Ace of Aces

![]()

One of the first things Richard did after returning to New Guinea was to ask his friend Captain Jim Nichols to paint a giant-sized version of Marge’s photo on the nose of his P-38. The picture of Marge was surrounded by Japanese “Rising Sun” flags, marked with a red “O,” to stand for all of the planes Richard had shot down. When newspaper reporters started taking pictures of the “Marge” plane, he wrote to her: “I hope you don’t mind having your picture on my plane. You’re the most ‘shot-after’ girl in the South Pacific.” Soon, Marge was famous not just in the Pacific but all over the world as her picture was carried in dozens of newspapers and magazines.

Richard gazes up at Marge’s picture, painted on the side of his P-38.

The reporters followed Richard’s every move as he closed in on the all-time record for planes shot down. They hoped he would beat Eddie Rickenbacker’s record of 26 victories from World War I. Richard and several other members of the Fifth Air Force were quickly closing in on this record. The first to break it would be called “Ace of Aces” and would be in the history books forever.

One of Richard’s main competitors for the record was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lynch. The 2 men were friends. After Richard’s return, they were stationed together at the Nadzab airstrip in northeast New Guinea. General Kenney knew Bong and Lynch were 2 of his best pilots and allowed them to form a special 2-man fighting team. They called themselves the “flying circus” and flew on attack missions with other squadrons or went out by themselves on patrols.

Bong and Lynch soon proved themselves a deadly fighting team. In 3 weeks, Richard went from 21 to 24 victories and Lynch from 16 to 20. They achieved these victories by attacking large numbers of enemy planes and by always protecting one another when in danger. As always, Richard was modest about his successes. In March he wrote his mother, “I downed two planes without sticking my neck out too much.” In reality, he and Lynch had attacked 8 aircraft and narrowly escaped being killed.

Richard was one of the most talented pilots in the Army Air Force.

Like many American pilots, Bong and Lynch mastered a few simple rules for defeating the small and agile Japanese planes

Rule 1: Stay above the enemy. The P-38 Lightning climbed quickly to high altitudes. Bong and Lynch loved to fly high above the clouds, at 20,000 feet or more. There they waited for groups of Japanese planes to approach from below. When the Zero or Oscar pilots least expected it, the P-38 pilots would swoop down on them and scatter the Japanese formation in all directions. If they missed their targets on the first pass, the pilots climbed to get above the enemy and try the same thing again.

Rule 2: Always fly fast. The Japanese airplanes worked best at speeds of 250 miles per hour or below. Any faster, and the Japanese planes could not twist and turn easily. Once the P-38 pilots learned this, they did their best never to let their airspeed go below 300 miles per hour during combat. This meant not spinning and changing direction too much, because fancy maneuvers slowed the planes down. When an enemy was behind them, Bong and Lynch kept their high speeds and tried not to panic. If all else failed, sometimes they turned and flew directly at the enemy. They hoped the P-38s’ firepower would win in a head-to-head battle.

Rule 3: Always pay attention. P-38 pilot Tommy McGuire (muh gwır) often said, “It is the one you don’t see that gets you.” During combat, it was easy for pilots to concentrate on the plane they were attacking and forget about the rest of the sky. This was dangerous because unseen enemies could attack at any time. The pilots who survived many combat missions were those who had “eyes in the back of their head.” They always knew what was going on around them. Richard Bong was a master of this rule and often saw enemies that other pilots hadn’t noticed.

Rule 4: Don’t waste ammunition. One of the biggest mistakes made by new pilots was to begin firing at an enemy too early. Hitting a plane moving 300 miles per hour while your plane is moving in a different direction is a nearly impossible task. Many pilots wasted all of their thousands of bullets without even scratching their targets. For Bong and Lynch, the solution was clear: “Get in so close you can’t miss and pull the trigger,” Richard said.

Unfortunately, bad luck caught up with Lynch after just a month of flying with his friend. Guns from a Japanese ship hit Lynch’s plane as he flew over them during an attack. Lynch ejected from his plane. But his parachute did not have time to open, and he was killed. Richard’s plane was also badly hit. He made it home with 87 bullet holes in his plane. Richard was crushed to lose his friend. Lynch had taught him a great deal about flying, and the 2 men had spent time together in the air and on the ground. He would lose many friends during the war, but few were as important to him as Tom Lynch.

Just a month later, Richard shot down 2 Oscars and broke Rickenbacker’s record with his twenty-sixth and twenty-seventh victories. He was now America’s “Ace of Aces.” He was also promoted from captain to major. Reporters followed him around his tent for days, taking photographs and asking questions. Richard became so tired of the reporters that he began buzzing low over their tents, usually early in the morning while they were still sleeping. He wrote home to his mother, “I broke the record and by so doing procured for myself a lot of trouble.”

The good news was that becoming “Ace of Aces” meant another visit home. Some of the generals were concerned they might lose their new hero if they allowed him to keep flying. Others thought he could help the country even more by traveling around the United States and selling war bonds. Whatever the reasons, Richard was happy to be heading back to Wisconsin, to the family farm, and to Marge.

Bong enjoyed being “Wisconsin Governor for a Day.”

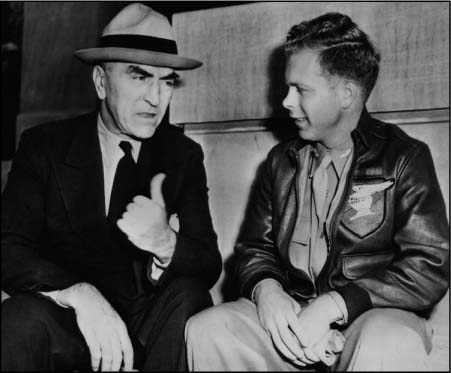

Before he could go home to Poplar, Richard had to fulfill his responsibilities as a famous war hero. He held a press conference in Washington, D.C., where he answered the questions he had already been asked so many times before. Richard was bored by the press conference. The only fun part was when Eddie Rickenbacker arrived. Bong and Rickenbacker snuck away from the crowd and sat outside where they could talk alone. Richard loved meeting the World War I ace. The 2 men traded stories, and Rickenbacker wished Richard good luck during the rest of the war.

Aces Eddie Rickenbacker and Richard Bong trade stories.

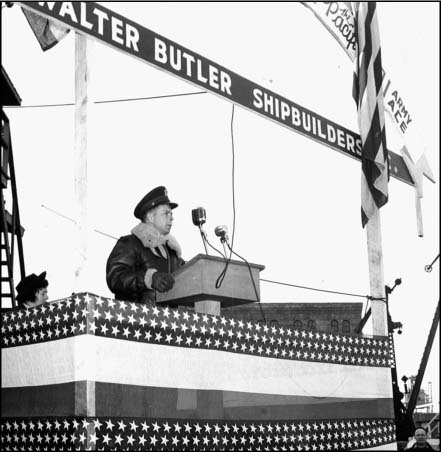

Bong never enjoyed speaking before crowds even though he had to do it often.

The next day Major Bong visited the U.S. Senate. The senators gave him a standing ovation, cheering for several minutes. Honored but also embarrassed by all the attention, he was glad when his duties in Washington were finished and he could get on the train for Chicago.

Captain Bong signs an autograph for a welder.

Soon he was back in Poplar with his family and Marge. He could not escape attention for long, but he did find a quiet country road for a special moment with Marge. Richard asked Marge to marry him. She immediately agreed.

The couple had little time to celebrate their engagement. Just a few days later Richard was off to help sell war bonds in 15 states. He flew a P-38 all around the country and gave speeches at dozens of events. Richard met with many flying cadets and gave them advice about how to succeed in the war. He also found time for some fun. While flying in Milwaukee, Richard buzzed right between buildings over busy Milwaukee Avenue. Windows rattled and heads turned as his P-38 roared through downtown and then disappeared over Lake Michigan.

Next, America’s leading ace next went to Texas for a month-long gunnery course. Some pilots would have complained about going back to school to learn how to shoot, but Richard was happy to take the course. He humbly called himself the “lousiest shot in the Army Air Force.” During the course, the pilots learned about the latest techniques for “deflection shooting.” This meant shooting ahead of an enemy so he would fly into the stream of bullets. Richard later said he could have greatly increased his number of victories if he had taken the course earlier.

Richard was made a gunnery instructor and sent back to California to teach other pilots how to improve their flying and shooting. Although he was often in the cockpit with his students, he had promised General Kenney he would fly safely and shoot at the enemy only if they shot first. His promise did not last long. Soon he would be involved in some of the fiercest air combat of the entire war.