13

The Means to Art’s End: Styles, Creative Devices, and the Challenge of Art

On the surface, the visual characteristics of artworks are similar to other objects in our surroundings. They may be described in terms of basic visual features such as shape, complexity, symmetry, color, and texture. However, people respond to and experience artworks in a different way. Although social factors certainly contribute to the special status of artworks (Gombrich, 1999), psychological factors play an important role as well. An artwork, unlike other objects in the environment, does not have a specific practical function—a brush paints, a spoon feeds, and a box holds; it may be argued that a painting is merely viewed. In this chapter, we argue that art does other things, although things that are more psychological than practical. Artworks, through specific means that artists employ, affect the viewer psychologically in a special way: they challenge and enlighten as well as pique and seize the interest of perceivers. This is made possible by creative means that artists have discovered and developed throughout the history of human art making.

Since Fechner’s (1876) early studies, the psychology of aesthetics and the arts has suggested this special function of art. In this chapter, we provide an in-depth examination of the specific techniques and styles—the creative devices—that artists use to create artworks that not only correspond to the way we perceive and interpret the world (e.g., Gombrich, 1960; Zeki, 1999), but also challenge the psychological mechanisms that allow us to respond adaptively to the world. This perspective demands an examination into both sides of the experience of art, namely, creativity and aesthetics—what the artist does and what the viewer experiences. This interface is central to the special quality of art objects.

The way that an artwork challenges a perceiver depends on which aspect of cognitive processing is involved. Every creative device that an artist employs impresses on the viewer in a particular manner and affects specific psychological mechanisms—shape perception, object recognition, speed of information processing, implicit memory integration, interpretation and meaning-making, emotional reactions, and aesthetic judgments. To clarify these dynamics, recent conceptualizations of the aesthetic experience of art have placed particular emphasis on the different phases of art processing and corresponding psychological mechanisms (e.g., Chatterjee, 2003; Leder, Belke, Oeberst, & Augustin, 2004; Tinio & Leder, 2009). One approach, proposed by Leder et al. (2004), describes five stages of aesthetic experiences. During the early stages of aesthetic experiences, low-level visual features (e.g., symmetry) and modulating factors (e.g., familiarity) are processed. The perceiver’s art-related knowledge becomes influential during the later stages, where the content and style of an artwork are determined and it is interpreted and evaluated. At any point during the process of art-viewing, different techniques and specific aspects of an artist’s style could affect the outcome of the aesthetic experience—whether to enlighten us, pique our interest, or challenge how we normally see the world.

As part of their creative toolbox, artists have techniques that produce specific outcomes. The expression of these outcomes is, however, a process made complicated by a variety of factors. The very experience of art itself is modulated by the dynamic interplay between the characteristics of the art object (Kreitler & Kreitler, 1972) and its perceiver (Reber, Schwarz, & Winkielman, 2004), and the context in which this interplay is taking place. Another complicating factor is that similar techniques may be applied to different types of art, such as the juxtaposition of objects in both painting and photography. However, differences exist in their exact application and in the nature of their effects on the aesthetic experience. To account for such differences, which are often very subtle, we discuss artists’ techniques and styles across various visual arts media, noting the differences as well as the similarities. It is important to note, however, that these discussions are also relevant to other nonvisual artistic media.

The approach of looking at art in terms of the challenges that it poses for the viewer is consistent with recent perspectives that endorse a broader conceptualization and examination of aesthetic experiences. For example, Silvia (2005, 2009) argued that aesthetics research is still closely tied to the tradition of Fechner (1876) and Berlyne (1971). As a consequence, aesthetics studies have focused mainly on liking and preference. According to Silvia, aesthetics should go beyond these positive responses and account for a broader range of aesthetic experiences, even negative ones such as disgust, anger, and confusion. Thus, the perspective in this chapter, which focuses on the psychological challenges posed by art, is consistent with this broader take on aesthetic experiences.

In our discussion of the challenge of art, we refer directly to studies of various psychological phenomena. At the same time, we also introduce new issues and propose novel concepts (e.g., the photographic peak-shift effect) that we believe are amenable to psychological testing and are particularly suited for, and relevant to, experimental and neuroscientific studies. In the next sections, we describe the following creative devices and their corresponding effects on specific aspects of aesthetic processing: line depiction and object recognition; figure-ground, juxtaposition, and visual continuation; the peak-shift effect and visual emphasis; sharpness of depiction and gaze patterns; framing and visual balance; physical orientation and size of an artwork and access to its content; and abstraction and speed of processing.

Line Depiction and Object Recognition

Line depiction is an artistic device that provides a definite psychological challenge to perceivers. This technique takes advantage of how humans process lines during the process of object recognition. Many theories of visual perception have claimed that object recognition proceeds through a series of representations that are constructed from the flow of visual information emanating from the environment. This process begins with the entry of photons into the eyes and results in rich perceptual representations occurring deep in the visual areas of the brain. David Marr (1982) attempted to systematically account for the sequential nature of visual perception by proposing a stage model that included very specific mechanisms and processes. As a starting point, he claimed that the visual system first analyzes the light distribution on the retina with the goal of identifying interesting visual areas. This process occurs via a filter that identifies areas of the image with transitions in contrast and where surfaces come together or overlap. Interestingly, and relevant to line depiction as a creative device, when this process is simulated in an artificial system, it produces scattered lines that are distributed over the image area and represents segments of the image that mark edges of objects as they appear in the real world. From this, Marr and others studying visual perception (e.g., Biederman, 1987) discussed how these kinds of lines could be the basis for object recognition. The researchers developed theories of object recognition based on the fundamental concept of basic elements, such as line segments, serving as input into the visual system and eventually resulting in a reconstruction of the visual environment.

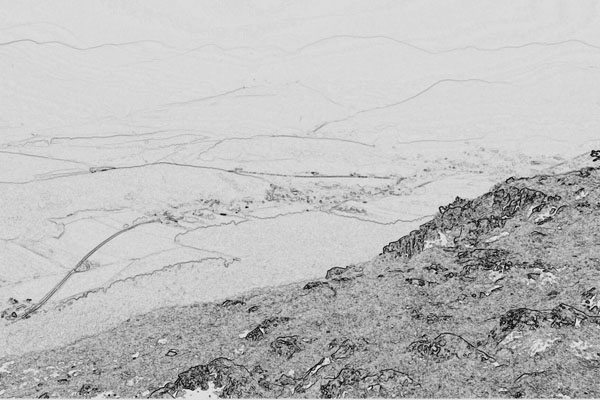

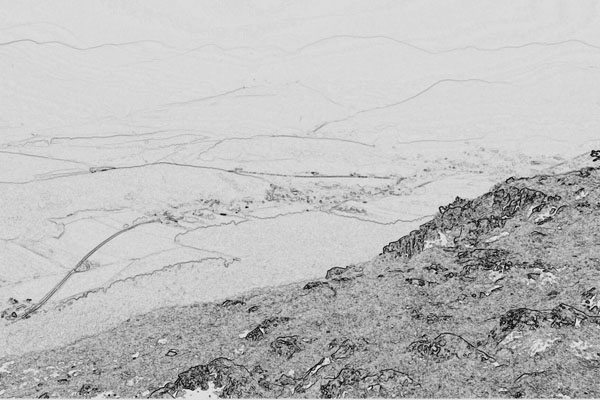

If lines are the basic ingredients of vision, then it follows that perceiving objects depicted as line drawings should take place relatively easily; in fact, early studies (e.g., Biederman & Cooper, 1991) suggested that objects depicted using line drawings are, at the very least, not more difficult to perceive than the same objects depicted using visually richer media such as photographs. This is not surprising because of the importance of lines in major theories of vision (e.g., Marr, 1982). Many recognition skills, however, cannot be accomplished well from line representations. For example, figure 13.1 shows a transformation of a photograph to a line drawing using a line-extraction filter from a commercial image-processing software. Although the original scene can be identified based on the line depiction, it requires some effort—visual elements need to be combined to discern the boundaries of objects and major areas of the image in order to allow the proper identification of the scene. As a comparison, figure 13.2 is a photograph version of the same scene. It is apparent that scene information in the photograph is much richer and much easier to access than in the line depiction.

Figure 13.1

Landscape photograph converted to a line depiction (by P. L. Tinio).

Figure 13.2

Normal landscape photograph (by P. P. L. Tinio).

Face perception is one of the best examples of the effects of line drawings on perception. For example, it has been shown that line drawings showing faces are recognized as people but not as specific persons. Davies, Ellis, and Shepherd (1978) were the first to systematically study the difficulty of recognizing facial identities from line drawings of faces. Their research was motivated by the question of how images of faces could be produced in a way that facilitates the recognition of crime suspects and fugitives. The study compared people’s ability to recognize simplified or detailed line drawings that were produced by accurately tracing the lines from corresponding original photographs. Compared to the photographs, for which accuracy of recognition was 90 percent, the accuracies for the line drawings were 47 percent for the detailed and 23 percent for the simple versions. This is evidence that line drawings are poor representations of facial identity. Leder (1996) conducted a series of studies with the goal of understanding why facial recognition is more difficult with line drawings. He found that the identification of factors such as age and attractiveness, which are typically performed with very little effort, were disrupted. Moreover, the configuration of facial features—information considered particularly important for face recognition—could not be accessed from line drawings.

From these studies, it is clear that the recognition of objects and faces suffers when they are depicted using lines. Line depictions also pose a challenge in perceiving artworks. One reason is that line depictions lack the shading information that is essential for object recognition (Davies et al., 1978). Shading provides cues—such as texture and depth—that are necessary for visual perception in general, and object recognition in particular. Artists manipulate shading both to facilitate and to hinder perception. Bruce, Hanna, Dench, Healey, and Burton (1992) have found that adding detail to the internal areas of line drawings eases their recognition. Artists know about these effects. Drawings using pen, charcoal, or pencil contain mainly lines. These are often handled using hatching to produce areas of texture that facilitate recognition. A close look at celebrated engravings, such as those by Albrecht Dürer, shows that they are rich with “fill” information.

These techniques are central to an artist’s creative arsenal and they are basic skills that must be mastered in the first years of art school or professional apprenticeship. A source of evidence that artists facilitate, perhaps implicitly, object recognition in their artworks comes from the field of neurostatistics. Graham and Redies (2010) examined the image statistics of line drawings as a class of artworks. They used a large set of images and analyzed the Fourier power spectra of various classes of objects. Their analyses showed that the slope of the distribution—an indicator of the relationship between detail and gross areas of an image—for portrait drawings was more similar to the statistical values found for photographs of real-world scenes than, for example, photographic portraits. This suggests that artists have implicit knowledge that allows them to produce drawings with visual statistical characteristics that resemble visual stimuli for which the human visual system is presumably best adapted—natural scenes, which are the type of environments from which humans evolved.

In contrast to the types of depictions that feature techniques that attempt to ease recognition, some artworks seem to have been made to hinder recognition, thus challenging the perceiver. Andy Warhol’s portrait paintings are good examples of this. Some of his most recognized portraits were of Marilyn Monroe, which were typical of his style of painting. These portraits combine the characteristics of line drawings (with the outline defining the shape, but lacking in internal details) and the characteristics of photographic negatives. It is known that facial identities in photographic negatives are difficult to recognize (Phillips, 1972). Warhol’s novel use of color further disrupts aesthetic processing. Thus, the aesthetic challenges associated with such artworks are immense.

Figure-Ground, Juxtaposition, and Visual Continuation

The juxtaposition of objects—or the partial superimposing of an object over another causing the partial occlusion of the second object—is another means by which artists influence the aesthetic response of the perceiver. This creative device is an exploitation of one of the most fundamental features of visual perception: the ability to distinguish an object from its background, which is also referred to as the figure-ground phenomenon first described by the Gestalt psychologists (e.g., Koffka, 1935; Rubin, 1915/1958). Being able to separate an object of interest from its surroundings is a prerequisite for the identification or recognition of that object. The significance of this human ability is further evidenced by recent studies that have shown that figure-ground separation occurs even in the absence of directed attention to an object (Kimchi & Peterson, 2008), which also suggests the adaptive value of being able to separate an object from its surroundings.

The Dutch artist M. C. Escher takes advantage of the human predisposition to separate figure from ground. In his works, Escher creates what may be considered visual illusions in which visually separating one object from another, or an object from its background, becomes difficult. These works challenge perceivers by disrupting the visual perceptual responses that have been adapted to their usual environment. Escher’s Sky and Water II, a grayscale woodcut, depicts birds on the top half and fish on the bottom half of the frame. The meeting of the two types of figures on the water line poses a figure-ground challenge: effort is required to distinguish the birds from the fish, and the perceiver is left with the task of alternating attention between the two groups of objects. The manipulation of figure-ground—whether done consciously or unconsciously—is central to Escher’s style, and this may be the underlying reason for the engaging quality of his artworks.

Artists can use juxtaposition for visual effects in another way: through the continuation or discontinuation of the form of an occluded object. Arnheim (1954) provided the following example: “The segment of a disk will or will not appear as a part of a circular shape depending on whether the curvature, at the points of interruption, suggests continued extension or an inward turn toward closure” (p. 122). He presented a detailed discussion of the effects of juxtaposition on the perception of artworks. Arnheim believed that juxtaposition accentuates and makes the visual relationship among objects more dynamic. Separation of figure from ground through juxtaposition leads to an emphasis of one object over another—a visual hierarchy; although this is not always the case, as it could also be that there is an alternation of juxtaposition between the various elements of two objects within an image. An example of this would be a drawing of two snakes that are intricately intertwined; here, which snake occludes and which is occluded depends on at which part of the drawing one is looking.

In photography, the figure-ground relationship is also manipulated in specific ways to produce effects that challenge the perceiver. For example, the type of camera lens used to create a photograph affects the perceived relationship between the figure and background or between any number of objects occupying different visual planes within the image frame. Camera lenses with “long” focal lengths (telephoto lenses), in contrast to those with “short” focal lengths (wide-angle lenses), compress the image, and as a result, objects in different visual planes appear closer to each other (London & Upton, 1998), an effect similar to that produced by the side mirrors of cars where objects in the mirror appear closer than they actually are. In this sense, the photographer could produce certain effects by exploiting the relationship among objects in terms of depth and perspective. Perceivers are challenged because what they are seeing in a photograph does not correspond to how they typically see the world.

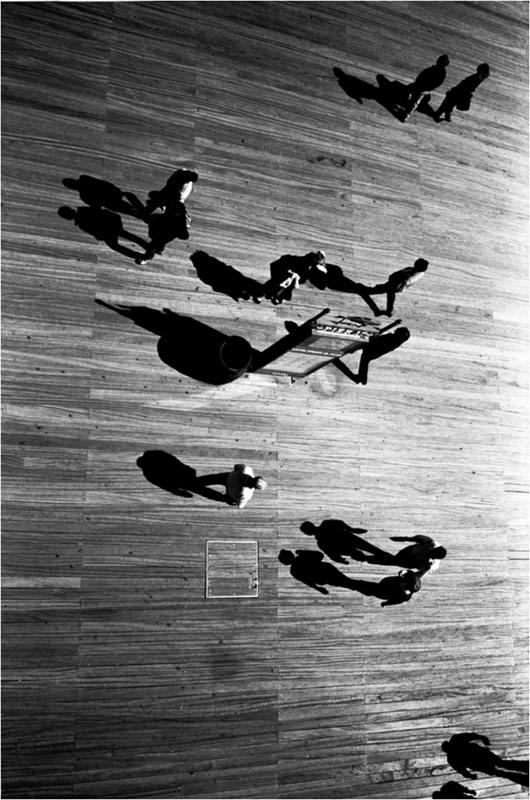

Juxtaposition of visual elements is prevalent in photography, and its effects on perception and the aesthetic experience are similar to its effects and experience in other art media. It is, however, important to note that overlapping in photography has effects that are specific to the medium. The uniqueness of the photograph as an image lies in its ability to capture a real scene, a “frozen” moment of an actual object in its environment. Although a photograph distorts how its referent is perceived (Latto & Harper, 2007), perceivers nonetheless expect it to have sufficient accuracy of depiction and represent an actual moment in time. Many photographs capture dynamic and multilayered scenes with objects moving in different directions. A photograph of such a scene will almost certainly have overlapping objects or moving objects with overlapping trajectories—with each object on a course of its own. Such an image is particularly engaging. Palmer, Gardner, and Wickens’s (2008) recent study on the influence of the position and direction of an object on the spatial composition within a frame provides evidence of why this is the case. They found a preference for images depicting objects that are facing their direction of movement and that people have an inward bias—inward referring to objects that face into as opposed to out of the frame. For example, an image with an object facing left and positioned on the right side of the frame is preferred to the same object on the left side of the frame—the former object is inward facing while the latter is outward facing. This effect was found in a two-alternative forced-choice task and in an adjustment task in which participants placed objects on a horizontal line. Palmer et al. also employed a photograph production task where participants took photographs of objects. In the latter task, participants positioned objects facing left on the right side of the frame and objects facing right on the left side of the frame.

Based on such results, a person viewing an image depicting objects with different movement trajectories must juggle simultaneous expectations—an expectation corresponding to each moving object. Photographs have an element of truthfulness that other artistic media do not have. As a result of this, there is a natural tendency to want to know what happened before the depicted moment and to desire the completion of an action—an expectation of where a moving object is headed. Participants taking photographs in Palmer et al.’s (2008) study provided objects the space in which to move. People do not have similar expectations of depicted objects that do not have an implied direction—forward-facing objects, for instance. In fact, Palmer et al. found that participants preferred forward-facing objects to be positioned near the center of a frame.

For photographs with multiple objects, the different trajectories of the various objects overlap, and viewers, because of their expectations, must presumably expend effort to engage with the objects aesthetically. The result is deep engagement with the photograph; compare this to a still-life photograph of a flower. The dynamism and interestingness of a photograph with moving objects is thus rooted in the viewer’s attempt to realize an expectation and a completion of a visual aesthetic narrative, which demands cognitive effort and facilitates deep engagement. Figure 13.3 is an example of a photograph that has a high demand for a completion of a visual aesthetic narrative. The viewer must constantly navigate between the figures that compose a network of overlapping trajectories.

Figure 13.3

Photograph illustrating objects with overlapping trajectories and completion of a visual narrative (Untitled by P. P. L. Tinio).

What we have learned from the previous examples is that figure-ground manipulation and overlapping could influence perceivers in several ways and that artists could exploit this to entice and to challenge the perceiver. An object can be visually emphasized more than another. A qualitative dominance hierarchy between objects could also be produced, with some objects being perceived as dominant and some as submissive. Thus, the affective reactions of perceivers are highly susceptible to the effects of such manipulations. Arnheim (1954) provided the example of photographing a prisoner from either inside or outside his prison cell. As one could imagine, the two views would elicit different reactions from the perceiver. Artists could also employ juxtaposition to force perceivers of their artworks to alternate their focus between two objects that are entwined so as to engage them and enhance the dynamism of the artwork. Alternating between two aspects of an artwork could also lead to an increase in the ambiguity of the artwork, leaving perceivers uncertain as to how to approach an aesthetic encounter—their challenge is to resolve (or at least tolerate) the visual ambiguity. Juxtaposition may be used to create mystery where the main subject or primary action in a painting is occluded and the viewer must engage with the painting using the limited information available. Finally, juxtaposition in photographs of moving objects creates a demand for a completion of a visual aesthetic narrative where the different object trajectories each compete for attention and demand a resolution.

Peak-Shift Effect and Visual Emphasis

As much as artists have at their disposal techniques that slow, disrupt, or conceal a depicted object, they also have ways of isolating, highlighting, and exaggerating particular characteristics of an object. According to Ramachandran and Hirstein (1999), these latter techniques are exemplified by the peak-shift effect in art, which is one of the main underlying principles behind the human fascination for art. This effect also corresponds specifically to neural response patterns: amplification of form leads to a corresponding amplification of neural responses to such form. The caricature (see Gombrich, 1960, for a historical perspective) is one manner of artistic depiction that reflects the peak-shift effect. Caricature artists identify the most distinct aspects of a person’s physical appearance and amplify them. For example, the television host Jay Leno’s chin, when compared to chins of most people, is distinctively large and elongated. A caricature artist drawing his face would accentuate—by further enlargement and elongation—this already distinctive and idiosyncratic feature. Artists thus employ the peak-shift effect—deliberately or not—to emphasize particular aspects of their subject.

Ramachandran and Hirstein (1999) argued that caricature in one form or another is present in most art and is not limited to form space (i.e., the contour or shape of a visual object), but may also apply to other visual elements such as color. This would be the case with an artist who exaggerates the blueness of a blue sky or a blue ocean.

The peak-shift effect in aesthetics has been described primarily in the context of the traditional arts such as painting. Photography, however, is an art medium in which the peak-shift effect is highly prevalent. At the same time, it is a medium in which the effect is difficult to employ deliberately for the reason that most photographs, especially those depicting people, are created in mere hundreds of seconds (the short exposure time is necessary to “freeze” even the smallest of movements). Ramachandran and Hirstein (1999) described the peak-shift effect concerning body postures in terms of the following process: first, a given body posture is subtracted from an average of body postures (posture space) that a person has seen during a lifetime; second, the resulting difference is then amplified (i.e., exaggerated). From this an effect is produced where a less-than-average posture becomes even more distinct, but still resembles a known or even regularly observed posture.

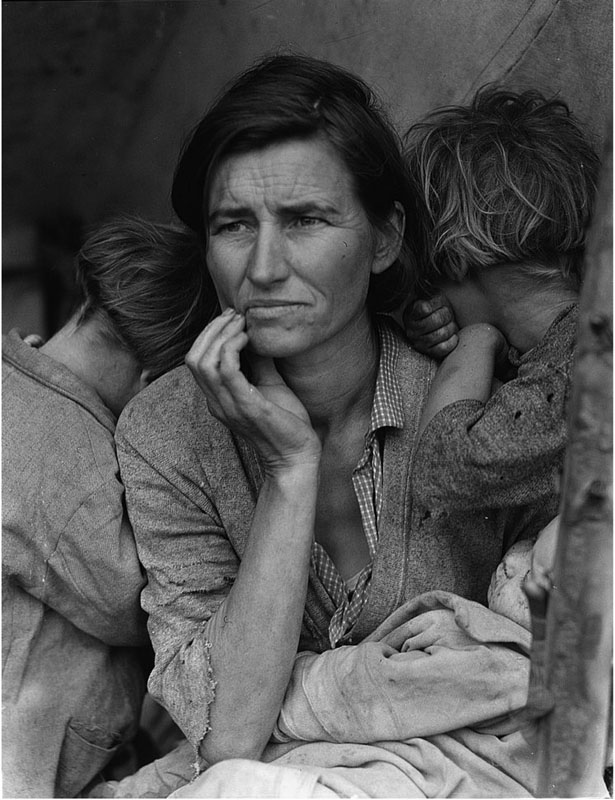

We describe the peak-shift effect in photography as the process of capturing in an image a less-than-average body position, nonverbal gesture, or facial expression. This results in a powerful image—with universal appeal—that has more than average ability to affect the viewer. The most compelling documentary photographs are the best examples of this. As an example, consider Dorothea Lange’s iconic photograph Migrant Mother (figure 13.4), made during the Great Depression, which represented the plight of poor migrant workers and their struggling families in the United States (Rosenblum, 2007). How could a single image have such a powerful effect? We argue that photography produces images that are optimal for evoking a strong response from the viewer through a photographic peak-shift effect.

Figure 13.4

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-9058-C.

The photographic peak-shift effect is rooted in the attributes of photography that distinguish it from other art media. First, cameras have the ability to freeze moments in time, especially moving objects, even when the movements are so brief that they are rendered nearly imperceptible to people. Second, photography is typically employed to document people in special situations (birthday parties and family gatherings), newsworthy occurrences (a political protest), and significant historical events (war). Thus, some body postures, nonverbal gestures, facial expressions, and movements, because they are imperceptible and rare, do not become part of the posture space, which comprises canonical representations of these human body states; however, although imperceptible and rare, they still resemble, even if only slightly, something in people’s memory. In addition to the two previous reasons (imperceptibility and rarity), photography has a distinct quality that is absent in other visual arts media: the realism of content—photographs involve real people and their movement in space situated within real environments.

Lange’s photograph is powerful because it captures a moment in which the mother’s facial expression and nonverbal gesture is at its peak and this is accompanied by the positions of the children. According to the legendary and highly influential photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, “You wait and wait and then finally you press the button—and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something. Later, to substantiate this, you can take a print of this picture, trace on it the geometric figures which come up under analysis, and you’ll observe that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been formless and lifeless” (1952, p. 8). The photographic peak-shift effect explains this decisive moment about which Cartier-Bresson speaks.

Painters and sculptors may rely on prototypical or canonical representations about facial expressions such as sadness and joy and about body postures such as those that reflect aggression and surprise. The photographer, in contrast, exploits peaks in nonverbal behavior that, because of the quickness in which they are expressed, render them imperceptible; photographic images of these peaks, which are more extreme than prototypical or canonical representations, elicit a strong response from the perceiver.

Sharpness of Depiction and Gaze Patterns

An additional visual element controlled by artists is the sharpness (or clarity) with which an object is depicted. Certain art media, such as aquarelle and pastel, produce artworks that have relatively low clarity. In a study examining the relationship between processing fluency and aesthetic preference, Leder (2003) presented participants with two versions of pastel portraits—one with low clarity and the other with moderately high clarity—and one aquarelle portrait that had extremely low clarity. Results showed that the stimuli that were higher in clarity, and thus higher in processing fluency, were preferred more. In this example, clarity of depiction was constrained by the actual choice of art materials.

Photography is another medium where the manipulation of clarity—through variation in sharpness—is highly evident. The nature of this manipulation is closely tied to two things. The first is the manner in which a camera captures an image. As complex as cameras have become during recent years, the essence of picture taking still comes down to the photographer’s regulation of basic camera settings (lens focus, aperture opening, and shutter speed) that influence the sharpness of an image. The second is the characteristics of the perceiver.

For the human visual system, sharpness is related to where we need to look at any given moment. Only a small area—approximately two degrees of visual angle—of the field of vision is in focus. As you move away from this central region to the periphery, sharpness declines dramatically. The eyes must move constantly to scan different areas of the visual field (Rayner, 1998). Thus, when we view a photograph, our eyes must move constantly across the image, fixating on different areas. The photograph (and other static images) is visually interesting and provides the viewer with challenges that are rooted in the difference between the workings of the camera and human vision.

Because of physiological constraints, the mechanics of human vision is fixed—the process of scanning of a visual field is relatively similar across different contexts. This contrasts the wide range of sharpness of depiction across photographs: one photograph could have a very shallow depth of field with sharp focus on only one visual plane; another could have greater depth with more objects from different visual planes in sharp focus. These extremes in sharpness characteristics provide viewers with visual experiences that are similar and yet in some way different from the way they normally perceive the world. Photographs are able to depict real scenes fairly accurately and are thus close to how people see scenes in their daily lives; yet photographs are able to represent sharpness in a way that is very different from what the human visual system is able to achieve. For example, photographs that have extremely high levels of depth-of-field—that is, objects from the foreground to the background of the image are all relatively equally in sharp focus—are extremely unusual in terms of how people normally see the world, because in normal seeing, only a small portion of the visual field is in focus (Rayner, 1998). Thus, to a viewer, extremely sharp images, especially those depicting changing and moving objects, are visual treats. They allow inspection of a dynamic scene in a non-time-sensitive manner; in other words, through photographs, people are able to visually inspect a scene without the need to take into account changes that occur as time passes—the aesthetic experience of a static image is, in a way, time independent.

Framing, Cropping, and Visual Balance

Up to this point, we have discussed techniques that artists use that pose particular challenges to the viewer. These techniques involve manipulation—whether conscious or not—of the most essential aspects of an image typically involving the object (e.g., its sharpness or the juxtaposition of elements) being depicted. Artists, in addition, go to great lengths to control the physical boundaries or edges around the image. Modern imaging techniques, which enable art historians and conservators to analyze the process that an artist goes through to create a work of art, have shown that multiple revisions are often made on the boundaries of an image (see Kirsh & Levenson, 2000).

Controlling the boundaries of an image is particularly important in photography. Taking a photograph involves placing a rectangular frame around a live scene or object and permanently excluding everything outside that frame from the final image. This process of framing is unique to photography. For example, in painting, the artist begins with a blank canvas upon which various layers of marks and depictions are built, usually beginning with an underdrawing where the underlying structure of the final image is partially defined. The painter then continues to build the image. In contrast, the photograph begins with an existing image, which the photographer must refine through a process of selection. (Excluded in this discussion is, of course, photography that involves artificial selection and arrangement of scenes.)

The viewfinder of a camera, acting as a frame, provides a coherent visual organization to a world that actually lacks such organization, thus creating a sequence of representations (Burgin, 1977). The viewfinder thus selects and organizes the raw materials with which the photographer is working. This may be considered as the initial phase for establishing the composition of the image—a process not unlike putting down the underdrawing in a painting. As with other image manipulation procedures, cropping influences the viewer in specific ways. Tinio and Leder (2009), in their taxonomy of image-manipulation procedures, characterize the effects of cropping on the aesthetic experience of the viewer. Cropping is a composition-level manipulation that affects the structure of images. Cropping changes the perceived symmetry, complexity, and overall pictorial balance of images, characteristics that are processed during the early stages of information processing.

Recently, McManus et al. (2011) examined photographic cropping in terms of both how people crop photographs and how people aesthetically evaluate photographs that have been cropped in various ways. Their findings from six psychophysical studies showed that cropping indeed has a strong influence on people’s aesthetic judgments. First, they found that people were consistent in terms of how they cropped different photographs. Second, they showed that some people are better croppers than others. Third, there were differences between the way art experts and nonexperts cropped photographs. These findings serve as evidence that both the act of cropping and the preference for a particular cropping style are not arbitrary. Photographic cropping is indeed a feature of both creative expression and aesthetic experiences.

A photographer’s style may be defined by a preference for (or objection to) the use of cropping to finalize the composition of images. Cartier-Bresson (1952), for instance, vehemently objected to the cropping of his photographs, and believed that cropping leads to a disruption of the balance of a good photograph. Quite the opposite opinion was held by Alexey Brodovich (1961), who believed that cropping helps photographers interpret their photographs in new ways and that it should be employed if it will result in more powerful photographs. In terms of artistic styles related to cropping, these two artists represent the opposite ends of the spectrum, and their adherence to such styles further underscores the importance of cropping as a creative technique.

Physical Orientation and Size of a Work and Access to Content

A completely different kind of framing, one related to the physical orientation of an artwork, has also been used by artists to obtain specific effects. Except for a handful of studies (e.g., Latto & Russell-Duff, 2002), the orientation of an artwork has not been extensively discussed in the aesthetics literature. The manipulation of physical orientation is a very efficient way of influencing how an artwork is perceived. It can also be used as a creative way of posing a challenge to the viewer. The use of this method is prominent in the works of the German painter Georg Baselitz. A dominant feature of Baselitz’s style is the upside-down presentation of his paintings, a method that he has employed since the 1970s. Viewers may notice that this mode of presentation has a dramatic effect on how the contents depicted in the paintings are accessed—that inversion disrupts the processing of content and transforms an image from representative to abstract. Although this claim might seem like an exaggeration, it is in accordance with findings showing that the inverted presentation of faces disrupts their processing—the so-called face inversion effect.

Yin (1969) was the first to assume that inversion would disrupt processing of objects in general, and that this effect would be strongest for the processing of faces. Since his seminal work, studies have revealed the psychological mechanisms underlying the effect: a kind of processing in which both holistic representation and reliance on configural information become unavailable when faces are inverted (e.g., Leder & Bruce, 2000). Baselitz’s inverted artworks therefore target people’s processing of orientation information and their need to know the orientation of up and down (e.g., ground and sky) as they relate to their surroundings. The question remains of how other regularities in our visual environment are disrupted by other atypical orientations of artworks. This question becomes even more complicated when physical orientation interacts with other visual elements such as color, which is the case with some abstract paintings. For example, what would be the effect of disrupting the often-found distribution of brown to blue (representing the transition from ground to sky) that has been identified as an important attribute of landscape images (Oliva & Torralba, 2001)?

Another important physical aspect of artworks is size. Artists make conscious decisions regarding the scale of their artworks relative to content and what they are trying to achieve. Renowned artists have created artworks on a very small scale. Examples include Vermeer’s painting The Lacemaker, which measures approximately 9.6 × 8.3 inches, and some paintings by Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí. The diminutive sizes of such artworks bear no relation to their power to captivate perceivers or to their significance in terms of their place in art history. There are also many examples of artists creating noticeably large artworks. Examples include Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, which measures 138 × 308 inches, and the color field paintings by abstract expressionist artists such as Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman.

The influence of the size of an artwork on aesthetic experiences could also be modulated by what and how content is depicted. In a fascinating study of the influence of an artwork’s size on the aesthetic experience, Pelli (1999) examined the works of Chuck Close, an American painter who creates large-scale works based mainly on dividing the canvas with a grid and filling in each cell of the grid with color. This style of depiction produces visual impressions that depend on a viewer’s distance from the artwork: seen from near, each of the many individual cells is perceived, whereas seen from afar, small groups of cells meld together to form features of a larger image, a classic example of which is the portrait—one of the main aspects of his oeuvre. In several studies, Pelli (1999) directly referenced Close’s artworks when examining the relationship between viewing distance—hence object size—and the perception of an object. Pelli’s results demonstrate that aesthetic experiences are dependent on the sizes of objects; in this case, the size of an artwork is a function of the perceiver’s distance from it—the faces in Close’s artworks are only perceptible from afar.

Abstraction and Speed of Processing

Recent studies have provided evidence of a close relationship between characteristics of visual stimuli and the relative speed with which they can be processed. Visual perception happens so quickly that it is easy to assume that it is an instantaneous process. However, it involves brain activities and physiological processes that require time. Making estimates of the duration of early physiological processes is complicated because there is a strong interaction between visual processes and memory representations. As complex as visual perception is, it is a highly efficient process. Thus, even minimal visual information reaching the retina is interpreted, which results in fast percepts. Oliva and Torralba (2001) have shown that representations of what an image depicts rely on global image features. For example, an image with a light upper portion and a dark lower portion is perceived as depicting a landscape, and that an image with multiple green elements is perceived as depicting a forest. Such inferences have been shown to have good validity. Moreover, Torralba (2009) found that the content of an image could be extracted even if the resolution is as low as 32 × 32 pixels. Results of studies employing tachistoscopic image presentation—allowing millisecond stimulus presentation—have shown adequate recognition performance, with results showing that when images are flashed briefly into the left and right visual fields, perceivers can detect animals within 120 milliseconds (Kirchner & Thorpe, 2006) and faces within 100 milliseconds (Crouzet, Kirchner, & Thorpe, 2010).

As important as temporal factors are to visual perception, there is a lack of systematic studies of the time frame of art perception. Leder et al. (2004) attempted to account for the time frame of aesthetic experiences in their model of aesthetic experiences. Using this model as a foundation, Augustin, Leder, Hutzler, and Carbon (2008) recently examined the time it takes to process an artwork’s content or style. Their results showed that artistic style, such as that of van Gogh, was processed quickly (after 50 ms); but not as quickly as what was depicted in the image. Bachmann and Vipper (1983) also examined the time course of aesthetic experiences by presenting artworks that featured six highly distinctive artistic styles. Results showed that the longer participants viewed an artwork, the more they tended to perceive it as more involved, simple, regular, and precise. These studies shed light on the time course of aesthetic experiences of visual art. However, they do not help determine the process by which an artwork—and its specific techniques and styles—directly affect the time frame of a viewer’s aesthetic experience.

In art perception, certain devices that artists use have an impact on speed of processing. A good example is cubism, an artistic style that has been shown to influence the time frame of aesthetic experiences. Cubist paintings have the effect of slowing down information processing. In cubism, depicted objects are deconstructed into abstracted forms. Common to cubist paintings is the breakdown of an object into basic geometric elements, which interestingly resemble the forms in Biederman’s (1987) theory of object recognition in which objects are represented as geons—simple forms such as cylinders and cones. In cubist paintings, the basic elements are then recombined to simultaneously depict multiple views, thus providing a kind of integrated and visually dynamic metarepresentation of an object. This mode of depiction involving the abstraction of image content and depiction of multiple views has been shown to slow the process of object recognition (Hekkert & van Wieringen, 1996). Recently, Kuchinke, Trapp, Jacobs, and Leder (2009) further explored the aesthetic response to cubist paintings using physiological methods and found that high abstraction in cubist paintings was associated with slower object recognition, more difficult processing, and more negative aesthetic judgments. They also found evidence that ease of processing was related to positive affect. As a creative device, abstraction has a tremendous impact on the time course of aesthetic experiences, and artists can modulate it to elicit positive or negative aesthetic reactions.

Conclusion

Art challenges. It does so in various ways depending on the creative device the artist employs—whether implicitly or explicitly. Each device targets a specific aspect of aesthetic processing. Line depictions hinder object recognition, which runs counter to some theories of visual perception that stress the importance of lines in object recognition (e.g., Marr, 1982). Juxtaposition influences the perception of figure-ground separation. It also suggests visual continuation and creates a dynamic effect when it involves objects with overlapping trajectories—viewers expect objects in motion to have a direction, and perhaps even a destination, that extends beyond the confines of the image. This becomes particularly challenging for viewers because such images demand a completion of a visual narrative. The peak-shift effect provides visual emphasis (Ramachandran & Hirstein, 1999). When applied to photography, the effect breaks free from its dependence on canonical representations stored in memory and involves gestures, postures, and facial expressions that are either so rare or nearly imperceptible that they can be experienced directly only when captured and frozen as a static image. Sharpness of depiction plays with gaze patterns because of the disparity in the way we look at an image of a scene and the way we look at the same scene in actuality. Cropping techniques affect the structure of artworks (Tinio & Leder, 2009). The physical orientation and scale of an artwork affects the way its content is accessed; an upside-down artwork is a different artwork right-side-up, and an artwork seen from near is visually different when seen from afar. Finally, visual abstraction slows information processing as the viewer attempts to determine the identity of the depicted object. The devices that we have highlighted above make up only a subset of what is available, of what has been discovered or developed during the long course of art making by humans.

Considering artworks in this way does have its limitations. Some of the devices, such as visual abstraction and line depiction, and their corresponding psychological effects, such as speed of processing and object recognition, pertain mainly to the early stages of aesthetic processing and only partially address the later stages where higher-order cognitions like meaning-making occur—the essence of the experience of art (Millis, 2001; Russell, 2003; Russell & Milne, 1997). This is not to say that the early stages are unimportant. Quite the opposite: what happens in the earlier stages set the stage for what happens in the later stages and what final outcomes subsequently emerge—an aesthetic evaluation, for instance. Moreover, we have not addressed the interactions among the many devices, which is likely to occur in the real world of art. For example, juxtaposition doubtlessly has an impact on the visual balance of an image, and decreasing the clarity of an image may also have the effect of increasing abstraction. There is also evidence that the effects of multiple image manipulations are additive (Tinio, Leder, & Strasser, 2010). The methodological challenges and conceptual ambiguities resulting from these interactions must be taken into consideration in future research.

Moreover, although our focus here was on the challenge of art, we do not discount the idea that aesthetic experiences involve pleasure. We do believe that some of this pleasure is derived from the resolution of the challenges imposed on the viewer, that an aesthetic experience is sometimes about problem solving—the type of problem determined by the device encountered by the viewer. This is consistent with recent models of the aesthetic experience (e.g., Leder et al., 2004). In the end, we believe that the power of art, its ubiquity in our lives, lies as much in its ability to challenge the way we look at reality as in its ability to represent and even mimic reality. Our approach is consistent with the recent push toward looking at aesthetics more broadly, beyond liking and preference (Silvia, 2005), and more toward the full richness of human experiences.

This approach coincides with developments in the ability to measure psychological responses (e.g., fMRI)—especially aesthetic responses. Thus, there is a correspondence between developments in the conceptualization of aesthetic responses and the use of neuroscientific methodologies. Data from imaging studies could be used to show the unique impact of artworks on viewers. However, neuroaesthetics is still an emerging subfield of aesthetics, and relatively few studies have been conducted on neural specificity associated with aesthetic responses to artworks. More importantly, there is a lack of neuroscientific studies that have examined nonpositive responses to art (Brown, Gao, Tisdelle, Eickhoff, & Liotti, 2011). The question of whether cortical structures that respond to artworks are the same as those that respond to everyday objects remains unresolved and open for examination. Consistent with our analysis of how artworks challenge the viewer is the idea that assessing a wider range of responses increases the possibility of discovering neural areas that are specific to artworks. Such an approach would go beyond simple perceptual responses common to most objects. It would take into account higher-order cognitive processes including meaning-making, art-related interpretations (favorable or not), judgments based on perceivers’ art-related knowledge and experiences, and aesthetic emotions, both positive and negative. This would augment and build on knowledge gained from a century of work in experimental aesthetics, work that has mainly focused on the impact of simple, bottom-up factors on generally positive aesthetic responses (Silvia, 2005).

Looking at art in terms of challenges also provides a direct line between creativity and aesthetics. We believe that this has not been emphasized enough in the literature. Why is a focus on the challenges that art poses to the viewer better at connecting these two sides? Artists’ motivations in creating artworks are not always based on whether viewers will find their creations pleasant; they consider other ways their creations could be received. The viewer’s perspective is analogous to this. A visit to the museum is not just about pleasure, but also about getting interested and engaged, and it may even be about the process of confrontation—between a viewer’s expectations and an artwork that is inconsistent with them. A visit to the museum could also involve exploration and the process of making meaning of an art object, both of which relate to the artist’s perspective while creating the artwork. During aesthetic encounters, art viewers want to learn about the works, know about the motivations of the artists, and connect in some way to the ideas behind the works (Tinio, Smith, & Potts, 2010). The devices that artists use influence the outcomes of these encounters. Thus, looking at how the use of specific artistic devices challenge the viewer would bring creativity and aesthetics—creation and reception—closer to each other.

References

Arnheim, R. (1954). Art and visual perception. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Augustin, M. D., Leder, H., Hutzler, F., & Carbon, C. C. (2008). Style follows content: On the microgenesis of art appreciation. Perception, 128, 127–138.

Bachmann, T., & Vipper, K. (1983). Perceptual rating of paintings from different artistic styles as a function of semantic differential scales and exposure time. Archiv fur Psychologie, 135, 149–161.

Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Biederman, I. (1987). Recognition-by-components: A theory of human image understanding. Psychological Review, 94, 115–147.

Biederman, I., & Cooper, E. E. (1991). Priming contour-deleted images: Evidence for intermediate representations in visual object recognition. Cognitive Psychology, 23, 393–419.

Brodovich, A. (1961). Brodovitch on photography. In C. H. Traub, S. Heller, & A. B. Bell (Eds.), The education of a photographer (pp. 133–139). New York: Allworth Press.

Brown, S., Gao, X., Tisdelle, L., Eickhoff, S. B., & Liotti, M. (2011). Naturalizing aesthetics: Brain areas for aesthetic appraisal across sensory modalities. NeuroImage, 58, 250–258.

Bruce, V., Hanna, E., Dench, N., Healey, P., & Burton, M. (1992). The importance of “mass” in line drawings of faces. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6, 619–628.

Burgin, V. (1977). Looking at photographs. In L. Wells (Ed.), The photography reader (pp. 130–137). New York: Routledge.

Cartier-Bresson, H. (1952). The decisive moment. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Chatterjee, A. (2003). Prospects for a cognitive neuroscience of visual aesthetics. Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts, 4, 55–60.

Crouzet, S. M., Kirchner, H., & Thorpe, S. J. (2010). Fast saccades toward faces: Face detection in just 100 ms. Journal of Vision, 10, 1–17.

Davies, G., Ellis, H., & Shepherd, J. (1978). Face recognition accuracy as a function of mode of representation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 180–187.

Fechner, G. T. (1876). Vorschule der Ästhetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Gombrich, E. H. (1960). Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gombrich, E. H. (1999). The uses of images: Studies in the social function of art and visual communication. London: Phaidon Press.

Graham, D. J., & Redies, C. (2010). Statistical regularities in art: Relations with visual coding and perception. Vision Research, 50, 1503–1509.

Hekkert, P., & van Wieringen, P. C. W. (1996). Beauty in the eye of expert and nonexpert beholders: A study in the appraisal of art. American Journal of Psychology, 109, 389–407.

Kimchi, R., & Peterson, M. A. (2008). Figure-ground segmentation can occur without attention. Psychological Science, 19, 660–668.

Kirchner, H., & Thorpe, S. J. (2006). Ultra-rapid object detection with saccadic eye movements: Visual processing speed revisited. Vision Research, 46, 1762–1776.

Kirsh, A., & Levenson, R. S. (2000). Seeing through paintings: Physical examination in art historical studies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt psychology. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kreitler, H., & Kreitler, S. (1972). Psychology of the arts. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kuchinke, L., Trapp, S., Jacobs, A. M., & Leder, H. (2009). Pupillary responses in art appreciation: Effects of aesthetic emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3, 156–163.

Latto, R., & Harper, B. (2007). The non-realistic nature of photography: Further reasons why Turner was wrong. Leonardo, 40, 243–247.

Latto, R., & Russell-Duff, K. (2002). An oblique effect in the selection of line orientation by twentieth century painters. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 20, 49–60.

Leder, H. (1996). Line drawings of faces reduce configural processing. Perception, 25, 355–366.

Leder, H. (2003). Familiar and fluent! Style-related processing hypotheses in aesthetic appreciation. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 21, 165–175.

Leder, H., Belke, B., Oeberst, A., & Augustin, D. (2004). A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. British Journal of Psychology, 95, 489–508.

Leder, H., & Bruce, V. (2000). When inverted faces are recognized: The role of configural information in face recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53A, 513–536.

London, B., & Upton, J. (1998). Photography. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Marr, D. (1982). Vision. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

McManus, I. C., Zhou, F. A., l’Anson, S., Waterfield, L., Stöver, K., & Cook, R. (2011). The psychometrics of photographic cropping: The influence of colour, meaning, and expertise. Perception, 40, 332–357.

Millis, K. (2001). Making meaning brings pleasure: The influence of titles on aesthetic experiences. Emotion, 1, 320–329.

Oliva, A., & Torralba, A. (2001). Modeling the shape of the scene: A holistic representation of the spatial envelope. International Journal of Computer Vision, 42, 145–175.

Palmer, S. E., Gardner, J. S., & Wickens, T. D. (2008). Aesthetic issues in spatial composition: Effects of position and direction on framing single objects. Spatial Vision, 21, 412–449.

Pelli, D. G. (1999). Close encounters—an artist shows that size affects shape. Science, 285, 844–846.

Phillips, R. J. (1972). Why are faces hard to recognize in photographic negative? Perception & Psychophysics, 12, 425–426.

Ramachandran, V. S., & Hirstein, W. (1999). The science of art: A neurological theory of aesthetic experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6, 15–51.

Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 372–422.

Reber, R., Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 364–382.

Rosenblum, N. (2007). A world history of photography. New York: Abbeville Press.

Rubin, E. (1915/1958). Figure and ground. In D. C. Beardslee & M. Wertheimer (Eds.), Readings in perception (pp. 194–203). Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Russell, P. A. (2003). Effort after meaning and the hedonic value of paintings. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 99–110.

Russell, P. A., & Milne, S. (1997). Meaningfulness and hedonic value of paintings: Effects of titles. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 15, 61–73.

Silvia, P. J. (2005). Emotional responses to art: From collation and arousal to cognition and emotion. Review of General Psychology, 9, 342–357.

Silvia, P. J. (2009). Looking past pleasure: Anger, confusion, disgust, pride, surprise, and other unusual aesthetic emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3, 48–51.

Tinio, P. P. L., & Leder, H. (2009). Natural scenes are indeed preferred, but image quality might have the last word. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3, 52–56.

Tinio, P. P. L., Leder, H., & Strasser, M. (2010). Image quality and the aesthetic judgment of photographs: Contrast, sharpness, and grain teased apart and put together. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5, 165–176.

Tinio, P. P. L., Smith, J. K., & Potts, K. (2010). The object and the mirror: The nature and dynamics of museum tours. International Journal of Creativity and Problem Solving, 20, 37–52.

Torralba, A. (2009). How many pixels make an image? Visual Neuroscience, 26, 123–131.

Yin, R. K. (1969). Looking at upside-down faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 81, 141–145.

Zeki, S. (1999). Inner vision: An exploration of art and the brain. New York: Oxford University Press.