‘My wretched body to be beryed in my Charterhouse at Hulle, where y wol my ymage and stone be made and the ymage of my best beloved wyf by me, she to be there with me yf she lust, my said sepulture to be made by her discretion in ye said Charterhouse where she shal thinke best, in caas be yat in my dayes it be not made nor begonne.’1

Thus went the will of William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk, in 1450. Suffolk’s desire for his likeness to be posthumously evoked through the construction of a church monument shows that the English had been concerned with personal commemoration after death since the late medieval period and before. Remembrance practices were nothing new in the seventeenth century, therefore, but they were arguably more significant than they had been in medieval England. By the 1600s, the communities of the living and the dead had been wrenched apart to a degree unheard of in pre-Reformation times. The abolition of intercessory prayer in the sixteenth century, provoked by Protestant rejection of the doctrine of Purgatory, had helped to promote a peculiar sense of finality at the moment of death. Once somebody was dead, they were now truly gone. Methods of remembrance became especially important for a society that collectively feared the plunge into instantaneous, permanent obscurity. Memorialisation of the individualistic qualities of a person, in particular, was craved as it had never been before.

Elaborate monuments or tombs continued to be favoured by members of the nobility in seventeenth-century England as a way in which to be remembered following death’s oblivion. Enshrined in the hallowed recesses of the parish church, these erections were chiefly commissioned to commemorate the social status and local influence of the late aristocratic man or woman, and to ensure that they retained a presence of authority in the parish long after their bodies had turned to dust.

Noble testators sometimes specified the kind of monument they wanted when writing their wills, just as William de la Pole had done over 150 years earlier. Some instructions were more exact than others. In 1631 Sir Hugh Myddleton, ‘cittizen and gouldsmith of London’, merely willed that a monument should be set up for him in St Matthew’s Church at the discretion of his executrix. Sir William Cornwallis of Brome went into much more detail in 1611:

‘…my will and mynde is to have one Tombe or monument to be…made for my self with mention of both my wives (viz) of the Ladie Lucie my late wife Deceased…and of Dame Jane my nowe wife and of all my Children And alsoe one other Tombe or monument of plaine stone to be there likewise made and erected in the saide Chancell for my great Grandfather William Cornewaleis Esquire whoe lyeth buried there with a stone over him.’2

As is evident, there was as much a concern for the memorialisation of familial relationships as there was for the prominence of the individual testator in Cornwallis’ directions. The Suffolk knight wanted his monument to commemorate the network of kinship that had surrounded him in life, and how he had been positioned within that network: first and foremost, he was the husband of two wives and the father of several children. With the addition of a new tomb for his ancestor nearby, he would also be remembered as the great-grandson of an esquire. Dame Anne Wingfield made a similar move in 1625, desiring in her will that she be buried in a tomb next to her first husband’s in the parish church of Letheringham; the two monuments, sitting side by side, would work together to commemorate their prestigious marital union. We know that this is exactly what went on to happen. Through the observations of Robert Hawes, an early eighteenth-century steward of the Framlingham Estate, it is confirmed that Dame Anne was duly buried in a tomb by that of her late husband’s, as she had gone to great pains to request. It was described as ‘a black marble stone plated with brass having the form of a woman with hands in praying posture delineated thereon’. Under the feet there was an inscription, memorialising in a simple way the Wingfields’ earthly marriage:

‘Here lieth the body of Lady Anne Wingfield…first married to Sir Anthony Wingfield of Letheringham […] She died the Second of August. Anno Domini 1626.’3

Regrettably the monument no longer exists, along with many others that were first planned in wills.

Surviving church monuments from the seventeenth century are on the whole successful in memorialising the aristocracy as high-status individuals as well as family members. The parish church of St Peter and St Paul in Kedington, Suffolk, is often described as the Westminster Abbey amongst village churches due to its unusually high number of monuments, including tombs and effigies. The effigy of Sir Thomas Barnardiston, a wealthy landowner who died in 1610, can be observed within its walls clad in decorative armour, the hands clasped piously against the breastplate, the head resting (surely uncomfortably) on a plumed helmet. Barnardiston’s two wives kneel in prayer above him, capturing in sculpted stone, in a rather submissive pose it must be said, the nobleman’s immediate family. However, the imposingness of the monument and its blunt imagery suggests that this was ultimately a display of superiority, both on a parish and familial level. The Alington monument found in All Saints’ Church in Horseheath, Cambridgeshire, does an altogether better job of memorialising the personal relationships of the landed gentry in the seventeenth century. Importantly, it also brings to mind the grandeur of the Alingtons’ circumstances and the foremost space they occupied in the village of Horseheath. Erected in 1613, the alabaster monument is somewhat faded nowadays, but at the time of its construction it would have been sumptuously painted and gilded, gleaming like a jewel in the otherwise whitewashed chancel. It remains an impressive piece of craftsmanship. The resplendent effigies of Sir Giles and Lady Dorothy Alington, one bedecked in a suit of armour and the other a fine dress, take centre stage. The couple’s stateliness is unmistakable through the extravagant design of the structure, which extends up the chancel wall in a flourish of marble and finishes with an array of ancient crests. Yet there is very strong familial symbolism here too. Unlike Barnardiston’s monument, in which his effigy is physically removed from those of his devoted wives, the statues of Lord and Lady Alington lie next to each other in their eternal rest, immortalising the close affiliation they shared in life as man and wife. The Alingtons are concurrently commemorated as parents at the base of the monument, where the carvings of six kneeling children are presented, one of which holds a death’s head in its hands. The inscription cements the familial tone of the commemoration:

‘Here resteth in assured Hope to rise in Christ Sir Giles Alington of Horseheath, Knight, accompanied with Lady Dorothy, his wife, Daughter of Thomas Earle of Exeter, Baron Burghley, and who made him a joyfull Father of tenne Children (Elizabeth, Thomas, Giles, James, Dorothy, Susan, Anne, Catherine, William and Mary), [who] ended this transitory life the 10th November 1613, to whose dear memory her sorrowful Husband mindful of his own mortality erected this monument.’4

One cannot ignore the religious mood of the Kedington and Horseheath monuments. The gestures of prayer displayed by each of the effigies implies a clear dedication to faith that both the Barnardistons and Alingtons hoped to isolate in representations of their future selves. It is only a shame that the likeness of Lady Dorothy no longer has hands.

Church monuments came in a variety of forms in seventeenth-century England. At the turn of the century alabaster or marble sculptures were all the rage, as we have already discovered in the above examples. They didn’t come cheap though. The marble monument dedicated to the memory of the politician James Whitelocke, which still stands proudly in the church at Fawley in Buckinghamshire, cost the sizeable sum of

£114 to make and paint in 1633. It could be a lengthy process. Sir Ralph Verney’s monument for his deceased wife, which was to employ a mix of black marble, white marble, coloured marble, and alabaster, took several years to complete from the planning stages to the finished product in the 1650s. Sir Ralph launched the project before Mary’s body was even cold. On her death in August 1650 he wrote to Dr William Denton straight away to instruct him to take measurements in the chancel of Middle Claydon parish church, and to mark where the monument was going to be erected. Denton was told to then describe his findings to an appropriate craftsman. ‘Send me two or three draughts on paper drawne Black & White, or in Colours as it will bee’, Ralph dictated, ‘that I may see which Toombe I like best’. By 1651 it had been decided that the Frenchman Monsieur Duval should be entrusted with overseeing the creation of Mary’s ornate tomb, with the work to be done at ‘one of the best stonecutters’ houses in London’. Ralph had a very clear idea of what he wanted the marble feature to look like. Writing to Dr Denton again on 23 September 1651, a year into the assignment, Verney described his vision for the anticipated masterpiece in obsessive detail:

26. The tomb of Sir Thomas Barnardiston in Kedington church, Suffolk. It was erected following Thomas’ death in 1610 and is a classic example of an early seventeenthcentury church monument dedicated to a member of the English aristocracy.

‘Now for a Tombe, ye chancell being little…I was thinking to make an Arch of Touch [black granite] or Black Marble; within the whole Arch shall bee black, & her statue in White Marble in a Winding sheet with her hands lift upp set uppon an Urne or Pedestall uppon which or on ye edge of ye Arch may bee what Armes or Inscriptions shall bee thought fit. I was thinking to make a double Arch and in it to set upp her statue, & only leave a Pedestall for mine, for my sonn to set upp, if hee thinke fit, but I doubt this would bee thought vanity, being there is non for my Father & Mother, but if it please god to give me life & my estate, I will set up a tombe for them.’5

27. The two wives of Sir Thomas Barnardiston kneeling in prayer, almost submissively, above his effigy in Kedington church.

Six months later sketches were still being passed between Ralph and his designers, some of whom lived as far away as Rome. Mary had been dead for nearly two years by this point. Needless to say the monument would not be completed properly until the middle of the decade.

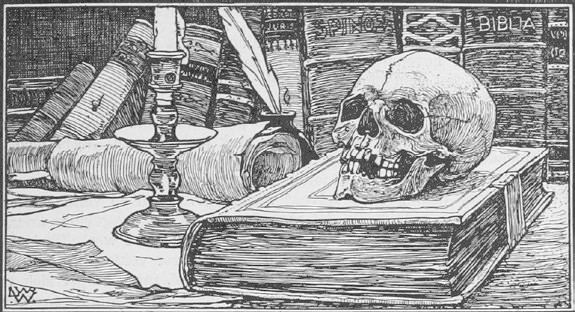

Monumental brasses were an economical type of sepulchral memorial installed in churches by the gentry, and the middling sort to an extent, in the seventeenth century. They had been popular since the medieval period and continued to be commissioned until the 1700s. It is estimated that a few thousand of these brasses still survive in the twenty-first century, including those pertaining to the Martin (or Martyn) family in Long Melford church, Suffolk. The handsome brasses are fixed to the stone floor of the south chancel aisle and might be missed entirely by the unaware visitor. On the right-hand side facing towards the tower is a fine-looking example from 1615, commemorating the esquire Roger Martyn, who died at the remarkable age of 89. He is dressed in a long gown and flanked by his two wives, Ursula and Margaret, who are wearing French hoods and ruffs. All three of them stand united in prayer on pedestals. Below these circular platforms is the modest inscription, identifying the man who has been depicted in brass and whose body lies beneath the dark slab, and further down there are two more miniature plates portraying the couple’s children. On the left-hand side is a separate brass from 1624. The stress placed on family and hierarchy here is even greater, with the monument’s central figure and subject, Richard Martin, surrounded by three elegantly outfitted wives, two infants in swaddling clothes, and two older sons, the younger of whom holds a skull to his chest. At least one other plate that made up the memorial has been lost, leaving a near-imperceptible imprint in the floor.

28. A monumental brass depicting Roger Martyn and his family in Long Melford church, Suffolk, c.1615. Such monuments were a cheaper alternative to the alabaster memorials seen elsewhere and had been popular since the medieval period.

29. A second monumental brass in Long Melford church portraying Richard Martin, his wives, and his children, c.1624. The familial tone is particularly strong in this brass, as it includes images of two infants in swaddling clothes.

The passage of time brought with it changes to the intrinsic qualities of church monuments. Protestantism encouraged posthumous secular imagery to blossom. Physical death became more overtly represented in monumental designs in the later seventeenth century, as seen in the c.1660s wall memorial to Nathaniel and Jane Barnardiston inside Kedington church, where the two marble effigies, looking rather weary, each rest a hand on a skull. The late seventeenth-century Wentworth monument in the south aisle of the Lady Chapel in York Minster has a large and austere funeral urn as its centre, with the flowing figures of William Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, and his wife, Lady Henrietta, positioned on either side of it, seeming somehow to be cast in its shadow. The structure, columned and made of heavily veined marble, provides a flavour of the neoclassical architectural style that would take the upper classes by storm in the next century. The Wentworth monument is reflective of another development in the style of English memorials during the seventeenth century. Unlike the Barnardistons and the Alingtons of the 1610s, the Wentworths are standing up in their commemorative feature of the 1690s. This was a

30. A wall monument dedicated to Nathaniel and Jane Barnardiston, c.1660s. Their upright likenesses each rest a hand on a skull in the centre of the memorial. Physical death was more overtly represented in monuments in the later seventeenth century as part of the rise of Protestant secular imagery. significant departure from the recumbent pose of earlier effigies and was probably intended to allow a superior level of interaction between statue and observer. Frequenters of the Minister could stare straight into the marble faces of Lord and Lady Strafford, and they in turn could gaze back. The upright postures of these and other monumental bodies, moreover, might enhance the posthumous authority of the aristocracy. William and Henrietta exude a confidence and majesty in standing that cannot be matched in effigies that are deferentially lying down.

The middling sort, if indeed they were lucky enough to secure an interior burial, brought simpler memorials through the doors of the parish church in this period. These were occasionally asked for in wills. William Fuller of Syleham, gentleman, willed in 1629 that his executor see him buried near his late wife in the chancel of Syleham church, ‘and…lay a decent stone or stones over our graves within one year of the day of my burial’. In 1620 the yeoman Reginald Burrough similarly instructed that, ‘a gravestone is to be laid over [my] grave with a remembrance thereon who lies under it’ in Bungay church. The ‘practitioner in physic’ Edmond Harris was extraordinarily specific about his memorial in Henstead church in 1622. Although its overall appearance was to be modest, its anticipated words were to be worth more than the riches of the aristocracy. Harris’ executor was assigned the task of ‘bestow[ing] on a gravestone of marble, six foot long and three foot broad’ the following inscription:

31. A winged skull, part of the wall monument dedicated to Nathaniel and Jane Barnardiston, c.1660s.

32. The splendid white marble monument in York Minster commemorating William Wentworth, 2nd Earl of Strafford, and his first wife, Lady Henrietta. Henrietta died in 1685, while William joined her 10 years later at the age of 59, leaving no issue. The monument features two effigies standing up, allowing for a greater level of interaction between statue and observer. Between them rests a prominently positioned funeral urn.

‘Hereunder resteth the body of Edmond Harris, gent., practitioner in physic, who deceased the -day of -in the year of our lord God 16--, & of his age --, & by his side rests the body of his (said) daughter Anne Harris who died the -day of -in the year 1---, & of her age’6

The epitaph was to read:

‘Even suche a tyme that takes in trust, our youthe our Age and all we have, and paies us but with earth and dust, in darkesome night and silent grave, when we have wandered all our waies, and spent the Story of our daies, then from that grave of earth and dust, the Lorde will raise me uppe I trust’7

Both were to be engraved in brass. Harris’ epitaph, a reproduction of Sir Walter Raleigh’s final poem, indicates that he was submissively accepting of his fate as a mere corpse in a grave of ‘earth and dust’, silently awaiting the Resurrection. Perhaps this is precisely why he sought to include an inscription that acted as a reassuring remembrance of the living man and his daughter. The Harris example is an allusion to the post-Reformation desire in England for inscriptions to reflect more precisely the individualistic qualities of deceased persons.

No consideration of church memorials in seventeenth-century England would be complete without a mention of the royal monuments housed in Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth I’s can be found residing in the north aisle of the Henry VII Chapel, where it was installed by her successor James I soon after her death in 1603, at a cost of £1,485. It is a beautiful monument of white marble, capturing the queen’s regality even in her later years, but it would have been more striking when it was first constructed. The lions supporting the reclining effigy were originally gilded instead of pale, while certain features of the queen’s apparel, including her robe, dress, and orb, may have been coloured. The tombs of two of James I’s daughters were also erected in the north aisle of the Chapel and can be admired today along with Queen Elizabeth’s monument. Both were made by the Flemish sculptor Maximilian Colt, who was likewise responsible for the effigy of the kingly Elizabeth a few years before. The monuments are all the more touching because both girls lived only very briefly. Sophia was three days old when she died in June 1606. She is depicted sleeping in a fine cradle adorned with an attractive gold pattern, beneath a dark coverlet trimmed with lace. Mary, aged two when she perished, is shown nearby in the classic recumbent position, resting an elbow on a pillow. Her tomb is extraordinarily lavish for one so young; cherubs sit at the base, the main body is lined with gold, and a lion sits at the princess’s feet. The inscriptions appear to be attempts on the part of King James and Queen Anne to reconcile themselves to the loss of their small children. Sophia’s reads:

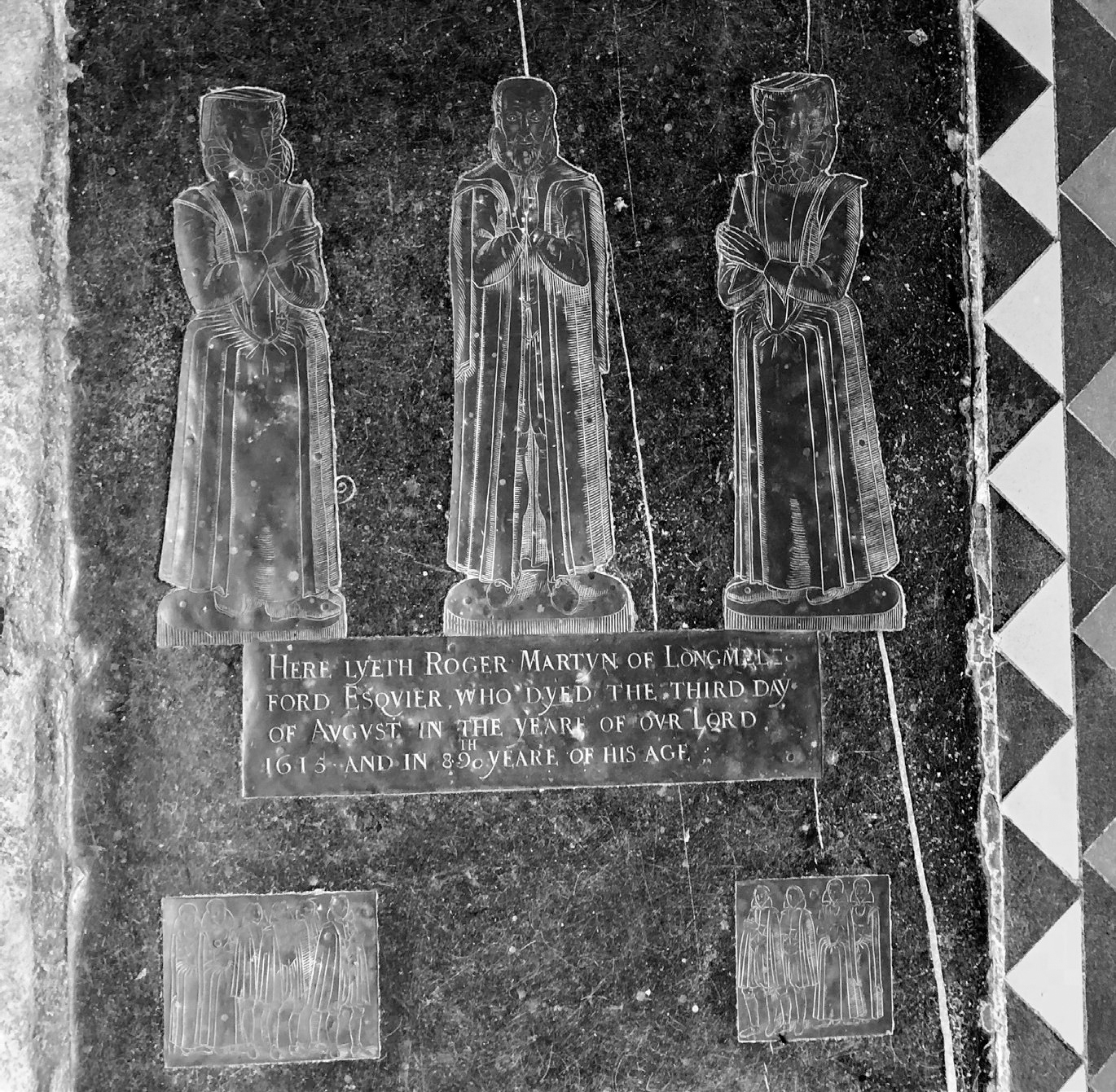

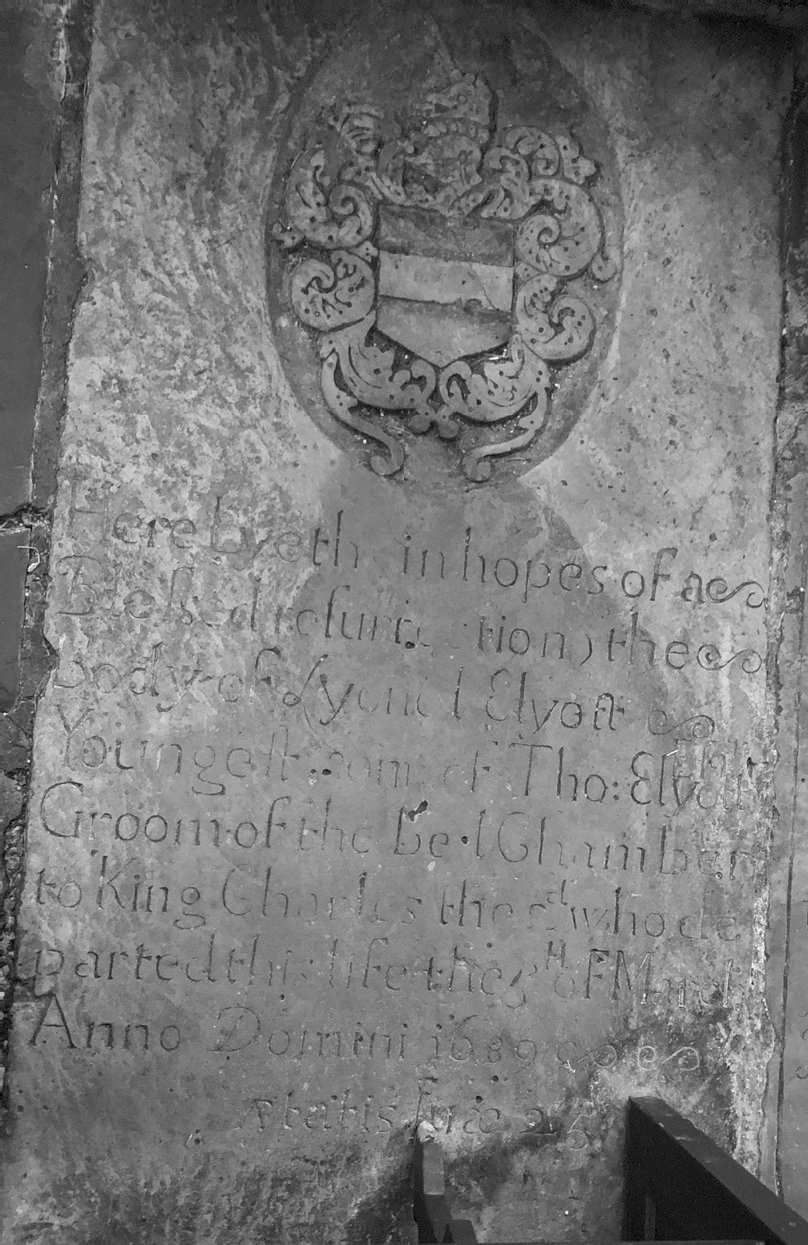

33. A modest seventeenthcentury gravestone set into the floor of Holy Trinity Church in Goodramgate, York, c.1689. The man buried beneath it had vague royal connections. The inscription reads: ‘Here lyeth in hopes of a Blessed resurrection the body of Lyonel Elyott Youngest sonne of Tho: Elyott Groom of the bed Chamber to King Charles the 2(n)d who departed this life the 5(T)H March Anno Domini 1689’.

‘Sophia, a royal rosebud untimely plucked by Fate and from James, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, and Queen Anne her parents, snatched away, to flower again in the rose garden of Christ, lies here. 23rd June, 4th year of the reign of King James 1606.’

Mary’s is no less heartrending:

‘Mary, daughter of James King of Great Britain, France and Ireland and of Queen Anne; received into heaven in earliest infancy, I found joy for myself and left grief to my parents. 16th December 1607. Those who wish joy ask sympathy. She lived 2 years 5 months 8 days.’8

Not all members of the English royal family were blessed with such thoughtful commemorations. Constraints on space in the Henry VII Chapel meant that Charles II was given no monument at all after he died

34. The tomb effigy of Queen Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey. The likeness of the monarch still reclines proud after 400 years of public display. The monument was commissioned by Elizabeth’s successor, James I, and was intended to be a posthumous display of regality and queenly splendour. It is a white marble feature bordered by black pillars and now gold-topped railings, with lions supporting its base. in 1685. A wax effigy of the king sat beside his grave for a hundred years instead. His niece, Mary II, faced the same problem in 1695, or rather her corpse did, which was appeased by the addition of a small stone to mark the spot where her body rested.

Moving now to the simplicities of the parish churchyard, those who were buried here might choose to be commemorated through the erection of a simple headstone. It was in the latter years of this century that headstones first began to be erected in English churchyards in significant numbers, in part due to the burgeoning desire from humbler men and women to be remembered in stone as their aristocratic counterparts were in churches. Designs remained mostly basic and devoid of eccentricity, echoing the status of the individual buried in the grave below. Chilham churchyard in Kent houses an excellent example of a seventeenth-century headstone dating from 1698. At its top is the amateurish image of a skull, the only decorative feature of the monument, while underneath lies a brief inscription detailing who is interred in the earth: Henry Knowler, husband of Frances and Ester Knowler. Within the grounds of St Mary’s Church in Cheltenham can be found nestled a slightly more elaborate gravestone from 1679, belonging to a man called William. The stone is edged with a wavy border that comes together at the uppermost point to form a curling summit. Erosion through the years has left the exact pattern difficult to discern.

The distribution of remembrance objects was a practice observed by a considerable part of the population in seventeenth-century England. Since the sixteenth century rings of varying styles had been the most popular offering, but other remembrances might include anything from family plate to an old nag. The culture of gift-giving in this context rested on the principle that the object presented would remind the recipient of the person who had gifted it. The dead individual, whoever they might be, would therefore be remembered through the object. Thus, in 1634 Edward Baldry of Ipswich, yeoman, bequeathed in his will 40 shillings to his cousins Joan, Elizabeth, and Mary, to ‘buy rings to wear as a remembrance of me’. A huge number of seventeenth-century wills include bequests of rings for this very purpose. The aristocratic testator, in particular, was keen to specify the type of remembrance ring he or she wished to bequeath to a beneficiary. Death’s head rings were a firm favourite, being gold pieces that featured morbid depictions of heads or skulls in their centres. Edmund Pooley of Badley, esquire, set aside in 1607 certain ‘sums’ to be made into ‘ringes with a Deaths head in

remembrance of me’, although he failed to name any beneficiaries. Pooley specified that his will had been written with his own hand. Dame Anne Wingfield of Letheringham bequeathed to each of her nephews and nieces ‘a Deathes head Ringe of fortie shillings for a Remembrance’ in 1625. More opulent types of remembrance ring were, likewise, given by high-ranking testators wishing to exhibit their status through bequests. Mary Cornwalleys of Ipswich, esquire’s widow, bequeathed in her will of 1631 ‘one Diamonde Ringe of five poundes’ to her ‘deare and loving brother’, desiring him to wear it ‘in memory of her’. Dame Catherine Carey of Little Stonham, widow, bequeathed to her sister ‘one Ringe of gould to be sett with 4 Diamonds made in the fashion of a harte of the price…of six Poundes thirteene shillings and foure pence’. Sir Ralph Verney sent a ring to his brother Henry on behalf of his deceased daughter Anna Maria in 1639. It contained a lock of the girl’s hair. ‘You shall herewithal receive a ring’, Ralph wrote. He explained that, ‘shee was fond of you, and you loved her, therefore I now send you this to keepe for her sake’.

There are examples of remembrance rings being used as bribes on occasion. Henry Beart of Hacheston, yeoman, bequeathed in 1624 a ring engraved with a death’s head to ‘friend’ Henry Ewen, ‘for his pains’ in being a supervisor of the will. The bequest was seemingly made to assure Ewen that he would receive some form of payment, or recognition, were he to agree to the role. Thomas Goodwyn’s will of 1635 provides a firmer example of this point. He willed the following:

35.A seventeenth-century remembrance (or mourning) ring, seen from different angles, c.1679. It is a gold piece decorated with plants and a skull and crossbones on its outside. Inscribed in the middle are the words ‘Mrs Sarah Doding died 26th Nov 79’. Mrs Doding was a resident of Lancashire. Rings were extremely popular in seventeenthcentury England as a means by which to be remembered, often being designed with a death’s head or skull.

‘I doe make my especiall frendes Harbottle Wingfield Esquire and John Sheppard of Mendlesham gent. to be the Supervisors of this my will And doe give to each of them Tenn poundes apiece to buy them a piece of plate in remembrance of my love to them…hopeing that they wilbe assisting to my Executor’9

Goodwyn hoped that by bequeathing to his supervisors ‘plate in remembrance of my love’, it would encourage them to be ‘assisting’ to his executor.

Plate was given liberally as a remembrance by wealthy testators in the 1600s. Sometimes it was to be bought as opposed to coming directly from the family dresser. Mary Cornwalleys, esquire’s widow, bequeathed a considerable £20 in 1631 to her cousin ‘to buy him a piece of plate for a remembrance of me’. Sir Thomas Cambell aimed to be remembered by every member of the Ironmongers’ Company in London in 1612 when he bequeathed to them £20 ‘to be ymployed in plate whereuppon I will have my name or Armes set’. Sir Humphrey Handford had the same idea 10 years later, in this case setting his sights on the Worshipful Company of Grocers, of which he was a member. In 1625 he willed:

‘Item I give and bequeath unto the master wardens and cominalty of the arte or mistery of Grocers in London, whereof I am a member, for a remembrance of my love, soe much plate as shalbe worth thirty and three poundes six shillings and eight pence, the same plate to be made of such fashion with my name thereon as they shall appoint.’10

Money on its own was a popular remembrance gift too, with men bequeathing it more frequently than women. George Brome, gentleman, bequeathed to his ‘Noble-friend and worthie Captaine’ Sir Thomas Glemham, ‘for a poore remembrance of my sincere affection and faithfull service towards him’, £40 in 1627. Through this bequest, Brome wanted to be remembered to Glemham as an affectionate and faithful soldier, but also as a friend. Arthur Jenney of Knodishall, esquire, used a bequest of money to be remembered as a doting parent to his daughters, willing in 1604 that one of them should receive ‘five poundes…in remembrance of my fatherly love and goodwill towardes them’.

Silver spoons were mentioned ubiquitously in wills, yet it seems that they were bequeathed to beneficiaries mainly on account of their monetary value. Husbandman Ralph Corbin of Weston, for instance, exemplifies the value placed on spoons in his will of 1622, mentioning that he had ‘pawned 4 silver spoons to sister Cottman’ for 20 shillings. Even though it is no great amount, that he pawned the spoons speaks volumes. However, Thomas Warde, a clothier from Needham Market, did bequeath his best silver spoons to his sons, daughter, and three grandchildren for ‘a remembrance’ in 1620.

The more unique remembrance gifts, found in isolation in a handful of wills, demonstrate that almost anything could be bequeathed as a ‘remembrance’ in early modern England. Alice Turner of Bungay, widow, desired in her will of 1622 that the ‘gossip Thomas Francklin’ receive ‘for a remembrance [a] wrought table napkin’ a month after her decease. The significance of such a bequest can never be known. Abrie Boteman of Badingham, spinster, bequeathed in her will of 1625 ‘a new piece of lawn’ (a kind of fine linen) to Anne Lyngwood ‘for a small remembrance’. At least two testators bequeathed desks. One of them, Stephen Rose of Wickham Market, yeoman, bequeathed to his son-in-law a ‘desk standing in the parlour chamber & a book’, both specifically termed ‘remembrances’. Lady Anne Clifford’s instructions in 1674 were undeniably exceptional. She wrote:

‘To my right honorable and noble grandsonne, Nicholas Earle of Thanett, one other gold cupp with a cover to itt, all of massie gold, which cost me alsoe about 100l., whereon the armes of his father, my deceased son-in-law, and of his mother, my daughter, and some of my owne armes, are engraven, desiring his lordshipp that the same remaine after his decease (if he soe please) to his wife, my honorable cossen and goddaughter, if she survive him, as a remembrance of me.’

Anne also wanted her father, George Clifford, to be remembered through a peculiarly aristocratic bequest:

‘To my honorable grandchildren, Nicholas Earle of Thanett and Mr. John Tufton, his brother, the remainder of the two rich armors which were my noble father’s, to remaine to them and their posterity (if they soe please) as a remembrance of him.’11

Ralph Josselin’s wife was given the customary ring to remember their friend Mrs Mary by in 1647. Ralph himself, much more bizarrely, was left a ‘silver tooth and eare pick’.

Horses were bequeathed to beneficiaries as remembrances on several different occasions in seventeenth-century Suffolk. On one occasion in 1627, George Brome bequeathed to his brother ‘my nagge as a remembrance of my love to him’. Thomas Roe of Walton, gentleman, gave to John Scrutton ‘the bay nag I usually ride in token of the old affection which was always between us’ in 1634. The horse was clearly given as a ‘remembrance’ – in all but name – of the ties of affection between the two men. The latter two examples are suggestive of a pervasive desire to use remembrance bequests as a way of recalling and reinforcing testators’ ties of affection, and thus their earthly connections, after death. Members of the gentry stipulated that bequests be remembrances of ties of affection across the period. Edward Bacon of Barham, esquire, bequeathed in 1613 to his ‘most lovinge and deare Sister…to whome I have been bound above all others a Ryng of twentie shillinges as a token of my last love’. Mary Cornwalleys of Ipswich, esquire’s widow, willed the following in 1631:

‘Item I give to my worthy aproved loveinge and kinde Nephew Mr John [Prishon?]…my Ringe with five Diamonds, the pledge of love betwixt my deare husband and me, which I desire him to weare for my sake.’12

This example is interesting because the bequest is seemingly used as an intended remembrance of the ties of affection between the testator and her husband, even though the beneficiary was Cornwalleys’ nephew. A thought-provoking observation is the desire in wills for ties of affection to be recollected posthumously between masters and their servants. Sir William Cornwallis of Brome, knight, bequeathed in his will of 1611 £10 apiece to his servants ‘for a remembrance of my love and good will towards them’. George Brome, as a kind of subservient figure, bequeathed many gifts to the Glemham family in remembrance of the ‘love’, ‘affection’, and ‘observance’ he showed them all in life. The Glemhams prospered under the Tudors, being by the early seventeenth century a well-established family based at Glemham Hall on the outskirts of Little Glemham, on the Suffolk coast. Gift exchange in these instances was probably the consequence of a paternalistic association. This is no doubt true of Sir William Cornwallis’ kindly bequest to his servants.

A prominent and meticulous remembrance bequest appears in the 1637 will of Sir Francis Nedham of Barking Hall. He willed:

‘…my Executors to bestowe six poundes thirteene shillings [4] pence upon a faire communion Cup…of twentie ounces of silver…to remayne for a Remembrance of mee to the parish of Barking. About the brimme whereof on the outside to be engraven in greate Romane letters Quid retribuam Domino pro omnibus quæ retribuit mihi. And about the middle or body of the said Cupp to be written in like Romane…but of a lesser size Accipiam calicem salutaris, et agam Domino gratias reddam; And at the bottome of the Cupp in like letters as those in the midst Ex dono Francisei Nedham militis. & the day of the month when it was made’13

The communion cup, which would most likely be kept in Barking parish church, was gifted to the entire parish. Through it, every member of Barking was expected to remember the great Sir Francis Nedham. The words to go about the brim of the cup, Quid retribuam Domino pro omnibus quæ retribuit mihi, roughly translate as, ‘What shall I render to the Lord, for all the things he hath rendered unto me?’. Those destined to be etched about the middle of the cup, Accipiam calicem salutaris, et agam Domino gratias reddam, more or less translate as, ‘I will take the cup of salvation, and my Lord, I thank you’, while Ex dono Francisei Nedham militis translates as, ‘a gift from Francis Nedham, soldier’. On the one hand, it seems Nedham wished to be remembered to the parish within a godly context, having bequeathed a communion cup emblazoned with the traditional language of the Church: Latin. This was also a language out of reach of most of the population in early seventeenth-century England, and so it may have placed further emphasis on his esteemed membership of the literate class. That the communion cup was intended for widespread commemoration of Nedham within the focal point of the parish, the church, makes it likely that his ultimate desire was to be remembered as a man of prominence and influence within Barking. It was a further way in which the deferential relationship between the parish and its resident aristocrat(s) could be upheld after the latter’s demise.

In August 1670 Giles Moore highlighted the seemingly obligatory nature of remembrances when he touched on his brother’s will in his diary. In the first draft of the will, Moore grumbled, ‘there was nothing at all given to any of his kindred, nor the least mention made of them’. Moore confronted his brother about the omission after he had made sure that the room in which he lay dying was empty. Evidently it was a sensitive issue that required a hushed, but equally animated, discussion. The vicar relayed to his sibling that, while he himself did not ‘desyre or expect anything from him’, his other poorer kindred might. ‘If hee left them nothing at all for a remembrance, they would bee apt to thinke that hee had quite forgot them’, Moore concluded. Ralph Josselin felt quite forgotten in 1680 when Lady Honywood died and left him nothing to remember her by in her will. Josselin complained that they had known each other for 40 years, during which time he had been ‘serviceable every way to her for soule & body, and in her estate more then ordinery’. He seemed to believe that this entitled him to some form of ‘legacy’, a legacy that upon her death was not delivered.

Wills do not tell us when remembrances were actually given to individuals in this century, or if indeed they were given to the intended beneficiaries at all. Evidence suggests that they were sometimes handed out on the day of a person’s funeral, often doubling up as mourning accessories to be worn as a mark of respect. At the funeral of John Evelyn’s son Richard in 1658, rings were distributed to the mourners present with the motto Dominus abstulit (‘the Lord takes away’) engraved on them. Samuel Pepys had ‘wine and rings’ at the burial of Mr Russell in January 1663, surrounded by a ‘great and good company of aldermen’. Ralph Josselin targeted Lady Honywood’s funeral as part of his continued ill feeling towards her in 1680, commenting afterwards:

‘Not a glove, ribband, scutcheon, wine, beare, bisquett given at her burial but a litle mourning to servants.’14

Ralph had been unlucky. In the opening years of the eighteenth century the practice experienced by Evelyn and Pepys was as popular as ever in England, if not a little excessively executed at times. Dr Thomas Gale, who had been the Dean of York since 1697, was interred with ‘great solemnity’ in York in 1702, which included the distribution of 200 rings, gloves ‘for all’, and scarves for the bearers of his coffin. Ralph Thoresby recollected that he received his ring in a room that was so crowded it ‘could not contain the company’.

The deathbed, or the final moments before death, also saw the physical giving of remembrances in seventeenth-century England, as has already been observed. In 1635 Eleanor Evelyn gave her children rings from the deathbed, and so too Charles I, mere hours away from his execution, provided his royal offspring with rings to remember their father by. Such offerings were undoubtedly more concerned with the keeping alive of a person’s memory, or the ties of affection between individuals, than those objects that were distributed in large quantities at burials.