A Reluctant Hero Comes Home

Richard Bong was one of the most talented pilots in the history of the U.S. Army Air Force. He had superior eyesight and often saw enemy planes before his fellow pilots did. He could land on dirt airstrips during storms, fly just a few feet above the trees, and sneak up on an enemy with the sun behind him. Other pilots were better shots, but few were better at getting close behind an enemy before firing. His advice to new pilots was, “Get close and shoot lots of lead.” That’s exactly what he did.

Another reason Richard was so successful was his complete mastery of the P-38 Lightning. He knew exactly what his plane could do and rarely made a mistake when flying it. In combat, he pushed his plane through dozens of maneuvers that usually put him just where he wanted to be.

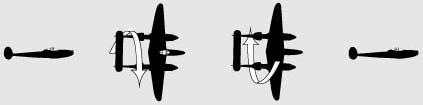

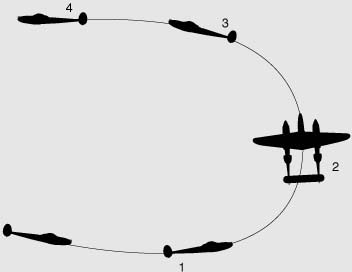

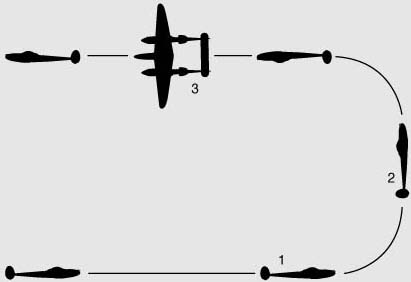

Richard was a highly skilled pilot. He spent hours learning flying maneuvers like the barrel roll, the chandelle (shan del), and the Immelmann (im uhl muhn). Richard used these and many other tricks when fighting for position against Japanese planes.

A barrel roll was a corkscrew twist that confused an enemy tailing behind.

Chandelles were climbing turns that led to deadly spins if done incorrectly.

An Immelmann was a half loop and half roll that allowed pilots to get above an enemy and turn toward them.

Fortunately for Richard and his fellow pilots, the Americans had several advantages (ad van tij is) over the Japanese. Their planes were tougher and harder to shoot down. American planes had special fuel tanks that did not explode when struck by bullets. They also had more powerful weapons that destroyed the enemy planes with only a few hits.

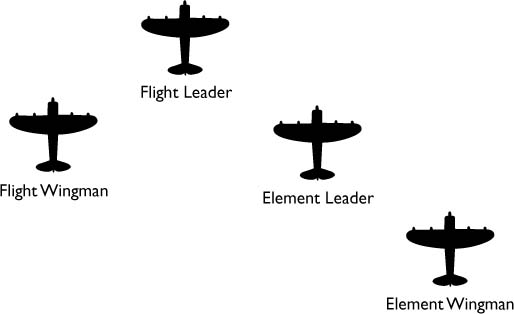

Just as important, American pilots worked better as a team than the Japanese pilots did. The Japanese flew in 3-plane formations called shotai (shoh tı), but once a battle started the formations quickly fell apart, and the pilots often ended up fighting alone. American pilots almost always worked together. Two pairs of planes called a Finger Four flew together and protected each other. Each pair had a leader and a wingman. The wingman flew behind and to the side of his leader to guard against attacks from behind.

The Four Finger formation helped American pilots protect one another.

The Americans also used radios and radar to plan their attacks. Pilots constantly talked to each other and to the flight coordinator at their base who kept track of the enemy’s movements on the radar screen. The Japanese rarely used radios and so could not communicate with each other once a battle had begun. They also had poor radar systems and were not able to prepare for attacks like the Americans did.

Working at a radar station, this soldier helped locate enemy planes.

By October Richard had 17 “victories,” the word used to describe how many planes a pilot had shot down. This was more than any other pilot in the war, a fact that made him famous back home in America. Only Eddie Rickenbacker, who had shot down 26 planes during World War I, had more. Newspaper reporters often asked Richard to talk about his victories. But Richard didn’t really care about beating out his fellow pilots or about becoming a hero in the United States. He was a quiet person and preferred spending time with his fellow pilots rather than talking with reporters. He especially hated it when reporters called him a “killer.” Richard believed he was doing his job and serving his country and certainly did not enjoy killing anyone.

What did get Richard excited was the idea of going home. General Kenney told him he would get a 2-month leave after his twentieth victory. Richard wrote home to his mother with the good news. He told her he hoped to be home by the opening of deer-hunting season in November.

On November 5, Captain Bong downed his twentieth and twenty-first planes. Just 2 weeks later, Richard was back in the United States. His first stop was in Washington, D.C., where he had dinner with General Hap Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces. He enjoyed the fancy meal and the chance to meet General Arnold, but he wanted to be home. Richard requested that he be allowed to take the train to Chicago that same night and was headed toward Poplar early the next morning.

Carl and Dora Bong were very proud of their oldest son.

The Bong family home buzzed with excitement as a crowd waited for their hero’s return. Richard’s family squeezed together with newspaper reporters, veterans from World War I, Richard’s college professors, and even 29 members of a local band. Richard’s sister Nelda played the piano, and the group sang songs while they waited. At 1:15a.m., an exhausted Captain Bong arrived. The cheering, hugging, and laughing lasted for more than an hour. Finally everyone went home, and Richard got to sleep in his own bed.

The next few weeks were spent eating his mom’s cooking, sleeping late, and catching up with family and friends. Every time Richard entered a restaurant or the Poplar hardware store he was surrounded by people wanting to hear his war stories. He was always polite and cheerful. But he was much more comfortable when it was just his family and closest friends around.

Richard’s brothers and sisters crowded together to hear his war stories.

The most annoying part of being a war hero was the newspaper reporters. They constantly called the house and asked the same questions over and over again. They even wrote stories about his family and asked his parents questions about their heroic son.

Even a trip to the hardware store drew a crowd for this war hero.

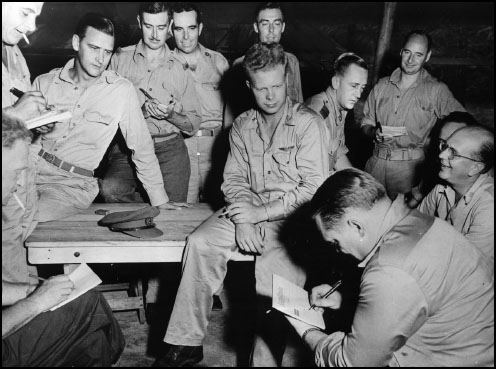

Reporters listened intently when Bong retold another one of his victories.

When hunting season began, the Bong family came up with a trick to keep the reporters away. They knew the newspapers wanted a picture of Richard with a successful kill. Finding and shooting a deer could take many days, and Richard did not want the reporters following him around Poplar’s woods. On the first day out, Richard’s father shot a large buck. The family pretended Richard had shot the buck, and he posed for pictures as it hung in his yard. The next day the newspapers had their picture of the successful hunter, and Richard and the Bong family had the woods to themselves.

Richard was also asked to crown the king and queen at the homecoming dance at the college he had attended. He did not like to dance or speak in public, but he politely agreed to appear. This was a good decision. At the dance he met a pretty young woman named Marge Vattendahl (vat uhn dahl). He had his sister Jerry ask Marge to go on a date with him, and a couple of nights later they went out with Jerry and Richard’s friend Pete for dinner and bowling. Marge and Richard got along great. At first she was nervous about being with a famous war hero, but Richard’s humble nature soon made her feel comfortable. She asked him to tell her about the many medals and ribbons on his uniform, and he replied, “Darned if I know. Someone just pins those things on me from time to time and I keep on wearing them.”

Richard pretended he had shot this buck so reporters would leave his family alone.

The couple went on many more dates over the rest of Richard’s leave. The most memorable was a flight in a Piper Cub airplane Richard borrowed from the Superior airport. Richard’s mother was also invited along, and the 2 women held hands as Richard turned steeply and flew low over the Bong farm. Marge screamed as the plane passed just over the row of evergreen trees Richard had planted as a boy. Richard sang songs to calm his passengers down and landed safely at the Superior airport.

Richard and Marge enjoyed every minute they spent together.

When he wasn’t with Marge or his family, Richard spent most of his 2-month leave performing duties for the military. He spoke at rallies where U.S. war bonds were sold to raise money for the war. Richard hated talking to crowds and said, “I’d rather have a Zero on my tail than go through all these speeches and dinners.” But he knew that raising money was important, so he did his job without complaining. Even though he was not a great speaker, people listened. At one rally, he raised more than $250,000 for new airplanes, ships, and other vital war supplies.

People crowded the streets of Superior for “Richard Bong Day.”

In January, the town of Superior celebrated “Richard Bong Day” with a parade. People lined the streets in below-zero-degree weather just to see Richard ride past in a convertible. The marching band members had to stay home because their lips would have frozen to the horns in the extreme cold! Richard reluctantly left Marge the next day, her high school photo tucked in his wallet.

Captain Bong traveled to California for a tour of Hollywood before returning to duty. He sang with the popular singer and actor Bing Crosby on the radio and met dozens of movie stars. He was thrilled when actors whom he had watched on the big screen asked him for autographs instead of the other way around. Richard flew back to New Guinea on January 29. It was difficult to leave his family and his new girlfriend, but he was excited to get back to work. No one imagined that breaking an old flying record would bring him back to Poplar just a few months later.

In Hollywood, Bong met movies stars such as comedian Jack Benny.