After consecutive road wins over the defending world champions and the team with the best record in pro football, paced by a stifling defense that allowed just thirteen points over those two games, Kansas City might have been regarded as a formidable opponent for the champions of the National Football League. Instead, the Minnesota Vikings were installed as a thirteen-point favorite by Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder on the Monday before the game.

One headline in Pro Football Weekly noted that, “If It’s a Battle of the QBs . . . Kapp Has It All Over Dawson.” Elsewhere in the paper, William Wallace backtracked again on his preseason forecast, and predicted a 31–7 Vikings win, adding, “the Kansas City team lacks a top-notch quarterback like a Joe Namath, or even a Daryle Lamonica, to beat a defense as strong as the one the Vikings have been putting on the field for 22 straight weeks.”

So the buildup to Super Bowl IV played out in eerie parallel to the previous year, with a seemingly invincible team from the NFL being put forth as a heavy favorite, and the merits of the AFL entry largely ignored in the calculation.

“They’re doing it again,” warned the Raiders’ George Blanda during the week. “They haven’t learned a thing since last year. They’re underestimating the AFL all over again.”

With only a week between the league championship game and the Super Bowl, Monday was a quick turnaround day—the team was in Kansas City for just 15 hours before leaving for New Orleans. The trip to the Super Bowl began as inauspiciously as the regular-season trip to Oakland had—a food truck backed into the Chiefs charter plane on the ground in Kansas City, delaying takeoff by ninety minutes.

On Tuesday, the team’s first full day in atypically frigid New Orleans, Stram decided to move all the team’s practices from Tulane Stadium to the smaller Tad Gormley Field, in City Park, which he judged less likely to be susceptible to spying.

Later Tuesday, the bombshell dropped. David Brinkley opened the NBC Evening News by reporting, “A number of famous names in pro football will be asked to talk to a federal grand jury in Detroit and to tell whatever they know about gambling on sports. The pro football players asked to testify will include quarterback Len Dawson of the Kansas City Chiefs . . .”

The NBC story linked Dawson and five other pro players to a Justice Department sting of a network of bookmakers, including the Detroit bookie Donald “Dice” Dawson (no relation to the quarterback), whose address book included Dawson’s phone number. There was no evidence of any wrongdoing and no tangible assertion of anything more than a casual connection. But suddenly much of New Orleans, especially the 300 assembled writers and reporters who had descended on the city to cover the game, were buzzing about the implications of the investigation.

Pete Rozelle was on a boat in Bimini when the news hit and could do little but release a statement from the league office that evening noting that the NFL had “no evidence to even consider disciplinary action against any of those publicly named.”

Though the allegation was a shock, there had been gambling-related inquiries about the Chiefs before. A year earlier, after several Chiefs games were taken off the betting boards in Las Vegas, the league conducted an investigation, which included an interview with Dawson, as well as a lie-detector test. Rozelle was satisfied with Dawson’s innocence then and now, though none of that was clear to the hundreds of writers covering the story during the tense Tuesday evening.

With the media pressing for more answers at the Fontainebleu, and Dawson and his roommate Robinson under siege in Room 858, it was clear that the Chiefs needed to make a statement that evening. So it was left to Hunt, Stram, Dawson, and the Chiefs’ publicist Jim Schaaf to work out a response. (Schaaf generated goodwill among the press corps by ordering five pounds of shrimp remoulade and lump crabmeat in the Chiefs press headquarters; the writers would be waiting for hours, but they wouldn’t go hungry.)

At 11 p.m. that evening, Stram and Dawson entered a packed press room, and Stram announced that Dawson would make a statement but take no questions.

“My name has been mentioned in regard to an investigation conducted by the Justice Department,” Dawson said. “I have not been contacted by any law enforcement agency or apprised of any reason why my name has been brought up. The only reason I can think of is that I have a casual acquaintance with Mr. Donald Dawson of Detroit, who I understand has been charged in the investigation. Mr. Dawson is not a relative of mine. I have known Mr. Dawson for about 10 years and have talked with him on several occasions. My only conversation with him in recent years concerned my knee injury and the death of my father. On these occasions he called me to offer his sympathy. These calls were among the many I received. Gentlemen, this is all I have to say. I have told you everything I know.”

In the end, that’s all there was to the story. Neither Dawson nor the other players were ever subpoenaed. Rozelle arrived in New Orleans on Wednesday and coolly conducted an hour-long press conference in which he defended Dawson’s honor as well as the league’s security investigation. Regardless, the furor didn’t immediately go away, and Dawson was left to face the biggest game of his life under a cloud of suspicion.

His teammates rallied around him, and the ones who knew him best weren’t beyond needling him. When Dawson walked into the team breakfast the following morning, Fred Arbanas was talking to fellow Motor City native Ed Budde, and Arbanas said, “Didn’t you ever learn not to get involved with people from Detroit?”

“Hey, Len,” asked E.J. Holub, “Can you book a bet for me tonight?”

•

While having a team’s starting quarterback implicated in a nationwide gambling investigation wasn’t ideal preparation for a Super Bowl week, the Chiefs had already been through worse. By Wednesday evening, after watching the Vikings on film and receiving the game plan, there was a growing sense of confidence throughout the team.

Defensive assistant Tom Bettis spent the week showing the Chiefs Minnesota’s offensive variations, all modifications on vanilla. The team had seen twenty sheets of offensive formations before the game against the Raiders; they received just four pages for the Vikings. On the Wednesday before the game, Jerry Mays walked out of a meeting room and saw assistant PR man Will Hamilton walking down the hall and told him, “If Jan-ski can make three field goals, we’re going to win the game. There is no way they’re going to score more than a touchdown.”

On the offense, there was confidence in Stram’s game plan, which focused on double-teaming the Vikings ends, and passing in front of their cornerbacks, who played off the line of scrimmage, giving receivers a much larger cushion than most AFL secondaries.

Later in the week, Lamar Hunt’s longtime friend Buzz Kemble cornered Stram and asked him pointedly, “Really—no bull—what do you think?” When Stram answered confidently, Kemble decided to increase his wager on the Chiefs. Even the players were convinced. Aaron Brown contacted Ray Whitlow, his former teammate at Minnesota, and asked him to put down a series of $500 bets, with instructions not to take the points but instead to take the odds on an outright Chiefs win.

Amid the Chiefs’ growing confidence, there were injury concerns. Marsalis was only released from the hospital in Kansas City that Wednesday, flying to New Orleans that night. Robinson, with his torn rib cartilage, was in pain and didn’t practice at all during the week. But the Louisiana native and LSU alum was adamant.

“I’m playing,” he told his coaches. “It doesn’t matter what happens.”

On Saturday, during the final walk-through, Curley Culp hit Moorman harder than Moorman considered strictly necessary. On the next play, Moorman hit Culp harder than Culp considered strictly necessary. After two more plays of one-upmanship, Stram blew his whistle. “All right! That’s enough! Let’s take it inside.”

The weather had continued to deteriorate, and at one point in the week, the fountain in front of the Chiefs hotel was frozen solid. But people came to New Orleans anyway, and the flow of fans and media overwhelmed the city’s lodging. Some of the staff cameramen at NFL Films had to sleep in empty beds at a local hospital. A group of Chiefs fans who drove down from Kansas City for the game couldn’t find lodging anywhere and wound up sleeping in their cars in the parking lot of the New Orleans Airport.

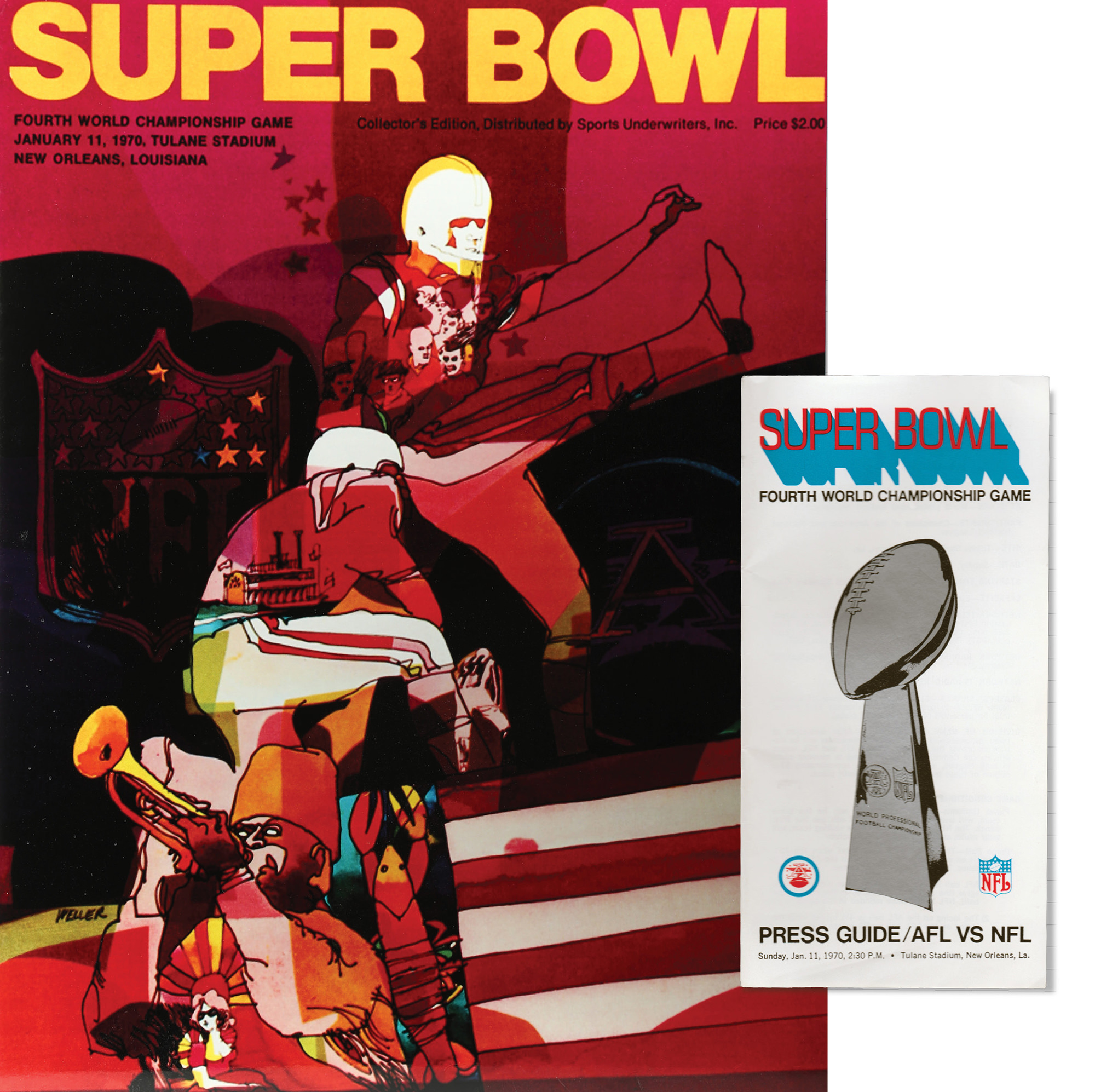

After debuting in Los Angeles, and two games in Miami, the fourth Super Bowl came to New Orleans for the first time.