Royal funerals were like no other ceremonial event in seventeenth-century England. They were staged with much more in mind than the simple laying to rest of the deceased sovereign. In one sense, they functioned as displays of power and pomp in the wake of a monarch’s death, visually representing the authority of the monarchy in the grey space between the demise of one royal ruler and the formal accession of the next. But these majestic and dignified occasions were also performed for other reasons: to introduce the emergent figure of the new sovereign, for instance, and to showcase and reinforce social hierarchies through grand funeral processions. Royal funerals were without question designed to dazzle the senses, while at the same time sobering the heart and evoking in a curiously profound way the mournful emotion of melancholy. As continues to be the case today, the funeral of a monarch constituted an important last ritual in the lifecycle of their reign, particularly if it had been a long and prosperous one. It provided an opportunity for people of all ranks, from all backgrounds, to pay their final respects, and to reconcile with the sombre reality that their most high and mighty leader was no more.

Seventeenth-century England witnessed its first royal funeral on 28 April 1603, following the much lamented death of Queen Elizabeth I around two months earlier on 24 March. A surviving relic of her own Golden Age and the wider Tudor faction established by her grandfather, Henry VII, Elizabeth’s death was an especially poignant event because it was viewed by many as the end of an era. As well as being the last of the Tudor monarchs, Elizabeth was able to boast an unusually long reign, her tenure on the English throne spanning some 45 years. She had overseen some significant political successes that had incited celebration on a national scale: the illustrious defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, for example. These various factors rendered her funeral a decidedly important occasion, both in terms of its role as a fitting tribute to a longreigning and successful queen and as a piece of reassuring theatre that filled the gaping void left behind in her absence.

Preparations for the queen’s funeral began in earnest soon after her death, under the instruction of her successor James VI of Scotland – now I of England. Flanked by a sea of burning torches, Elizabeth’s body was first taken from Richmond Palace and carried along the Thames to Whitehall in the quiet closeness of night, the barge transporting her corpse draped in swathes of black cloth. At Whitehall the queen lay in state in a coffin fitted with folds of purple velvet; in this repose she awaited her coming funeral, while at Westminster Abbey black cloth was hung around the west door in anticipation of the arrival of her funeral procession. Meanwhile, fabric for mourning garments was hastily distributed in many thousands of yards to all who were expected to play a part in the day’s events. And there were to be a great many participants. The most spectacular moment of Elizabeth’s funeral was without doubt the magnificent procession that escorted her body to its final resting place within the quiet recesses of Westminster Abbey. The chronicler John Stow remarked of the occasion that, ‘the City of Westminster was surcharged with multitudes of all sorts of people, in the streets, houses, windows, leads and gutters, that came to see the obsequy’. It was an escort in which rank meant everything. At the head of the procession came the Knights Marshals’ men, tasked with clearing the processional route of obstructions and people, followed by 15 poor men and 260 poor women dressed all in black. A little behind marched four trumpeters heralding the approach of the Standard of the Dragon, which was borne by Sir George Bourchier, a Member of the Privy Council of Ireland. Then came the humblest of the queen’s servants, including wine and wheat ‘porters’, bell ringers, and makers of ‘spice-bags’. Another four trumpeters announced the passing of the Standard of the Greyhound, which floated along just behind them, and behind this striking emblem filed more servants of a slightly higher standing than those that had come

before, including ‘herbingers’, tallow chandlers, and brewers.

Further down the procession strode more prominent figures, including ‘Doctors of Physicke’, the queen’s chaplains, barons, bishops, earls, and marquesses, brought up by the Bishop of Chichester, who was to be the preacher at the funeral. The Great Embroidered Banner of England swam majestically through the air after four ‘Sergeants of Armes’, and only a few paces behind appeared in all its sumptuous glory the body of the queen herself, described as:

‘The lively picture of her Highnesse whole body, crowned in her parliament robes, lying on the corps balmed and leaded, covered with velvet, borne on a chariot, drawn by four horses trapt in black velvet.’1

The lively picture of the queen refers to the lifelike effigy, fashioned from wax, which would have been positioned on top of Elizabeth’s actual corpse. The use of wax models in the funeral processions of English royalty was a deep-rooted custom that had been observed since the days of medieval kings, but the practice would lose much of its significance and prominence as the seventeenth century reached its concluding years. The tail end of Elizabeth’s funeral procession was made up of ‘Gentlemen Ushers’ carrying white rods, followed closely by the chief mourner, the Marchioness of Northampton, whose train was carried by two countesses. And so, surrounded by an army of processing mourners of every rank imaginable, Queen Elizabeth I was borne to the Abbey in a regimented sea of black. Proceedings rounded off in a fairly modest way for a spectacle that had been like no other event in living memory. A eulogy was preached by the Bishop of Chichester, who had participated in the funeral procession, and as the coffin disappeared from view beneath the vaulted ceilings of Westminster Abbey, staves were snapped and thrown into the queen’s grave after her corpse.

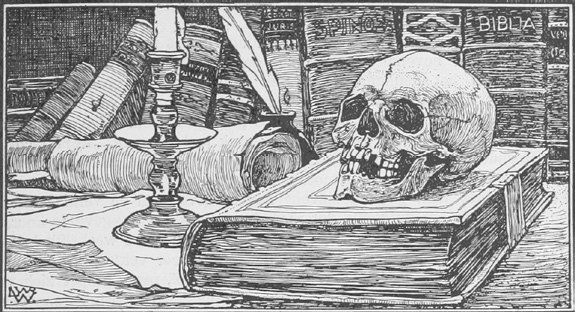

21. A section of the funeral procession of Elizabeth I in 1603, by an unknown artist. Horses swathed in black cloth and decorated with escutcheons pull the hearse bearing the body of the queen to Westminster Abbey. Her funeral effigy can be glimpsed through the collection of heraldic banners held aloft by mourners. Elizabeth’s funeral was a sumptuous spectacle that set the tone for succeeding royal burials in seventeenth-century England.

It was to be little under a decade before the next royal funeral occurred in England, yet this one would be quite different in nature from that of Queen Elizabeth’s. For one thing, it was the funeral of the heir apparent to the throne, the eldest son of James I of the now incumbent House of Stuart, not the funeral of the king himself. For another, it acted as a solemn farewell to a young man who had been tragically cut down in his prime. Elizabeth I had at least lived to a ripe old age, and her passing, although a sad occasion, was not unexpected when it came. The premature death of Prince Henry shook the royal family to its very core. The athletic Prince of Wales began to show signs of illness in October 1612, at the sprightly age of just 18, but he was said to have ignored his symptoms for several weeks before he was finally rendered bedridden at the end of the month. John Chamberlain speculated that a fever concentrated in the prince’s head was to blame, and that his hair had been shaved off and his head applied with newly killed cocks and pigeons in an attempt to save his life. Such treatment was to be inadequate. Henry was dead by the evening of 6 November.

The heartrending circumstances surrounding the occasion ensured that Henry’s funeral would be a tribute on par with that staged for Elizabeth I in 1603. It is estimated that close to 2,000 people walked in the funeral procession of the late prince, including members of his own household and those of the various households of his family. Prince Charles, later King Charles I, was appointed chief mourner, and must have appeared a feeble little character amongst the sprawling pageantry and solemnity of the event, for he was only a 12-year-old boy at the time. Besieging him from all sides would have been the tell-tale markers of a seventeenth-century royal funeral conducted with no expense spared, including banners, trumpeters, horses, and copious numbers of mourners dressed all in black.

Queen Anne of Denmark, Prince Henry’s doting mother, was overcome with grief at the death of her son, so much so that even three years later she could not bear to see her surviving male offspring, Charles, be made Prince of Wales in his place. The queen, suffice to say, was not long for this world. She died early in 1619, probably of dropsy, and so events were duly set in motion to execute another royal sendoff. The planning stages of Anne’s funeral were fraught with difficulties, mainly of a financial nature. John Chamberlain reported on 27 March that money for the ceremony was in short supply, forcing the day of the funeral to be pushed back until the end of April; by the twentyfourth of that month a date had still not been agreed on. Word got out that the proposed funeral was too expensive to pay for, with the event expected to cost at least three times as much as the funeral of the late Queen Elizabeth. Things became so desperate, reported Chamberlain, that there was even talk of melting down Queen Anne’s gold plate and ‘putting it into coin’. Another proposition put forward was to pawn the queen’s jewels and ‘other movables’. Delays were lengthened further by religious tensions, with a handful of Catholic women airing their grievances at being nominated to partake as mourners in a Protestant funeral procession.

In the end, Queen Anne’s funeral was regarded as a decidedly disappointing pageant, barely worth the myriad uncertainties and headaches it had caused in the lead-up to the event. Chamberlain described it as a ‘drawling, tedious sight, more remarkable for number than for any other singularity’. There were the usual ranks of poor women in attendance, numbering 280 in total, and the servants of great lords too, but to Chamberlain every mourner – even the lords and ladies themselves – was dressed alike, and therefore collectively made for a rather ‘poor show’. They came ‘laggering all along, even tired with the length of the way and weight of their clothes, every Lady having twelve yards of broadcloth about her and the Countesses sixteen’. The hearse upon which the body of the queen was carried, however, was described as fair and stately, so there was at least something in the procession to be admired. The solemnities at Westminster Abbey were not completed until 6.00pm, by which time it had been a very long and sombre day. An overall assessment of the funeral, offered by Chamberlain, was that it had gone almost without a hitch, save for the falling masonry en route to the Abbey that had killed a young man.

James I, by now in his mid-fifties and struggling with unreliable health, must surely have been aware as his wife’s body was carried into Westminster Abbey that the next royal corpse to be brought there would in all likelihood be his own. If such a thought did cross his mind, he would regrettably be proven right. James died six years later, on 27 March 1625, leaving the throne to his son and heir apparent, Prince Charles. The king had been suffering from dysentery at the time of his death, and it was this and a stroke that was said to have finished him off, although some suspected murder at the hands of his adulated favourite, the Duke of Buckingham. Whatever the circumstances surrounding the king’s death, another royal funeral was now in prospect, the fourth of any note in 22 years, and it was time once again to begin preparations for a farewell that would eclipse any that had come before it.

James’ body was taken from Theobalds Palace, a favourite country pile, and carried back to London in the intimate darkness of a Monday evening (mirroring the transportation of Elizabeth I’s corpse), through Smithfields, Holborn, Chancery Lane, and the Strand, to Denmark House where it would lie in state until the day of his funeral. Chamberlain remarked that the convoy was ‘well accompanied’ by ‘all the nobility of the town’, including pensioners, officers, household servants, the lord mayor, and some aldermen of the city. The solemnity of the corpse’s initial procession was purportedly blemished by a spell of bad weather, so that through the dark haze blanketing London only the outlines of coaches and the indistinct lights of flickering torches could be observed from afar. The funeral itself took place several weeks later on 7 May, and suffered no such shortcoming. According to the scrupulous Chamberlain, the day succeeded in being a formidable and very visible display of royal power and pomp, as was undeniably its intention. In the letter-writer’s eyes it was the greatest funeral that ‘was ever known in England’. Black garments had been distributed to more than 9,000 mourners, who were to be a part of the by now familiar funeral procession, and the funeral hearse at the centre of proceedings, partly designed by the great architect Inigo Jones, was greatly admired and even considered ‘the fairest and best-fashioned that hath been seen’. Charles was made chief mourner, as he had been for his elder brother in that lamentable year of 1612; he followed the procession on foot, from Denmark House to Westminster Abbey, carefully parading himself in front of many thousands of onlookers as the undisputed new king and national figurehead of his late father’s realms. By the time the colossal entourage had finished snaking its way into the Abbey it was 5.00pm, and very late indeed before the funeral sermon, two hours in length, and other ceremonial rites had concluded. Although an impressive sight, and costing in all around £50,000 to execute, Chamberlain could not help but comment in hindsight that the order was at times ‘very confused and disorderly’. Clearly some people could never be wholly satisfied.

The reign of King Charles I was a troubled one, damaged by clashes with his recalcitrant Parliament, whom he famously did away with for 11 years between 1629 and 1640, and ultimately suppressed by a catastrophic civil war which ended in total disaster for the English monarchy. The exceptional nature of Charles’ death in 1649 meant that his laying to rest, when it came, would be worlds apart from the considerable solemnity and pageantry observed at his father’s funeral a quarter of a century earlier. Charged with high treason following the seven-year conflict with Parliament known to posterity as the English Civil War, Charles was put to death by beheading on a cold winter’s morning in January, as we have already discovered. On the executioner’s strike, successful in severing the king’s head on the first attempt, the centuries-old English constitution was thrown into complete disarray. Kingship was effectively abolished.

Consequently, Charles’ funeral was, by a king’s standards at least, a small and discreet affair. It offered a tantalising flavour of the royal funerals of the early seventeenth century without being able to fully realise their unrivalled majesty and scale. William Juxon, the Bishop of London, and Sir Thomas Herbert, the deceased king’s gentleman of the bedchamber, saw to it that Charles’ body was coffined and covered with a black velvet pall straight from the scaffold. The corpse was embalmed soon afterwards. Next there was some disagreement over where exactly King Charles should be buried. Herbert insisted that the Henry VII Chapel, located in all its grandeur at the east end of Westminster Abbey, represented the perfect spot, for here lay the bodies of earlier monarchs and members of the king’s own family, including Edward VI, Mary I, Elizabeth I, Mary, Queen of Scots, James I, and James’ eldest son, Prince Henry. The Abbey was unsurprisingly denied by those ‘that were then in power’, the reason being that it would attract too much unwanted attention from the public. It was eventually decided that the king’s body would be interred within the more secluded precincts of St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle.

With a burial location approved, Charles’ corpse was duly carried to Windsor in a hearse covered with more black velvet, drawn by six horses that had likewise been draped in black. Four coaches rattled along behind the initial spectacle, conveying about ‘a dozen gentlemen and others’ out of London to Windsor in black garments, most of whom it was reported had waited on the king during his imprisonment at Carisbrooke Castle. Arriving at its destination, the royal corpse was carried through the Dean’s House and placed in the king’s usual bedchamber at Windsor Castle. Meanwhile, having assembled in the wake of Charles’ death, a prominent band of noblemen deliberated over where in St George’s Chapel to bury the body. As the search was conducted, one of the lords present was said to have experimentally beaten his staff against the stone pavement in the choir, causing a hollow sound to emanate from beneath the floor. An order was given to remove the various ‘stones and earth’ covering the ground, which revealed a vault housing two grand coffins, both adorned with velvet palls. It was supposed that these contained the bodies of King Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour. The discovery beneath the choir soon made up the minds of the indecisive searchers.

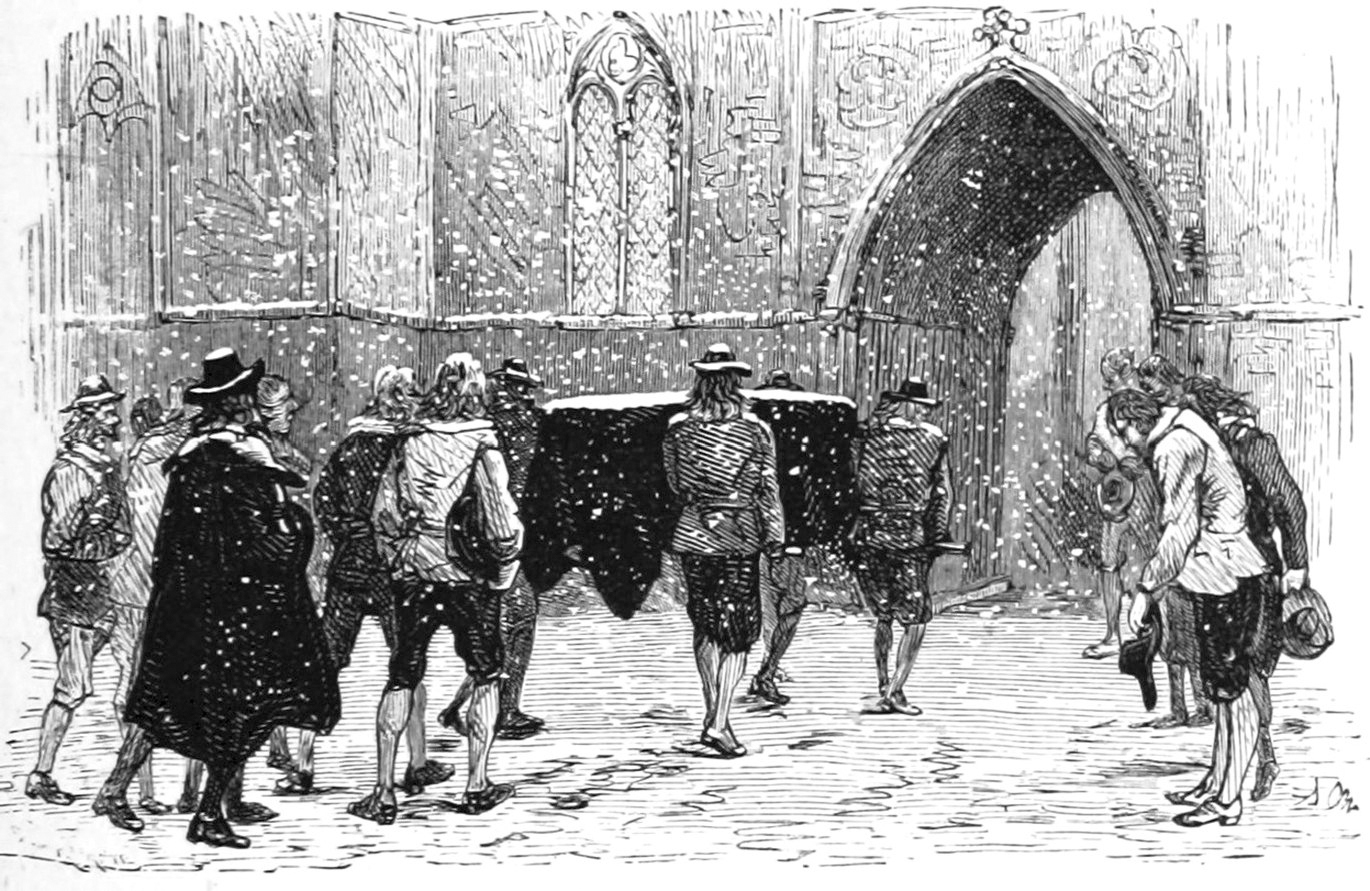

Charles’ body was carefully removed from its temporary repose in the private quarters of Windsor Castle, and, after sitting for a little while longer in St George’s Hall, the coffin was carried by gentlemen of ‘some quality’ to the west end of St George’s Chapel. Circumstances dictated that the funeral procession was modest at best for a sovereign, with only a handful of lords, governors, and attendants following the corpse to its final resting place under the choir. The day’s events, however, were regarded by some as entirely fitting, and even rather beautiful. The sky was said to have been ‘serene and clear’ at first, but then we are told it began to snow, coming down so fast that by the time the procession had reached the west end of the Chapel, the black velvet pall covering the coffin had turned ‘all white’: the colour of innocence. Leaving the thick sheets of snow outside, the king’s bearers, followed by the procession, entered the Chapel quietly and purposefully, with no baying crowd or wailing audience to disturb them. Charles had died in a manner that was both violent and agonisingly public, but on his funeral day the tempest encircling his execution had all but blown away. He was able to have an intimate and peaceful interment.

Almost immediately after the extraordinary beheading of Charles I, concerted efforts were made to formally write the monarchy out of the English constitution. The remnants of the House of Commons came together in February 1649 and carried a resolution ‘that it had been found by experience…that the office of a king…is unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interests of the people of this nation, and therefore ought to be abolished’. As a result, a Council of State was duly set up to manage home and foreign affairs, headed by an eminent Parliamentarian and distinguished military leader named Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell had played a decisive role in the recent civil war and the unprecedented execution of the former king. It is one of history’s great ironies that, in assuming the elevated status of Lord Protector of the newly established Commonwealth, Cromwell himself became a king in all but name. His funeral in 1658 was certainly evocative of a sovereign’s, continuing in an assured manner the trend of unequalled pomp and solemnity, conducted on a huge scale, that had characterised the funerals of both Queen Elizabeth and King James. Indeed, in a time of great constitutional uncertainty, it was perhaps more important than ever before to showcase the authority and stability of the country’s leadership through an extravagant state occasion.

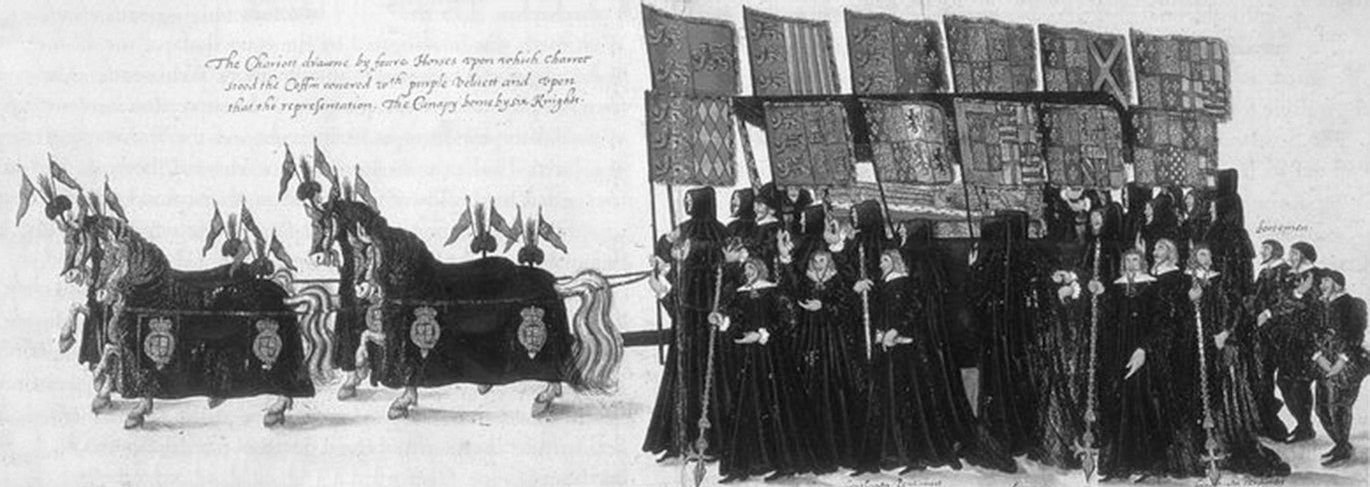

22. An 1877 drawing of the funeral of Charles I in 1649. The circumstances surrounding the king’s death meant that his funeral was an unusually subdued affair, with only a modest procession accompanying his body to St George’s Chapel at Windsor. Snow fell that day, which led some to speculate that it was a sign of his innocence.

It was the death of Cromwell’s daughter, Elizabeth, on 6 August 1658, that triggered the rapid deterioration in the Lord Protector’s own health. Soon it became apparent that he was also dying. Cromwell was perfectly aware of his impending demise, of course. He uttered knowingly in the last few weeks of his life that, ‘I would be willing to be further serviceable to God and His people, but my work is done’. Death eventually came on 3 September, just under a month after the loss of Elizabeth, blamed at the time on a generic ague but now thought to have been the result of a deadly strain of malaria. Cromwell had been regarded as a monarch merely without the regalia in life, and in death there would be no difference in attitude. Just as he had lived like a king, he would also now be buried like one. In the usual ceremonial manner reserved for members of the English royal family, the Lord Protector’s coffin was conveyed from Whitehall to Somerset House on the night of 25 September, where a lying-in-state would be observed until the day of the funeral. There was speculation that the coffin was in fact empty by the time it had embarked on its nocturnal journey through London. Contemporary reports indicated that the embalming process on the corpse had gone wrong, leaving Cromwell in such a sorry state physically that he had been deemed unsuitable for public exhibition, even when coffined. A commentator wrote:

‘His body being opened and embalmed his milt was found full of corruption and filth, which was so strong and stinking, that after the corpse was embalmed and filled with aromatic odours, and wrapped in a ‘cere-cloath’, six double, in an inner sheet of lead, and a strong wooden coffin, yet the filth broke through them all, and raised such a noisome stink, that they were forced to bury him out of hand.’2

Whether or not this was mere hearsay or slander is up for debate, but what can be established with certainty is that Cromwell’s body was buried in private at an undisclosed time before the day of the funeral. A wax effigy of the Lord Protector, which was to be displayed at his lying-in-state and carried to Westminster Abbey in the funeral procession, would at any rate do more than justice to the corporeal man.

Those wishing to view the initial lying-in-state were guided through four rooms hung with copious amounts of black velvet, the fourth being the most sumptuously and melancholically decorated of all, and containing the wax figure of Cromwell. The likeness could be found positioned beneath a large, black canopy, the bed supporting it surrounded by four pillars topped with beasts featured on the ‘Imperial Arms’, eight silver candlesticks aglow with lit tapers, and a suit of armour. The effigy itself communicated a powerful and unmistakable message of regality and kingly authority. It was dressed in a ‘kirtle robe’ of purple velvet, decorated with gold lace and trimmed with ermine fur, and draped over the top of this garment was a large, purple robe also finished with ermine fur, as well as ‘rich’ strings and gold tassels. Strapped around the kirtle was a ‘rich embroidered’ belt set with a ‘richly gilt’ sword. The wax hands poised on either side of the belt held aloft in the candlelight two important objects: in the right was a golden sceptre, ‘representing government’, and in the left could be discerned a globe, an emblem of ‘principality’. Yet the most telling monarchical feature of all was to be located on a golden chair behind the reclining figure, for here, placed conscientiously atop a cushion, lay the Imperial Crown. By the time the effigy had begun its procession to the Abbey on

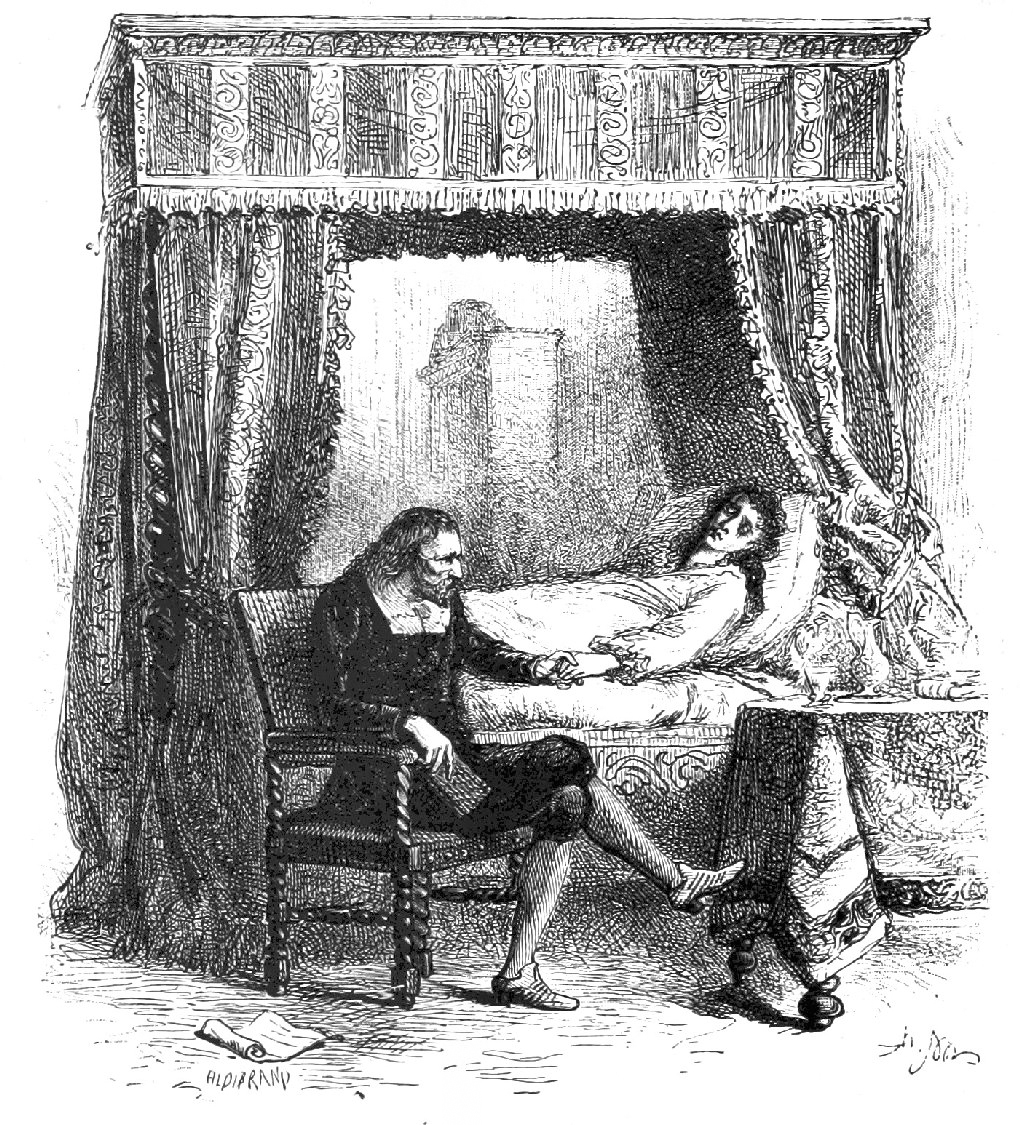

23. An 1877 drawing of Oliver Cromwell sitting with his daughter, Elizabeth Cromwell, as she succumbs to a terminal illness. The pair are shown holding hands.

24. Oliver Cromwell’s lying-in-state at Somerset House, London, in 1658, engraved by James Caldwell in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century. His lofty position as Lord Protector entitled him to a kingly death. This usually included an elaborate display of the regal coffin or effigy in the interim between the death of the monarch and his or her funeral. In Cromwell’s case an effigy was placed in a room hung with black velvet, watched over by mourners. It is thought that Cromwell’s body was buried many weeks prior to his funeral occurring.

23 November, the Crown would find itself positioned on the Protector’s wax head for all to see.

The funeral procession of Oliver Cromwell was every bit as magnificent as the royal funeral parades that had predated the unfortunate reign of Charles I. The diarist John Evelyn thought that the day’s offerings were nothing short of ‘superb’. He recalled how Cromwell’s effigy was carried from Somerset House in a ‘bed of state’ drawn by six horses, and noticed the Imperial Crown on the effigy’s head, perceiving that it made the Lord Protector look like a king. Evelyn further remarked that, ‘there was none but cried, but dogs, which the soldiers hooted away with a barbarous noise; drinking, and taking tobacco in the streets as they went’. Indeed, as much as this event was essentially billed as a royal funeral procession, it also possessed the unambiguous qualities of a military pageant, with soldiers in attendance all along the route and army officers assuming key roles in the glittering procession. Surrounding the carriage that supported the effigy, in prime position, were eight such officers, who held several pieces of Cromwell’s armour in their arms, a further nod to the military significance of the occasion.

Many thousands of spectators turned out to pay their respects to Cromwell on that joyful November day in 1658. It was an enthusiasm for the Lord Protector that would not last long. Oliver’s eldest son, Richard Cromwell, succeeded his father as Lord Protector on the former’s death. It immediately became obvious that he lacked the skills necessary for the position that had been handed down to him. A series of disagreements with the New Model Army, who had been so faithful to the first Lord Protector, ultimately paved the way for Richard’s resignation from office only nine months into his term. With the second and final Lord Protector withdrawing meekly from the national stage and the foundations of the Commonwealth noticeably buckling, calls were made to wipe the constitutional slate clean and reinstate the time-honoured English monarchy, which had now been absent in England for a decade.

On 29 May 1660 the Restoration of the monarchy was successfully achieved with the arrival of Charles I’s son, now King Charles II, into London to widespread celebration. It was a political shift that swiftly served to sour the once respected Cromwell name. Richard Cromwell was able to live out the rest of his years quietly, living mainly abroad but returning to England towards the end of the century and dying in his eighties in 1712. Oliver’s corpse was not so lucky. In January 1661 the carcasses of the late Lord Protector, John Bradshaw (the judge who had condemned Charles I to death), and the Protector’s son-in-law, Henry Ireton, were ‘dragged from their tombs’ and taken to the gallows at Tyburn on the orders of Charles II, where they were strung up for several hours in a morbid demonstration of posthumous hanging before being taken down and decapitated. The headless corpses were buried in a deep pit below the gallows, while the rotten heads were taken to Westminster Hall to be exhibited on spikes. This was to be the men’s punishment for having a hand in the death of the king’s father. The gruesome exhumation was a far cry from the resplendent and reverential funeral held for Cromwell only two years before, and was enough to unravel everything that the Lord Protector’s original burial had symbolised: adulation, authority, and above all, sovereignty. As John Evelyn wrote wryly after the event had taken place, ‘look back at November 1658 and be astonished’.

The reign of Charles II stretched on for a quarter of a century before the king found himself on his deathbed in early 1685. The monarch’s life began to ebb away on the morning of 2 February, when Charles rose early complaining that he had not slept well the previous night. Soon afterwards he collapsed, having suffered a suspected apoplectic fit. By 5 February, a Thursday, the king’s doctors announced that he was dangerously ill. All manner of remedies had been administered to the dying sovereign in an attempt to save his life, including bloodletting and blistering agents, provoking some to liken the room in which the king lay to a torture chamber. Although a few had temporarily relieved Charles of his symptoms and had on one occasion returned his speech to him, in the end they were none of them to any avail. Charles II died at the age of 54 on 6 February, a mere four days after he had first been taken unwell. Before the rattle came, he had controversially renounced his Protestant faith and was received into the Catholic Church.

The king’s funeral occurred, for the standards of the time, relatively soon after his decease. John Evelyn was underwhelmed by proceedings, observing that on the night of 14 February the king was ‘very obscurely buried’ in a vault under the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey ‘without any manner of pomp’. There were murmurs in London that the discreet nature of Charles’ obsequies was a result of his conversion to Catholicism, although it later transpired that the king was buried ‘according to the liturgy of the Church of England’. Nonetheless, Gilbert Burnet, who would later become Bishop of Salisbury, concurred with Evelyn that the funeral was a ‘mean’ affair, that the expense of it was considerably less than the average nobleman’s burial, and that the late king deserved better from his brother, the newly reigning monarch James II.

That the funeral was held at night may have misled contemporary writers into believing that the ceremony was more low-key than was actually the case, although it is highly possible that the occasion did embrace a sense of intimacy not present at the burials of monarchs earlier on in the century. As has been mentioned already, a nighttime funeral allowed for a more personal and private atmosphere. In actual fact, Charles II’s obsequies were said to have followed all the usual conventions of a sovereign’s death and funeral, commencing with a lying-in-state, complete with royal effigy, and culminating in a nocturnal procession to Westminster Abbey. King James and his wife, Queen Mary of Modena, were in attendance, as was Prince George of Denmark – the husband of King James’ daughter, Princess Anne – who assumed the role of chief mourner. The trials endured by the English monarchy in the middle years of the seventeenth century meant that Charles’ was the first interment of a monarch in Westminster Abbey for 60 years, since the burial of his grandfather James I in 1625. The Abbey’s next royal interment, the last of the century, would come around much faster.

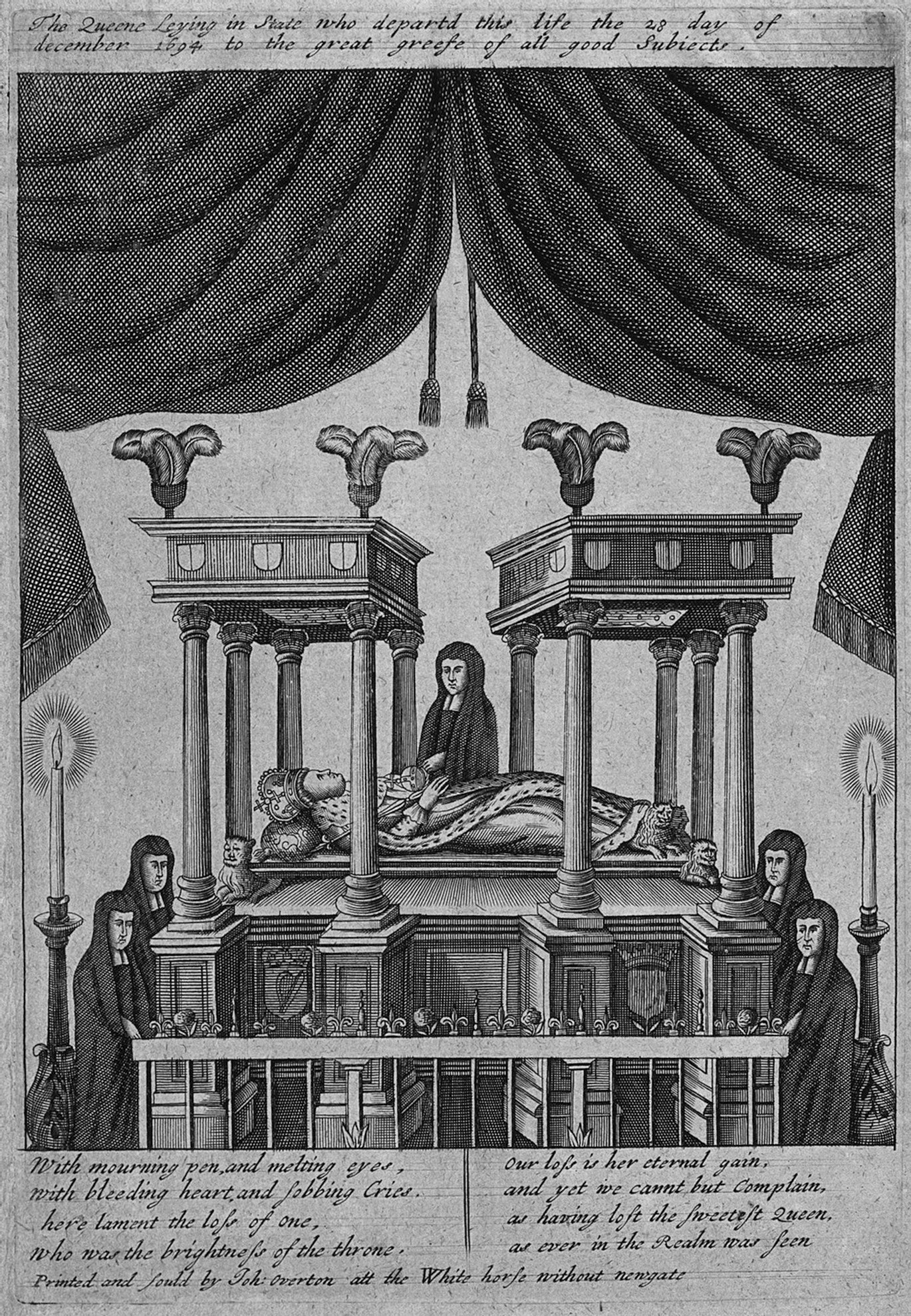

James II’s hold on the English crown was short-lived. Being an open Roman Catholic in a Protestant country ultimately lost him his throne, and in 1689 he was replaced by his son-in-law, William of Orange, and William’s wife, the ex-king’s eldest daughter, Princess Mary. They would rule jointly for just under six years as William III and Mary II, until smallpox robbed William of his queen prematurely in December 1694. The manner of Mary’s death was all the more tragic because she had been struck down with the illness once before and miraculously survived. Upon the second contraction of smallpox her luck had run out. William was said to have been left broken by the loss of his wife at the age of just 32. With the king’s sorrow came an outpouring of genuine anguish from the nation, who had held the late queen in high esteem and shown her particular affection because she was English. Now a Dutchman remained as the sole ruling monarch in a foreign land and the country was left bereft.

Mary II’s funeral was to be hugely impressive, the likes of which had probably not been seen for a monarch since the obsequies observed for Elizabeth I almost a century before. It certainly easily outstripped the nighttime solemnities of Charles II’s burial in the 1680s. Some argue that the exemplary pomp and ceremony of the queen’s funeral, which was held on 5 March 1695, merely constituted a clever piece of propaganda intended to strengthen the legitimacy of both Mary’s and particularly William’s claim to the throne, the latter being a notoriously unpopular ruler. Those less sceptical and present on the day might have viewed the solemnities as an appropriate farewell to a highly respected monarch.

Mary’s lying-in-state was set up in a room at Whitehall Palace hung with purple velvet, the colour of royalty, with ‘large wax tapers’ scattered across the floor and veiled ladies of the bedchamber positioned at the four corners of the queen’s bed, performing a devoted vigil. More veiled maids were attendant in an antechamber finished with purple cloth, and in another room were to be found pages dressed in black. The king invited members of Parliament to wear mourning clothes and to take part in the funeral procession, an oddity that no doubt added to the pageantry and uniqueness of that March day. The frail King William himself did not attend the funeral. The procession was without question an admirable affair, being the perfect blend of solemn observance and theatrical performance, which was embodied most perceptibly in the long line of mourners who filed from Whitehall to Westminster Abbey. The verdict of the traveller Celia Fiennes reinforces the impressive quality of Queen Mary’s funeral and the great impact it clearly had on the watching masses, she observing confidently that the king ‘omitted no ceremony of respect to her memory and remains’. Evelyn, too, thought that the funeral must have been ‘infinitely expensive’, for never had there been ‘so universal a mourning’:

‘All the Parliament-men had cloaks given them, and 400 poor women; all the streets hung, and the middle of the street boarded and covered with black cloth. There were all the Nobility, Mayor, Aldermen, Judges, &c.’3

If Evelyn is to be believed, then such an eccentric display was not what Mary II had in mind for her obsequies at all. Private papers left behind by the queen supposedly requested that her funeral should not amount to any ‘extraordinary expense’. Her modest wishes, however, were discovered too late in the day to be effected, and so there was instead no expense spared.

The procession having entered the Abbey, the customary funeral sermon was preached, during which Queen Mary’s body was ‘reposed in a mausoleum in the form of a bed’, finished with black velvet and a ‘silver fringe’. Hanging in the mausoleum’s arches and placed at its four corners were tapers of an undisclosed type, perhaps cradling small flames. In the middle of the structure a basin supported by the shoulders of cupids held a ‘great lamp’ that burned throughout the service.

25. The lying-in-state of Mary II of England in 1695, etched by John Overton. The queen is surrounded by purple velvet, columns, and lit tapers. Her ladies of the bedchamber perform a devoted vigil.

Fiennes reported that the sermon was accompanied by ‘solemn and mournful’ music, and singing too, reverberating around the cavernous Abbey to the same rhythm as the flames that flickered in the centre of the mausoleum. Finally, before the sealing of the tomb, white staves were snapped by the queen’s officers and thrown into the royal grave, symbolising that their service to her was done, just as had happened at the burial of Queen Elizabeth in the same Abbey 92 years before. Then the tomb was sealed, and the last royal funeral to be held in seventeenthcentury England was over. The similarities between Queen Mary’s funeral in 1695 and Queen Elizabeth’s in 1603 show just how little the funeral rites of English royalty changed over the course of the century, on those occasions when royal obsequies could indeed be expressed freely and openly. As was underlined at the beginning of this chapter, royal funerals were like little else observed in the insular world of preindustrial England. They strove to impress, and this is what ultimately made them one-of-a-kind events.