9

Creativity and Psychopathology: Shared Neurocognitive Vulnerabilities

John Forbes Nash, Robert Schumann, and William Blake suffered from delusions and hallucinations (Bentley, 2001; Nasar, 1998; Ostwald, 1985). Virginia Woolf, Hart Crane, and Vincent van Gogh committed suicide during episodes of depression (Meaker, 1964). Ernest Hemingway, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and William Faulkner were acknowledged alcoholics (Dardis, 1989; Frey, 1994). These are just a few of a large number of examples of creative luminaries who appear to have suffered from severe, and in all too many cases life-ending, forms of mental illness. Are these examples merely coincidental, or do they represent an actual underlying relationship between creativity and madness?

The benefits of creativity have been well documented: not only do creative innovations contribute to our survival as a species, but art, music, literature, and scientific advances add comfort and ease to daily living and enrich the human experience at both the individual and societal levels. The costs of mental illness, in terms of financial burden and human suffering, have likewise been well documented—both for the individual and for society (World Health Organization, 2001). If there is, in fact, a connection between creativity and mental illness, then understanding the nature of that connection may have broad implications in terms of the treatment of mental disorders and in the development of strategies for enhancing creative thought and accomplishment that can enrich all of humankind.

In this chapter, I will review the evidence for a creativity-psychopathology connection. I will also review several models that could account for this association. Finally, I will support a “shared neurocognitive vulnerability” model of creativity and psychopathology (Carson, 2011), in which creative ideation shares genetically influenced neurocognitive features with certain forms of mental illness. These features may manifest themselves as severe psychopathology or as creative ability, depending on the presence or absence of additional cognitive factors that act to protect the individual from the most severe consequences of mental disorder.

Creativity and Mental Illness: Is There a Relationship?

Creativity is defined as an idea or product that is both novel or original and useful or adaptive in some way (Barron, 1969). Creative capacity has long been considered an advantage for humans, both at the level of the species and at the level of the individual. At the level of the species, creative ideation and behavior allow for adaptation to a changing environment and hence improved survival odds (Richards, 1999). At the level of the individual, creativity has been viewed as a facet of self-actualization (Rogers, 1961) and the expression of a fulfilled life (Maslow, 1970). It has been correlated with positive personality traits such as openness to experience and self-confidence (Feist, 1999). Creativity is also a highly valued personal trait. Besides the traditional creative fields, such as art, writing, music, and science, creativity is one of the most sought-after traits in business (Matthew, 2009), with many of the world’s most prestigious business schools offering courses in creativity (Gangemi, 2006). Because creativity is so valuable, some psychologists suggest that creative accomplishment may serve as a “fitness indicator,” increasing the sexual attractiveness and mating proficiency of creative individuals (Miller, 2001). In fact, studies have shown that individuals deemed creative have more sexual partners than those deemed less creative (Nettle & Clegg, 2006) and are rated as highly desirable potential mates (Buss & Barnes, 1986).

Yet despite the value of creativity at the personal and societal level, the tendency for creative individuals to suffer from what we would now call mental illness has been noted for thousands of years. Plato, for example, remarked that poets, philosophers, and dramatists had a tendency to suffer from “divine madness,” one of the four types of madness cataloged in his Phaedrus (Plato, 360 B.C.). And Aristotle was the first to note a tendency for creative individuals to suffer from depression, as he asked in “Problem XXX” why it is that men who have become outstanding in poetry and the arts tend to be melancholic (Aristotle, 1984). The high rate of substance abuse and alcoholism in creative individuals, especially writers and poets, was noted in the early literature as well; over two thousand years ago, the Roman poet Horace wrote: “No poems can please for long or live that are written by water drinkers” (as cited in Goodwin, 1992, p. 425). The view of the mad creative genius was furthered by the moody personality and bizarre behavior of Renaissance artists like Michelangelo (Condivi, ca. 1520/1999) and the Romantic poets (Becker, 2001). For example, Shelley suffered from hallucinations and debilitating bouts of depression, and Byron exhibited erratic mood fluctuations that ran from suicidal melancholia to extreme irritability and expansiveness (Jamison, 1993).

In the mid-twentieth century, empirical evidence for the connection between creativity and psychopathology began to emerge. In a study that examined the adopted-away offspring of mothers with and without schizophrenia, Heston (1966) found that the children of mothers with schizophrenia were more likely to hold creative jobs and have colorful lives than were the offspring of mothers without schizophrenia. Then, in a study that examined male Icelanders born between 1881 and 1910, Karlsson (1970) discovered that individuals with a psychotic relative were almost three times more likely to be registered in Who’s Who for excellence in a creative field (scholars, novelists, poets, painters, composers, and performers) than those without a psychotic relative. He suggested that having a predisposition to schizophrenia might confer a creative advantage and concluded that “some type of mental stimulation is associated with a genetic relationship to psychotic persons” (p. 180).

These findings prompted a new generation of researchers, beginning in the late 1980s, to examine the incidence of psychopathology within the population of highly creative achievers. The results of this research support a higher risk for three categories of disorders among creative individuals: mood disorders (especially bipolar disorders), schizospectrum disorders (psychosis proneness), and substance abuse disorders. In addition, several recent studies have begun to investigate the association between creativity and the relatively new diagnosis of ADHD (Abraham, Windmann, Siefen, Daum, & Gunturkun, 2006; Cramond, 1994; White & Shah, 2006). Because the evidence for the ADHD-creativity association is not clearly established, I will limit this review to the three categories of disorders that have been more thoroughly investigated.

Creativity and Mood Disorders

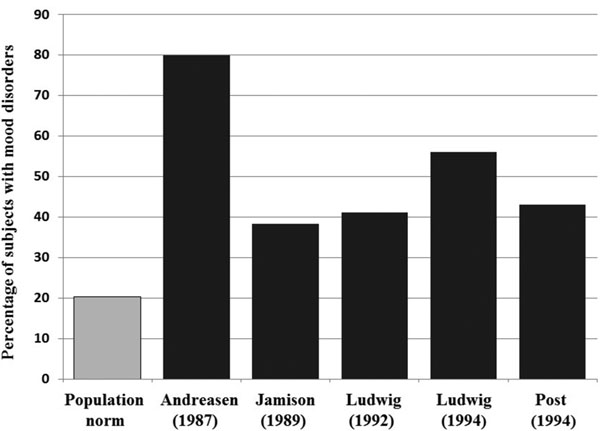

The first study credited with using modern diagnostic methods to examine the creativity-psychopathology connection was conducted by noted schizophrenia researcher Nancy Andreasen (1987). Andreasen conducted diagnostic interviews with thirty writers from the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop and their first-degree relatives and compared them to a matched control group. Based on the earlier Heston (1966) and Karlsson (1970) studies, Andreasen had expected to find a higher incidence of schizophrenia among the writers and their relatives. However, no incidents of schizophrenia were found in either the writers or the controls. Instead, she found that 80 percent of the writers suffered from a mood disorder, and that the writers were four times more likely to suffer from bipolar disorder than the controls. Andreasen also found that both mood disorders and creative interests tended to run in families, suggesting that “affective disorder may be both a ‘hereditary taint’ and a hereditary gift” (Andreasen, 1987, p. 1292).

Two years later, Jamison (1989) procured detailed information about mental illness, mood disorders, and creative productivity from forty-seven award-winning artists and poets from the UK. She found that an unusually high percentage of her subjects (38.3%) had been treated for mood disorder, especially bipolar disorder (6.4%). Poets (55.2%) and novelists (62.5%) had the highest rates of treatment for all types of mood disorders. She further reported that rates of creative productivity seemed to be associated with upswings in mood in both the disordered and nondisordered writers and artists. Jamison (1989) suggested that these upswings increased activation of associational networks and enhanced sensory experience, both of which are important for creativity. These findings are in line with other research that indicates that upswings in positive emotion are associated with increased expansive ideation and divergent thinking (see Ashby, Isen, & Turken, 1999, for a review).

In a subsequent study, Ludwig (1994) compared the psychiatric symptoms of fifty-nine female writers in the University of Kentucky National Women Writer’s Conference with those of controls matched for age and education. The symptoms were evaluated through screenings and personal interviews using DSM III-R criteria. Rates of both depression (56%) and mania (19%) in the writers were significantly higher than in the controls.

In addition to research that examined mood disorders in living artists and writers, two studies examined mood symptoms in deceased creative luminaries, based on available biographical sources. Post (1994) studied the lives of 291 world-famous men from assorted creative professional categories and suggested psychiatric diagnoses where appropriate based on DSM III-R criteria. Using general population demographics as controls, Post found that the creative subjects in all professional categories demonstrated higher rates of mood disorder, but rates were particularly high in writers. Ludwig (1992, 1995) acquired psychiatric data from more than 1,000 deceased luminaries whose biographies had been reviewed by the New York Times Book Review between 1960 and 1990. He found significantly higher rates of psychopathology, including mood disorders, among persons in the creative arts (artists, musical composers and performers, and writers) than among those luminaries in other professions.

Figure 9.1

Percentage of creative individuals with mood disorder compared to population norms across studies. Population norm taken from Kessler et al. (2005).

While these empirical studies suggest that people in creative professions (especially professions affiliated with the arts) tend to display higher rates of affective psychopathology than the norm, severe forms of affective illness may interfere with creativity. For example, writers from Andreasen’s (1987) Writers Workshop study reported anecdotally that depressive episodes interfered with cognitive fluency and energy, while manic episodes led to distractibility and disorganization; both interfered with the ability to work effectively (Andreasen, 2008). Empirical evidence for the connection between creativity and the degree of affective dysfunction was provided by researchers from Harvard and Denmark (Richards, Kinney, Lunde, Benet, & Merzel, 1988). They found that subjects with cyclothymia and the first-degree relatives of subjects with manic depression had higher levels of creative accomplishment and interest than either nondisordered controls or the manic depressive subjects themselves. These authors concluded that either hereditary risk for manic depression or milder variations of bipolar pathology may enhance creativity, but that full-blown manifestations of bipolar illness may interfere with creative activity. This set of conclusions suggests an inverted “U” hypothesis relating creativity to psychopathology (Richards et al., 1988).

In general, the empirical research on creativity and mood disorders suggests (1) that creative individuals may carry a risk for affective psychopathology, especially bipolar disorder, that is greater than that of the general public (Andreasen, 1987; Jamison, 1989; Ludwig, 1992; 1994, 1995); (2) that genetic risk for (or mild forms of) affective pathology is more beneficial for creative accomplishment than more severe forms of illness (Andreasen, 2008; Richards et al., 1988); (3) that creativity and mood disorders appear to run in families (Andreasen, 1987; Jamison, 1993); and (4) that shifts in mental states associated with mood (moving toward a more positive valence) may facilitate creativity (Ashby et al., 1999; Jamison, 1989).

Creativity and Schizospectrum Disorders

Nobel Prize winner John Forbes Nash was once asked by Harvard mathematician George Mackey how he could believe that aliens from outer space had recruited him to save the world. He responded, “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously” (quoted in Nasar, 1998, p. 11). Nash, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, suffered from delusions and hallucinations. His response to Mackey suggests delusional ideas may share a common element with at least some creative insights.

There is a rich literature describing psychotic and odd or eccentric behavior in creative individuals. William Blake, for example, appears to have had hallucinations since childhood; he believed that an etching technique he developed was provided to him by his dead brother, Robert, and that many of his poems and paintings were channeled to him through spirits (Galvin, 2004). The composer Robert Schumann suffered from hallucinations and delusions, and believed that Beethoven and Mendelssohn were channeling musical compositions to him from their tombs (Jensen, 2001; Lombroso, 1891/1976). Nikola Tesla, the scientist credited with discovering alternating current, suffered from auditory and visual hallucinations, including a perceived love affair with a pigeon (Pickover, 1998).

Besides anecdotal reports from the biographies of creative luminaries, studies of creative achievers at Berkeley’s Institute for Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR), renowned for its groundbreaking work on creativity and personality in the 1950s and ’60s, found that creative writers and creative architects had elevated scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) scales of schizophrenia and paranoia (Barron, 1955; MacKinnon, 1962). Both creative writers and architects also reported frequent unusual perceptual occurrences and odd mystical experiences (Barron, 1969). Around the same time, a series of studies by Cattell and Drevdahl found that scientists, creative writers, and artists all scored higher on the personality measure “schizothymia” than did the presumably less creative control groups (Cattell & Drevdahl, 1955; Drevdahl & Cattell, 1958). These researchers also noted that while schizothymia was negatively correlated with self-sufficiency (a measure of good mental health) in the normal population, both schizothymia and self-sufficiency characterized their creative groups. These findings are an early indicator of the shared vulnerabilities model of creativity and psychopathology.

In the late 1970s, Robert Prentky (1979) suggested a theory that both persons with schizophrenia and highly creative persons might share a common cognitive style, namely, a style of accepting a broad bandwidth of information and processing it at a relatively shallow level of analysis, rather than focusing on a more limited volume of information and conducting detailed analysis. Evidence for this theory was provided by Dykes and McGhie (1976), who reported that creative individuals and subjects with schizophrenia tended to process auditory information in a similar manner in a dichotic listening task. Keefe and Magaro (1980) found that a group of subjects diagnosed with nonparanoid schizophrenia scored higher on two measures of a divergent thinking task than did a group of normal controls. They concluded that creative and schizophrenic individuals may share a style of thinking that has been called loose (Maher, 1972) or overinclusive (Andreasen & Powers, 1975).

However, displaying a loose cognitive style and scoring high on divergent thinking tasks is not the equivalent of accomplishing works of creativity. Researchers and creative achievers alike seem to be in agreement that meaningful creative work is difficult, if not impossible, during active episodes of schizophrenia; in the case of John Forbes Nash, his Nobel Prize–winning work was accomplished before he received the diagnosis of schizophrenia (Nasar, 1998), and the creative writers and architects in the IPAR studies had elevated scores on schizophrenia and paranoid MMPI scales rather than actual schizophrenia diagnoses. Creative individuals are more likely to exhibit subclinical traits related to psychosis rather than actual psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia (Brod, 1987; Claridge, 1997).

Schizotypal personality—or schizotypy—is considered to be a subclinical indicator of a predisposition to psychosis; it exists on a continuum between normal experience and schizophrenia (see Claridge, 1997). A body of research has found an association between schizotypy and creativity (Brod, 1987; Cox & Leon, 1999; Green & Williams, 1999; Poreh, Whitman, & Ross, 1994; Schuldberg, French, Stone, & Heberle, 1988). Both Brod (1987) and Prentky (1989) examined research on the connection between creativity and schizotypy/psychosis-proneness and concluded that creative persons tend to occupy a space somewhere in the midrange on the continuum between normalcy and schizophrenia. Prentky (2000–2001, p. 99) suggests that because creative individuals live “closer to the fringes of deviation, there may be a higher incidence of psychopathology among this group.”

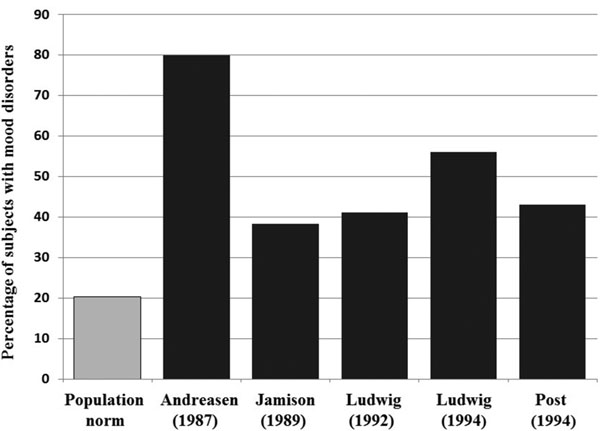

More recent studies have examined the schizotypy-creativity connection, making the distinction between positive and negative schizotypy. Positive schizotypy, or psychosis-proneness, is characterized by unusual perceptual experiences (distortions in perception, such as hearing voices in the wind) and magical thinking (fanciful ideas or paranormal beliefs, such as belief in telepathy or omens). These characteristics can be viewed as subclinical associates of hallucinations and delusions, or the positive signs of schizophrenia. Negative schizotypy is characterized by social anhedonia (lack of desire or pleasure in socializing with others) and cognitive disorganization (difficulties in attention, concentration, and decision making). These characteristics can be viewed as subclinical associates of the negative signs of schizophrenia (Mason & Claridge, 2006).

Studies by two separate research groups compared British art students to students in non-arts disciplines, finding that art students scored significantly higher than the control groups on measures of positive but not negative schizotypal traits (Burch, Pavelis, Hemsley, & Corr, 2006; O’Reilly, Dunbar, & Bentall, 2001). Nelson and Rawlings (2010) found that positive schizotypy was also associated with increased phenomenological experience of creativity in a sample of one hundred artists. Other studies indicate that positive and negative schizotypal traits may differentiate types of creative individuals. Nettle (2006) reported that poets and artists, along with psychiatric patients, had elevated levels of positive schizotypal traits, while mathematicians had higher levels of negative schizotypal traits. Along similar lines, Rawlings and Locarnini (2008) found that professional artists and musicians scored higher on measures of positive schizotypy and hypomania than biologists and mathematicians, who scored higher on many of the symptoms related to negative schizotypy. These findings are in accord with research from our Harvard lab, in which high achievers in the fields of art, music, and creative writing demonstrated significantly higher positive schizotypy scores than low achievers in those fields who were matched for IQ. High achievers in scientific fields, however, did not demonstrate higher positive schizotypy (Carson, 2001). In sum, the results of these studies suggest that individuals in fine arts fields (artists, writers, and musicians) may have a pattern of elevated predisposition to psychosis, while scientists do not tend to show this pattern.

Figure 9.2

Positive schizotypy (as measured by Unusual Experiences Scale) in creative individuals compared to population norms across studies. Unusual experiences subscale of the O-LIFE and population norm taken from Mason and Claridge (2006).

The “inverted U” pattern of creativity and psychopathology noted with bipolar patients (Richards et al., 1988), in which milder subclinical forms of the illness were associated with higher levels of creativity, was replicated using subjects with schizospectrum symptoms. Kinney et al. (2000–2001) found that schizospectrum traits tend to run in families. They also found that peak creativity levels were higher in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder or two schizotypy signs (such as magical ideation or illusion experiences) than in subjects with no schizotypal signs or with full-blown schizophrenia.

In general, research on schizospectrum pathology and creativity supports two conclusions: (1) there is an elevated level of schizotypy and psychosis-proneness in divergent thinkers and creative individuals (e.g., Brod, 1987; Burch et al., 2006; Schuldberg et al., 1988), and (2) milder symptom sets are more conducive to creativity than more severe forms of the schizospectrum disorders (Kinney et al., 2000–2001), as is the case with bipolar spectrum disorders.

Creativity and Alcoholism

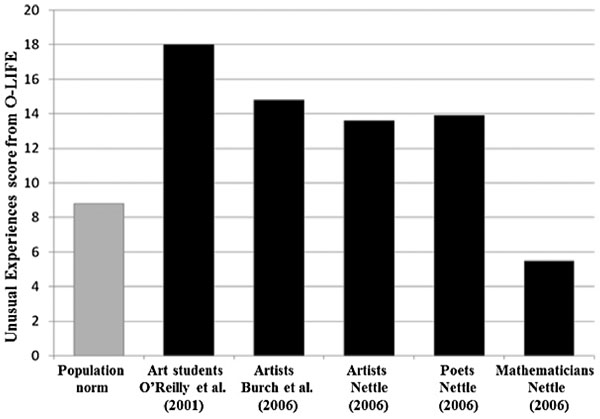

Creative luminaries have long used alcohol and other psychoactive drugs as a method of summoning the muse. Aristophanes referred to the connection between cleverness and wine consumption (Aristophanes, 424 b.c.), suggesting that even two thousand years ago creative inspiration was associated with wine consumption. More recently, novelist William Styron described alcohol as “the magical conduit to fantasy and euphoria, and to the enhancement of the imagination” (Styron, 1990, p. 40). The implicit assumption is that alcohol consumption is related to creative output (Ludwig, 1990). Research on creativity and alcoholism does indeed indicate a greater prevalence of alcoholism among creative groups than in the general population (Andreasen, 1987; Dardis, 1989; Ludwig, 1992; Post, 1994).

Andreasen (1987) found that 30 percent of the writers in the Iowa Writers Workshop suffered from alcoholism, compared to 7 percent from the control group. Post (1994) found that 14 percent of the writers, composers, and artists in his biographical review of famous men met diagnostic criteria for alcoholism. This is about twice the rate that is found in the general public (Kessler, 2005). Ludwig (1992) also reported an elevated mean level of alcohol abuse among artists (22%), composers (21%), musical performers (40%), actors (60%), fiction writers (37%), and poets (30%), but lower than normal rates (1–2%) among natural scientists. Levels of alcoholism and alcohol abuse seem to be particularly elevated among fiction writers. Of the eight American novelists who have won the Nobel Prize, five have been alcoholics (Dardis, 1989).

Figure 9.3

Percentage of creative individuals with alcoholism compared to population norms across studies. Population norm taken from Kessler et al. (2005).

As with other disorders, it appears that there is an “inverted U” association between alcoholism and creativity (Dardis, 1989; Ludwig, 1990). Biographical information from the lives of famous writers such as Hemingway, Poe, and Fitzgerald indicates that while heavy drinking and creative production went hand in hand early their careers, progressive alcoholism diminished both the quality and quantity of later creative writing (Dardis, 1989). Although creative individuals may believe that drinking inspires creativity, full-blown alcoholism appears to be detrimental to creative efforts. In a review of the effects of alcohol on the creative production of thirty-four heavy-drinking artists, writers, and composers, Ludwig (1990) found that 59 percent of the sample believed that alcohol facilitated their creativity either directly or indirectly during the early phases of their drinking. However, ultimately, 75 percent of the sample believed that alcohol had a direct negative effect on their work, especially in the later phases of their drinking careers.

Rates of alcoholism are elevated not only among creative individuals but among the bipolar and the schizospectrum populations as well (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 1995). A predisposition to alcoholism in creative groups as well as in groups that demonstrate forms of psychopathology related to creativity suggests an underlying shared vulnerability.

Models of the Interface between Creativity and Psychopathology

The research reviewed thus far suggests that there is both anecdotal and empirical evidence to support an elevated risk for psychopathology, especially mood disorders, schizospectrum disorders, and alcohol-related disorders, among creative individuals.

While research has persuasively indicated an association between psychopathology and creativity, the nature of the association is less clear. Several models have been proposed to account for the higher incidence of certain forms of psychopathology among highly creative individuals (e.g., Becker, 2001; Richards, 1990). Becker (2001), for example, has suggested that there is a social expectation that creative people will act in bizarre and unconventional ways, and that, by demonstrating symptoms of psychopathology, creative people are merely acting out the part that society has assigned them. Alternately, a “social drift” model suggests that individuals with mood disorders, alcohol problems, or psychotic tendencies do not do well in ordinary nine-to-five business routines and thus may be drawn to creative professions, such as art, writing, or music, which are unsupervised and lack rule-based expectations (Ludwig, 1995). Yet another model suggests that creative individuals may have historically been labeled as “mentally ill” in order to silence their innovative ideas and maintain the status quo.

These sociocultural models may explain some portion of the overlap between creativity and psychopathology. However, anecdotal reports (e.g., Nasar, 1998), family and adoption studies (e.g., Heston, 1966; Karlsson, 1970), as well as neuroimaging (e.g., de Manzano, Cervenka, Karabanov, Farde, & Ullén, 2010) and molecular genetic studies (e.g., Kéri, 2009) suggest that the relationship between creativity and psychopathology is not primarily sociocultural in nature. I will describe three additional models that address the creativity-psychopathology relationship at a finer-grained level of analysis.

Model 1: Creative Activity Causes (or Enhances) Mental Illness

Is there something about creativity or creative activity that could increase the risk for mental illness? Anecdotal evidence, especially from creative writers, supports such a model. For example, Hemingway suggested that creative work could be a factor in the development of depression. He wrote in his acceptance speech for the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, “Writing, at its best, is a lonely life . . . if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day” (Hemingway, 1954, para. 4). Schildkraut, Hirshfeld, and Murphy (1994) studied abstract expressionist artists of the New York school, a number of whom suffered from depression and ultimately committed suicide. Schildkraut and colleagues noted, in line with Hemingway, that artists and writers must deal on a daily basis with the existential themes of the plight of man. This constant exposure to the themes of aloneness, the futility of life, and the “raw suffering of human existence” may augment depression and despair (Schildkraut et al., 1994, p. 486).

Another possible influence of creativity on psychopathology involves the stigma of being different and bucking the system, qualities that are part and parcel of creative work. Richards (1990) suggests that the rejection, mockery, and ostracism that often accompany the introduction of creative ideas can lead to feelings of alienation and subsequent psychopathology.

This model does not explain, however, why many creative individuals—whether or not they confront existential themes or face repeated rejection—do not exhibit signs of mental illness. In fact, a substantial body of literature suggests that artists and writers indulge in creative acts to purge themselves of preexisting depressive feelings (e.g., Greene, 1980; Kavaler-Adler, 1991). Creative endeavor, therefore, appears to be a self-induced therapy for, and not a cause of, psychopathology.

Model 2: Mental Illness Can Enhance Creativity

Several researchers have suggested that symptoms of certain forms of psychopathology may facilitate creativity (Hershman & Lieb, 1998; Jamison, 1993; Sass, 2000–2001). For example, Jamison (1993) proposed that the characteristics of hypomania may benefit creative idea generation. Flight of ideas may facilitate the activation of broad associational networks that is so important to creativity, and increased goal-directed activity may heighten motivation to work on creative projects. Increased energy and lack of need for sleep can provide additional resources to pursue creative activities. Meanwhile, depression, a state that has been associated with a more accurate perception of reality (see Taylor & Brown, 1988), can edit the ideas developed during hypomanic states. Depression can also serve as the subject matter for creative works, such as Emily Dickinson’s famous poem “There’s a Certain Slant of Light” or Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique.”

Eysenck (1995) suggested that psychosis-proneness (schizotypy) may contribute to creative ideation by invoking cognitive overinclusion, a trait of schizophrenic thought. Overinclusion is a state in which the individual becomes aware of material that is typically suppressed before entering consciousness. This overinclusive state may allow associations to be made among elements that do not ordinarily appear in conscious awareness together, thus promoting unusual creative ideas. Moreover, Sass (2000–2001) has suggested that the break with reality associated with such schizotypal cognition may enhance creativity, under some circumstances, by allowing the affected individual to view situations from a totally new perspective.

Alcohol ingestion may enhance creative inspiration by reducing anxieties and inhibitions (Norlander, 1999). Such a state may allow unusual ideas to enter consciousness as normal inhibitions are relaxed. Gustafson and Norlander have provided empirical evidence for the benefit of alcohol consumption in a series of controlled studies that tested alcohol’s effects on performance at various stages of the creative process (Norlander & Gustafson, 1996, 1998).

As with Model 1, this mental-illness-enhances-creativity model is not entirely satisfactory. Although certain symptoms associated with psychopathology, such as the flight of ideas, overinclusion, and reduced inhibitions, may be helpful in facilitating original or unusual ideas, the bulk of people who suffer from bipolar disorder, schizospectrum disorders, and alcohol abuse do not become unusually creative (see Richards et al., 1988).

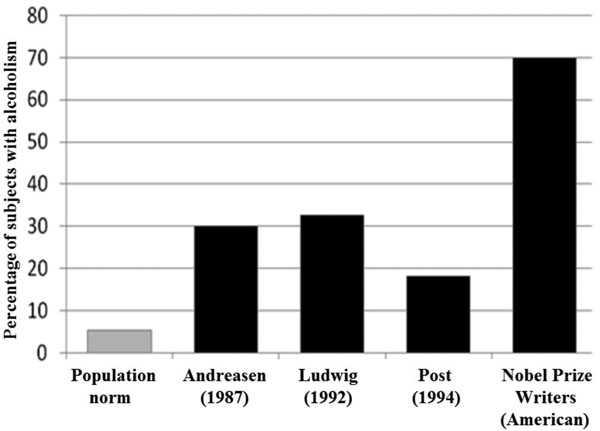

Model 3: The Shared Vulnerability Model of Creativity and Psychopathology

A third model suggests that psychopathology and creativity may share genetic components that are expressed as either pathology or creativity depending on the presence of other moderating factors (Berenbaum & Fujita, 1994; Carson, 2011). This model could explain why highly creative individuals are at greater risk for psychopathology than the general population. It could also explain why not all highly creative individuals express psychopathology and, conversely, why not all psychosis-prone individuals express unusual creativity, as well as the findings of increased creativity in the first-degree relatives of individuals with serious psychopathology. This model could, additionally, account for the stable maintenance of a one-percent schizophrenic population within the species, when it has been demonstrated that schizophrenics reproduce fewer offspring than normal (Schlager, 1995). The place of creativity in maintaining the adaptability of the species may provide a reproductive advantage for the transmission of at least some portion of the schizophrenic genotype (Crow, 1997).

To support the model, it would be necessary to identify one or more cognitive functions or traits that act as vulnerability factors and are common to both creativity and the forms of psychopathology to which creative individuals are vulnerable. It would also be necessary to identify protective cognitive factors that are not common to both creativity and psychosis and that could, by their presence or absence, interact with the vulnerability factors to produce high levels of either creativity or psychopathology.

Evidence for the Shared Vulnerability Model of Creativity and Psychopathology

Current evidence indicates that the disorders associated with creativity, as well as creativity itself, are both heritable and polygenetic (Berrettini, 2000; Whitfield, Nightingale, O’Brien, Heath, Birley, & Martin, 1998). The polygenetic nature of creativity-related disorders suggests that a constellation of gene-related contributions are necessary for the full symptom spectrum of these disorders to be present. However, a subset of these genetic contributions may affect cognitive or emotional experience in more benign—or even highly beneficial—ways, especially if combined with a set of protective mechanisms.

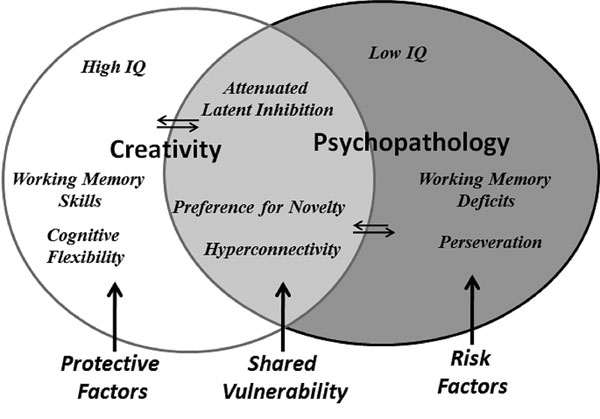

Based on anecdotal reports (see Ghiselin, 1952), as well as results from neuroimaging and genetic studies, it seems reasonable to propose a model in which factors common to both creativity and psychopathology act to increase access and attention to material normally processed below the level of conscious awareness, while protective cognitive factors allow for executive monitoring and control of such enhanced access. Protective factors would thus allow creatively productive individuals to exert metacognitive control over bizarre or unusual thoughts, enabling them to take advantage of such thoughts without being overwhelmed by them (Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2003; Simonton, 2005). Candidates for shared vulnerability factors include reduced latent inhibition, increased novelty seeking, and neural hyperconnectivity. Candidates for protective factors include high IQ, enhanced working memory capacity, and cognitive flexibility (see figure 9.4). These are, however, part of a preliminary model that will change and expand as our knowledge of the workings of the human brain progresses.

Figure 9.4

Shared vulnerability model of the creativity and psychopathology relationship. From Carson (2011). Used with permission.

Reduced Latent Inhibition as a Shared Neurocognitive Vulnerability Factor

Latent inhibition (LI) is the capacity to screen from conscious awareness stimuli previously experienced as irrelevant. As such, LI acts as a kind of cognitive filter. When LI is reduced, information that would typically be categorized as irrelevant is allowed into conscious awareness (Lubow & Gewirtz, 1995). Reduced LI is noted in individuals with schizophrenia and high levels of psychosis-proneness (Baruch, Hemsley, & Gray, 1988a,b; Lubow, Ingberg-Sachs, Zalstein-Orda, & Gewirtz, 1992). Reduced LI is also noted in nondisordered subjects who score high on the personality variable openness to experience, the trait often associated with creativity (Peterson & Carson, 2000), and in high-versus-low creative achievers of above average IQ (Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2003; Kéri, 2011). Reduced LI may enhance creativity by increasing the inventory of unfiltered stimuli available in conscious awareness, thereby improving the odds of synthesizing novel and useful combinations of stimuli (Carson et al., 2003).

Neuregulin 1 (NRG-1) has often been identified as one of the candidate genes for susceptibility to schizophrenia (Tosato, Dazzan, & Collier, 2005). Mice with a mutation of the NRG-1 gene have been shown to demonstrate reduced LI (Rimer, Barrett, Maldonado, Vock, & Gonzalez-Lima, 2005). Recently, Kéri (2009) reported that a polymorphism of the promoter region (the T/T genotype of SNP8NRG243177/rs6994992) of the NRG-1 gene that had previously been associated with psychosis was found to be prevalent in highly creative achievers with high IQs. Kéri (2009) suggested that the effect on prefrontal lobe functioning resulting from this genotype may be reduced LI, a mechanism we have already linked to both psychosis and creativity. The findings related to the NRG-1 polymorphisms support reduced LI phenomenon as a viable candidate for shared vulnerability between creativity and mental illness.

Novelty-Seeking as a Shared Neurocognitive Vulnerability Factor

Novelty-seeking is a personality trait associated with the motivation to explore novel aspects of ideas or objects. Creative individuals tend to score high in novelty-seeking and to prefer novel or complex stimuli over familiar or simple stimuli (McCrae, 1993; Reuter et al., 1995). Novelty-seeking provides internal rewards (via the dopaminergic reward system), and may arm creative individuals with intellectual curiosity and the intrinsic motivation to attend to creative work and novel ideas (Schweizer, 2006). However, novelty-seeking is also associated with alcohol abuse and addiction (Grucza et al., 2006), and with bipolar states of hypomania and mania. Novelty-seeking may be especially high in individuals with comorbid alcoholism and bipolar symptoms (Frye & Salloum, 2006). Therefore, novelty-seeking may be both an incentive for creative work and, simultaneously, a risk factor for psychopathology.

The A1+ allele of the TAQ 1A polymorphism of the DRD2 (D2 dopamine receptor) gene has been associated with novelty-seeking, schizophrenia, and addiction (Golimbet, Aksenova, Nosikov, Orlova, & Kaleda, 2003; Noble, 2000; Reuter, Schmitz, Corr, & Hennig, 2006). This same allele of the DRD2 gene was linked to creativity in a sample of German university students (Reuter, Roth, Holve, & Henning, 2006). Other genes related to dopamine functioning, including DRD4 (dopamine D4 receptor gene) and SLC6A3 (dopamine transporter gene), have also been linked to risk for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Serretti & Mandelli, 2008) and to novelty-seeking (Ekelund, Lichtermann, Jarvelin, & Peltonen, 1999). Variations in novelty-seeking, as determined by the availability of dopamine in sensitive regions of the brain, may constitute another shared vulnerability factor between creative cognition and the types of psychopathology associated with creativity.

Neural Hyperconnectivity as a Shared Neurocognitive Vulnerability Factor

A third potential shared vulnerability factor, neural hyperconnectivity, is characterized by an abnormal neural linking of brain areas that are not typically functionally connected. Hyperconnectivity, perhaps caused by faulty synaptic pruning during development, has been noted in both schizophrenics and their first-degree relatives, and may be linked to the bizarre associations often reported by schizophrenics (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009). Hyperconnectivity has also been noted in neuroimaging studies of synesthesia, the tendency to make cross-modal sensory associations (Hubbard & Ramachandran, 2005). Synesthesia has a genetic component, and is seven to eight times more prevalent among highly creative individuals than in the general population (Ramachandran & Hubbard, 2001). Brang and Ramachandran (2007) have suggested that the HTR2A (serotonin transporter) gene may underlie the expression of synesthesia and may therefore be implicated in anomalous neural connectivity. This gene has also been linked to schizotypy and risk for schizophrenia, although the alleles that confer this risk have been disputed (Abdolmaleky, Faraone, Glatt, & Tsuang, 2004).

Hyperconnectivity may also be evidenced by simultaneous activation of cortical areas. Brain-imaging studies have reported more alpha synchronization, both within and across hemispheres, in the brains of highly creative versus less creative subjects during creativity tasks, suggesting unusual patterns of connectivity (Fink & Benedek, current volume; Fink et al., 2009). Ramachandran and Hubbard (2001) speculate that hyperconnectivity may form the basis of metaphorical thinking, which has been associated with creative cognition, hypomania, psychotic episodes, and drug intoxication. Unusual patterns of neural connectivity may provide one neurological mechanism for associations between disparate stimuli that are the basis of creative thought, as well as a vulnerability to mania or psychosis.

High IQ as a Protective Factor

High IQ acts as a protective factor in individuals who are vulnerable to a variety of mental disorders (Barnett, Salmond, Jones, & Sahakian, 2006). Low IQ, on the other hand, has consistently been associated with risk for schizophrenia (Woodberry, Giuliano, & Seidman, 2008). The relationship between IQ and creativity is complex; however, a body of research indicates a threshold score for IQ of around 120 is necessary but not sufficient to promote high levels of creativity (Sternberg & O’Hara, 1999). Could high IQ act as a protective factor that promotes creativity in individuals that display at least some signs of vulnerability to schizophrenia?

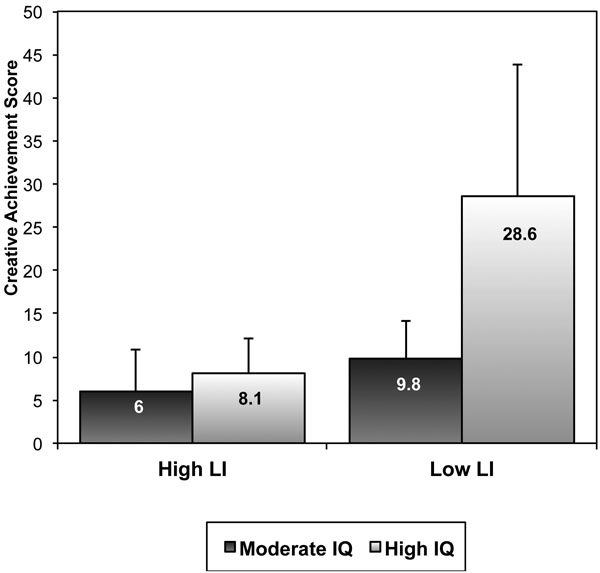

My colleagues and I hypothesized that if reduced LI increases the amount of stimuli available in conscious awareness, then high IQ may allow for the processing and manipulation of the additional stimuli in ways that lead to creative associations; conversely, low IQ combined with reduced LI may lead to confusion or becoming overwhelmed by the increased stimuli. In a series of studies, members of our lab found that the combination of reduced LI and high IQ predicted up to 30 percent of the variance in creative achievement scores (Carson et al., 2003) (see figure 9.5). These results suggest that when combined with reduced LI (a shared vulnerability factor), high IQ acts as a protective factor while low IQ is an additional risk factor for psychosis.

Figure 9.5

High IQ and reduced latent inhibition predict creative achievement in eminent achievers and controls. Taken from Carson et al. (2003).

Enhanced Working Memory as a Protective Factor

Just as high IQ may allow for the advantageous processing of additional stimuli in conscious awareness due to reduced LI, enhanced working memory capacity (generally considered to be one facet of IQ) might also confer this advantage. Support for this hypothesis emerged in a study of high-achieving student writers, composers, and artists at Harvard. LI deficits combined with high scores on a measure of working memory for abstract forms predicted over 25 percent of the variance in creative achievement scores (Carson, 2001). Working memory for abstract forms has also been shown to predict the ability to solve insight problems (a type of creativity task) in a sample of college undergraduates (DeYoung, Flanders, & Peterson, 2008). One of the most viable theories of creativity suggests that creative ideas arise from combining and rearranging bits of information that are only remotely associated with each other (Mednick, 1962). Clearly, then, the ability to hold and process a large number of bits of information simultaneously without becoming confused or overwhelmed should predispose the individual to creative rather than disordered cognition.

Cognitive Flexibility as a Protective Factor

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to disengage attention from one stimulus or concept and refocus it on another through conscious mental control. The opposite of cognitive flexibility, perseveration, is a hallmark of schizophrenia (Waford & Lewine, 2010). Cognitive flexibility may offer creative persons the ability to change perspectives and disengage from unusual thoughts or perceptions, rather than interpreting them in a psychotic manner (O’Connor, 2009).

Dietrich (2003) has suggested that creative individuals have the ability to modulate neurotransmitter systems in the brain to allow for temporary cognitive disinhibition. Evidence from several sources indicates that cognitive flexibility is dependent on dopamine availability in the prefrontal cortex (Darvas & Palmiter, 2011). Prefrontal dopamine pathways have been shown to exercise control over dopamine availability in striatal areas (Davis, Kahn, Ko, & Davidson, 1991) that, in turn, are implicated in both reduced LI and psychosis-proneness (Lubow & Gewirtz, 1995; Woodward et al., 2011). It is possible that creative individuals are able to use cognitive flexibility to promote alternating states of reduced LI and conscious executive control of attention. This may allow unusual and creative ideas to slip into consciousness awareness, while also allowing for the deliberate and rational evaluation of these ideas.

Conclusions

Despite the desirability and adaptability of human creativity, research indicates that creative individuals are at greater risk for certain forms of psychopathology than are members of the general public. Several models have been presented to account for the creativity-psychopathology relationship; however, a model of shared neurocognitive vulnerability best accounts for the available research findings.

Creative individuals may share neurocognitive vulnerabilities that are also characteristic of certain forms of mental pathology. These mechanisms may grant access to disinhibited states of consciousness, increase attention to novelty, and promote unusual associations through anomalous neural connectivity. Cognitive strengths, such as high IQ, good working memory capacity, and cognitive flexibility, may interact with these vulnerabilities to enhance creativity and to act as protective factors against severe forms of the relevant psychopathologies.

The shared vulnerability model currently includes only factors for which there is some corroborating support from brain imaging and molecular biology studies. However, there are likely additional shared vulnerabilities and protective factors that warrant inclusion. Further, the factors considered in this current model focus only on neurocognitive mechanisms. Yet recent research has emphasized the interaction of neurocognitive risk factors and environmental factors. For instance, Kéri (2011) recently demonstrated that social networks (a well-known protective factor for many mental disorders) can interact with neurocognitive mechanisms (such as reduced LI) to predict creative achievement. Future research will extend the shared vulnerability model to include the interactions of neurocognitive and environmental factors.

Clearly the inner demons of psychopathology and the voice of the muse share common characteristics within the brain and may occasionally call to the same individuals. As we learn more about the shared vulnerabilities of creativity and psychopathology, we may be able to use this knowledge to treat certain mental illnesses and effect outcomes that not only reduce human suffering but also promote human adaptability through creativity enhancement.

References

Abdolmaleky, H. M., Faraone, S. V., Glatt, S. J., & Tsuang, M. T. (2004). Meta-analysis of association between the T102C polymorphism of the 5HT2a receptor gene and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 67, 53–62.

Abraham, A., Windmann, S., Siefen, R., Daum, I., & Gunturkun, O. (2006). Creative thinking in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Neuropsychology, 12, 111–123.

Andreasen, N. (1987). Creativity and mental illness: Prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1288–1292.

Andreasen, N. (2008). Creativity and mood disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10, 252–255.

Andreasen, N. J., & Powers, P. S. (1975). Creativity and psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 70–73.

Aristophanes. (424 b.c.). The knights. Retrieved from http://classics.mit.edu/Aristophanes/knights.pl.txt.

Aristotle. (1984). Problems. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The complete works of Aristotle (Vol. 2, pp. 1319–1527). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ashby, F. G., Isen, A. M., & Turken, A. U. (1999). A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Psychological Review, 106, 529–550.

Barnett, G. H., Salmond, G. H., Jones, P. B., & Sahakian, B. J. (2006). Cognitive reserve in neuropsychiatry. Psychological Medicine, 36, 1053–1064.

Barron, F. (1955). The disposition toward originality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51, 478–485.

Barron, F. (1969). Creative person and creative process. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Baruch, I., Hemsley, D. R., & Gray, J. A. (1988a). Differential performance of acute and chronic schizophrenics in a latent inhibition task. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 176, 598–606.

Baruch, I., Hemsley, D. R., & Gray, J. A. (1988b). Latent inhibition and “psychotic proneness” in normal subjects. Personality and Individual Differences, 9, 777–783.

Becker, G. (2001). The association of creativity and psychopathology: Its cultural-historical origins. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 45–53.

Bentley, G. E., Jr. (2001). The stranger from paradise: A biography of William Blake. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Berenbaum, H., & Fujita, F. (1994). Schizophrenia and personality: Exploring the boundaries and connections between vulnerability and outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 148–158.

Berrettini, W. H. (2000). Susceptibility loci for bipolar disorder: Overlap with inherited vulnerability to schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 47, 245–251.

Brang, D., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2007). Psychopharmacology of synesthesia: The role of serotonin S2a receptor activation. Medical Hypotheses, 70, 903–904.

Brod, J. H. (1987). Creativity and schizotypy. In G. Claridge (Ed.), Schizotypy: Implications for illness and health (pp. 274–298). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burch, G. St. J., Pavelis, C., Hemsley, D. R., & Corr, P. J. (2006). Schizotypy and creativity in visual artists. British Journal of Psychology, 97, 177–190.

Buss, D., & Barnes, M. (1986). Preferences in human mate selection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 559–570.

Carson, S. H. (2011). Creativity and psychopathology: A genetic shared-vulnerability model. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 144–153.

Carson, S.H. (2001). Demons and muses: An exploration of cognitive features and vulnerability to psychosis in creative individuals. Retrieved from Dissertations and Theses database. Harvard University. (AAT3011334).

Carson, S. H., Peterson, J. B., & Higgins, D. M. (2003). Decreased latent inhibition is associated with increased creative achievement in high-functioning individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 499–506.

Cattell, R. B., & Drevdahl, J. E. (1955). A comparison of the personality profile (16PF) of eminent researchers with that of eminent teachers and administrators, and of the general populations. British Journal of Psychology, 46, 248–261.

Claridge, G. (Ed.). (1997). Schizotypy: Implications for illness and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Condivi, A. (ca. 1520/1999). The life of Michelangelo. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Cox, A. J., & Leon, J. L. (1999). Negative schizotypal traits in the relation of creativity to psychopathology. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 25–36.

Cramond, B. (1994). The relationship between ADHD and creativity. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, April 2–8, 1994: New Orleans.

Crow, T. J. (1997). Is schizophrenia the price that Homo sapiens pays for language? Schizophrenia Research, 28, 127–141.

Dardis, T. (1989). The thirsty muse: Alcohol and the American writer. New York: Tichnor & Fields.

Darvas, M., & Palmiter, R. D. (2011). Contributions of striatal dopamine signaling to the modulation of cognitive flexibility. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 704–707.

Davis, K. L., Kahn, R. S., Ko, G., & Davidson, M. (1991). Dopamine in schizophrenia: A review and reconceptualization. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1474–1486.

de Manzano, O., Cervenka, S., Karabanov, A., Farde, L., & Ullén, F. (2010). Thinking outside a less intact box: Thalamic dopamine d2 receptor densities are negatively related to psychometric creativity in healthy individuals. PLoS ONE, 5, e10670.

DeYoung, C. G., Flanders, J. L., & Peterson, J. B. (2008). Cognitive abilities involved in insight problem solving: An individual differences model. Creativity Research Journal, 20, 278–290.

Dietrich, A. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: The transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and Cognition, 12, 231–256.

Dykes, M., & McGhie, A. (1976). A comparative study of attentional strategies of schizophrenic and highly creative normal subjects. British Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 50–56.

Drevdahl, J. E., & Cattell, R. B. (1958). Personality and creativity in artists and writers. Journal of Clinical Personality, 14, 107–111.

Ekelund, J., Lichtermann, D., Jarvelin, M. R., & Peltonen, L. (1999). Association between novelty seeking and the type 4 dopamine receptor gene in a large Finnish cohort sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1453–1455.

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Creativity as a product of intelligence and personality. In D. H. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence (pp. 231–248). New York: Plenum Press.

Feist, G. F. (1999). The influence of personality on artistic and scientific creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 273–296). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Benedek, M., Reishofer, G., Hauswirth, V., Fally, M., et al. (2009). The creative brain: Investigation of brain activity during creative problem solving by means of EEG and fMRI. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 734–748.

Frey, J. (1994). Toulouse-Lautrec: A life. New York: Penguin.

Frye, M. A., & Salloum, I. M. (2006). Bipolar disorder and comorbid alcoholism: Prevalence rate and treatment considerations. Bipolar Disorders, 8, 677–685.

Galvin, R. (2004). William Blake: Visions and verses. Humanities, 25, 16–20.

Gangemi, J. (2006). Creativity comes to B-School. Business Week, March 26, 2006. http://www.businessweek.com/print/bschools/content/mar2006/bs20060326 _8436_bs001.htm?chan_bs.

Ghiselin, B. (1952). The creative process. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Golimbet, V. E., Aksenova, M. G., Nosikov, V. V., Orlova, V. A., & Kaleda, V. G. (2003). Analysis of the linkage of the Taq1A and Taq1B loci of the dopamine D2 receptor gene with schizophrenia in patients and their siblings. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, 33, 223–225.

Goodwin, D. W. (1992). Alcohol as muse. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 46, 422–433.

Green, M. J., & Williams, L. M. (1999). Schizotypy and creativity as effects of reduced cognitive inhibition. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 263–276.

Greene, G. (1980). Ways of escape. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Grucza, R. A., Cloninger, C. R., Bucholz, K. K., Constantino, J. N., Schuckit, M. I., Dick, D. M., et al. (2006). Novelty seeking as a moderator of familial risk for alcohol dependence. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 1176–1183.

Hemingway, E. (1954). Banquet speech. Nobel Banquet on December 10, 1954. Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved from http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1954/ hemingway-speech.html.

Hershman, D. J., & Lieb, J. (1998). Manic depression and creativity. New York: Prometheus.

Heston, L. L. (1966). Psychiatric disorders in foster home reared children of schizophrenic mothers. British Journal of Psychiatry, 112, 819–825.

Hubbard, E. M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2005). Neurocognitive mechanisms of synaesthesia. Neuron, 48, 509–520.

Jamison, K. (1989). Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry, 52, 125–134.

Jamison, K. R. (1993). Touched with fire. New York: Free Press.

Jensen, E. F. (2001). Schumann. New York: Oxford University Press.

Karlsson, J. L. (1970). Genetic association of giftedness and creativity with schizophrenia. Hereditas, 66, 177–182.

Kavaler-Adler, S. (1991). Emily Dickinson and the subject of seclusion. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 51, 21–38.

Keefe, J. A., & Magaro, P. A. (1980). Creativity and schizophrenia: An equivalence of cognitive processing. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 89, 390–398.

Kéri, S. (2009). Genes for psychosis and creativity: A promoter polymorphism of the neuregulin 1 gene is related to creativity in people with high intellectual achievement. Psychological Science, 20, 1070–1073.

Kéri, S. (2011). Solitary minds and social capital: Latent inhibition, general intellectual functions and social network size predict creative achievements. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5, 215–221.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

Kinney, D. K., Richards, R., Lowing, P. A., LeBlanc, D., Zimbalist, M. E., & Harlan, P. (2000–2001). Creativity in offspring of schizophrenic and control parents: An adoption study. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 17–25.

Lombroso, C. [1891] (1976). The man of genius. London: Walter Scott.

Lubow, R. E., & Gewirtz, J. C. (1995). Latent inhibition in humans: Data, theory, and implications for schizophrenia. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 87–103.

Lubow, R. E., Ingberg-Sachs, Y., Zalstein-Orda, N., & Gewirtz, J. C. (1992). Latent inhibition in low and high “psychotic-prone” normal subjects. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 563–572.

Ludwig, A. (1990). Alcohol input and creative output. British Journal of Addiction, 85, 953–963.

Ludwig, A. (1992). Creative achievement and psychopathology: Comparison among professions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 46, 330–354.

Ludwig, A. (1994). Mental illness and creative activity in female writers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1650–1656.

Ludwig, A. (1995). The price of greatness: Resolving the creativity and madness controversy. New York: Guilford Press.

MacKinnon, D. W. (1962). The nature and nurture of creative talent. American Psychologist, 17, 484–495.

Maher, B. (1972). The language of schizophrenia: A review and interpretation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 120, 3–17.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd Ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Mason, O., & Claridge, G. (2006). The Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE): Further description and extended norms. Schizophrenia Research, 82, 203–211.

Matthew, C. A. (2009). Leader creativity as a predictor of leading change in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 1–41.

McCrae, R. R. (1993). Openness to experience as a basic dimension of personality. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 13, 39–55.

Meaker, M. J. (1964). Sudden endings: 13 profiles in depth of famous suicides. Garden, NY: Doubleday.

Mednick, S. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69, 220–232.

Miller, G. F. (2001). Aesthetic fitness: How sexual selection shaped artistic virtuosity as a fitness indicator and aesthetic preference as mate choice criteria. Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts, 2, 20–25.

Nasar, S. (1998). A beautiful mind: The life of mathematical genius and Nobel laureate John Nash. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Nelson, B., & Rawlings, D. (2010). Relating schizotypy and personality to the phenomenology of creativity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 388–399.

Nettle, D. (2006). Schizotypy and mental health amongst poets, visual artists, and mathematicians. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 876–890.

Nettle, D., & Clegg, H. (2006). Schizotypy, creativity, and mating success in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Biological Sciences, 273, 611–615.

Noble, E. P. (2000). Addiction and its reward process through polymorphisms of the D2 dopamine receptor gene: A review. European Psychiatry, 15, 79–89.

Norlander, T. (1999). Inebriation and inspiration? A review of the research on alcohol and creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 33, 22–44.

Norlander, T., & Gustafson, R. (1998). Effects of alcohol on a divergent figural fluency test during the illumination phase of the creative process. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 265–274.

Norlander, T., & Gustafson, R. (1996). Effects of alcohol on scientific thought during the incubation phase of the creative process. Journal of Creative Behavior, 30, 231–248.

O’Connor, K. (2009). Cognitive and meta-cognitive dimensions of psychoses. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 152–159.

O’Reilly, T., Dunbar, R., & Bentall, R. (2001). Schizotypy and creativity: An evolutionary connection. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 1067–1078.

Ostwald, P. (1985). Schumann: The inner voices of a musical genius. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Peterson, J. B., & Carson, S. (2000). Latent inhibition and openness to experience in a high-achieving student population. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 323–332.

Pickover, C. A. (1998). Strange brains and genius. New York: Plenum Press.

Plato. (360 b.c.) Phaedrus. MIT Internet Classics. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/phaedrus.html.

Poreh, A. M., Whitman, D. R., & Ross, T. P. (1994). Creative thinking abilities and hemispheric asymmetry in schizotypal college students. Current Psychology, 12, 344–352.

Post, F. (1994). Creativity and psychopathology: A study of 291 world-famous men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 22–34.

Prentky, R. (1979). Creativity and psychopathology: A neurocognitive perspective. In B. Maher (Ed.), Progress in experimental personality research (Vol. 9, pp. 1–39). New York: Academic Press.

Prentky, R. (1989). Creativity and psychopathology: Gamboling at the seat of madness. In J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning, & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 243–270). New York: Plenum Press.

Prentky, R. (2000–2001). Mental illness and roots of genius. Creativity Research Journal, 13(1), 95–104.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Hubbard, E. M. (2001). Synaesthesia—a window into perception, thought, and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8, 3–34.

Rawlings, D., & Locarnini, A. (2008). Dimensional schizotypy, autism, and unusual word associations in artists and scientists. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 465–471.

Reuter, M., Panksepp, J., Schnabel, N., Kellerhoff, N., Kempel, P., & Hennig, J. (1995). Personality and biological markers of creativity. European Journal of Personality, 19, 83–95.

Reuter, M., Roth, S., Holve, K., & Henning, J. (2006a). Identification of first genes for creativity: A pilot study. Brain Research, 1069, 190–197.

Reuter, M., Schmitz, A., Corr, P., & Hennig, J. (2006b). Molecular genetics support Gray’s personality theory: The interaction of COMT and DRD2 polymorphisms predicts the behavioural approach system. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 9, 155–166.

Richards, R. (1999). Everyday creativity. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (Vol. 1, pp. 683–687). San Diego: Academic Press.

Richards, R. (1990). Everyday creativity, eminent creativity, and health: “Afterview” for CRJ issues on creativity and health. Creativity Research Journal, 3, 300–326.

Richards, R., Kinney, D. K., Lunde, I., Benet, M., & Merzel, A. P. C. (1988). Creativity in manic—depressives, cyclothymes, their normal relatives, and control subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 281–288.

Rimer, M., Barrett, D. W., Maldonado, M. A., Vock, V. M., & Gonzalez-Lima, F. (2005). Neuregulin-1 immunoglobulin-like domain mutant mice: Clozapine sensitivity and impaired latent inhibition. Neuroreport, 16, 271–275.

Rogers, C. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. London: Constable.

Sass, L. A. (2000–2001). Schizophrenia, modernism, and the “creative imagination”: On creativity and psychopathology. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 55–74.

Schildkraut, J., Hirshfeld, A., & Murphy, J. (1994). Mind and mood in modern art, II: Depressive disorders, spirituality, and early deaths in the abstract expressionist artists of the New York school. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 482–488.

Schlager, D. (1995). Evolutionary perspectives on paranoid disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 18, 263–279.

Schuldberg, D., French, C., Stone, B. L., & Heberle, J. (1988). Creativity and schizotypal traits: Creativity test scores and perceptual aberration, magical ideation, and impulsive nonconformity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 176, 648–657.

Schweizer, T. J. (2006). The psychology of novelty-seeking, creativity, and innovation: Neurocognitive aspects within a work—psychological perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 15, 164–172.

Serretti, A., & Mandelli, L. (2008). The genetics of bipolar disorder: Genome “hot regions,” genes, new potential candidates, and future directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 13, 742–771.

Simonton, D. K. (2005). Are genius and madness related? Contemporary answers to an ancient question. Psychiatric Times, 22, 21–22.

Sternberg, R. J., & O’Hara, L. A. (1999). Creativity and intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 251–272). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Styron, W. (1990). Darkness visible: A memoir of madness. New York: Random House.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being—a social psychological perspective on mental-health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.

Tosato, S., Dazzan, P., & Collier, D. (2005). Association between the neuregulin 1 gene and schizophrenia: A systematic review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 31, 613–617.

Waford, R. N., & Lewine, R. (2010). Is perseveration uniquely characteristic of schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Research, 118, 128–133.

White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2006). Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1121–1131.

Whitfield, J. B., Nightingale, B. N., O’Brien, M. E., Heath, A. C., Birley, A. J., & Martin, N. G. (1998). Molecular biology of alcohol dependence: A complex polygenic disorder. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 36, 633–636.

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Thermenos, H. W., Milanovic, S., Tsuang, M. T., Faraone, S. V., McCarley, R. W., et al. (2009). Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 1279–1284.

Woodberry, K. A., Giuliano, A. J., & Seidman, L. J. (2008). Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 579–587.

Woodward, N. D., Cowan, R. L., Park, S., Ansari, M. S., Baldwin, R. M., Li, R., et al. (2011). Correlation of individual differences in schizotypal personality traits with amphetamine-induced dopamine release in striatal and extrastriatal brain regions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 418–426.

World Health Organization. (2001). The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization.