Learning to Fly

Becoming a pilot was difficult and dangerous. When Richard enlisted in the Army Air Force as a flying cadet in May of 1941, he knew the odds were against his ever getting flyer’s wings. More than half of the men wishing to be pilots “washed out” or failed the checkup and written tests required to start the program. To be a pilot, you even had to have perfect eyesight! Most who failed were sent to the infantry, where they would fight from the ground. But Richard passed all of the tests with flying colors.

Even so, learning to fly was dangerous. Many who passed the tests were hurt or killed in training accidents or failed to master one of the many skills required to fly. The program required at least 200 hours of flying to become an official pilot. That meant many days and nights of takeoffs and landings, navigation practice, night flying, and other difficult tasks. Just one mistake meant being kicked out of the program, or worse: injury or death. For this dangerous work, cadets were paid only $2.50 a day plus a free room, food, and basic supplies.

Richard’s first stop for flight training was in Tulare (too lair ee), California. This meant his first trip across country, more than 1,500 miles from home. As Richard got on the bus for his long trip, his father gave him some simple advice: “Do as you are told, do your best, and you will do fine.” Richard would remember these words as he traveled around the world to defend his country and follow his dreams.

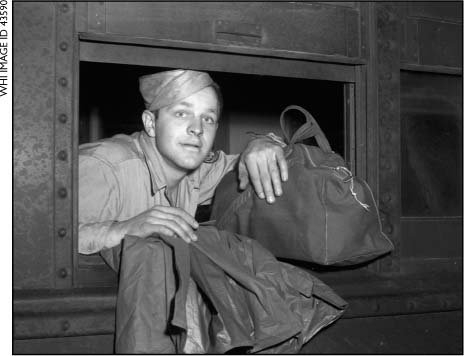

Trains carried soldiers like this one to military bases all over the United States.

The trip from Wisconsin to California was a long and eventful one. His first stop was in Chicago, where he switched from the bus to a train that carried him west. Richard was amazed by the large crowds and constant din of Chicago. “It is so noisy you can hardly hear yourself think,” he said of the city. He liked Chicago better after dark, especially because “at night the town is actually brighter than in daytime.”

Richard was less impressed with the crowded train and its tiny beds. Two cadets squeezed onto each bunk. That meant they had to stay close together, or, as Richard remembered, “the one on the outside wall will fall into the aisle.” The cadets sat for many hours watching the countryside roll by and trading stories about their hometowns. All of them were glad to finally get off the train and start their training.

Richard and his new friends quickly learned that life was tough for first-year cadets. New cadets were called “dodos” and were expected to follow all the orders given by upperclassmen. When an upperclassman called out “Red light!” all the dodos had to freeze until they heard “Green light!”

Training planes like the AT-11 were easier to fly than combat planes.

Dodos were also given demerits for breaking rules. Upperclassmen gave demerits any time a dodo broke a rule. If their uniforms were not perfectly ironed, if they were late to morning exercises, or even if they forgot an important word about flying, they were given a demerit. Six or more demerits, and dodos could not go to town for a night off on the weekend. Every demerit over 8 meant an hour of walking around the military base. One cadet got 20 demerits and was forced to walk around the base for 12 hours straight!

Nearly every minute of a cadet’s life was spent doing some kind of training. Cadets awoke at 5:30, dressed and cleaned their rooms, and then reported for morning exercises at exactly 6:20. They had only 5 minutes to change out of their exercise clothes, wash and comb their hair, and get to the mess hall for breakfast. They marched into the dining hall and then sat silently until the officer commanded them to turn over their plates and eat. The rest of the day was completely filled with classes, athletic drills, and flying practice. When they weren’t learning something, the cadets were marching in straight lines around the base. When lights went out at 10:00p.m., Richard and his classmates were often too exhausted to talk.

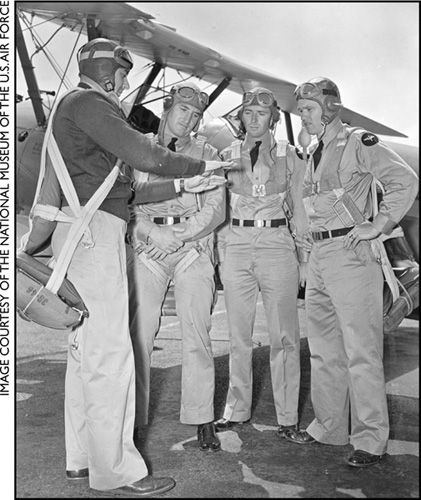

Army Air Force cadets trained long and hard to prepare for war.

Although marching in the 100-degree California sun was rough, academic classes were often the most tiring part of a cadet’s day. In order to use an airplane’s instruments and learn the basics of flight, cadets had to first master algebra and trigonometry. They also learned how to use a slide rule, how airplane engines worked, and how the weather affected an airplane’s flight. Some cadets who were in great physical shape washed out of the flight program because they could not handle these difficult classes.

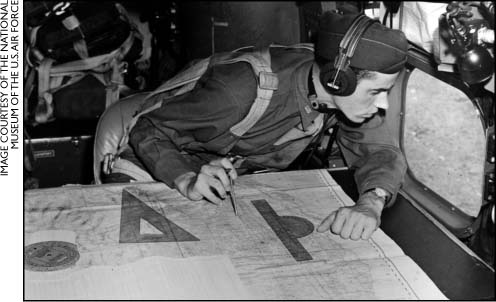

This cadet uses detailed maps to plot a course through unfamiliar skies.

Flying planes for the Army Air Force was challenging work, but also lots of fun.

Luckily, not everything about flight training was difficult. Richard quickly made good friends with many of his fellow cadets. They bragged about their mothers’ home cooking and laughed about the crazy things they were required to do, like being forced to wear goggles when eating grapefruit to protect their eyes from spraying juice. Richard saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time and marveled at the sunny weather that seemed to exist all year long in California.

Best of all, flying was even more fun than Richard had imagined. He loved pushing his airplane through all kinds of acrobatic maneuvers. By turning the control wheel sharply to the left or right, Richard could turn the plane upside down and then roll it back upright again. By pulling back on the wheel he could bring the plane’s nose high into the air until it looped over backward. If he was high enough, he could push the wheel forward and the plane would dive quickly toward the ground.

All of these maneuvers were challenging to perform correctly. Even so, Richard complained that it was too easy. He said he was “so used to steep turns and upside down flying that I don’t get a thrill out of it anymore.” He also had to get used to “blacking out” while flying, a common event for fighter pilots. He later recalled, “I’ve blacked myself out a couple of times diving out of a half roll. The reason is that I roll the plane over on its back and hang there for a minute or more and the blood rushes to my head. Then I dive the plane and come right side up and the pressure causes me to black out. Everything turns black and I can’t see a thing for a few seconds.”

Despite the excitement of learning to fly, Richard often felt homesick. He wrote his mother nearly every day, giving updates on his training and asking about life on the Bong family farm. He also sent his parents money when he could. He knew how badly his help was missed on the farm.

In August of 1941, Richard and the other cadets completed the first stage of flight training. At graduation, their instructor Tex Rankin put on an air show to celebrate, running his plane through dozens of aerial maneuvers. He even wrote the numbers “1941” in the sky!

But that was just the first part of training. The cadets were soon at their next training station, Gardner Field in Taft, California. No longer dodos, the cadets didn’t have to fear the constant badgering of upperclassmen or worry about losing their weekend passes because of too many demerits. What they did do was fly—a lot. Their new training plane was called the Basic Trainer 13-A, a solidly built, slow plane made for simple flying. Cadets were expected to know this airplane inside and out and to master flying it in all sorts of weather.

One of the most difficult tasks to master at Gardner Field was flying at night. Cadets learned to fly using only their instruments, because they could not see landmarks such as rivers or mountains to tell where they were. Richard quickly mastered the skills involved, although night flying made him nervous. “You get a funny feeling when you’re sitting in that airplane and you can’t see the ground,” he said. “It seems like I’m turning to the right when I’m going straight ahead.”

Four F4U Corsairs fly in tight formation over the Pacific Ocean.

Cadets formed close friendships during their many hours together.

Cadets also learned to fly in formation with just a few feet between each airplane. Often 8 or 10 planes flew together in tight “V” patterns, like a flock of geese. This was a common method used to keep airplanes together during combat missions. If one pilot made a small mistake and bumped into his neighbor’s wing, both airplanes could spin out of control and crash. Pilots had to remain focused at all times and constantly check to see where the other planes were around them.

Richard learned the importance of staying alert after surviving an accident at the end of a training flight. As his plane landed he did not slow down fast enough, and he clipped the wing of an airplane stopped at the end of the runway. Richard’s plane tilted violently to one side and spun off of the runway into a ditch. The propeller dug noisily into the ground, and one of the wings was badly damaged. Fortunately, no one was hurt. Richard’s trainers did not consider his mistake serious enough to kick him out of the program—but it certainly was a wake-up call for him!

Learning to fly was often quite stressful. Richard and his fellow cadets escaped the stress by enjoying the sights of California. Richard was not very impressed with the Pacific Ocean, however. “I saw the ocean but it isn’t very inspiring,” he wrote his mother. “It looks like Lake Superior.” He was more excited about a football game he saw between the University of Southern California and the University of Wisconsin. In Superior, football was usually played in the bitter cold, but in sunny California he could watch football in a short-sleeved shirt.

By November of 1941, Richard and his fellow cadets were ready to move on to the final stage, advanced flight training at Luke Field in Phoenix (fee niks), Arizona. Little did they know that just one month later the Japanese would attack the American naval base at Pearl Harbor and the United States would enter World War II.

Very early in the morning on December 7, 1941, 350 Japanese fighter and bomber planes attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack was a complete surprise. Five American warships were sunk, and many more were damaged during the attack. Nearly 200 U.S. fighter planes were also destroyed, most of them before they ever made it off the ground. Worst of all, more than 2,400 people were killed, and more than 1,200 were wounded. They weren’t just soldiers. They were doctors, nurses, and people who weren’t even in the military. The United States had never been attacked in such a brutal manner before, and people across the country were shocked by the news. America had tried to stay out of World War II, but the very next day President Franklin Roosevelt (roh zuh velt) asked Congress to declare war on Japan. A few days later, Germany, Japan’s ally, declared war on the United States. This forced America to enter World War II in Europe.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor shocked and angered Americans.

Richard was ready to fight. His skills as a pilot were top-notch. Many of the cadets considered Richard the best flyer at Luke Field. When an experienced army pilot arrived at Luke with the new Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane, Richard’s friends set up a flying contest between the 2 pilots. The P-38 was faster than Richard’s AT-6 training plane, so many of those watching expected him to lose. Just the opposite happened. The Lightning’s pilot tried all sorts of maneuvers—spins, steep dives, and sharp turns. No matter what he tried, Richard’s plane ended up right behind him, in an easy position to shoot him down. There was no question that Richard Bong was one of the most gifted pilots in the Army Air Force.

Like most pilots, Richard wanted to serve his country. After Pearl Harbor he and his friends spent many hours talking about the war and imagining what their part would be. After graduation in January, many of the pilots were stationed at fighter training bases. They quickly moved on to combat jobs in Europe or in the Pacific. Not Richard. He was asked to stay at Luke Field and serve as a flight instructor for new cadets.

The P-38 Lightning was a fast and powerful fighter plane.

At first Richard was disappointed. He had gone through training to become a combat pilot, not to teach others how to fly. Instead of moping around, however, he quickly decided to make the best of it. At least he was still flying, and the extra practice would make him more ready if he ever made it into combat. Besides, he was still serving his country by helping other young pilots become top-notch flyers. His time for combat would come soon enough.

Richard quickly learned that instructing other pilots was even more difficult than learning to fly himself. He had struggled to fly at night and to stay in tight air formations, but to teach pilots in training to do these things was a true challenge. Richard wrote his mother, “The fastest way to recognize your own weaknesses is to try to teach someone else.” His greatest fear was that one of his students would get hurt or be killed because he failed as a teacher.

None of Richard’s cadets died, but many other student pilots did lose their lives. One awful night, 5 airplanes and 4 cadets were lost during a terrible crash. Richard loved the danger and excitement of flying, but accidents such as these made him realize how close he was to death every time he stepped into an airplane.

Richard enjoyed the beauty of the Grand Canyon from his training plane.

Despite the constant dangers, Richard could not resist the urge to push his flying skills to the limit. He loved “hedgehopping” at 100 feet above the ground on search missions, the treetops flashing past at 300 miles per hour. Instead of simply enjoying the beauty of the Grand Canyon while flying overhead, he flew inside its walls and turned loops. Although he was a quiet person on the ground, his wild side came alive in the sky.

Richard’s job as an instructor ended suddenly in May 1942. That’s when he was told to go to Hamilton Field near San Francisco, California. There, he would go through fighter training to prepare for duty. Richard was excited at the chance to fight. Just as he predicted, in only a few short months his career as a fighter pilot in the South Pacific would begin.