Pre-Islamic Arabia

PUTTING ANY religion’s origins under the microscope is an endeavor fraught with numerous tensions. Are we supposed to believe as true the stories that religious people tell themselves? Or do we attempt to disprove such stories using categories drawn from the secular sciences? The discrepancy between these two approaches symbolizes the tensions inherent to the modern study of religion, representing another variation on the classic theme of the apparent incommensurability between faith and reason. Outsiders usually dismiss religious accounts of origins as “mythic” and of little historical value. Insiders, by contrast, read the exact same stories but regard them as truthful accounts grounded in the historical record.

According to the earliest Muslim accounts—accounts written at least 150 years after the times on which they purport to comment—Islam represents the restoration of an original

monotheism on the Arabian Peninsula. According to this account, this restoration was the result of Muhammad’s fight against

polytheism and forgetfulness: the Arabs are said to have forgotten their original monotheistic impulse and to have begun to worship other gods. The advent of Islam accordingly represents the triumph of universalism over particularism, good over bad, justice over injustice, and so on.

Like all accounts of religious origins, the rise of Islam is predicated on a sharp disjuncture from its immediate environment. This fledgling Islam, like all new religious movements, had to find a balance between a connection to the distant past, on the one hand, and a shattering of the immediate past, on the other. The former disarms the charge of innovation, and the latter shows the uniqueness of the new message. In the case of Islam, connections were made between Arabs and traditional monotheisms of the distant past supplied by Jews and Christians, and the shattering of the immediate past enabled Islam to differ from its immediate polytheistic context.

All of this, however, takes place against a murky backdrop in which memory and desire, fact and fiction, collide. Because all accounts of religious origins are written only after the fact, they are often filtered and imprecise, describing what should have happened instead of what actually did happen. Scholars of religion usually refer to such stories nonjudgmentally as “myths,” or stories that people tell themselves to make sense of their worlds. The end result is that we often lack firm ground from which to perceive origins in any way except imprecisely. We must often take the same texts and narratives that insiders regard as historical and authoritative and subject them to different sorts of analysis.

Religions, like any social formation, do not appear fully formed. It is thus necessary to inquire into the larger contexts out of which religions emerge and against which they subsequently define themselves. As shown in this chapter, those people who formed Islam (whether Muhammad or the final redactors of the Quran or later legists) inherited a larger Near Eastern religious, cultural, and literary vocabulary that they shaped to fit their own needs and an emerging community’s needs. Unfortunately, however, we know very little about what was inherited and what was new. Although this question is certainly of interest to us today, it most likely did not concern seventh- and eighth-century followers of Muhammad. As a result, it is very difficult to illuminate the relationship between the rise of Islam and the existence of various Judaisms, Christianities, and other religious forms that existed within the Red Sea basin just prior to the advent of Islam. The Quran, whose dating is not without its own set of problems, offers very little help in this regard.

A second problem that faces the scholar of Islamic origins is the history of Western polemical writings that deal with this subject. Since the medieval period, European scholars have often defined Islam negatively, making it into little more than a seventh-century invention and corruption of more “stable” monotheisms (such as Judaism and Christianity; note that these names are always put in the singular and rarely, if ever, put in the pluralized forms “Judaisms” and “Christianities”). There exists, in other words, a lengthy history of non-Muslims that speaks about Islamic origins as a way to undermine the religion. The alternative, however, is not necessarily more satisfying because it has the tendency to take later Muslim theological accounts concerning the rise of Islam at face value. These later accounts are subsequently projected back onto the earliest period, even though it is a period about which we have very little evidence, and then assumed to provide accurate historical accounts of the period in question.

1Although archaeological activity certainly takes place within the Red Sea basin, including the Arabian Peninsula, we still know very little about the early rise of and activity in Mecca (entry to which is forbidden to non-Muslims) and Medina, the two epicenters of Islam’s earliest formation. In addition, we possess very few written records that provide us with eyewitness accounts. Some scholars have attempted to use only non-Islamic sources (including inscriptions and coins) to reconstruct the rise of Islam.

2 Despite such attempts, our ability to chart and explain Islamic origins must necessarily be speculative and uncertain.

This chapter has two aims. First, it attempts to provide a historical snapshot of what little we know about pre-Islamic Arabia. What, for instance,

might the Red Sea basin in general and the Arabian Peninsula in particular have looked like socially, culturally, economically, and religiously? The following problem is indicative of the difficulties in creating a snapshot of pre-Islamic Arabia. We certainly know that Jews (or, perhaps more accurately, Jewish–Arab tribes) and Christians (again, more accurately, Christian–Arab tribes) inhabited parts of Arabia; however, we know very little of these groups’ belief structures and religious contours. We should avoid assuming that race and ethnicity (e.g., Jew or Arab) were mutually exclusive cultural markers in the periods before, during, and even immediately after the formative period of Muhammad’s movement. There is also a danger of imposing our own theological differences—for example, among Christian, Jew, pagan, and Muslim—on this period. If we look at all these categories as fluid and unstable, we might get a different appreciation and understanding of the period in which Islam arose.

3Not unlike most chapters in this book, this chapter offers two often contradictory accounts—insider and outsider accounts—that

attempt to describe the emergence of various Islams in Arabia in the seventh century. The insider account tells a narrative of Muhammad’s response to the divine message and his skillful navigation of the Arabian tribes from the bonds of idolatry to the freedom of Islam. Muhammad’s message, embodied in the Quran, was responsible for the rapid spread of Islam throughout the Mediterranean basin and beyond. The outsider or more skeptical approach, by contrast, argues that any account of origins must be based on historical, archaeological, and philological proof. The projection of later Islamic traditions, according to this approach, onto a period wherein we know next to nothing is largely an ideological project of later centuries and of limited historical value.

The final section of this chapter attempts a synthesis of the two accounts, showing how and why later Muslim thinkers projected various values onto the emergence of Islam.

The customary presentation of pre-Islamic Arabia is based on a later Islamic myth of its isolation and separation from the larger empires of the area. This trope of a desert people wandering in darkness and receiving a divine message is certainly a common one in ancient Near Eastern religious cultures. However, if we assume the mythic trope as historical narrative, as is frequently done, we miss out on the active involvement of pre-Islamic Arabs and other tribes in these larger empires. It is certainly clear, for instance, that the peninsula functioned as an important nexus on a number of east–west and north–south trade routes.

4 Pre-Islamic Arabia did interact with the rest of the Middle East and did so increasingly as time progressed. The claim that Arabia was untouched by the major empires of the regions

and their religions is, however, a potentially useful theological claim. The myth of pre-Islamic isolation served a number of functions. First, it allowed Islam to appear miraculously with Muhammad on the world stage. Second, it permitted Islam to emerge untouched by other monotheisms in the area, thereby protecting Islam from later charges that it and its scripture, the Quran, are copies of Jewish and Christian sources. Third, it signals the uniqueness of Muhammad’s message that inspired the tribes of Arabia to take up monotheism. Finally, it contributes to the creation of a foundation narrative to rival the accounts of origins found in other religions, most notably various Judaisms and Christianities, some of whose practitioners undoubtedly formed the core of Muhammad’s early movement.

It is important to be aware that Arabia was not monolithic in terms of its cultural, religious, and material practices. It consisted of distinct geographical regions, each of which was settled by various peoples with their own cultural and religious traditions. Scholars who work in pre-Islamic Arabia tend to divide the region into three cultural regions: East Arabia (comprising modern-day Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, and Oman), South Arabia (roughly corresponding to modern-day Yemen), and North and Central Arabia (modern-day Saudi Arabia minus its eastern coast, the Sinai and Negev deserts, and parts of modern Jordan, Syria, and Iraq).

5 The earliest written sources from East Arabia date to roughly 2500

B.C.E., and those from the other regions to roughly 900

B.C.E. The Arabs made up only one group in this area, but they became the most successful, eventually absorbing all the other groups in the region.

The pre-Islamic Red Sea basin occupied a distinctive geographic location that in many ways functioned as a conduit between civilizations and continents. It witnessed the emergence of several civilizations, the relics of which are still evident today. One such civilization was that of the Nabateans, who created the city of Petra in modern-day Jordan (

figure 1), one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Other such Arabian civilizations prior to the fifth century

C.E. include the Lakhmid kingdom in the North around the Euphrates River and the Himyar kingdom in the Southwest near Yemen.

The Arabian Peninsula existed between three major agricultural centers: Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. Each of these three lands were connected to what one historian calls “political hinterlands.”

6 That is, if one traveled east, north, or south, one would soon come upon some of the major civilizations of late antiquity. In Iraq, for example, there existed the Sassanian Empire; just beyond Syria lay the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire; and in Yemen there existed the Abyssinian Empire. Subsequent Islamic myths of isolation and separation to the contrary, Arabs seem to have been active participants in the various social, economic, cultural, and religious features of these diverse imperial powers.

Virtually all the inhabitants of pre-Islamic Arabia were members of a tribe, a mutual aid group connected to a larger notion of kinship. These tribes were composed of a hierarchy of overlapping loyalties largely determined by the closeness of kinship that ran from the nuclear family to the tribe and even, in principle at least, to the entire ethnic or linguistic group. Disputes were settled, interests pursued, and justice and order maintained by means of this organizational framework. Early inscriptions from South Arabia mention that tribes were also bound together by allegiance to the cult of their patron deity, in relation to whom they were designated “the children,” and by loyalty to their king.

7FIGURE 1 Facade of the Treasury, Petra, Jordan. (Photograph by Bernard Gagnon; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

These tribes possessed a strict code of honor that was based on

diyafa (hospitality), which required that even one’s enemy must be given shelter and fed for some days. Generosity was a related virtue, and even today in many Bedouin societies gifts must be offered and cannot be declined. The community was also responsible for taking care of the poor in its midst, and in many of the tribes tithing (a form of tax) was mandatory.

Hamasa (courage, bravery) was also closely linked to Bedouin honor, indicating the willingness to defend one’s tribe for the purpose of tribal solidarity and heavily bound up with the concept of

muruwwa (manliness). Although such features may well be pre-Islamic, it is worth noting that they might also be a part of the backward projection of later Muslim virtues onto the distant past.

The integration of tribes was largely dependent on time, place, and wealth. The wealthier tribes, for example, had a network of clan chiefs and even a paramount (or head) chief who could coordinate tribal members for collective action. Proximity to and trade with the larger powers in the region further increased these paramount chiefs’ power and prestige because larger powers often chose to work with them individually. Especially in the rich agricultural-based regions of South Arabia, fairly elaborate kingdoms arose, whereas poorer camel-herding nomadic tribes in the inner deserts tended to consist of little more than loose assemblages of local groups.

8Various tribes and tribal configurations existed throughout the peninsula and, depending on the time in question, were tributaries to larger groups located outside Arabia. It was not uncommon for many of these tribes to form various alliances with one another in the pursuit of common causes. There also existed several important towns throughout Arabia. For example, numerous pre-Islamic towns have been located and excavated in the modern kingdom of Saudi Arabia. These towns—for example, Qaryat al-Faw and Madain Saleh—were on important north–south trade routes linking the peninsula to the great economic and cultural centers of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Egypt. Pastoralists who subsequently became involved in trade largely settled these towns; archaeological evidence also links these towns to larger kingdoms in the area (e.g., Nabatea). There is also evidence that such towns were highly literate and had large marketplaces and religious shrines.

The existence of such towns is significant because they reveal that Arabia, although largely desert, most certainly was not an isolated oasis. The Arabian Peninsula played an important role in trade; it was on the radar of the region’s larger empires; and, most important for

chapter 2, it had connections to other regional monotheisms.

Interactions certainly occurred between these towns and the region’s larger empires. These empires tended to manipulate the tribes, which increasingly became sedentary in settlements or caravan towns. As the larger powers declined in the late antique period, such towns and the region’s nomadic tribes began to reconfigure. Moreover, given the tribal nature of Arabian society, it was not uncommon for various intertribal feuds to emerge, most likely on account of relationships to the larger trade routes that intersected Arabia. This network of trade, feuds, and political struggles tended to “involve the whole of Arabia in a single political complex, if a rather incoherent one.”

9The Red Sea basin was closely linked to both the Mediterranean and Mesopotamian worlds. As in those worlds, the major form of religious expression in the basin was polytheism, the belief in many gods and goddesses.

10 We know many of the names of the Arabs’ tribal deities because the most common aim of inscriptions was to invoke them, praise them, or give thanks to them. Yet, as Robert Hoyland, a specialist in pre-Islamic Arabia, remarks, “Names do not tell us much, and the brevity of most of these texts makes it difficult for us to understand the nature and function of the gods or to comprehend what they meant to their worshippers.”

11 Based on surviving inscriptions, it has been deduced that the main god was Athtar, who seems to have been related to the Ishtar cult in the northern part of Arabia. The cult of Athtar also appears to have been widespread throughout the region, albeit with various manifestations, as attested by inscriptions in various local shrines. One inscription has an individual thanking another god for “interceding on his behalf with Athtar.”

12If Athtar was a remote deity, many other gods and goddesses were of significance to particular tribes. The popularity of these gods and goddesses seems to have been determined by both the tribe and the particular period in question.

13 From the Quran (e.g., 71:23), we are able to glean the existence of a number of others gods and goddesses, including al-Qaum (the god of war and of night), Wadd (the god of love and friendship), Nasr (the god of time), and Nuha (the sun goddess). Based on inscriptions from South Arabia, we also know that some of these gods functioned as patron deities to particular tribes: Wadd, for example, was the patron of the Mineans, Amm of the Qatabanians, and Sayin of the Hadramites.

In addition to naming deities, inscriptions also tell us of anonymous guardian spirits (

mndht). They apparently offered protection to encampments, families, and individuals. Inscriptions from North Arabia speak of

ginnaye, possibly related to the

jinn mentioned in the Quran. Mention is also made of various malevolent beings and spirits.

14In the fourth century

C.E., a number of South Arabian inscriptions increasingly began to speak of a monotheistic cult of the deity Rahmanan—the “Merciful One,” “the Lord of heaven and earth.” Scholars are unsure if this high god is related to the earlier polytheistic structure or a new development, perhaps connected to the increased prestige or importance of Jewish–Arab and Christian–Arab tribes within the peninsula. It is also difficult to determine whether Rahmanan is related to

Allah, which in Arabic quite literally means “the God,”

15 or, perhaps more familiarly, “God.” There is evidence that pre-Islamic Arabs believed in Allah as the high god in the pantheon who gave birth to three goddesses: Al-lat (the Goddess), Manat, and al-Uzza (see, for example, Quran 53:19–23), although no mention is made of a consort. According to some Nabatean inscriptions, however, Al-lat is identified as the consort of Allah.

The supreme cultural expression of Arabian tribal life, whether nomadic or town dwelling, was a highly cultivated body of poetic expression, which in subsequent generations would be referred to as “classical” Arabic. This poetry was highly stylized in terms of its themes, meter, and prosody, and its creators were often tribal spokespersons who received great patronage. Professional reciters recited new poems throughout the peninsula. In Mecca, which will play an important role in the formation of Muhammad’s message, there seems to have been an annual poetry competition connected to pre-Islamic religious customs and rituals.

16 It was from this highly literary and poetic environment that the Quran emerged and against which it ultimately had to compete for listeners (see

chapter 3).

By the mid-sixth century

B.C.E., there existed at least three major settlements in northern Arabia, along the southwestern coast that borders the Red Sea. The settlements in this area, known as the Hijaz, grew up around oases, or isolated areas of vegetation connected to a spring. In the center of the Hijaz was Yathrib, later renamed Medina. Around 250 miles (400 kilometers) south of Yathrib was the mountain city of Taif, northwest of which lay Mecca. Although the area around Mecca was completely barren, Mecca was the wealthiest of the three settlements, receiving abundant water via the Zamzam Well and occupying a position at the crossroads of a major caravan route.

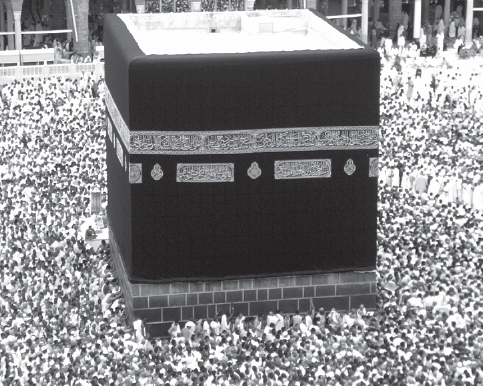

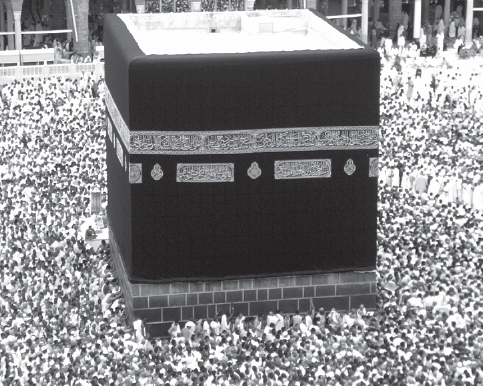

Even before the rise of Islam, Mecca was an important economic and religious center in the Arabian Peninsula. According to later Muslim tradition, the

Kaʿba, or “Cube,” was originally created by Ibrahim (Abraham) on one of his visits to his son Ismail (Ishmael)—his son by the maidservant Hagar, who, in the Bible’s mythic presentation, was subsequently ordered to leave his house after his wife, Sarah, gave birth to Isaac (

figure 2). The Islamic tradition, however, remembers Hagar as one of the wives of Abraham. The ground on which the Ka

ʿba was built, according to Islamic memory, had previously been hallowed by Adam, the first man. It subsequently became a polytheistic shrine when later Arabs forgot its true purpose and began to set up idols to their tribal deities within.

This story interestingly presents Muhammad’s message, something that was largely created and spread among town dwellers, as a nomadic story. This presentation may well be the result of the fact that later townsmen were, as Hoyland puts it, “strong on religion, but short on identity.”

17 As the followers of Muhammad entered regions with lengthy and venerable religious traditions, they needed their own religious history and identity. They seem to have picked up on the idea—around at least since the time of the Jewish historian Josephus (ca. 37–100

C.E.)—that the Arabs were descendents of Ishmael. This idea enabled the early Muslims to fashion a religious pedigree for themselves. In terms of identity, these early Muslims turned to the nomadic Arabs, “who were short on religion, but strong on identity.”

Because it is impossible to prove whether the biblical patriarchs actually existed, let alone visited Mecca and environs, it becomes necessary to look for other possible contexts regarding the origins of the Ka

ʿba. This task unfortunately proves to be difficult. Several informed guesses are possible. One is that this mythic story was undoubtedly facilitated by a shared cultural history that included a number of themes and motifs found, with different emphases and stresses, in cognate literatures such as the Hebrew Bible or the epic of Gilgamesh (an epic poem dating roughly to the seventh century

B.C.E. from Mesopotamia). Related to this shared cultural history is the notion that the patriarchal origins of the shrine could well have provided subsequent generations of Arabs seeking to legitimate their religion with a monotheistic birthright and pedigree. In addition, earlier Greek and Roman authors speak of a fairly widespread cult of stones—both unshaped and carved into various idols—among Arab tribes. Even later Muslim authors comment on this cult and trace it back to the subsequent degeneracy of the tribes descended from Ismail. In its earliest incarnation, the Ka

ʿba might well have been connected to this type of worship. Early Muslim sources also mention the fact that there were several shrines, several Ka

ʿbas, round Mecca, which would have made the region and not just the city a religious center.

FIGURE 2 The Kaʿba, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. (Photograph by al-Fassam; courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

We can probably assume that historically Meccans, as a settled population, created and venerated gods at fixed shrines. Less transitory Bedouin probably carried their gods with them. The objects they venerated seem to have been stones, other animate and inanimate objects, and the sky—all of which were worshipped most likely because the gods were thought to reside in them.

18 These sacred stones and idols increasingly became fashioned as human likenesses, and by the time just prior to Muhammad they seem to have taken on distinctive names and perhaps even personalities.

19The harsh conditions of the Arabian Peninsula indicated a scarcity of resources, which meant a near-constant state of tension between the various tribes. Once a year, however, these tribes would declare a truce and converge on Mecca in an annual pilgrimage, or

hajj. This pilgrimage, like the one that would later be resignified by Islam, was intended for religious reasons, to pay homage to the Ka

ʿba, wherein the tribes housed the idols of their deities, and to drink from the Zamzam Well. Poetry, an important part of Bedouin culture, was recited in competitions.

20 Moreover, this pan-tribal pilgrimage witnessed the arbitration of disputes, the resolution of debts, and the celebration of trade at various fairs. This annual event gave the tribes a sense of identity beyond the tribal unit and established Mecca as an important focus of the peninsula.

Given both the importance of the trade routes to Arabia and the fact that larger geopolitical forces surrounded Arabia, it is certainly unlikely, as previously noted, that the peninsula existed in a religious vacuum or was untouched by the existence of other imperial powers and their monotheisms. Not only were all the political hinterlands connected to monotheistic civilizations, but there is evidence of the existence of Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians (followers of a monotheistic religion based on the teachings of Zoroaster, who lived in Persia in the sixth century

B.C.E.) in Arabia well before the time of Muhammad. More important than asking whether other monotheisms existed in the area, the more accurate and pressing questions are: What were the contours and contents of these monotheisms? And, given the fluid ethnic and religious contexts of sixth- and seventh-century Arabia, is it even possible to assume that these monotheisms represent distinct markers of identity and difference for their adherents?

JUDAISMS

If we accept the historicity of the Arab sources on the existence of Jews in the Arabian Peninsula,

21 Jewish tribes arrived in the Hijaz in the aftermath of the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70

C.E. There is also clear evidence that by the end of the fourth century there existed a Jewish presence, which seems to have arrived there from Yemen. We also know that in the mid-fifth century

C.E. one of the Yemeni kings adopted some form of Judaism as the official state religion. The significant presence of Judaism in Yemen lasted for centuries—long after it ceased to be the state cult. There was also an important Jewish community in Elephantine (on the Nile, part of the Red Sea basin), not to mention Jews in Alexandria. All these Jewish communities apparently had historical and political ties to Iran.

The Jews of Arabia were an integral part of this scene. The Constitution of Medina—a text attributed to Muhammad when he established a polity in Medina/Yathrib—names no less than seven Arab tribes of Jews, and there are other passing references to a house of study (

bayt al-midrash) there.

22 Moreover, Muhammad Ibn Ishaq—one of Muhammad’s later biographers, whom we meet in

chapter 2—links the Jewish community of Yathrib to the Yemeni Jews, suggesting that both trade networks and cultural networks ran the length of the Red Sea basin and reached not only into Mesopotamia, but also to the Iranian plateau.

The existence of these Jewish tribes in Arabia apparently predate the codification of the Babylonian Talmud, one of the main documents of rabbinic Judaism, around 500

C.E. Although this codification occurred in the rabbinical academies of Babylonia, which were in relative close proximity to the area, it is unclear how much jurisdiction such academies would have had among Jews in the Red Sea basin. At the same time, however, it is important not to assume an orthodoxy of fixed and ascertainable Jewish identity and practice based on the rabbinic academies of Babylonia and then use this orthodoxy as the standard against which to judge the “authenticity” of Arabian Jewishness. The Talmud, as a product of late antiquity, further reveals the fluid and evolving nature of Judaism in this period.

23

PRE-ISLAMIC ARABIAN MONOTHEISMS?

THE CASE OF THE HUNAFA

An overwhelming majority of scholars working on early Islam claims that the main impetus toward monotheism likely came from the existence of various Judaisms and Jewish–Arab tribes in the Hijaz, especially in Yathrib. However, early Islamic sources, including the Quran, make reference to another group of individuals referred to as

hunafa (sing.,

hanif). These individuals—interestingly, never defined as a community—professed a monotheism that was neither Jewish nor Christian but was somehow regarded as loosely connected to the figure of Abraham.

It seems most likely, however, that this designation is not historical, but religious. With respect to the latter, it served several important functions. First, it provided a spiritual category in which to locate Muhammad. Making him into a hanif, neither Christian nor Jew—which would obviously taint his message—solved the equally unpalatable issue of his being a polytheist. Second, it contributed to Muhammad’s mission as being the restoration of a primitive monotheistic cult that the Arabs of his day had largely forgotten.

CHRISTIANITIES

The same kinds of questions arise for the existence of Christianities in the Red Sea basin. If the period just before the rise of Muhammad was one in which rabbinic Judaism was being formulated in Babylonian academies, it was also a period in which the Catholic Church was defining itself and working out what would become “orthodox” belief and doctrine by weeding out what would subsequently become labeled “heretical” movements. Interestingly, all the main forms of Christianity in Arabia were forms of the religion that the church in western Europe deemed more heterodox.

24Monophysite Christianity appears to have been one of the more dominant strains of Christianity in the area. Monophysitism adopted the christological position that Jesus has only one nature (mono = one, phusis = nature), as opposed to the orthodox position adopted at the Council of Chalcedon (451 C.E.) that Jesus possesses two natures, one divine and one human. The other major form of Christianity in the area is Nestorianism, which holds that Jesus existed as two separate persons, the man Jesus and the divine Son of God, or Logos, rather than as a unified person.

The existence of Christian Arabs at the time before Muhammad raises all sorts of interesting questions regarding identity. What, for example, did it mean to be a Christian Arab at this time? Although these tribes may have identified with and even allied with larger Christian empires in the region, the heterodox and even heretical teachings that dominated in Arabia would certainly have limited such identification. Or, again, as we saw in the possible existence of Judaisms in the area, perhaps some form of Arab Christianity—along with other forms of (Arab) Judaism and (Arab) Zoroastrianism, in addition to other local cults—represented the fluidity of loyalties and practices out of which Muhammad’s social movement emerged.

25 And, perhaps unlike those religious traditions (such as rabbinic Judaism or normative Christianity) who sought to impose on the tribes the orthodoxies, orthopraxies, and exclusive loyalties to one community or another, Muhammad’s movement succeeded because in its formative stages it both appealed to and encouraged a variety of beliefs and practices.

26IRANIAN RELIGIONS

Iranian religions were also present in the peninsula. Zoroastrianisms—traditionally the national religion of Iran and the belief that good and evil come from distinct sources—seems to have been present in the area on account of a Sassanian military presence along the Persian Gulf and in South Arabia and on account of trade routes between the Hijaz and Iraq. It also seems that some Arabs converted to Zoroastrianism in the northeastern part of the peninsula. Several Zoroastrian temples were apparently constructed in Najd—whether Iranian colonists or Arab Zoroastrians were responsible for this building activity is unclear.

There is also some evidence for the existence of Manicheans in Arabia. Having its origins in the third century

C.E., Manicheanism is also an Iranian religion that seems to have been heavily influenced by Gnosticism. Its cosmology documents the struggle between a good, spiritual world of light and an evil, material world of darkness. Several early sources indicate the presence of people professing

zandaqa—that is, Manicheanism—in Mecca. Although this term is a loan word from Middle Persian, it later took on the connotation of “heretic.” There also exist several Persian loanwords in the Quran—most notably

firdaws (paradise)—that may well show the influence of Iranian religious thought on the Arabs at the time of Muhammad.

According to accounts in later Muslim sources—which include the Quran; the hadith (sayings of Muhammad); the biography of Muhammad;

tafsir (commentary), especially on the Quran; and other genres—the original religion of the Arabian Peninsula, indeed, the original religion of all humanity, was that of

islam. The word

islam means “to surrender”—that is, surrender to the will of God. The adjective

muslim, deriving from the same root, means “one who surrenders.” Arabic, like all Semitic languages, lacks capital letters, so one can theoretically and ostensibly submit to the will of God without being a capital M “Muslim.” On this reading, although Muhammad or those who came after him brought capital I “Islam” to the Arabian tribes,

islam has always existed—in some way, shape, or form—in the world. According to this model, everyone from Adam, the first man, to Ibrahim (Abraham), Musa (Moses), Dawud (David), Isa (Jesus), most of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible, and others were

muslims. According to the Quran 3:67, for instance, Abraham is described in the following terms:

“Abraham was not a Jew [

yahudi] nor was he a Christian [

nasrani]; he submitted his will to God [

muslim] and he did not add gods to God.”

The later Islamic tradition interpreted such passages to mean that even though Ibrahim may not have been a Muslim and did not practice Islam in the same way Muslims would after Muhammad, he—like all individuals who submitted his will to God—was nonetheless still a muslim.

Related to this is the concept of

fitra, or one’s innate submitting nature. According to Muslim tradition, all humans are born with a

fitra, and it is what predisposes them toward

islam. As this concept developed, it came to be understood that every human is born a

muslim and only subsequently “judaized,” “christianized,” “hinduized,” or something else by one’s parents.

Perhaps because Muhammad’s message spread so quickly in the years after his death, it immediately entered a large marketplace of religions that could claim much older pedigrees. Religions and religious practitioners tend to put pride of place on antiquity, so the concept of fitra could be employed to argue that Islam, rather than being the newest of religions, was in fact the most ancient—the true religion of the Hebrew prophets, Moses and Jesus.

The question now arises: If, according to the Islamic tradition, Islam is the original religion of humanity, why were many of the Arabian tribes polytheist? How, in other words, did Arabia largely become polytheist and idolatrous? The answer developed by Muslim theologians of the eighth century and beyond is that through time the tribes of Arabia subsequently forgot their original submitting natures and gradually began to worship idols and other deities. It would be up to one individual, an Arabic prophet, to restore the Arabs to their original

fitra. This Arabic prophet, encountered in greater detail in

chapter 2, was Muhammad. Later portrayed as an illiterate prophet, Muhammad was someone unschooled in these prior monotheisms, not tempted by traditional monotheisms, but who, like Abraham, left the religion of his forefathers in order to carve out new religious space for himself and for his followers.

The religion of pre-Islamic Arabia was monotheistic in the ancient past, but it gradually gave way to a period of chaos, which, again, the later theologians sharply constructed so as to juxtapose it against the newness of Muhammad’s message. The time immediately preceding the advent of Muhammad was known as the

jahiliyya (period of ignorance). Despite the fact that later Muslim sources claim a watertight border between the

jahiliyya and Islam, that border was most likely anything but.

27 Borders, given their very nature, admit of porosity and therefore need to be policed. The unstated goal behind the construction of this border between

jahiliyya and Islam seems to have been to create a genuine Muslim myth that could be configured in a way that was diametrically opposed to the ideals and imagination of pre-Islamic Arabia. For example, whereas the

jahiliyya had poetry, Islam has the Quran; whereas the

jahiliyya had idolatry and mythology, Islam possesses pure monotheism; whereas those living in the

jahiliyya practiced female infanticide, Islam recognizes the positive role of women; and so on. The border between them, like all borders imposed retroactively, is more apparent than real. In fact, the presence of the

jahiliyya clarifies that which Islam must be seen both as abrogating and as fulfilling. Without the

jahiliyya, there could not be Islam. The goal should not necessarily be to show how the latter is distinct from the former, but how the former permeates and influences the latter.

In the introduction, mention was made of the “authenticity debate” and, in particular, of how to treat the sources that deal with the formation of Islam. A skeptical approach to these sources regards them as historically very problematic and as the attempts by later generations of Muslims to justify and legitimate their vision of what Islam should be. Such an approach questions all the “facts” recounted in this chapter. The result is a very different account of the emergence of Islam. This section provides an overview of some of these theories as a way to show the diversity of opinions and research on these sources.

The previous section recounted the basic account of Islam’s rise that Muslim sources tell and that many Muslims take as true. This story represents the gradual movement from idolatry to monotheism, from forgetting to memory, from islam to jahiliyya to Islam. It is, however, a religious account and, like all religious accounts, should not necessarily be taken at face value. Like the myths of Moses’s receiving the commandments on Sinai and the death and resurrection of Jesus, this account is how Muslims explain their faith. From the perspective of an outsider, however, it is nothing more (or less) than religious stories that do not accurately reflect the mundane record because those who wrote them did not necessarily claim to be creating such a record. Although speculative, the theories regarding the rise of Islam presented here nonetheless help us to think about it using different paradigms and other theoretical models.

Patricia Crone, for example, argues that it has always been assumed that Mecca at the time of Muhammad was the center of a far-flung international trading empire. She questions this assumption, arguing that the state of our knowledge about Meccan trade is so vague and the information provided by the sources so contradictory that any attempt at reconstruction is impossible. She further questions the assumption that Mecca lay close to the Incense Road, which she argues had largely shifted to the sea from overland routes. Moreover, the fact that Mecca is not mentioned in any non-Islamic sources leads her to conclude that it was not the center that later sources claimed it to be. Based on an analysis of sources and trade routes, she concludes that Mecca did not exist in its present location in southwestern Arabia, but in the Northwest. The implication of this theory is that it calls into question the entire narrative edifice on which scholars have constructed Islam.

28The late John Wansbrough has also argued—based on a survey of early Islamic manuscripts, including the Jewish and Christian imagery in the Quran—that the rise of Islam represented a version of a Judeo-Christian sect trying to spread in Arabia. As time evolved, he argues, Judeo-Christian scriptures (i.e., the Hebrew and Christian Bibles) were adapted to an Arab perspective and eventually mutated into what became known as the “Quran,” a pastiche of sources cobbled together from various Arab tribes. Wansbrough argues even more extremely that the traditional history of Islam was ultimately a fabrication by later Muslims who desired to create a religious identity for themselves—presumably an identity independent of Judaism and Christianity. Within this context, he regards Muhammad as a literary trope or a literary creation to provide the Arab tribes with their own Arab version of the Judeo-Christian prophets.

29In another theoretical take on Islamic origins, Patricia Crone and Michael Cook disregard all Muslim sources as later projections and instead focus solely on what they consider to be more reliable non-Muslim historical, archaeological, and philological evidence. According to them, the followers of Muhammad—who claimed descent from Abraham through Hagar—emerged as a heretical branch of Jews intent on retaking Jerusalem from the Byzantine Empire. Fearing assimilation into normative Judaism, this group, which the authors call “Hagarenes,”

30 eventually decided to create their own religion. Driven by the need for an independent theological identity, the Hagarenes created a version of Abrahamic monotheism that included various elements of Judaism, Samaritanism (an early offshoot of Judaism), and Christianity and that eventually crystallized in the late eighth century as Islam. Like Judaism, this new religion possessed a scripture (the Quran as opposed to the Torah), a prophet (Muhammad as opposed to Moses), and a holy city next to a holy mountain (Mecca as opposed to Jerusalem).

One of the most extreme accounts of the origins of Islam presented in recent years may be found in the treatment by the Israeli archaeologists Yehuda Nevo and Judith Koren, who argue that there seems to be little archaeological, epigraphical, and historiographical evidence that Islam existed before the late eighth century (two hundred years later than is customarily presented as the time when Islam emerged). Based on such evidence, they claim that traditional narratives of Islam’s emergence are later constructs that neither can be historically confirmed nor stand up to rigorous historical examination.

31 They further argue that the Arabs were pagan when they assumed power in the seventh century in the regions formerly ruled by the Byzantine Empire and that they created a simple monotheism based on the forms of Judaism and Christianity that they encountered in their newly occupied territories and only gradually developed that monotheism into an Arab religion, which culminated in Islam in the mid-eighth century.

Once again, these theories represent some of the more extreme accounts that attempt to provide a theoretical paradigm for the rise of Islam. Many other scholars or practitioners of the faith have criticized such theories as either ludicrous or hostile to Muslims. The evidence these scholars present is certainly not without its problems, and, as we have seen time and again, they must face the same lack of sources that all who deal with these issues encounter. Yet a theory that proposes the creativity and the task of inventing a cultural and religious identity in the face of rival monotheisms should not strike us as completely farfetched.

It is worth reiterating that we know very little about the origins of Islam. We have neither eyewitness accounts nor, as yet, holistic archaeological data. Most of what we do know does not emerge until the late eighth and early ninth centuries—roughly 150 to 200 years after the death of Muhammad—when Islamic records begin to appear. These records are interested in understanding Islam and in constructing an “orthodox” Islamic identity. They are, as such, what we would largely label as theological or insider accounts. So although they may tell us a great deal about the ways that Muslims represented the origins of their movement to themselves, they tell us precious little about what may actually have happened. This confusion between the representation of Islam’s origin and the reality of that origin, of course, is no different from the confusion regarding the origins of any religious or sectarian movement. Accounts of Islamic origins, like the accounts of religious origins more generally, are largely projections by later groups attempting to read their own agendas into or onto the earliest period with an eye toward legitimation.

As a result, pre-Islamic Arabia up until the second Muslim century is a blank canvas on which later historians and theologians sketch various projections. They all, however, are precisely that: projections that at best can only imagine what happened.

In the final analysis, at least until a major manuscript or archaeological discovery appears, the most pressing question we can try to articulate and then answer is: How and why did early Muslims come to write their own history? It would seem that the Islamic historical tradition arose as a response to a variety of challenges facing the Islamic community during the first several centuries of its existence (eighth to tenth centuries

C.E.). The narratives that they produced—biographies of Muhammad, the sayings of Muhammad, and so on—focused on certain themes of Islamic origins that they undoubtedly selected to legitimize particular aspects of the Islamic community and faith. These themes included the status of Muhammad as a prophet, the affirmation that the community to which they belonged was the direct descendant of the original community founded by the Prophet, Muslim hegemony over vast populations of non-Muslims in the rapidly growing Islamic Empire, and the articulation of different positions in the ongoing debate over political and religious leadership within the Islamic community itself.

But these developments came later. What we must be aware of at this point—what this chapter has tried to present—is the fluidity of identities, religions, and categories in the period immediately before and during the time of Muhammad. The populations of the Red Sea basin seem to have engaged in a variety of religious practices that we now associate with Christianities, Judaisms, Zoroastrianisms, and other local cults. Muhammad’s religious movement apparently emerged from these overlapping and not necessarily mutually exclusive beliefs, loyalties, and practices. As long as Muhammad’s movement conformed to a vague notion of monotheism, its inclusiveness achieved success.

NOTES

This chapter owes much to Peter Wright of Colorado College, who gave an earlier version of it a very judicious and careful reading. Although I acknowledge his comments in various notes, I also thank him here for his very helpful remarks.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

Berkey, Jonathan. The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Crone, Patricia. Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Crone, Patricia and Michael Cook. Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Donner, Fred. Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010.

———. Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing. Princeton, N.J.: Darwin Press, 1998.

Hawting, Gerald R. The Idea of Idolatry and the Rise of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Hodgson, Marshall G. S. The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Vol. 1, The Classical Age of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Hoyland, Robert G. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. London: Routledge, 2001.

———. Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton, N.J.: Darwin Press, 1997.

Insoll, Timothy. The Archaeology of Islam. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

Lecker, Michael. Muslims, Jews, and Pagans: Studies on Early Islamic Medina. Leiden: Brill, 1995.

Lewis, Bernard. The Jews of Islam. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Neuwirth, Angelika, Nicolai Sinai, and Michael Marx, eds.

The Qurān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations in the Quranic Milieu. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Nevo, Yehuda D., and Judith Koren. Crossroads to Islam: The Origins of the Arab Religion and the Arab State. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus, 2003.

Newby, Gordon D. A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1988.

Peters, F. E., ed. The Arabs and Arabia on the Eve of Islam. Aldershot, Eng.: Variorum, 1999.

———. Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Shoemaker, Stephen J. The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Stetkevych, Jaroslav. The Zephyrs of Najd: The Poetics of Nostalgia in the Classical Arabic Nasib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Wansbrough, John E. The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.