12

Fostering Creativity: Insights from Neuroscience

There is now general consensus that creativity is a componential trait. As such, it stands to reason that fostering any of its underlying components should in turn benefit creative production. With some variation, the three fundamental components of creativity are considered to be motivation (task commitment), ability (domain expertise), and creative thinking skills (Amabile, 1998; Renzulli, 1986). Accordingly, a large body of behavioral evidence has demonstrated that creativity is enhanced when motivation is intrinsically oriented (Amabile, 1985), levels of ability and expertise are high (Weisberg, 1999), and creative thinking skills (e.g., divergent thinking) are superior (Plucker & Renzulli, 1999).

However, can evidence gleaned from the structure and function of the brain enhance our ability to foster creativity? I argue that it can, for two reasons. First, interventions designed to enhance motivation, abilities, and skills must be realized in the brain and therefore have traceable neural correlates, which in turn can be used to verify that learning has occurred. In fact, much evidence now points to training-based neural plasticity in the brain—both structurally and functionally. For example, Schlaug et al. (2009) have demonstrated structural changes in the anterior midbody of the corpus callosum (which connects the premotor and supplementary motor areas of the two hemispheres) following musical training. Similarly, functional changes in the brain’s frontoparietal system have been shown to occur following training of working memory (WM) (see Klingberg, 2010)—a critical ability for most types of creativity. These findings suggest that researchers can use data derived from brain structure and function to confirm and in turn optimize training regimens for creativity.

A related but conceptually separable contribution the neurosciences can make to foster creativity is the information they provide on the brain’s metabolic rate. Specifically, the uptake of glucose in positron emission tomography (PET) and the blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signal in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) provide direct and indirect information about the metabolic requirements of various cognitive tasks. Interventions (e.g., cognitive training) that increase the brain’s neural efficiency (by reducing its metabolic demands) for creative tasks provide another avenue for facilitating creativity. For example, it is now known that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the levels and stability of glucose in the brain vary such that it is not always present in ample amounts to optimally support learning and memory (see McNay, McCarty, & Gold, 2001). Thus, given the resource limitations that exist in the brain, interventions that lower the limiting metabolic thresholds for any component of creative cognition should theoretically facilitate its occurrence.

In this chapter, I review two strands of neuroscientific research that I believe have shown promise in fostering creativity. The first involves enhancement of WM and fluid intelligence through cognitive training. Given that WM ability and fluid intelligence are related positively to many forms of creativity (Nusbaum & Silvia, 2011; Sligh, Conners, & Roskos-Ewoldsen, 2005), the ability to use neuroscientific data to track enhancement of WM and fluid intelligence in the brain can be used to optimize creativity training. In this sense, neuroscientific data can play a confirmatory role in establishing training effects. The second strand of relevant research is focused on the concept of neural efficiency and on the utility of cognitive interventions to increase neural efficiency for creativity tasks. Although this literature is relatively limited compared to the literature on the enhancement of WM and fluid intelligence, emerging evidence suggests that it is possible to make the neural processing more efficient through behavioral intervention (see Vartanian et al., 2013).

Improving Working Memory

Working memory involves the ability to maintain and manipulate information. WM is hypothesized to play an important role in most types of creativity. For example, one of the most common engines for the generation of creative ideas is the novel and useful combination of concepts previously thought to be unrelated (Poincaré, 1913; Vartanian, Martindale, & Matthews, 2009; see also Sternberg, 1999). It is immediately evident that this combinatorial engine requires the maintenance and manipulation of two or more concepts—for which WM is a necessity. Thus, the question arises: can we improve WM capacity through training? The answer, based on evidence from a large number of studies that have investigated the impact of cognitive or brain training on cognitive capacity—specifically WM—appears to be yes (for reviews see Klingberg, 2010; Morrison & Chein, 2011). The central question in this research area is not whether performance on any given cognitive task can be improved by training—it has long been known that it can—but whether improvements in a cognitive task as a function of WM training can transfer to other untrained tasks or to improvements in general cognitive function. The issue of transfer is critical for fostering creativity because ideally it would be possible to train on a small set of “core” tasks and observe improvements in a variety of target creativity tasks.

On balance, the evidence suggests that there is reason to be optimistic about transfer effects as a function of WM training, although a number of qualifiers apply. First, for the most part studies that have shown transfer effects have been conducted within laboratory settings in which a strict regimen of training has been administered by trained personnel. Transfer effects have not been shown for individuals outside of the lab engaged in unsupervised daily cognitive training (Owen et al., 2010). Second, training effects are more likely to transfer if subjects train on “core” WM tasks, likely because such training targets domain-general abilities that underlie many different target activities. In contrast, although “strategy training” can result in improvements in the specific task used for training, it tends not to exhibit far-reaching transfer effects. Finally, although training and transfer effects have been demonstrated in young adults, the evidence is less convincing for seniors. For example, some data with older adults suggest that the improvements related to cognitive training extend only to the trained task and sometimes to closely related memory measures (Li et al., 2008). However, when researchers have used ecologically valid measures of verbal learning and “everyday attention,” as well as self-reported functional measures, transfer of improvements has been observed (Richmond et al., 2011). This suggests that cognitive training could be efficacious in older adults if transfer effects were studied using ecologically valid target tasks that more closely resemble the real-life activities of older adults. However, there is also evidence to suggest that in this cohort (compared to young adults) glucose may be depleted much more quickly from key brain regions during cognitive performance (McNay et al., 2001), such that effective training may have to be coupled with external metabolic interventions.

The conclusion from this large body of literature is that given the right conditions, WM training does transfer to improvements in target tasks as well as general cognitive function. To the extent that creativity relies on WM, this finding is very promising for interventions aimed at improving the “ability” component of creative production (Renzulli, 1986).

What is the impact, if any, of WM training on neural function? The answer to this question is rather nuanced. Recently, Klingberg (2010) reviewed ten fMRI studies that had investigated the impact of repeated performance of WM tasks on neural function. These studies could be divided into two categories. The first category involved studies (N = 6) in which researchers investigated the impact of repeated training on the trained tasks themselves. Five of these studies were structurally similar in that the impact of repeated WM training was examined based on relatively short training periods ranging from thirty minutes to two hours. The training tasks included delayed matching-to-sample and object, verbal, and spatial WM tasks. The pattern of results across studies was surprisingly consistent, uniformly demonstrating reductions in the BOLD response in various structures including the precentral sulcus, occipital lobe, parietal lobe, cingulate cortex, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), frontopolar cortex, and inferior frontal cortex. One of the six studies that used an entirely different design generated a different pattern of results. Specifically, Hempel et al. (2004) instructed their participants to train on the visuospatial n-back daily for four weeks. Briefly, on each trial of the n-back task the participant must decide whether the information currently present matches information presented a specified number of trials earlier—whether auditory or visual. By definition, optimal performance necessitates updating the contents of WM as a function of instructions. Hempel et al. (2004) tested the effect of training on neural function twice—two weeks and four weeks after training. Whereas activation in DLPFC and parietal lobe was elevated at two weeks, it was reduced at four weeks. Thus, aside from Hempel et al.’s (2004) study, the overall pattern of results suggests that when training periods are relatively short and the target is the trained task, reductions in the BOLD signal will be observed. This pattern closely resembles early PET studies in which repeated practice with effortful tasks reduced the extent of brain activation over time (for review see Jung & Haier, 2007).

The second category involved studies (N = 4) in which researchers investigated the impact of repeated training on transfer to other untrained tasks. Furthermore, these studies relied on longer and more frequent training regimens, ranging from ten hours over ten days to twenty hours over ten weeks. The tasks included updating, and verbal, object, and visuospatial WM tasks. Compared to training studies in which the effects were examined on the trained tasks, these studies generated a rather heterogeneous pattern of results including increases in the BOLD response in DLPFC, parietal lobe, caudate, and left inferior frontal cortex, accompanied by decreases in the BOLD response in DLPFC, parietal lobe, and the cingulate. It is important to note that despite differences in the direction of the effect across these four studies, the effects were localized in the WM frontoparietal network and the basal ganglia, a structure involved in selection of relevant information in WM tasks (McNab & Klingberg, 2008).

In conclusion, when combined together, the results of fMRI training studies based on trained and transferred skills are consistent with the interpretation that training targets the network of brain regions implicated in domain-general aspects of WM including DLPFC, parietal cortex, and basal ganglia (Wager & Smith, 2003). Furthermore, there is reason to believe that transfer from the trained task to the target task will be facilitated to the extent that the two tasks recruit overlapping cortical regions (see Morrison & Chein, 2011). Despite these encouraging results, a number of key issues remain unresolved. First, because activation in the frontoparietal network is also correlated with task difficulty (Barch et al., 1997), at the moment it is not possible to determine with certainty whether its responsiveness to training is a function of WM engagement or whether it is a by-product of responsiveness to task difficulty. For example, the reduced BOLD response in the frontoparietal network following short WM training regimens may simply be because the task becomes less difficult over time, and not necessarily because of improved WM capacity. Second, repeated training on WM tasks may involve changes to factors other than WM capacity, such as priming, automaticity, familiarity, and strategy learning. This means that although, based on improvements in performance as well as targeted variation in neural function, repeated WM training appears to “work” (Morrison & Chein, 2011), it is more difficult to isolate specifically which of the underlying factors associated with repeated training is responsible for the observed effects (see also Buschkuehl, Jaeggi, & Jonides, 2012).

Improving Fluid Intelligence

Fluid intelligence is defined as the ability to adapt to new situations and is characterized by increased abstraction and complexity in thinking (Cattell, 1963). In contrast, crystallized intelligence is defined as repository of knowledge and skills acquired through learning and experience. Not surprisingly, crystallized intelligence tends to increase across the lifespan as people acquire new knowledge and learn new skills (Deary, Penke, & Johnson, 2010). Furthermore, it has long been known that it is possible to boost crystallized intelligence through teaching. In contrast, fluid intelligence has historically not been viewed as an improvable ability. Coupled with the fact that it has a very high heritability quotient, fluid intelligence has historically been considered to be strongly influenced by genetics, although recent evidence suggests that plasticity is retained at least into the teenage years (Ramsden et al., 2011).

This traditional view was challenged by an important recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan who reported evidence demonstrating that it was in fact possible to boost fluid intelligence. Specifically, Jaeggi, Buschkuehl, Jonides, and Perrig (2008) administered a dual n-back task to participants in the experimental condition, who trained for various number of sessions ranging among 8, 12, 17, and 19 days. The dual n-back task used was very effortful as it required simultaneous tracking of visual and auditory information. In addition, its difficulty level was adjusted in relation to individual performance. To assess fluid intelligence, participants were assessed using either Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) test or the short version of the Bochumer Matrizen-Test (BOMAT) prior to and following the completion of training. The results demonstrated that WM capacity (as measured by mean n-back level) increased over the course of training, and that longer training resulted in greater gain. In addition, compared to a passive control condition, participants in the experimental condition demonstrated significant gain in fluid intelligence based on pre-post-change in test scores. Perhaps most interestingly, there was a dose-response effect such that a longer frequency of training was correlated with greater gain in fluid intelligence.

The same team subsequently tested the effectiveness of cognitive training in elementary and middle school children by means of a videogame-like WM task (Jaeggi, Buschkuehl, Jonides, & Shah, 2011). The results largely supported earlier findings, with the caveat that gains in fluid intelligence were observed only in those children who exhibited significant WM improvement in the course of training. This is perhaps not surprising, given that variation in the motivation to perform may play a bigger role in children than it does in adults and would therefore be an important consideration. Regardless, the set of studies by Jaeggi and colleagues demonstrates that it is possible to boost fluid intelligence, and that the gains based on WM capacity are transferrable to fluid intelligence. This feature opens up the possibility to boost performance in target tasks that rely on fluid intelligence through WM training, potentially opening up a number of applications in educational and professional domains (Sternberg, 2008).

Fluid Intelligence and Creativity

Given the aforementioned definition of fluid intelligence, it is rather surprising that this construct has not played a more prominent role in studies of creativity. Perhaps some of this may have to do with the fact that psychometric intelligence and creativity have shown a weak relationship across studies in the past. For example, regarding the correlation between intelligence and creativity, a recent meta-analysis of 447 effect sizes reported an average weighted effect size of only r = 0.174 (Kim, 2005). However, more recent evidence suggests that creativity loads heavily on fluid intelligence. For example, Nusbaum and Silvia (2011) used modern approaches to creativity assessment and latent variable modeling to investigate the role of fluid intelligence in divergent thinking. They reported two important findings. First, the effect of fluid intelligence on divergent thinking was mediated by executive switching (study 1). Executive switching was measured as a function of the number of times subjects switched idea categories during divergent thinking. Subsequently, the researchers investigated the extent to which participants were able to implement an effective strategy for an unusual uses task (study 2). The results demonstrated that only those participants high in fluid intelligence were able to do so, consistent with their higher ability to maintain access to the strategy and use it despite interference. The results of Nusbaum and Silvia (2011) demonstrate that fluid intelligence underlies the extent to which participants can implement the tools necessary for divergent thinking, including category shifts and strategy use (see also Sligh et al., 2005).

Very similar conclusions can be drawn from the work of Gilhooly, Fioratou, Anthony, and Wynn (2007), who used a think-aloud strategy to analyze the characteristics of the responses that were generated in an alternate uses task. They demonstrated that earlier uses generated in response to a prompt are frequently not creative, and involve well-known uses derived from long-term memory. Having exhausted mnemonic recall, uses generated later in the sequence are frequently more creative and involve strategies that load on executive function, such as disassembly and reassembly of parts (experiment 1). Subsequently, they showed that the generation of new creative uses was predicted by performance on letter fluency—an executive loading task (experiment 2). The results of Gilhooly et al. (2007) are congruent with those reported by Nusbaum and Silvia (2011), suggesting that despite the low correlations reported between creativity and intelligence in earlier studies (see Kim, 2005), creativity does load on fluid intelligence and executive function. Of course, given Jaeggi et al.’s (2008, 2011) demonstrations that fluid intelligence can be improved by a regimen of repeated training on the n-back task, this brings up the obvious question: can creativity be improved by improving WM capacity based on training on the n-back task? Before we answer this question, we will take a short detour and briefly review the current state of knowledge about the neuroscience of intelligence (for a more in-depth review see Jung & Haier, this vol.).

Neuroscience of Intelligence

The neuroscience of intelligence has been the focus of much interest recently (for reviews see Deary et al., 2010; Jung & Haier, 2007, this vol.). Based on a large-scale review of all available structural and functional neuroimaging studies, Jung and Haier (2007) proposed the parieto-frontal integration theory of intelligence (P-FIT). This theory localizes individual differences in intelligence to specific frontal and parietal regions (see Jung & Haier, 2007; figure 11.2, this vol.). There are two issues of relevance for the purposes of the current chapter that must be highlighted. First, the neural correlates of general fluid intelligence are embedded within P-FIT, in particular in the lateral prefrontal cortex (Duncan et al., 2000; Gray, Chabris, & Braver, 2003). Interestingly, these are the same brain regions that are heavily implicated in inhibition and (executive) control of attention (Aron, Robbins, & Poldrack, 2004). This is not surprising, given that an important component of intelligent behavior involves selective attention to relevant information.

Second, although by no means a universal observation, a large number of studies have reported an inverse relation between fluid intelligence and metabolic rate in a variety of cognitive tasks (Deary et al., 2010; Jung & Haier, 2007, this vol.; Fink & Neubauer, this vol.; Neubauer, Fink, & Schrausser, 2002; Neubauer, Grabner, Fink, & Neuper, 2005). Furthermore, a recent review suggested that this inverse relation is most likely to be observed in the frontal cortex (Neubauer & Fink, 2009). This inverse relation has been interpreted to mean that intelligence involves a more efficient use of cortical resources during task performance—and is therefore referred to as the neural efficiency hypothesis. These findings suggest that gains in fluid intelligence as a function of WM training should be localizable in the prefrontal cortex and that they may correlate inversely with brain activation during performance on tasks that recruit fluid intelligence.

Working Memory, Fluid Intelligence, and Creativity

Given that WM training can boost fluid intelligence, coupled with the observation that variations in fluid intelligence are correlated with activation in the prefrontal cortex, Vartanian et al. (2013) recently conducted a study to test the hypothesis that WM training could be used to enhance neural efficiency in the prefrontal cortex in the course of creative problem solving. For creative problem solving, they opted to use a divergent thinking paradigm. This decision was made for three reasons. First, it is known that divergent thinking loads heavily on fluid intelligence (Nusbaum & Silvia, 2011), making it likely that boosting fluid intelligence by WM training will be advantageous for divergent production. Second, previous fMRI and neuropsychological studies of divergent thinking have pinpointed the lateral prefrontal cortex as a key region for solution generation (Goel & Vartanian, 2005; Miller & Tippett, 1996). Recall that this same region is viewed as a major hub for fluid intelligence in the brain (Duncan et al., 2000; Gray et al., 2003). Finally, Fink et al. (2009) had developed an experimental design for administering the alternate uses task (AUT) in the fMRI scanner that could be reemployed in Vartanian et al.’s (2013) study, with minor modifications.

Furthermore, based on recommendations offered in previous reviews of the cognitive (brain) training literature (Klingberg, 2010; Morrison & Chein, 2011), our laboratory implemented certain methodological features. First, whereas the experimental group trained on the n-back task, we employed an active (rather than passive) control group that trained on an easy four-choice reaction-time (RT) task not expected to load on WM. Second, the participants in the experimental (N = 17) and control (N = 17) conditions were matched for sex and age. Finally, the target task used in the scanner was different from the task used for training, enabling a test of transfer effects.

In the beginning of the experiment all participants were tested on one of two versions (odd or even) of RAPM (see Jaeggi et al., 2008). There was no difference in average baseline RAPM scores between the experimental and control groups. Then, whereas the experimental group trained on three separate days on the 2-back and 3-back tasks (in alternating blocks within the same session), the control group trained on three separate days on an easy four-choice RT task. The results demonstrated that, for the experimental group, performance improved across the three training sessions. We attributed this improvement to a gain in WM capacity. In contrast, and as predicted, performance was at ceiling across all three sessions for the control group. Following training, all participants were tested on the version of RAPM not administered to them at baseline. We computed post-pre RAPM scores to calculate gain in fluid intelligence. The results demonstrated that whereas there was significant gain in fluid intelligence in the experimental group, no gain was observed in the control group. In summary, our results demonstrated that repeated training on the n-back task boosted (a) WM capacity and (b) fluid intelligence.

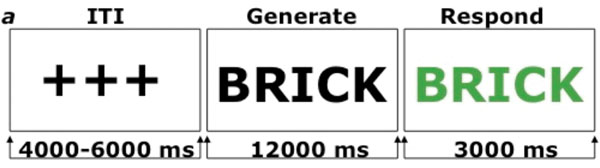

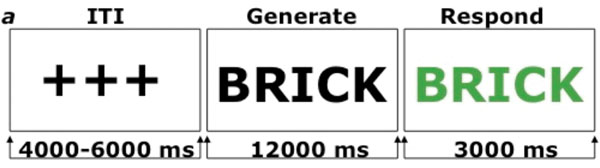

Next, to investigate the transfer of gains in fluid intelligence to divergent thinking, we administered the AUT in the fMRI scanner. The AUT was modeled after Fink et al. (2009) (figure 12.1). The task was presented in two blocks. In the uses block participants were presented with names of common objects (e.g., fork) and instructed to think of as many uses for them as possible. In the characteristics block participants were instructed not to generate uses, but to recall physical features characteristic of the presented object instead.

Figure 12.1

Task structure for alternate uses task (Vartanian et al., 2013). ms = milliseconds. Participants were instructed to generate uses of objects (see text).

Here the focus will be on the most relevant behavioral and fMRI findings. First, contrary to our prediction, gains in WM capacity and fluid intelligence did not transfer to superior performance on the divergent thinking task. Second, confirming our prediction, generating uses was correlated with significantly lower activation in right ventral lateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) in the experimental than control group (figure 12.2). Third, gain in fluid intelligence mediated the link between training and activation in VLPFC, suggesting a mechanism linking WM training to neural function in a target task. The results of our study (Vartanian et al., 2013) demonstrate that WM training is correlated with neural efficiency in the brain during divergent thinking. Furthermore, they also reinforce the role of the lateral prefrontal cortex as the nexus where WM, fluid intelligence, and creativity intersect—at least in the case of divergent thinking.

Figure 12.2

Impact of working memory training on neural function. Lower activation in right ventral lateral prefrontal cortex in participants who trained on the n-back task compared to the control group during the alternate uses task (see text).

Fostering Creativity

Based on a componential view of creativity, the focus of this chapter has been to demonstrate that the neural bases of creativity can be influenced by boosting WM and fluid intelligence—two of its components. However, tracking neural efficiency is one of several possible methods whereby neuroscientific evidence can be used to measure improvements in creativity and to use that knowledge to optimize training regimens to enhance it. For example, Fink and Neubauer (this vol.) review important studies in which computerized divergent thinking exercises were used for training creativity, addressing the research question of how brain activity may change as a function of creative thinking training. They found that the trained participants exhibited stronger task-related synchronization of frontal alpha activity than the control group. Such synchronization suggests that training may have served to make trained participants more focused on relevant aspects of the task. They also studied the impact of interventions (e.g., exposure to others’ ideas) on creative production. Not only was this procedure effective in fostering creativity, but intervention was also reflected in activation in a network involving posterior brain regions known for their role in semantic information processing. Here, the simultaneous use of multiple imaging modalities to investigate whether increases in neural efficiency (by reductions in the BOLD response) are correlated with greater activity as measured by EEG would appear promising (see Fink et al., 2009).

Perhaps most promising is that neuroscience may help track transfer from creativity training to other noncreative tasks. For example, Forgeard, Winner, Norton, and Schlaug (2008) have shown that music training can benefit performance on activities distantly related to music, such as verbal ability and nonverbal reasoning. It is possible that such transfer is facilitated to the extent that the trained and output tasks recruit overlapping cortical regions, despite differences in surface features. In this sense, neuroscientific data can help elucidate the underlying mechanisms that may facilitate transfer not only from component processes to creativity, but from creative tasks to distant activities.

References

Amabile, T. A. (1985). Motivation and creativity: Effects of motivational orientation on creative writers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 393–399.

Amabile, T. A. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review (September): 77–87.

Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W., & Poldrack, R. A. (2004). Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 170–177.

Barch, D. M., Braver, T. S., Nystrom, L. E., Forman, S. D., Noll, D. C., & Cohen, J. D. (1997). Dissociating working memory from task difficulty in human prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia, 35, 1373–1380.

Buschkuehl, M., Jaeggi, S. M., & Jonides, J. (2012). Neuronal effects following working memory training. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2S, S167–S179.

Cattell, R. B. (1963). Theory of crystallized and fluid intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 54, 1–22.

Deary, I. J., Penke, L., & Johnson, W. (2010). The neuroscience of human intelligence differences. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 11, 201–211.

Duncan, J., Seitz, R. J., Kolodny, J., Bor, D., Herzog, H., Ahmed, A., et al. (2000). A neural basis for general intelligence. Science, 289, 457–460.

Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Benedek, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2006). Divergent thinking training is related to frontal electroencephalogram alpha synchronization. European Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 2241–2246.

Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Benedek, M., Reishofer, G., Hauswirth, V., Fally, M., et al. (2009). The creative brain: Investigation of brain activity during creative problem solving by means of EEG and fMRI. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 734–748.

Fink, A., Grabner, R. H., Gebauer, D., Reishofer, G., Koschutnig, K., & Ebner, F. (2010). Enhancing creativity by means of cognitive stimulation: Evidence from an fMRI study. NeuroImage, 52, 1687–1695.

Fink, A., Koschutnig, K., Benedek, M., Reishofer, G., Ischebeck, A., Weiss, E. M., et al. (2010). Stimulating creativity via the exposure to other people’s ideas. Human Brain Mapping, 52, 1687–1695.

Forgeard, M., Winner, E., Norton, A., & Schlaug, G. (2008). Practicing a musical instrument in childhood is associated with enhanced verbal ability and nonverbal reasoning. PLoS ONE, 3, e3566.

Gilhooly, K. J., Fioratou, E., Anthony, S. H., & Wynn, V. (2007). Divergent thinking: Strategies and executive involvement in generating novel uses for familiar objects. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 611–625.

Goel, V., & Vartanian, O. (2005). Dissociating the roles of right ventral lateral and dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex in generation and maintenance of hypotheses in set-shift problems. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 1170–1177.

Gray, J. R., Chabris, C. F., & Braver, T. S. (2003). Neural mechanisms of general fluid intelligence. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 316–322.

Hempel, A., Giesel, F. L., Caraballo, N. M. G., Amann, M., Meyer, H., Wüstenberg, T., et al. (2004). Plasticity of cortical activation related to working memory during training. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 745–747.

Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Perrig, W. J. (2008). Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105, 6829–6833.

Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Shah, P. (2011). Short- and long-term benefits of cognitive training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 108, 10081–10086.

Jung, R. E., & Haier, R. J. (2007). A Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of intelligence: Converging neuroimaging evidence. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30, 135–187.

Kim, K. H. (2005). Can only intelligent people be creative? Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16, 57–66.

Klingberg, T. (2010). Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 317–324.

Li, S. C., Schmidek, F., Huxhold, O., Rocke, C., Smith, J., & Lindenberger, U. (2008). Working memory plasticity in old age: Practice, gain, transfer, and maintenance. Psychology and Aging, 23, 731–742.

McNab, F., & Klingberg, T. (2008). Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 103–107.

McNay, E. C., McCarty, R. C., & Gold, P. E. (2001). Fluctuations in brain glucose concentration during behavioral testing: Dissociations between brain areas and between brain and blood. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 75, 325–337.

Miller, L. A., & Tippett, L. J. (1996). Effects of focal brain lesions on visual problem-solving. Neuropsychologia, 34, 387–398.

Morrison, A. B., & Chein, J. M. (2011). Does working memory training work? The promise and challenges of enhancing cognition by training working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 18, 46–60.

Neubauer, A. C., & Fink, A. (2009). Intelligence and neural efficiency. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 33, 1004–1023.

Neubauer, A. C., Fink, A. & Schrausser, D. G. (2002). Intelligence and neural efficiency: The influence of task content and sex on the brain–IQ relationship. Intelligence, 30, 515–536.

Neubauer, A. C., Grabner, R. H., Fink, A., & Neuper, C. (2005). Intelligence and neural efficiency: Further evidence of the influence of task content and sex on the brain-IQ relationship. Cognitive Brain Research, 25, 217–225.

Nusbaum, E. C., & Silvia, P. J. (2011). Are intelligence and creativity really so different? Fluid intelligence, executive processes, and strategy use in divergent thinking. Intelligence, 39, 36–45.

Owen, A. M., Hampshire, A., Grahn, J. A., Stenton, R., Dajani, S., Burns, A. S., et al. (2010). Putting brain training to the test. Nature, 465, 775–778.

Plucker, J. A., & Renzulli, J. S. (1999). Psychometric approaches to the study of human creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 35–61). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Poincaré, H. (1913). The foundations of science. Lancaster, PA: Science Press.

Ramsden, S., Richardson, F. M., Josse, G., Thomas, M. S., Ellis, C., Shakeshaft, C., et al. (2011). Verbal and non-verbal intelligence changes in the teenage brain. Nature, 479, 113–116.

Renzulli, J. S. (1986). The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for creative productivity. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 53–92). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Richmond, L., Morrison, A., Chein, J., & Olson, J. R. (2011). Older adults show improved everyday memory and attention via a working memory training regime. Poster presented at Annual Meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Boston, MA.

Schlaug, G., Forgeard, M., Zhu, L., Norton, A., Norton, A., & Winner, E. (2009). Training-induced neuroplasticity in young children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 205–208.

Sligh, A. C., Conners, F. A., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, B. (2005). Relation of creativity to fluid and crystallized intelligence. Journal of Creative Behavior, 39, 123–136.

Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2008). Increasing fluid intelligence is possible after all. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105, 6791–6792.

Vartanian, O., Jobidon, M-E., Bouak, F., Nakashima, A., Smith, I., Lam, Q., & Cheung, B. (2013). Working memory training is associated with lower prefrontal cortex activation in a divergent thinking task. Neuroscience, 236, 186–194.

Vartanian, O., Martindale, C., & Matthews, J. (2009). Divergent thinking is related to faster relatedness judgments. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3, 99–103.

Wager, T., & Smith, E. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of working memory: A meta-analysis. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience, 3, 255–274.

Weisberg, R. W. (1999). Creativity and knowledge: A challenge to theories. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 226–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.