It had already been a trying season for the Dawsons. First there was the preseason hand injury, and subsequent infection. Then the knee injury in Boston, and the manic week of decision-making before Len had declined surgery, against Jackie’s wishes. His recuperation was uncomfortable and distracting, and after sitting home on the couch one week, he was relieved when Stram asked him if he wanted to travel with the team.

Reynolds had been right, and Dawson’s knee recovered without surgery. Against San Diego, he had started again and was effective. What lay ahead was a big week—the Chiefs playing on national TV at Shea Stadium in New York against the defending world champion Jets.

In Stram’s remarks to the squad that Thursday, November 13, he underscored the size of the stakes. “Make sure that you are very careful what you say to the press,” he said. “People are calling from all over the country. Make sure that you emphasize the fact that we are a football team and we are winning because we are a football team . . . A writer from Sports Illustrated is also here to do a story on us. He will be traveling with us. Make sure that you are very careful what you say.”

That same day, the Dawsons moved from their home on 117th and Cherry (sold to Ed Budde), to a new home in south Kansas City, in Country Lane Estates, between State Line and Wornall Road. The next evening, Dawson was back from practice and home between the two nightly sportscasts he gave, when he got a call from his brother that their father—back in Dawson’s hometown of Alliance, Ohio—had just died of a heart attack.

While weathering the news in his usual stoic manner, Dawson reassured Stram that he’d travel with the team to New York Saturday, play the game Sunday, and only then travel to Alliance for his father’s funeral. “There was never any doubt whatsoever that he would play the game,” said Goldie Sellers. “That was Len, that was who he was.”

The morning of the game, in a little diner close to the hotel where the Chiefs were staying, the announcer Tom Hedrick joined Buck Buchanan, Jerry Mays, and Willie Lanier for breakfast.

Hedrick observed the players seemed more tense than usual and thought he noticed a couple of them with trembling hands.

“Guys, did you have too much caffeine this morning?”

Buchanan and Lanier exchanged a look.

“It’s not the coffee,” Buchanan said. “It’s Joe Willie.”

Namath and the defending champs would be the biggest test of the season thus far, both for the defense and the Chiefs as a whole. Like Kansas City, the Jets had won six straight games.

Thirty-three years later, Brett Favre would be canonized on ESPN for his Monday Night Football performance in the wake of his father’s death. But on this day, under nearly identical circumstances, a game played less than forty-eight hours after learning of his father’s death, Dawson was simply superb, throwing for 285 yards and three touchdowns, all of them to Otis Taylor.

In front of the largest crowd in the ten-year history of the American Football League (63,849), Dawson’s impact would be felt quickly. On the first play from scrimmage, Bobby Bell recovered an Emerson Boozer fumble. With the ball on the Jets eighteen-yard line, the Chiefs lined up in a formation they’d never shown before, the GT Slot (also known as the camouflage slot) in which the flanker Taylor, lined up slightly behind a gap between the right guard and right tackle. The tight end Arbanas lined up on the left, with Gloster Richardson split farther out to the right. At the snap, as the Jets’ secondary tried to sort out their coverage assignments, Taylor leaked out to the left. ”I didn’t even know Lenny was throwing to me,” said Taylor afterward. “He was looking right and under a hard rush. Then he just kind of flang the ball to the left, and I had to run mighty hard to get there.”

Taylor, returning to action after missing the previous three games with a pulled abdominal muscle, had ninety-six yards on seven catches, with his touchdown catches coming in the first, second, and fourth quarters. It was not a coincidence that the Chiefs offense, with its most potent weapon back on the field, played its best game of the season.

Kansas City jumped to a 10–0 lead, before the Jets rallied to tie the game. But another touchdown pass to Taylor and a Stenerud field goal gave the Chiefs a 20–10 lead. As the Jets were driving late in the half, Johnny Robinson intercepted Namath’s pass.

Kansas City scored two more touchdowns in the second half to win 34–16. After the game, the Jets’ George Sauer found E.J. Holub on the field and said, “I’m glad we don’t have to play you guys every week.”

For Marsalis and Dawson, whose lockers were adjacent to each other, it had been a trying fortnight. “I told Len I felt better when people stayed away from me,” Marsalis said. “When they acted like it didn’t happen. I dress next to Len, and I didn’t say anything to him. Each time someone said something to me, I felt it all over again. This way, for a little while anyway, I could push it out of my mind and play football.”

Dawson left for the funeral in Alliance right after the game, and the Chiefs headed home with a profound sense of accomplishment. At 6:25 p.m., the captain of the chartered jet returning the Chiefs home announced that the plane was traveling over Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, Namath’s hometown, prompting laughter and applause. The offensive linemen, who hadn’t allowed a sack of Dawson, earned an invite for a steak dinner at the home of offensive line coach Bill Walsh.

Four days later, the Chiefs were on the cover of Sports Illustrated, with Dawson in front of their distinctive choir huddle, and the headline, “THE CHIEFS PAINT NEW YORK RED.” Writer Robert F. Jones focused on Stram’s multiple offensive variations: “When it comes to camouflage, the Viet Cong are a bunch of taxi-squadders compared to Coach Hank Stram and his Kansas City Chiefs.”

It was the first time in the national press that the Chiefs egalitarian racial make-up was mentioned. “We’re almost weirdly compatible,” said Jerry Mays. “The ratio of black to white is 8-3 on defense, and we have nothing but mutual admiration for one another. There’s a strange sort of confidence evident here—a poise that we never had before. Last year, you could feel it on its way to happening, and now we finally have the talent to match the earlier effort.”

Standing at 9-1, the Chiefs were perfectly positioned to close out the division and earn home-field advantage throughout the AFL playoffs.

All they had to do was something they’d failed to do on five of the previous six occasions: beat the Oakland Raiders.

In front of the largest crowd in AFL history, Taylor made his third touchdown catch, to put the Chiefs up 34–10.

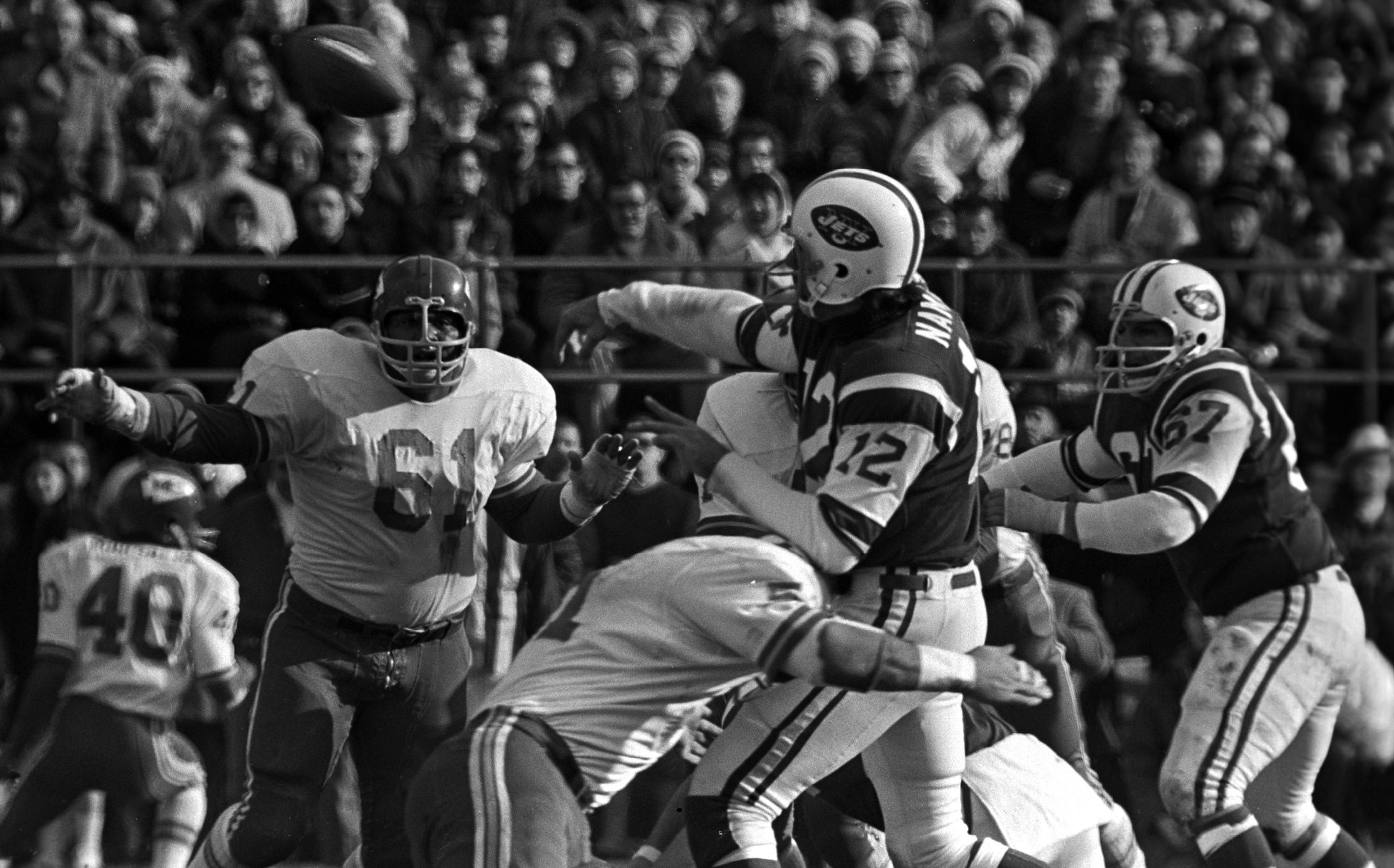

Stram and Dawson unveiled a new formation—the “camouflage slot”—on offense, while the Chiefs defense harried Namath.

After the game, E.J. Holub stuck around to sign autographs for fans at Shea.