tell Lieutenants what to do. Well not exactly. Most often senior officers respect the judgments of many of their junior officers and professional staff and rarely overrule them. At times when this is violated, the so-called letter of the law is followed, but often not the intent. There was a well-known example of this during the Carter administration. The President had a scientific interest in UFOs and dropped in on NASA to ask the director to look into this phenomenon. The director said, ‘Yes Sir!’ the President left, and NOTHING further happened.”

In 1990, the 3-star commander of the DIA followed the Congressional wishes but only to the exact specifications of the request. “For the next four years DIA did everything they could to create road blocks to make it as difficult as possible for the program to flourish or for that matter even survive. With one exception, the DIA brass assigned total career-ended incompetent people to run the Ft. Meade remote viewing program. Morale plummeted within the unit. So much so, in fact, that on many of my frequent visits to Ft. Meade, different staff members of the unit would take me to lunch and beg me to intervene on their behalf. I did so but with absolutely no effect whatsoever. The word had come down from the top: Make the program vanish.”

On the plus side, the SAIC portion of the program prospered for a bit more than four years and produced a number of peer-reviewed publications. Like during the previous incarnation of the program at SRI, they had a Scientific Oversight Committee to assure their sponsors that they were doing the best possible science, an Institutional Review Board to assure the ethical use of

human subjects in the experiments, and a Policy Oversight Committee to assure that the work remained in compliance with the Department of Defense’s overall mission.

As the geopolitical climate began to shift with the ending of the Cold War, their funding began to run out, with the intelligence requirements slowly shifting from mostly strategic to mostly tactical. Ed May provides an example. “Let’s say there was a site in the Soviet Union that we were watching for some time and wished to know what was happening at that moment. Tactical intelligence is more concerned with the immediate circumstances, such as ‘tell us where the downed aircraft is in the next hour or so.’ Strategic intelligence is concerned in the long term.” In addition the political support and cover for the program also waned. Finally SAIC slowly began to pull the plug.

Word came to May from his management that they had to reduce staff and give up their functional and comfortable offices in Menlo Park, California, and move a skeleton crew to an existing San Francisco office of SAIC. For May, that meant a 20 minute walk to work turned into a difficult hour or so by train and bus commute. More importantly, however, was the shift in emphasis from research to cleaning up the contractual loose ends and to start a storage and archival activity. Fortunately, most of the staff found other jobs, and the close bond they shared on the job survives through to today even though they have all scattered across the globe.

Finally SAIC asked May to move once again for a brief period to an SAIC office in Palo Alto. The good news was that he could ride his bike to work; the bad news was this was the end. His main role was to box up reports and declassify others. “However, in parallel to all this moving, I was given a small mandate to support a Central Intelligence Agency’s program review.”

The terrible situation of the Senate Select Committee for Intelligence having to cram the program down the throat of the DIA—a win that wasn’t—was recognized by one of the Staffers for Senate Appropriations Committee. He decided to take the program away from the DIA. His mechanism of choice is called a Congressionally Directed Activity (CDA), which was part of the Department of Defense’s Appropriations fiscal year 1996 bill. The CDA asked the Central Intelligence Agency to conduct a retrospective review of the 20-year ESP program to determine its overall efficacy as a tool for intelligence collection. Moreover, if the CIA found that the program had merit, the CDA ordered them to assume responsibility for the program including transferring all the associated DIA personnel to CIA.

In compliance with the CDA, the CIA let a small contract to May via SAIC to assist, as needed, in their evaluation by supplying requested documents. “That I did and acquired a tan from the copy machine with all the reproduction I was asked to do!” said Ed. Initially, he was excited to work with Dr. Andrew

Kirby, a physical chemist working for the Science and Technology directorate of CIA. At the start, Andy was not knowledgeable about the topic but “his enthusiasm was refreshing given the gloom of the DIA people for the last few years.”

However, it slowly dawned on May that something was amiss. The earlier incarnations of the Star Gate program had more oversight within the Department of Defense including from the office of the Secretary of Defense, than perhaps any other current program. These reviews had been ongoing since 1985, but there were also some dating from the earliest days of the program. The program passed muster with regard to the Department of Defense’s mission, the science and methodologies of the contractors (SRI and SAIC), and it had met all guidelines for the ethical treatment of humans in experiments.

“So I thought that CIA’s internal review would have a substantial leg up given the myriad of published government reviews—the CIA could begin where these had left off.” Unfortunately, Kirby told May that the Agency would only look at the results of the last few years, which included the period of the terrible morale mentioned previously. Furthermore, the Agency contracted out to the American Institutes for Research (AIR) to conduct that limited review. “At first look, AIR’s approach looked reasonable. They assembled a team of experts who had open minds on the topic. But sadly the fix was in!”

Three Ph.Ds—Michael Mumford, Andrew Rose, and David Goslin—prepared the report for AIR on the Star Gate program. This report was based on the expert evaluation of Professors Jessica Utts (dubbed as representing the pro-psi group) and Ray Hyman (considered a skeptic). The tasking for the reviewers was to cover four general areas:

Was there a statistically significant effect?

Could the observed effect, if any, be attributed to a paranormal phenomenon?

What mechanisms, if any, might plausibly be used to account for any significant effects and what boundary conditions influence these effects?

What would the findings obtained in these studies indicate about the characteristics and potential applications of information obtained through the remote viewing process?

As Mumford, Rose and Goslin (p.3-80) report:

One of Dr. Hyman’s first comments about Dr. Utts’ review was that he considered it perhaps the best defense of parapsychological research he had come across. We concur; likewise, we feel that Dr.

Hyman’s paper represents one of the clearest expressions of the skeptic position we have seen.

At the outset, it should be noted that the two reviewers agreed far more than they disagreed. One central point of agreement concerns the existence of a statistically significant effect: Both reviewers note that the evidence accrued to date in the experimental laboratory studies of remote viewing indicate that a statistically significant effect has been obtained. Likewise, they agree that the current (e.g., post-NRC review) experimental procedures contain significant improvements in methodology and experimental control.”

Their technical paper can be downloaded from www.lfr.org/LFR/csl/library/AirReport.pdf.

AIR’s September 1995 final report was released to the public two months later, and according to May, “the bottom line was nearly schizophrenic.” As a result of AIR’s assessment, the CIA concluded that a statistically significant effect had been demonstrated in the laboratory, but that there was no case in which ESP had provided data that had ever been used to guide intelligence operations. The conclusion was that ESP was not useful for the intelligence community—in direct opposition to a substantial number of Department of Defense documented investigations to the contrary. Classified and unclassified versions of the report were written and presented to Congress in compliance with the CDA. “Oddly I was denied access to this report—even the unclassified version. Some of the authors of the report were allowed to review the material and add comments or in some cases submit complete papers in the form of a rebuttal to other sections of the report—a minority opinion so to speak.” May went to Washington to visit the Senate Staffer who wrote the CDA and complained that he had not been allowed to see the report on the program of which he was the contractor director. The staffer gave May his own copy.

Reviewing the report, there are some interesting highlights. Jessica Utts, a professor of statistics at the University of California at Irvine, and formerly at Davis, stated as part of her analysis:

Using the standards applied to any other area of science, it is concluded that psychic functioning has been well established. The results of the studies examined are far beyond what is expected by chance. Arguments that these results could be due to methodological flaws in the experiments are soundly refuted. Effects of similar magnitude to those found in government-sponsored research at SRI and SAIC have been replicated at a number of laboratories across the world. Such consistency cannot be readily explained by claims of flaws or fraud

.

T

he second expert reviewer, Ray Hyman, a professor of Psychology at the University of Oregon, while agreeing on the statistical evidence, felt that competing explanations for the phenomena have not been eliminated, a viewpoint that is disputed by Utts. However, considering these are still relatively early days in the investigation of psi phenomena, and there is a growing body of research from other groups and laboratories, in the spirit of science and inquiry, we need to continue with this investigation and attempt to address the most vital question, the how of psi.

There are also a host of technical reviews of the experimental literature on parapsychology, known as meta-analyses, which merge together most of the available published research directed toward a particular topic. Utts published one such review paper in the prestigious statistics journal Statistical Sciences, and psychology professor Daryl Bem from Cornell University, along with the late Charles Honorton, published a notable review of the literature in Psychological Bulletin investigating a type of ESP research methodology known as the Ganzfeld—a procedure where psi is observed when the participant is in a mildly altered state of consciousness. Furthermore, since the publication of the AIR report on the Star Gate program, scientists have continued evidentiary and explanatory studies using improved methods and technology, the results of which cannot be dismissed outright.

Although doubts have also been raised against the utility value for military purpose, it is important to note that many eminent scientists, including academicians and Nobel laureates, supported these programs. Prominent scientists have been involved in the exploration of these phenomena from the early days of its experimental investigation in the late 19th

century. While officials of the American government involved in the Star Gate program may be reluctant to “come in from the cold,” once again it’s fair to mention that McMoneagle’s Legion of Merit award is evidence of their support and satisfaction with the applied aspect of the program. Needless to say this acknowledgement does not support the doubts raised by the reviewers of the program on the value of psychic espionage as one of the methods of intelligence gathering.

A copy of the AIR report was leaked to the US press and media before its official release. “At this time I was still a paid employee of SAIC, and I went to my management to inform them that that there would be a public release attesting to the fact that the US Military and Intelligence communities had supported ESP research and that SAIC had been one of the contractors.” May’s boss asked him to keep him informed especially because SAIC’s corporate culture at the time included complete media avoidance. By this time they had physically closed the program doors at SAIC’s Palo Alto office and

May was placed on administrative leave without pay, but his medical insurance was kept in place and his security clearances were kept active.

“I told my boss, who by the way was always supportive of our program, that I had received a call from the American Broadcasting Company’s news division and was cooperating with them. I told him it was extremely likely that I would be asked to appear on a popular late-night news magazine show called Nightline with Ted Koppel. I received a go-ahead nod from my boss, but clearly this put him and the company in some immediate stress.”

It happened, and May was invited to go on Nightline opposite former CIA director Robert Gates (who later served as Secretary of Defense) and a CIA analyst who was described only by his first name, Norm.

“Again, I informed my boss that this was happening and told him the scheduled date and time of the program.” Unlike most of the other Nightline shows, which were always broadcast live, this one was being taped a few hours in advance of the air time. A few hours before he was scheduled to drive to an ABC studio in San Francisco for the taping, Ed May received a most difficult call from his boss.

“Ed, you are on speaker phone with my management and SAIC corporate lawyers. We order you NOT to go on the Nightline show.”

Ed actually thought he was kidding given their very friendly relationship and mutual respect. As a result, he promptly made the first of a number of mistakes during this life changing—at least for May—phone call. “Why are you saying this?” Ed asked.

“Well, we are all concerned that you will reveal classified information.”

“My response was mistake number one. ‘Look,’ I said, ‘I’ve been working in classified environments since I was 20 years old in 1960, and if I were going to reveal classified information, I would not do it on some TV show; rather, I would sell it to the Russians for a huge bunch of cash.’ I thought this was a funny joke. WRONG. Dead silence followed my wise crack.” In a flash, May realized he had just stepped in it and had better stop joking around.

Finally, after what seemed an eternity, his boss said in a very somber voice, that now they were afraid that he would reveal SAIC company propriety information. He responded with purposeful intent that he had “been invited on the show simply to keep Director Gates honest in that he knew, and that he also knew that I knew that he knew, that our program was useful to the intelligence community. Moreover, I was only going to speak of research issues that could be found in the journals in the library and, as part of my agreement with ABC, I would not mention, nor would they, SAIC’s involvement.” They had reached an impasse. Clearly SAIC was not going to back down and May was faced with a terrible choice, which he did not handle well. “On the one hand, this show was one of the media’s top venues and this

would be the first public extensive exposure ever of the formerly classified program—how could I not do this? Yet, even though I was on unpaid administrative leave from SAIC, I did not wish to burn any bridges to a company I admired and to a boss I liked and respected.”

“In retrospect, even now, close to two decades later, it is difficult to tell if I made the right decision. Instead of entering into a negotiation to ascertain about what they would give in return for me not going on the show, I told them that my resignation letter would be on their desks within the hour.”

So they knew that May was going on the show and they could not stop him. “What happened next was both frightening and terribly disappointing. In effect, I was directly threatened that both the CIA and SAIC lawyers were going to watch the show carefully. Now in a shaky voice but reverting back to my ‘humorous’ approach, I wished them well and hoped they will enjoy the show, perhaps they should get some popcorn.”

Sadly for Ed May, that severed his relationship with his boss, “a most competent scientist, a supportive manager, and all around delightful man,” said May.

After hanging up the phone, Ed told his wife Dianne about the conversation, “and she was as shaken as I. What to do? I was determined to go forward with the show, but she did not want me to.”

They contacted Dianne’s ex-husband, a competent lawyer, seeking advice. “Don’t do it,” he said, “it’s too risky on a number of legal and personal dimensions.”

Nonetheless, in the face of all this personal and legal advice, May did the interview, the transcript and video of which is still available online from a few sources. As it turned out, all the angst was unjustified. However, while there were no legal consequences, May’s private research life via government contract came to an immediate and seemingly permanent end.

A multi-year and mostly unpleasant media feeding frenzy followed the Nightline exposure. Just as this began, on one of May’s many visits to the senior Senator on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence who started the SAIC era of the program with his visit to SRI back in 1989, he was asked if he could rebut the AIR report. “I told him that it would be embarrassingly simple.” He told Ed to do it and pull no punches. May’s report, which is a scathing review of the CIA’s methodologies, demonstrated beyond a doubt that the CIA had determined the result of their investigation before they actually conducted the study. “I think my subsequent paper is another example of winning a battle but losing the war. Sure it was easy and great fun to ridicule the CIA and their methods, but I think that had long-term consequences that may exist through to today.” That published report can be found at www.lfr.org/LFR/csl/library/AirReview.pd

f

M

ay provides us with a summary that points out the technical and administrative reasons why the Star Gate program closed. First the technical:

The intelligence mission shifted from mostly strategic to mostly tactical. This shift sharply lessened the efficacy of ESP intelligence collection.

The research did not solve a very pressing problem. How do we know, in advance, if an ESP-generated intelligence report should be taken seriously enough, in totality or in part, to justify taking any action? Director Gates said on Nightline that no action was taken on the bases of ESP intelligence alone. He was right and my remarks were edited out of the show. “Mr. Director, you are correct, but it is also true that one should never take action on the bases of a sole source.” Yet in a related problem, we never did develop a protocol about how to integrate ESP intelligence data into the general intelligence community.

Unfortunately, the general level of ESP performance is not as good as it is often described in public venues. The scientifically certified performance could not and did not live up to these expectations.

Aside from these technical difficulties, which perhaps could be solved in some later program, the administrative reasons for the closure of the program were nearly insurmountable. These included:

The Congressionally Directed Activity order to the CIA to accept the program including all of its current personnel given that they found it to be useful. “In my view, this placed a significant burden upon CIA. In general, a shift in program means a fresh start and I think no one would want to be saddled with potential problems associated with a previous administration of such a program.”

Contrary to public impression, the Star Gate program survived only in part because of its intelligence and scientific successes. For its 20-year lifetime, the program was always in the cross hairs of one group or another in trying to close it down regardless of its merits. “The principle reason it survived, then, was because of the significant courage exhibited by a very few senior government people who, in some cases, put their own careers on the line to keep Star Gate in place. By the time of the AIR retrospective review, most of these remarkable individuals had either retired, or in some other way moved on. In short, we lost our political cover.”

During this sensitive time, a few well-meaning, but ill-informed, government project personnel thought they were trying to save the program, but their enthusiasm was taken, correctly so, as serious exaggerations of the capacity of ESP-derived intelligence. “In short, through the life of 20-year program, we were often hurt more by the support of our ‘friends’ than any of our critics!

”

T

here were other person-centric issues that both helped along the demise of the program and prevented it from being picked up again by any other department or office. One involved an inter-office “entanglement.”

In business, managers at all levels have to deal with a problem: romantic (or just plain sexual) relationships that interfere with the structure or workings of the business, especially between managers and subordinates. Often these liaisons lead to destructive consequences for the organization, and at the end of the day, no one wins: not the man (married or not), the woman (married or not), nor the organization. The military is not exempt from this general societal problem.

Neither was the Star Gate program. A very powerful government official (unmarried) began dating one of the women (unmarried) way down the “food chain” within the heart of the program. Sadly—though predictably—this caused a major managerial problem.

During the final days of the project, May had developed a close working relationship with the aforementioned Dr. Andrew Kirby at the Science and Technology Division at CIA, but now a senior physical scientist at CIA’s Intelligence Technology and Innovation Center. As mentioned, he had been assigned to head the CIA’s internal investigation of Star Gate, in accordance with the Congressionally Directed Activity. Kirby was initially quite neutral with regard to matters psi, but as is often the way with honest scientists, he became fascinated with it, and his relationship with May warmed. So much was his fascination that he had planned to attend, as a CIA scientist, the 1995 Parapsychological Association1

(PA) annual conference being held in Durham, NC that year.

As part of a lengthy phone conversation May had with Kirby, Ed informed him of this difficult romantic liaison. Ed also said that should the CIA take the program as directed and include all the Star Gate personnel, they would be in for major problems. Furthermore, Ed suggested that Kirby not believe a word of what he said but verify, or not, his contention. Kirby thanked Ed and hung up.

About a week later, May received a most distressing call from Andy Kirby. “He said ‘Ed you have grossly underestimated the extent of the problem. A decision has been made at a much higher pay grade than mine, so I cannot ever speak to you again.’ He abruptly hung up the phone, and to this day nearly 20 years later I have not heard from him,” said May.

This romantic entanglement certainly did not cause the closing of Star Gate, but equally certain it was a contributing factor.

Another individual-driven issue came up when May and Joe McMoneagle found themselves caught in a sort of character crossfire

.

Long after Star Gate had closed, Joe and Ed spent considerable time and money in trying to get various arms of the military intelligence community interested in starting something up again at a very low level of activity and very classified.

In part, the motivation for this was the apparent lack of interest of the DIA upper management. In 2000, with Russian General Alexei Savin’s blessing, May and McMoneagle wrote what is called in the business a “contact report.” In this lengthy report, they described in detail their meeting with the Russian version of the Star Gate program, Military Group 10003. In addition, they provided photographs of the principals involved and an outline of an organization chart displaying how exactly the Russian program fit into the larger picture in Russia. Moreover, the report was explicit in Savin’s request for a joint effort to address the common problem of terrorism for both countries. May handed a copy of this report directly to the three-star commander of DIA at the time. It appeared to be good timing, as that commander was scheduled to travel to Russia to explore joint operations with his counterparts. This seemed like a natural for the psi people. For some reason, however, nothing ever came of this.

McMoneagle and May ran into this same problem for seven or eight more years. That is, at the working level, the people were vitally interested and willing to offer monetary and other support. Yet any new effort that involved psi was killed in the “board room” that is upper management in the military.

There was one exception to this. One of Joe’s military colleagues and friend (who must remain nameless here) invited Joe and Ed to come to a base in Hawaii for a week to write a proposal for further work. They were offered $10,000 for the job plus expenses. So, off they went for a week on Oahu.

Upon arrival, they briefed the appropriate “brass” on the project, who turned out to be a senior female officer in charge of intelligence. They were given the go-ahead to write a proposal, but the requested funding was to be limited to only $200k—very small in terms of military budgets. A week later, they had prepared a proposal that fixed many management and expectation errors of the operational side of Star Gate, set unmovable goal posts to define success, and provided many exit points on which to cancel the project should the on-going tests not work. During their exit briefing to the officer, she asked if they could provide political cover in the Pentagon for this obviously controversial program. May said he would check.

May scheduled an appointment with a former colleague from the Senate Select Committee for Intelligence who by then had a civilian job with many high-level ties to the management within the Pentagon at that time. “Through this man’s effort,” said Ed, “we obtained the blessing to move ahead by one of the few Assistant Secretaries of Defense—mission accomplished.

”

Two weeks or so later, May received a phone call from the comptroller for the Pentagon saying he was ready to fax the statement of work and move ahead with the contract. Ed told him he no longer had a classified fax machine. To which the comptroller replied, “Not to worry, the effort is unclassified.”

At this point May admits he made one of his most devastating mistakes of his career. Instead of calling his Pentagon contact and inquiring what was up (with the project not being classified), he contacted the female senior intelligence officer in Hawaii. “She was overjoyed that I had saved her ‘six’—which is military jargon for one’s behind. For obvious reasons, it would have been both genuinely dangerous for the project’s participants, as well as open the military for media ridicule should word of it have gotten out at that time.” She cancelled the request to the Pentagon.

“That action caused the proverbial shit to hit the fan,” said Ed. “I received an angry phone call from my friend and Pentagon contact saying that I had substantially hurt his business and the reputation he was building. That rift took many years to repair.”

May and McMoneagle found out later that the Assistant Secretary of Defense had it in for that “uppity female” intelligence officer and was going to use their program to embarrass her. He knew full well that the program should be classified but also knew that unclassified, it would be only days before it would be a major news story.

Ed commented that, “We never did see the promised $10,000, and it took years to finally be reimbursed for an expensive week on Oahu.”

May concluded his account with, “As far as I know, and I think I would know, the US Government has had no formal program to use ESP to help with the intelligence gathering in our troubled world since they closed down the Star Gate program in September, 1995.”

R

egarding Edwin May’s recollections, it is important to emphasize that, although it may seem as though Star Gate was shut down due to bureaucracy and internal politics, interest from government institutions such as the Department of Defense, the CIA, and the DIA was also waning at the time.

Could Star Gate have survived? Yes, but only in a different form, working on current problems such as terrorism, organized crime, locating missing persons, and so on–just as the Russians were doing internally. Naturally, this would have required international cooperation, and the American bureaucracy was clearly not ready for this shift in thinking. It also would have required

interpersonal issues, like the ones mentioned above, to remain at a minimum (or better still, non-existence).

The former Star Gate program participants were indeed prepared to move forward with the research, and made attempts to get the project going again in different forms. Ed May visited Russia many times in the 1990s. In 2000, he offered his program colleague Joseph McMoneagle the opportunity to come along on one of the trips. For Joe, who as an intelligence officer had been involved in espionage targeting the Soviet Union, this offer caused conflicting feelings. On the one hand, Joe had never visited Russia, and it was interesting for him to look at a country with which such a large part of his career had been involved, and to witness the changes occurring there. On the other hand, the image of enemy was still not fully erased from his picture of Russia. Therefore, his attitude to the trip was ambiguous.

But Joe, along with Ed, was capable of altering that image and of rejecting the stereotypes that had dominated the relationship between the USA and Russia for so long, though this did not prevent him from being critical of the residual Soviet mentality. In the following section, we present Joseph McMoneagle’s story about this trip and his meetings with his Russian colleagues—military men and intelligence agents who had once been his opponents, but who by now had become his friends.

Joe McMoneagle

In October 2000, Ed May asked Joe McMoneagle if he felt up to a trip to Russia. May had obtained sufficient funding for them to travel to Moscow and was confident that they would be able to arrange a possible meeting with some of the major players from the Russian military ESP program. It was just over ten years since Perestroika and, while there were some very major changes taking place under the Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev, there weren’t many changes with the people’s way of thinking and doing things. “So, I was both very interested and also somewhat nervous about the trip,” said Joe. “This was my point of view as a retired Army officer, whose job in the past was to spy on the Soviets.”

Immediately, it was clear that the old Soviet way of thinking and doing things still persisted. In order to obtain a visa for the trip, Ed had gotten an official invitation from General Alexei Savin. But since the official copy of this invitation was being held by the Russian Counsel on the West Coast where May was located, it required communications between him and the Russian Embassy in Washington DC where Joe needed to pick up his visa. “My trip into Washington to obtain the visa quickly expanded from a simple matter of a one hour visit to the Russian Embassy to two days of bureaucratic nightmare,” said Joe. “While they acknowledged that the official request

existed (albeit on the West Coast), they couldn’t seem to find anyone within the embassy authorized to issue the visa without an actual copy of the invitation being held there.” This required forwarding the invitation electronically from the West Coast to the East Coast, a process that took almost 48-hours.Eventually, they called McMoneagle’s hotel and informed him that he could pick it up on the second day, less than 72 hours from his actual departure from JFK in New York. Joe and Ed had agreed to meet at the airport in London where they were scheduled to fly out to Moscow together. May had the itinerary in his possession, as well as hotel reservations, and other necessities they needed for their trip.

Unfortunately, Ed never made it to the rendezvous in London. “I checked on his arrival time and knew that his plane had landed, and he was probably on the ground somewhere,” said Joe, “but he couldn’t get through customs in time to catch the flight to Moscow. I stood at the boarding door until the senior flight attendant told me that she was shutting the door and, if I wasn’t on the other side of it, the plane would be leaving without me. I reluctantly boarded, knowing that I was headed to Moscow, with only the name of the hotel in my pocket and a foolish inability to even ask where a toilet was in Russian. Our colleague and translator, Larissa Vilenskaya was already in Moscow and we were supposed to meet there.”

On Joe’s arrival in Moscow and clearing customs at Sheremetyevo International Airport, he retrieved his baggage and caught a cab to the hotel, finding a cab driver who could read the English name for the hotel. “Ed had made reservations for the Marriott Hotel because, as an American hotel chain, it supposedly met Western standards. Unfortunately, they had not yet been able to accustom their employees to operating it as a Western hotel is normally run.” Joe’s attempt to check in resulted in some major complications as Ed had made the reservations for the suite, and had put the reservations on his credit card. “They wouldn’t let me check in because I wasn’t Edwin May. After about an hour of arguing with the manager they agreed to give me the room, but only if I transferred the charges from his credit card to my own. Fortunately, we were able to eventually straighten out the situation, since back in those days the costs were so high, it nearly wiped my card limit clean.”

This caused a bit more in this comedy of errors. When Ed arrived after catching a later flight, the hotel wouldn’t honor his reservation because he no longer had one—it having been transferred to Joe—and they wouldn’t let him up to the room because it was under Joe’s name. Eventually they called McMoneagle down to the lobby and they were able to straighten it out at least temporarily. “During the entire two week stay, we were required to report to the front desk every morning to trade our old electronic room keys in for new ones because the codes wouldn’t operate on the doors for longer than a 24-hour period. Eventually, Ed and I were able to sit and have a long conversation

with the very pleasant Concierge, who was trying very hard to please everyone, and some changes to their rule book were made.”

It took some time to arrange the official meeting, so Ed and Joe spent a few days relaxing and visiting some of the general areas of Moscow. This was very exciting for Joe because “up until the trip the only thing I knew about Moscow was what I had seen in training films, or bits and pieces I’d gotten in briefings about the old USSR. There were a number of things that struck me as being both interesting and strange. While visiting Lenin’s Tomb, on exiting I noticed that directly across Red Square from the tomb entrance sat a huge department store—GUM. The interior of GUM had been completely changed from the way it used to be under the rule of Communism. It now contained hundreds of shops carrying the very latest in fashion from around the world. It was well lit and as beautiful a shopping mall as you would find anywhere in the United States. I wondered what Lenin would think about that were he able to suddenly sit up and see it.”

Just down the street a ways, there was an even better shopping mall just off Red Square, constructed almost totally underground. Three floors of shops, containing everything and anything one might need. New restaurants were everywhere, including a three story McDonald’s with seating for 500 people. “It was evident that the Russian people were already thoroughly enjoying the significant changes taking place within their capital city. If you looked closely though, you could see that it was still in that difficult process of change.”

While they waited, Ed and Joe were invited by Professor I. M. Kogan to give their standard presentation on remote viewing at the famous Moscow State University, which had a significant number of people in attendance. Joe noticed there were a number of military officials at the rear of the presentation area during their delivery. They fielded a lot of questions during the presentation, “including the one we’ve never been able to answer—how does remote viewing actually work?”

The day finally came when a black Mercedes arrived mid-morning at the hotel with driver and escort to take them to their official meeting. “Ed and Larissa didn’t look nervous, but I was. I was finally going to get to meet the people who were my counterparts for so many years during the cold war.”

They drove for some time to the outskirts of Moscow. Once leaving the major urban center, they entered an area, which would have to be called rural, eventually leaving the paved track of road and entering a gravel roadbed not unlike the road that leads to Joe’s home in central Virginia. It took the better part of an hour to get to the destination, which was a very modern looking dacha (essentially something on the order of a summer home) with a wall constructed of wood around it. The gates opened and they pulled inside and parked. Waiting at the door was Lt. General Savin and Security Service

General Boris Ratnikov, along with a woman security officer and numerous others. “They greeted us warmly and took us inside and gave us a tour of the facility. It was clear to me that this was possibly one of a number of meeting places they might maintain, this one being one of the more recent ones constructed. There were facilities for meditation and study, as well as a briefing room, which probably was also used as a school room. There were offices and a general lounge area with kitchen facilities. Attached to the main building they had underground lab facilities, as well as computer facilities, and even a rest and recreation area that included a wet sauna. It was far and away better than anyplace I had ever done remote viewing.”

After the tour, they were formally introduced to the Russian psychics who were present. Most were much younger than Joe. They had what appeared to be the same approximate mix of male and female that existed within the Star Gate unit. “I was introduced to their Number One viewer, a woman named Elena Klimova, who I sensed was probably about as nervous meeting me as I was her. We later learned that she had earned a high Russian decoration for her psychic functioning during the Chechnya War, working from a front line, main battle tank. I suddenly felt like a wimp.”

After introductions, they retired to the classroom where they received a lengthy briefing on what the Russians were doing in their work. “At this point, I must confess that I took a lot of notes. The Russian culture is somewhat different from the typical American’s. So, there were a lot of things in the psychotronic area which I was not familiar with but which they seem to have an exceptional and long-lived background in. I spent more time listening than speaking or asking questions.”

After a number of hours, they broke for refreshments and moved to the lounge and kitchen area. “In the course of my years in the Army, I traveled extensively, and socialized with numerous cultures all over the world. In the course of that socializing, I’ve probably drunk enough to float a battleship. But, I have to say that of all the celebratory social gatherings I’ve ever attended, the Russian military really know how to throw a party.” The table was piled with food and bread from end-to-end and everyone sat around the table, as one would within a family dining room. As soon as McMoneagle began eating, someone handed him “what I would call a small juice glass in America. They filled it with vodka and once everyone’s glass was full, someone stood up and made a formal toast that was exceedingly nice and which went on for some minutes, at the end everyone downed the vodka and slammed their empty glasses onto the table. I realized by the time I had downed three glasses of vodka, they were working their way around the table, eventually reaching me.” Joe stood at attention and held his glass high–“and hopefully straight—and gave a toast from my heart. I honestly can’t remember exactly what I said at the time because Vodka does that to you, but whatever it

was, it must have been the right thing. I got a bear hug from both sides.” After the party, they returned to the hotel where Joe promptly spent the next 15 hours recovering.

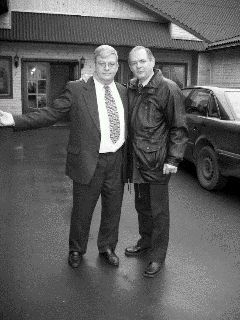

Joe and Elena just after their joint RV session.

They returned to the facility the next day. There were more briefings, and Joe was able to participate in an experiment with the Russian’s top female psychic, Elena Klimova. Completely isolated in a totally darkened underground chamber, Joe was asked to draw whatever came into his mind that she might be drawing. He was told that the starting signal would be a bell that he would hear through headsets. Klimova was in another part of the facility doing exactly the same thing under the same conditions.

“It is very disorienting to sit quietly in a totally black room, where you can’t hear anything, for a period of approximately 30 minutes, and then have to draw on a digitizer pad with an electronic pen something that you can’t see. But, that is what the task was and I decided to give it my best shot.” He heard a bell in his earphones and decided that he would simply “let her guide my hand remotely on the digitizer board.” When the second set of bells rang, the task was ended and Joe was taken back to the office area. They made a comparison of what the two had drawn. “The drawings were almost perfect mirror images of one another. I think everyone in the room was greatly surprised.”

During the last few hours of that second visit, Joe asked if it would be possible to take photographs. This initially caused some degree of anxiety with the security officer, but after discussing it with General Savin they were given permission with the provision that we wouldn’t publish the photos until given official permission to do so. “We agreed. These are now being shown for the first time within this book.”

Joe McMoneagle and General Alexei Savin

Before they left Moscow, General Savin made arrangements for Ed, Larissa and Joe to tour the Military Veterans Hospital on the outskirts of Moscow. The Commander of the Hospital took time out from his busy schedule and gave the three an extended tour of his facility, which he was very proud of. “I cannot blame him for being proud. Back in those days, the New Russian government didn’t have a great deal of money, and maintaining the facility was a tremendous difficulty. One could readily see that there were improvements that could be made to the buildings and interiors. However, the entire hospital was very clean and well maintained to the extent it could be.”

What impressed Joe the most was the approach they had in the care of their wounded. Active duty veterans who were in the hospital were not being rehabilitated for discharge into the civilian work force. They were being rehabilitated for discharge back to their military units. This included limb-amputees. “I spoke with a few of them and they assured me that they would be returning back to their units as soon as they were declared fit enough. They wouldn’t be going back to the same jobs of course, but they would be given jobs fitting their rank and service time that they would be able to handle. They seemed to think that it was better for the unit morale to send the men back after they recovered, rather than force them from the service. That way the country could benefit from their expertise and they wouldn’t become a burden

on the state because they couldn’t obtain a civilian job. I’m sure there were some who would not be able to rehabilitate, however it wouldn’t be as great a percentage as those who were obviously wanting to go back.” In fact, Joe was offered an invitation to return to this hospital as veteran patient any time he wanted and the care would be free of charge.

Joe and Ed played tourist for a number of days and met with other people in the research field, but eventually the visit came to an end and they had to depart. They were told by the concierge at the hotel that the terrible lines and difficulties at the airport could be avoided if they paid a simple charge of only $350 dollars apiece beforehand. They talked it over and decided that it might be worth the effort. For the money, they received a comfortable Mercedes ride from the hotel to the airport at 5 AM. “Our car was stopped three times in route by police, who were obviously checking for something other than us. When we arrived at the airport our luggage went to a side door where we received preferable treatment from our own private customs agent who gave our bags a cursory check and then tagged them through to New York.” They were then escorted to a private bar on the second floor where they had free drinks until another customs official came and took them to the aircraft. They walked down the other side of the glass wall where all the other passengers were waiting to board to the side entry of the aircraft and boarded before the First Class passengers.

“It was a great first trip and one in which I learned a lot about my counterparts, as I’m sure they did about me. It wouldn’t be the last trip and Lt. General Alexei Savin and I would become good friends over time. But by the time we cleared Moscow air space I was again thinking of home.”

Joe McMoneagle flew to Moscow several times and met with his counter-parts, the men and women he worked against for so many years. “We now live in a new remarkable world; some things about it have changed greatly, while others have changed very little. The Cold War ended in what now seems like a long time ago. In visiting Russia,” he continued, “what I found were reflections of myself. Wonderful human beings, thoughtful and insightful, curious and dedicated to exploring the very issues I have spent the past three decades of my life investigating–looking deeply into the shadow world of the human spirit. They are as committed to the protection of their nation as I am to my own, but the difference now is that we share many of the same goals, particularly in the exploration of human consciousness and how it might be used for the good of human kind.”

I

t’s clear from Joseph McMoneagle’s story, and from the accounts of the Russians themselves, that the end of the confrontation of political systems led

to a deeper understanding between the two countries, and set the stage for them to cooperate. However, there were differences still in the opportunities for Russian psychics. By the time of his trip, Joe had already traveled all over the world, presenting the potential of ESP. In fact, for several years Japanese television had broadcast an annual show featuring him locating missing persons. It was so popular that about 30 million viewers watched these shows. Openness to this extent may have seemed quite natural to a retired American psychic agent, but major changes in Russian society had to take place before a psychic who had worked for the Soviet security services would be able to perform in this way.

NOTES

1. The Parapsychological Association is an international professional organization of researchers of parapsychological phenomena. After an impassioned plea by Margaret Mead, it was voted into the American Association for the Advancement of Science as an associate member organization exactly similar the American Physical Society and the American Psychological Association and so forth.