6.

LC–Cassock, Inc.

The decline of American disinformation in Berlin is linked to its very success, and at the heart of this story is Project LCCASSOCK—the CIA’s and Bill Harvey’s most prolific, innovative, and aggressive forgery factory, probably of the entire Cold War. For more than ten years, LCCASSOCK produced and distributed a range of high-quality magazines, newspapers, and brochures across Germany, and even in Switzerland and Austria. Its main focus was East Germany. “The principal target area is the GDR,” the CIA specified in one of around 300 archived documents, with more than 1,200 pages in total, on LCCASSOCK and its staff. The CIA used its front as an “experimental workshop” for political warfare.

Some inside the CIA began to recognize a basic problem in its approach to the ideological confrontation that was the Cold War, barely a decade after fighting had stopped in Europe: focusing on the strengths of the Soviet Union meant neglecting one’s own strengths. “Concentration on the enemy’s techniques has tended to result in the overlooking of potential psychological weapons which originate in, and are peculiar to, the free world,” the CIA wrote in one project outline.1 The driving force behind the CIA’s psychological weaponry was Karl-Heinz Marbach, the former U-boat commander.

Karl-Heinz Marbach, a decorated Wehrmacht U-boat commander, became the CIA’s principal agent for LCCASSOCK, code name for a West Berlin–based publishing organization first known as Cramer Advertisements, and later as Äquator Publishers.

(Herbert Forst)

A CIA staff officer spotted Marbach in 1950, and contacted him in the fall that year; the CIA-sponsored propaganda production under Marbach got under way in April 1952.2 By the mid-1950s, LCCASSOCK’s objective had become ambitious: to “weaken and/or destroy Communist manifestations in the GDR and the Federal Republic.”3 Large-scale forgeries were the means to this end. The physical cover for the operation was an advertisement and public relations firm, with offices at Kurfürstendamm 136, on West Berlin’s bustling main commercial avenue. The firm, Cramer Werbung, was registered with the West Berlin authorities.4

Measuring impact and making adjustments was important, so the CIA paid its front organization to “cultivate” mail correspondence with readers of its publications in Eastern Europe. LCCASSOCK included “political action efforts,” which included maintaining relationships with political activists, journalists, and academics. The CIA was also testing ongoing mail censorship procedures in East Germany and adjacent countries in the East. Cramer had a mail control office, a “customers office,” and a printing shop.

LCCASSOCK used different cover businesses over time, beginning with the ad hoc Aktionsgruppe B, then PR Cramer,5 and finally the printing house Äquator Verlag GmbH. Over the same period, Marbach’s operation evolved, in the words of one secret memo, from “a four-man ‘illegal’ show” operating from Marbach’s home to a “firm” with around thirty-five efficient employees with full tax benefits, end-of-year bonuses, security routines, and several offices.6

The falsification operations were highly specific, and required in-depth knowledge of East German affairs. To better falsify Die Volkspolizei, the in-house magazine of the GDR’s People’s Police, writers received help from the Kampfgruppe or the Free Jurists, who debriefed police defectors. The completely “black,” or unattributed, publications could be so convincingly Communist in tone that some resistance-minded distributors took issue with the “Marxist tenor” of the documents they were supposed to relay.7

The GDR did not take to disinformation lightly, and attempted to kidnap Marbach in the summer of 1952, a few months after LCCASSOCK ramped up operations. The kidnapping was foiled by Cramer’s security officer, but East Berlin authorities kept harassing Marbach. In December 1953, the same month Walter Linse was executed, the main GDR radio station “revealed” (incorrectly) that Marbach was an agent of the Gehlen organization, and even broadcast his home address.8 Meanwhile two distribution leaders were “lost” to East German security forces. Nevertheless, the CIA considered the risks of the operation low; LCCASSOCK was undeterred, and increased security along with production. LCCASSOCK even had a backup plan in the event of German tax authorities looking into the organization: the CIA disinformation front was using several wealthy former Wehrmacht colleagues of Marbach’s “as cover for the source of funds for the project,” one memo explained.9 The CIA also had plans to evacuate Marbach from Berlin in case of a Soviet invasion.

The distribution office was installed in a building separate from the editorial offices. No outsiders were permitted. “All meetings with distribution cut-outs are held outside LCCASSOCK installations,” a lengthy CIA review noted.10 The front firm hired delivery cars, and changed them frequently. Meanwhile, the pace of operations accelerated steadily. Each month the small outfit falsified an average of two different GDR publications. By early 1954, the covert PR agency had produced around thirty falsified issues of official East German publications, at least 20,000 copies in each case, adding up to approximately 600,000 items of what the CIA called “dummy issues.”11 The distribution logistics of such large amounts of paper were significant and visible, and therefore ran in a building separate from the Kurfürstendamm office. LCCASSOCK was even able to handle special debriefings: the security officer would take visitors of high value to a friend’s pub, which was equipped with a hidden tape recorder.

The list of forged publications was exhaustive. It included the main outlets with target groups across the whole society: Die Wochenpost, a popular GDR weekly; Neuer Weg, the official SED organ; Neue Zeit, the official Soviet magazine in German; Der Wegweiser, the information bulletin of East Germany’s nominal liberal party; Junge Generation, the FDJ’s official outlet; Die Tribüne, a trade union journal; Der Freie Bauer, a farmers’ publication; Die Frau von Heute, the GDR’s women’s magazine; and even Junge Welt, a well-known newspaper for a young audience.12

The CIA saw the falsified editions as particularly effective. Phony editions of existing publications could be targeted at highly specific audiences that were normally inaccessible to Western propaganda, such as the People’s Police or the FDJ, the Socialist Party’s youth organization. In addition, releasing forged magazines into the GDR presented only minimal risk to the distributors. The CIA also gleaned from field reports that forgeries, once recognized, had their own unique appeal: “duplicating exactly the format and make-up of legitimate East German publications is in itself an unusual psychological attraction to readers of LCCASSOCK publications even after their true character may have been recognized.”13

Sometimes minor details would go a long way. On June 29, 1953, just days after a major popular insurrection in East Berlin was suppressed with military force, the CIA took advantage of the general confusion. LCCASSOCK produced an official SED magazine that gave faux-official guidance: telling the workers that GDR residents wanted freedom and free elections, but also warning readers not to fight tanks with bare hands. Berlin Operations Base knew that there might be little interest in an SED booklet just after the riots—and therefore added Streng Vertraulich!, or highly confidential, to the cover. “We believe that this will enhance the appeal of the magazine to everyone and remove the stigma of party literature, since all people are interested in reading confidential material,” one CIA request for an increased forgery budget explained.14

But large-scale forgery came with unexpected repercussions. In March 1956, when distributing forged issues of Die Wochenpost, the glossy illustrated weekly, LCCASSOCK ran into problems related to legal liability for copyright and trademark infringements.15 Marbach simply changed the name to Das Illustrierte Wochenblatt.

In early 1954, BOB under Harvey was spending $60,000 per year on the forgery outfit. The organization would soon grow to thirty-two full-time German employees, several of them experienced journalists, not including freelancers who were brought in for specific projects.

By late 1956, CIA headquarters was ready to escalate its Berlin operations. In a memo that went from Germany to the head of the CIA’s Psychological and Paramilitary Staff in October of that year, LCCASSOCK’s tasks were reemphasized: the unit, just like the KgU, was to begin producing “falsifications of official East German correspondence for the purpose of administrative harassment.”16 LCCASSOCK’S tool kit kept expanding, and the front soon ventured into uncharted terrain.

Klatsch means “gossip” in German, and is also the sound of slapping somebody in the face. Klatsch is what Marbach and his team called a fake gossip magazine, planned and implemented “as a direct attack on the Nationale Volksarmee (National Peoples’ Army) and the GDR security services.” Executives in Washington wanted to ensure that Klatsch was “entertaining enough” to maintain a decent readership. The CIA was confident in its leaked and outright-invented gossip—so confident, in fact, that it even counted postal censors and “the mailman” among the publication’s target audience. Klatsch also was meant to showcase liberty itself as a “distinctly Western product,” one memo emphasized. In the Soviet bloc, BOB explained, trivia and gossip were alien to what was mainly a political and argumentative press landscape: “Klatsch is aimed at this contrast and at East German readers who, we think, particularly appreciate it.”17 Klatsch made “no claim to veracity,” but printed anecdotes in order “to inspire a chuckle, stick in the memory, and to be repeated.”18 Klatsch was mailed to 1,500 Communist Party members in East Germany.

The stories in Klatsch were wild. One, for example, claimed that Khrushchev had accused Stalin of murdering his second wife. Another claimed that scientists were on the verge of discovering a gas that would divert the continental winds—and that the Soviet Communist Party’s 20th Congress had embraced the invention, hoping to prevent balloons containing print material from being swept across the border that divided the two Germanys.19

The magazine was a success. Like the KGB and the Stasi and even MI6 before it, the CIA was quick to grasp the time-tested recipe of tabloid success: “many pictures, short texts, features, a touch of sex, and a tendency towards sensationalism.”

LCCASSOCK even ventured into prophecy. Astrology, though not particularly fashionable in the West, gained political significance when transplanted into the Soviet bloc. As Harvey’s Berlin outpost noted, astrology was much more popular in Germany than in the United States; most major German magazines regularly carried horoscopes, usually printed next to the crossword puzzle. Yet this high popular demand for astrology was subdued in the East, where seeking truth in the stars was incompatible with “the precision of dialectic materialism,” as Berlin Operations Base noted. This created an opening for covert operations. LCCASSOCK published an astrological magazine, called Horizont, and Berlin Operations Base explained to Washington that the publication was conceived as “a direct attack on advocates of Moscow Communism through the vehicle of astrological analysis and prophecy.”

Measuring performance was crucial for follow-on funding from the CIA, so the front produced an array of accounting figures to show how valuable it was. LCCASSOCK, like the KgU, reached peak performance in 1957. The disinformation front produced and published 855,969 media items that year, almost twice the number of items produced in 1956.20 The front’s average monthly output was an impressive 71,300 media items. The boost in operational capacity became possible because LCCASSOCK’s own, CIA-funded, low-cost printing plant became operational that year. At the same time, LCCASSOCK expanded its mailing lists. It mailed 651,917 media items to recipients in East Germany in 1957. By September 1958, the list included more than 42,000 addresses. One way to measure effect was by counting the number of correspondents. CIA’s disinformation mill had received responses from 2,074 recipients; “at present the ratio is 20:1,” BOB wrote in September 1958. About 13 percent of Äquator’s 1957 media output, 114,033 items, was distributed in Soviet bloc countries other than the GDR (and Russia)—“satellite countries,” in Cold War jargon. By fall 1958, the number of non-GDR correspondents was 721. The most favorable responses came from Polish recipients, followed by Czechs, Romanians, Russians, and Bulgarians.21

In early September 1957, just weeks before the USSR’s launch of Sputnik, LCCASSOCK prepared a series of letters with personalized horoscopes for officials in the Ministry of State Security. The letters were mailed to pro-regime Berlin residents in the expectation that the collaborators would pass on the odd horoscopes to the actual targets in the MfS. Hans Fruck, the new deputy head of the Stasi’s foreign intelligence arm, HVA, was targeted with eerie horoscopes predicting his doom. “These actions were designed to introduce a note of uncertainty within the MfS bureaucracy and, perhaps, to mislead MfS investigative energies,” BOB reported back to Washington. The CIA base knew that the phony horoscopes were getting through to their MfS targets, but the results were unclear.22

Nevertheless, the CIA stuck to the horoscope tactic, and even upped the ante. In June 1958, LCCASSOCK prepared “400 horoscope harassment letters” for selected Socialist Party (SED) and Stasi personalities. The letters, ostensibly prepared by a nonexistent astrological research institute in West Germany, were designed to exploit an opening rift among members of the SED’s central committee, notably between Fritz Selbmann and Walter Ulbricht, two influential Socialists: each letter contained “a carefully written horoscope analysis of the status and future of Fritz Selbmann, particularly in his relationship to Ulbricht.” The goal of the operation was to bolster Selbmann’s prestige at a time when his internal opposition was at a high point ahead of the SED’s fifth major convention, a major, highly choreographed political rally with the motto Socialism Is Winning. Even Nikita Khrushchev attended. Russia was leading the space race, and for a brief moment the GDR thought it could compete with—or even outdo—the West German economic miracle of the postwar years. Guided by two case officers, Marbach’s team produced 662 copies of a forged “black” letter to party members, printed on original letterhead from an SED-linked anti-Fascist association of political opponents of Nazi Germany.

The goal was to drive a wedge between the Communist old guard and the new and more opportunistic SED factions supporting Ulbricht. A collaborator of Marbach’s wrote the forgery “in an appropriate ‘anti-fa’ tone and with a view to creating a maximum divisive effect,” as BOB reported back to headquarters a few months later. The 662 fake letters were sent to Antifa activists, Socialist Party members, to the party’s Central Committee, and to editors at East German newspapers just prior to the opening of the GDR Party Congress.23

The political warfare planners at Berlin Operations Base were careful to manage expectations at CIA headquarters. The disinformation campaign that Marbach and his team were designing and implementing was counterintuitive, neither wide nor narrow, designed neither for mass influence nor targeting of individuals. Instead, the Berlin base saw LCCASSOCK’s operations as “specific influence,” which was in theory more concentrated than mass media operations but less concerned with direct individual reactions. This unusual format meant that evaluating operational effectiveness was equally unusual: “The criteria of LCCASSOCK effectiveness should accordingly be more exacting than those employed in mass influence operations and less demanding than those required by singleton actions.”

A secret CIA memo from September 1958, from William Harvey at Berlin Operations Base to the Eastern European Division at CIA headquarters, discussing anti-Stasi disinformation operations (CIA)

As one officer reported in a secret memo, signed off by Harvey, “I feel that LCCASSOCK, because we have used it as a kind of psychological warfare workshop to test ideas and to experiment, has as a result developed a body of thinking which has already proved useful and will be increasingly so in the future.” The CIA’s Berlin-based “experimental workshop” attempted to identify and analyze population attitudes and mental responses, the officer went on, and its approach “approximated that of a psychologist with his patients.” The experiments had demonstrated that “an indirect approach,” exemplified by the front’s forays in astrology, gossip, rumor, and women’s magazines, worked best to get into the mind of the target. The approach was tailored to Communist society, where individuals would have a hard time reconciling their past experiences and expectations with the harsh realities of everyday life—hence the temptation to escape from this reality into “superstition and fantasy.”

Schlagzeug, published by Äquator, was Germany’s most significant jazz magazine in the mid-1950s. The CIA first funded the magazine, then attempted to spin it out as a for-profit publication.

In late 1958, Harvey signed off on a memo to the chief of the Eastern European Division that would hasten the end of LCCASSOCK. Over 15 pages, classified as secret, the memo discussed the commercial viability of a jazz magazine. The first issue of Schlagzeug had been published in September 1956. “Along with astrology, we consider [jazz] one of the most potent psychological forces available to the West for an attack on Moscow Communism,” Harvey argued.24 The reader response to the publication of Schlagzeug’s first issue was unprecedented. The CIA front received one written reaction, “including a number from FDJ Chapters,”25 for every 88 copies. The jazz magazine was frequently shared hand-to-hand at FDJ meeting places and dance halls, U.S. intelligence officers believed. Harvey and his propaganda team considered Schlagzeug one of their most effective covert publications, and the one “most susceptible to further development and expansion.”

The music magazine soon absorbed more than 10 percent of the front firm’s time and resources. It was professionally produced, often featuring African American jazz icons like Ella Fitzgerald and Sidney Bechet on the cover, with black-and-white pictures and a new pop-art coloration each month. One or two articles per issue were subtly subversive. One July 1959 piece highlighted the visit of international jazz legends to Berlin despite Soviet resistance—pictures showed Louis Armstrong enjoying a sausage and beer as he chatted with Willy Brandt, then Berlin’s mayor, or Art Farmer and Gerry Mulligan, cool bebop stars, visiting the sunny Brandenburg Gate in sports jackets and shades, drab East Berlin at their backs. The magazine wasn’t blatantly pro-capitalist; it wanted to be edgy and bohemian. One editorial highlighted the rebellious character of jazz, comparing the music to subversive art like Dadaism.26 For the most part, however, the magazine was just about jazz, and was mainly distributed in West Germany; only minor quantities went to the GDR.

In May 1956, a “strong Schlagzeug delegation” attended a jazz festival in Frankfurt am Main, and the head of LCCASSOCK’s distribution operation continued on to Austria and Switzerland to set up outlets through magazine sales agencies and concert halls. The magazine, per BOB’s summary, had matured into “an attractive, informative, and technically responsible journal of jazz.” Schlagzeug represented an all-German approach to jazz, the memo argued, “thereby maintaining, incidentally, its usefulness as a KUCAGE medium for Soviet bloc consumption” (KUCAGE was a cover name for the CIA’s psychological and paramilitary operations staff). Never mind its paramilitary backers and its ex-Wehrmacht chief: the jazz magazine had “gradually come to be recognized by jazz experts and fans alike as the best journal of its kind presently appearing in Germany,” the BOB memo boasted, adding that Schlagzeug was now fully accredited by the West German Jazz Federation. The Berlin station pointed out to Langley that more than 20,000 fans had paid to hear Benny Goodman in Berlin during a recent show in May,27 and concluded that the jazz cover for its disinformation front had a bright future: “Our suspicion [is] that the jazz movement in Germany and in Europe generally is not only much more intense, more pervasive and popular, but is more profitable than in the United States.”

Schlagzeug covers, featuring jazz legends from the September, July, and November 1959 issues

The problem was that the numbers did not check out. By 1958, LCCASSOCK had become a noteworthy cost item. Although financial details are mostly redacted from the files, the figures become clear through careful reading: the average monthly costs of the entire LCCASSOCK operation from March to June 1958 were DM 35,687, plus total monthly salaries of DM 19,516.28 The budget included a number of perks for the CIA’s unwitting German employees at Äquator: union scale increases; promotions; travel, rent, and utilities; a yearly round-trip flight to West Germany; and “operational entertainment for contacts for political action.”29 In 1958, the CIA’s covert action objective changed and the Agency significantly cut its support for LCCASSOCK, which then amounted to three-quarters of the front firm’s budget. By mid-1959, despite the jazz-generated income, the monthly salary costs covered by the CIA still averaged $5,000.30 BOB operatives may have dreamed of turning their beloved jazz magazine into a profitable start-up cover for even more aggressive operations, but in reality, their love of jazz helped bring down one of the most aggressive covert ops of the Cold War.

The publication of Die Frau, LCCASSOCK’s women’s magazine, backfired in a similar fashion. Throughout 1956, Marbach’s outfit produced three issues of the magazine, printing 20,000 copies each time. The first issue that year had a famous pro-Western Russian ballet dancer on the cover, Tatjana Gsovsky. One story presented modernist mid-century interior design as a form of protest against “attacks against privacy.”31 The spy base, under the gun-toting Harvey, even produced a “pony edition” of Die Frau, at a cost of DM 9,470, and mailed almost ten thousand copies with pictures of ponies into the Soviet zone. As of January 1957, the covert editors of Die Frau were in active mail correspondence with 185 women in the Soviet bloc.32

The covert action specialists in Washington did not appreciate Die Frau.33 One reviewer assessed that it was “an attractive publication which certainly entertained our secretaries here,” yet pointed out that it was “in no way different, better, or prettier” than other women’s magazines. The reviewer saw it as a “questionable” publication, with unclear tactical benefit. The reviewers were similarly skeptical about LCCASSOCK’s dating service, the Von Herz zu Herz newsletter, a monthly publication that also peaked in 1956. “We fail to understand the purpose behind the lonely hearts leaflet,” one reviewer wrote.34 Die Frau first led CIA reviewers to question the impact and rationale of LCCASSOCK’s “marginal” publications. Jazz, fashion, and love, it turned out, were too indirect an approach to winning the Cold War. By mid-1957, the overly experimental political warfare workshop in Berlin was slowly falling out of favor.

The CIA changed its covert action objectives in 1958, cutting back financial support for and reorganizing its Berlin front organizations.35 On November 29, a Saturday, the BOB case officer went over to Galvanistrasse to discuss two upcoming “black letter” operations, one directed against a Chinese commune, the other a local Party chapter. But that afternoon, Marbach objected. He argued that Äquator Verlag had matured into a well-reputed and respectable publishing business, and could no longer afford to indulge in “dirty” spy operations.

Die Frau was a CIA-funded women’s fashion and home-decorating magazine published by Marbach.

(Clint Montgomery)

“There is some merit in this argument,” the CIA case officer conceded. But he pushed back against Marbach, arguing that surely an operation could be compartmentalized and run in a way that would not inflict reputational harm on the publisher. Marbach objected again, arguing that black ops were bad, per se, and “inappropriate to the present Cold War situation.” The case officer departed in a rage. “Who in the last analysis is running LCCASSOCK—we or L-1?” he asked in his report, referring to Marbach by his informal cover name. The former Wehrmacht officer, the CIA officer complained, “is the product of a long KUBARK handling policy which led him to believe that he is a completely free agent who happens of his own free will to be cooperating with us,” he wrote, using one of the CIA’s vintage cryptonyms for itself. The case officer found it hard to believe that Marbach would not yield, “despite the money we’ve poured into the project,” and despite “our quite obvious legal ownership” of 76 percent of the Äquator publishing house. “In my opinion this ‘alice-in-wonderland’ kind of relationship with L-1 cannot go on much longer,” he wrote. The case officer was so angry that he confessed a personal antipathy to Marbach, and called him an “intellectually shallow person.”36

The CIA front LCCASSOCK pioneered a tactic later frequently adopted by Eastern bloc intelligence: exposing the Nazi past of German politicians in order to compromise or topple them.

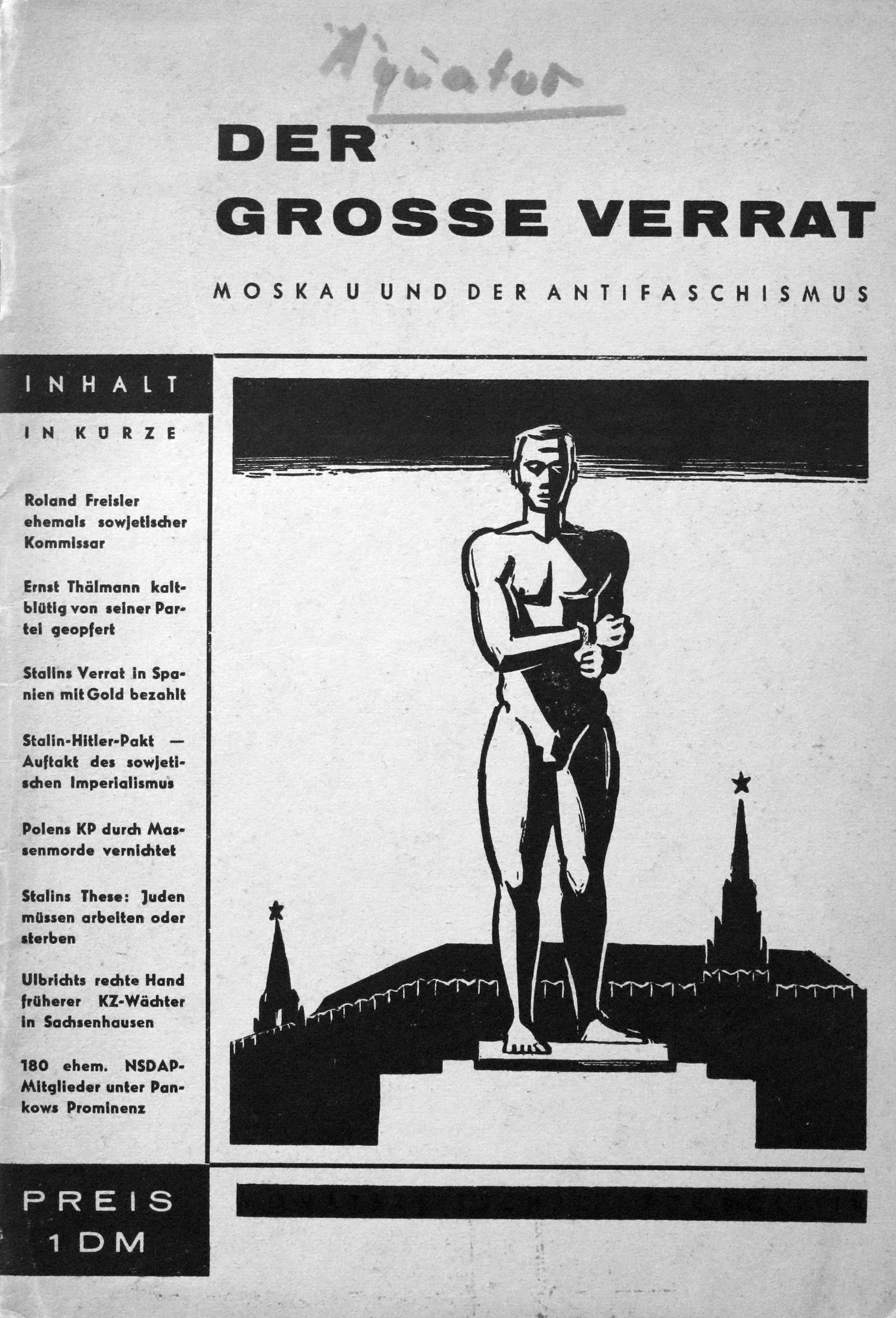

One of Äquator Verlag’s most aggressive operations took place after Marbach had articulated his displeasure, and after the CIA had already decided to liquidate. In May 1959, LCCASSOCK published a 32-page booklet entitled “The Great Betrayal. Moscow and Anti-Fascism.”37 The collection of ten articles argued that once the veil of institutional anti-fascism was lifted, communism in fact had been aiding and abetting fascism again and again, in the Hitler-Stalin Pact, for instance. Most notably, the pamphlet leaked the names of 180 prominent politicians, business leaders, and scientists in the GDR who had been members of the National Socialist Party during the Third Reich. The list included titles, full names, NSDAP entry dates, and membership numbers. Fifty-two members of the new East Berlin Parliament had been former Nazis. Three East German MPs had been members of the SS, and one even part of Adolf Hitler’s elite personal guard unit. The booklet did not name its editor or authors, and it gave only one source for the list of names: the investigative committee of the Free Jurists, aka CADROIT.

The CIA phased out operations by January 1, 1960, and then legally terminated LCCASSOCK on May 31, 1961, after a lengthy eighteen-month liquidation process.38 Marbach went on to work for West Germany’s still young foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst, or BND, but quickly fell out of favor for breaching security protocol. He continued his career at the German Ministry of Defense.