It rained Saturday night, but Sunday morning was overcast and windy with inclement weather, at one point even a tornado watch in the forecast.

Lamar Hunt spent part of the morning at an NFL brunch, featuring the Tonight Show co-host Ed McMahon, whose remarks ran long. Hunt was too gracious to leave during the presentation, but he bolted out as soon as McMahon concluded and headed back to the Royal Sonesta hotel in the French Quarter, to pick up Norma.

Lamar and Norma collected their things and left their hotel room. When the elevator door on the fourth floor opened, they saw the tense, alarmed faces of Vikings owner Max Winter and his wife, Helen. After the short, nervous hellos, the two couples rode down the first floor in uncomfortable silence. There was no mention of the game, or of the shared history a decade earlier when Winter had abandoned the AFL to jump to the NFL.

After reaching the lobby, the two couples exchanged goodbyes and went their separate ways. As they moved away from the elevators, Lamar’s walk grew more relaxed and he cast a brief sidelong glance at Norma. With the barest hint of a smile, he said, “We’re going to win today.”

She looked questioningly back at him and asked, “How do you know?”

“They’re even scareder than we are.”

Three years earlier, before Super Bowl I, Stram had tried a motivational ploy that failed miserably—putting a set of Mickey Mouse ears in front of each player’s locker, in reference to the NFL’s view of the AFL as a “Mickey Mouse league.”

In New Orleans, the players were greeted with a more subtle, effective form of inspiration. When they entered the locker room, they found a small addition to their game jerseys, an anniversary patch denoting the ten-year history of the AFL, sewed on the left shoulder. (All 16 NFL teams had worn a patch commemorating the league’s fiftieth anniversary throughout the 1969 season; the AFL loyalist Ange Coniglio, in Buffalo, had written Lamar Hunt, persuading him to honor the AFL’s ten seasons with a patch.) “It was incredible to see the reaction of those great players,” said Hank Stram. “They were so proud to wear that patch because they cared about the league. They wanted to be first-class.”

“It lit us up,” said Lanier. “We knew what it all meant.”

In the hours before the game, the Chiefs were confident and keyed up, but not, in E.J. Holub’s description, the “blithering idiots” they were prior to Super Bowl I. Dawson, who’d slept miserably the night before, ate a candy bar while looking once more at the game plan in front of his locker. Ernie Ladd, who’d sat out the ’69 season while his knees healed, visited the locker room, and Stram told him he could join the team on the sidelines, but only if he eliminated his facial hair. To cheers from his teammates, Ladd went into the bathroom and emerged clean-shaven. Stram wasn’t done. Less than an hour before kickoff, Bobby Yarborough approached Lanier and told him, “Willie, coach says you need to shave your moustache.” Lanier hadn’t shaved his upper lip since the AFL title game a week earlier, but now he, too, went before the mirror for a final shave.

Despite the miserable weather during the preceding week, the natives of New Orleans turned out for the game with all the festive air that one would expect from the Big Easy. There would never be another Super Bowl with more hats, more feathers, or more dancing.

As Stram walked out on the field more than an hour before kickoff, he was serenaded by New Orleans’ own Onward Jazz Band. But the jaunty tone of pregame festivities were undermined by a random bit of buffoonery; two hot-air balloons were supposed to lift off from the field before the game, but the one whose gondola rider was wearing a Viking costume was released from its moorings prematurely, and skittered across the field, crashing into the stands and injuring one of the Sugar Bowl beauty queens in attendance.

For the teams, the greater annoyance was the state of the field. Though George Toma had performed his usual artistry in field markings, the tarp that Tulane Stadium used for the field had leaked in certain areas. Once the players came out to warm up, it was clear that the field was in bad condition, slick and muddy in spots. Stenerud went back to the locker room and had Yarborough install mud cleats—1½-inch spikes—to the heel of his left shoe.

During the warm-ups, the Vikings assistant coach Jerry Burns kept looking over at Wilson and Stenerud, who seemed unfazed by the conditions, going through their pregame ritual. “I don’t believe I’d ever seen anyone kick the ball so well, so high,” Burns said. “I was in awe of their kickers. Wilson was kicking them as high as the lights. And their kicker was routinely kicking fifty-yarders.”

The three astronauts from Apollo 12 were introduced for the pre-game ceremonies, and then the actor Pat O’Brien narrated (rather than sang) the National Anthem, accompanied by Doc Severinsen’s trumpet.

At just past 2:30 central time, Stenerud teed up the football, and booted the opening kickoff through the back of the end zone. After their experience with the complex offenses of the AFL, the Chiefs had little problem with the Vikings basic attack: Minnesota ran out of just two formations, and in sixty-two offensive plays from scrimmage, they didn’t once shift or start a play with a man in motion.

“Our whole influence was Bambi and the Chargers and the things Sid Gillman was doing, like the Raiders, and the Jets, when you got an arm like Namath; that was our culture,” said Jim Lynch. “The NFL was different. Their culture was the Green Bay Packers. Theirs was, ‘Look, we’re gonna line up and we’re gonna run the Green Bay sweep. And you’d better stop us, ’cause here we come.’”

Confused by the Chiefs’ triple stack and outmuscled at the line of scrimmage, the Vikings were shut out in the first half. It quickly became clear that while the Vikings’ undersized 235-pound center Mick Tingelhoff may have been a worthy all-league selection in the NFL, where he was a quick-footed blocker free to operate in space, he was physically unequipped to deal with the head-on pressure and intimidation of Buchanan and Culp. They took turns lining up right on Tingelhoff’s nose in the Chiefs’ odd-man fronts, largely destroying the Vikings’ interior running game.

Game plans are curious things. Often ideas that seem profound in the film room on a weeknight are rendered completely irrelevant when real people try to execute them in a real game on Sunday. But in this case, Stram’s game plan worked with an almost eerie precision. The Chiefs double-teamed the Vikings’ ends, to prevent them from batting down passes, and in so doing opened passing lanes for Dawson’s play-action fakes and short, quick flares and out patterns.

Kansas City’s edge in the kicking game soon became apparent. On the Vikings’ opening drive, they had driven to the Chiefs 38 and punted. On the Chiefs’ first drive, they drove to the Vikings 41, and chose to send out Stenerud for a field goal attempt.

“I just remember all the Vikings bench staring at Jan,” said assistant John Beake. “And then he kicked the ball and all those heads moving toward the goalposts.”

The kick sailed true, from forty-eight yards out.

On their second drive, Dawson found Taylor and Pitts on short passes, culminating in a thirty-two-yard Stenerud field goal, to go up 6–0. Then two turnovers followed in quick succession, with Marsalis forcing a John Henderson fumble recovered by Robinson. Two plays later, Dawson underthrew a deep ball to Otis Taylor that was intercepted by Minnesota’s Paul Krause.

But Kansas City’s defense kept the Vikings pinned deep, and Kansas City got the ball back on the Minnesota 44. From there, the Chiefs unveiled a play designed to exploit Minnesota’s aggressive pursuit. It was an end-around called 52 Go Reverse, in which Pitts went against the flow of the offense and took Dawson’s handoff around right end. It went for nineteen yards and put the Chiefs in field-goal range again. Though the Vikings defense stiffened, Stenerud kicked his third field goal, from twenty-five yards, to make it 9–0.

Kicking into the wind, Stenerud’s ensuing kickoff hung up in the air. When the Vikings’ Charlie West, running forward, fumbled the kickoff, the Chiefs’ Remi Prudhomme recovered on Minnesota’s 19.

This was a pivotal moment; if the Chiefs could finally muster a touchdown, they would have a three-score lead. If the Vikings could hold KC out of the end zone yet again, they would feel they had weathered the storm. The Chiefs moved closer when Dawson found Taylor on the sideline for a first down at the Vikings four-yard line. But two running plays lost a single yard, leaving the Chiefs third-and-goal at the Vikings 5.

At which point Stram had an idea.

Speaking to assistant Tommy O’Boyle, who was wearing a headset to relay communications with the assistants in the booth upstairs, Stram said, “Look for 65 Toss Power Trap, see what it looks like.” O’Boyle relayed the request.

“It wasn’t really a question,” said Beake, who was up in the booth. “It was more of a statement. He was telling us he was running it.”

Stram grabbed Gloster Richardson and sent him in with the play. A part of the Chiefs’ short-yardage offensive package, 65 Toss Power Trap was a sucker play that relied on the defense to pursue aggressively the instant they saw the left tackle Tyrer pulling out to his left as if to lead a sweep. (The terminology could be confusing: “toss” didn’t refer to a pitchout—instead, Dawson would hand the ball off to Mike Garrett—but to the exchange of blocking assignments.) “I was a little surprised when I heard the call,” said Budde, “because Tyrer was one of our best blockers.”

In the huddle, as Mike Garrett heard Richardson relay the play to Dawson, then the quarterback repeat it to his offense, his eyes widened. “I just thought, Holy Shit!,” said Garrett. “Either I’m going to have a giant hole to run through, or they’re going to tear my fucking head off. That one was deep in the playbook.”

At the snap, the tight end Arbanas chipped on Jim Marshall and then moved ahead to block linebacker Lonnie Warwick. Alan Page, lined up between Tyrer and Budde, followed Tyrer through the hole he’d vacated and was two yards upfield when he recognized that he’d been had. At that point, it was already too late; Moorman was running at speed to cut off both Page and Marshall, behind him. Garrett took Dawson’s handoff and darted in behind Moorman. By the time Paul Dickson shed Budde’s initial block, he was grasping at air, and Garrett ran in the end zone, untouched.

On the sideline, Stram responded with an explosion of pure, joy—congratulating himself as much as the team. “Was that there, boys?! Was that there, rats?! Nice going, baby! Yaahah! The Mentor! Sixty-five toss power trap! Yaha! Did I tell you that baby was there?!”

The half ended with the Chiefs leading 16–0, and the NFL loyalists experiencing a dismaying sense of deja vu.

In the locker room, the Chiefs separated into units to discuss all the things that had worked and to address the few things that hadn’t. Dawson and Stram agreed not to tinker with the shotgun any more in the second half. Bettis reminded the defense that, if the Vikings had to resort to an all-out passing attack, he’d bring in Willie Mitchell as a fifth defensive back.

The intermission didn’t last forever, it only seemed that way. In one of the first instances of Super Bowl excess, the halftime show featured Al Hirt, Doc Severinsen, Lionel Hampton, Marguerite Piazza, the Southern University marching band, a series of parade floats, and then a reenactment of the Battle of New Orleans. Twenty-seven minutes elapsed from when referee John McDonough blew the whistle to end the first half until the Vikings’ Fred Cox kicked off to start the second half.

Two weeks earlier, in their playoff opener, the Vikings had trailed the Rams, 17–7, at the half and rallied to win that playoff game. But on this day, Vikings coach Bud Grant had apparently done little to adjust to the Chiefs’ tactics, merely counseling his team at the end of the half, “Go play better.” For a while they did, mounting their one sustained drive of the day. Kapp scrambled to complete four passes for forty-seven yards, and when Dave Osborn ran over from the 4, Minnesota had cut the Kansas City advantage to 16–7.

If the Vikings were going to come back, this was the time. On the ensuing drive, the Chiefs faced a third-and-seven at their own 32. Dawson again called the end-around play—52 Go Reverse—and for the third time that day, it worked. Pitts gained seven yards on the play, just making the first down. After a fifteen-yard personal foul penalty, the Chiefs had first-and-ten on the Minnesota 46.

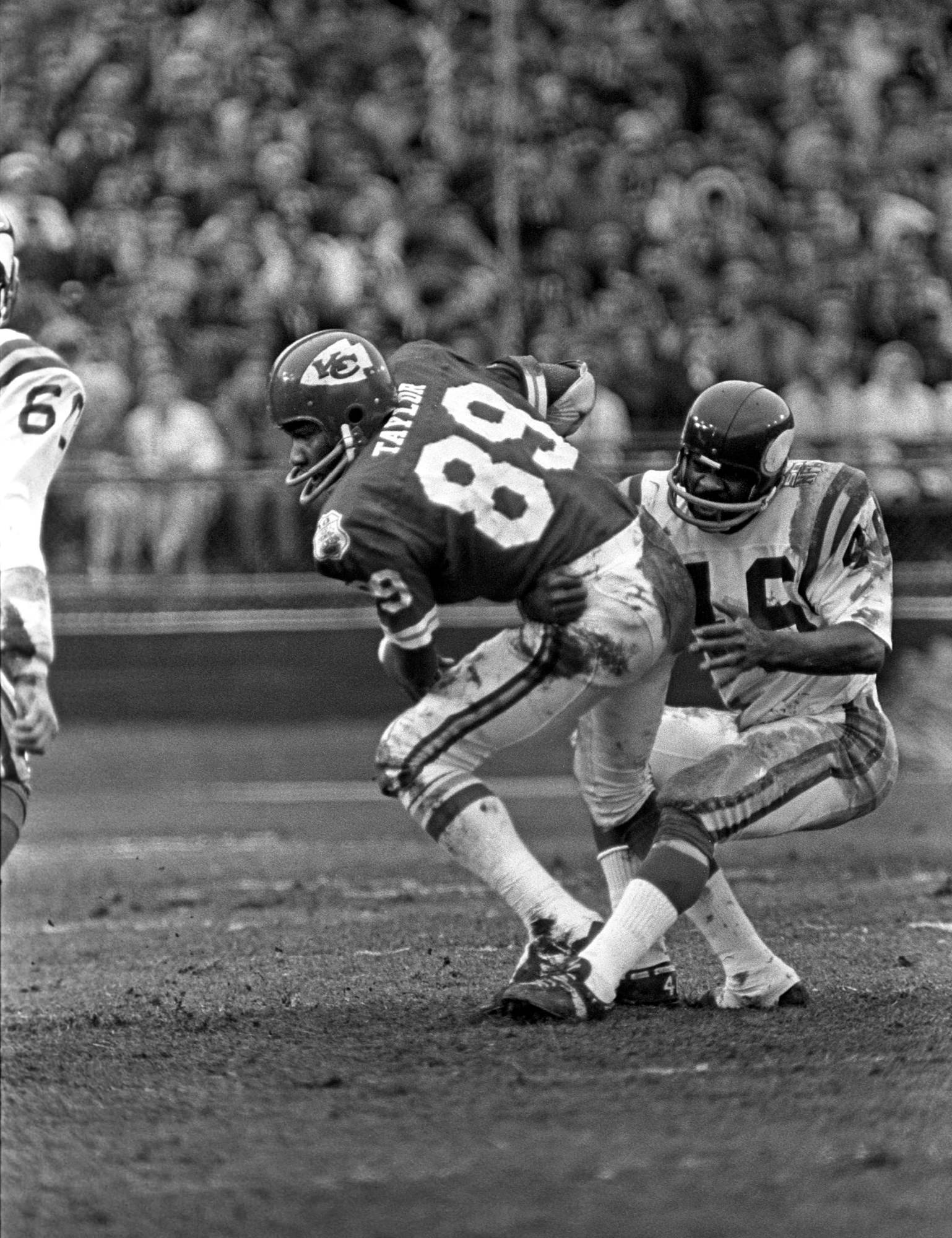

Before the snap, Dawson sensed an all-out blitz and had called the perfect play for it: a quick hitch to Taylor. After a short drop, he fired the ball into the flat just as he was being hit. Taylor caught the pass, and turned upfield, breaking the attempted tackle of cornerback Earsell Mackbee, then sprinted down the sidelines in his long, prancing stride. Karl Kassulke had an angle on him at the 10, but Taylor’s juke move and stiff arm left him on the ground.

As Taylor ran to the end zone, in the midst of the cacophony that greeted the biggest play of the game, he could distinctly hear the voice of his mother, Lillian, in the stands, shouting, “That’s my baby!”(Cheryl Anderson, Taylor’s wife at the time, was standing next to Lillian; “That’s when you know you’re a mama’s boy,” she said. “When you hear her voice out of 80,000 people.”)

With the Chiefs up 23–7, and the outcome no longer in doubt, the rest of the game was a slow accretion of details leading to the inevitable final result. The Chiefs defense intercepted three passes in the fourth quarter. Both teams’ uniforms, by then, were caked in dark Louisiana mud, roughly the color of strong coffee grounds. On the Chiefs’ final drive, Dawson scrambled out of a busted play and was hit late by Alan Page, prompting a shoving match that brought players off both benches. By then, though, there was little fight left in the Vikings. Earlier in the fourth quarter, the Chiefs had knocked Joe Kapp out of the game, on an Aaron Brown hit that left the Vikings’ leader writhing in pain.

Throughout the game, the Chiefs players on the sidelines had noted something unusual about their coach’s demeanor. Stram, who was frequently animated but usually somewhat modulated on the sidelines, seemed particularly chatty on this day.

“He said to me, ‘Stay close to me,’ because I had the headset,” remembered Flores. “So I’m trying to keep up with him, and all of a sudden he’s walking back and forth all over the place, and he’s more animated and moving up and down, and I’d never seen him like that before. I finally stood in one place, and just thought, He’ll be back.”

Dawson, consulting with his hyper coach during one timeout, thought to himself, This guy is losing it; the pressure is really getting to him.

Soon, the euphoria of the moment overwhelmed all other considerations. The final play of Super Bowl IV saw Robert Holmes bulling ahead for seven yards. Then, beneath the densely packed clouds, the game clock reached 0:00, and the muddy, red-clad Chiefs ran off the field, carrying Stram on their shoulders, champions of the world.

“It was the highest of highs,” said Goldie Sellers. At the end of the game, his wife, Peaches, bypassed the hedges at the edge of the field and embraced her husband, thrilled the $15,000 winner’s share meant they were going to be able to build a house.

In the locker room, the elation emanated far beyond the forty-man roster. “We wanted to win for Kansas City,” said Garrett. “We wanted to make it more well-known than it was.” In this, the Chiefs surely succeeded. Some estimates had more Americans watching Super Bowl IV than had seen Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk the previous summer.

Otis Taylor, who’d made the key offensive play in all three playoff games, spent the first ten minutes after the game weeping, still overcome by the scale of the achievement.

Pete Rozelle presented Hunt and Stram with the Super Bowl championship trophy as Lloyd Wells sat grinning in a window well against the back wall—perfectly placed to be in every television shot of the champions’ locker room.

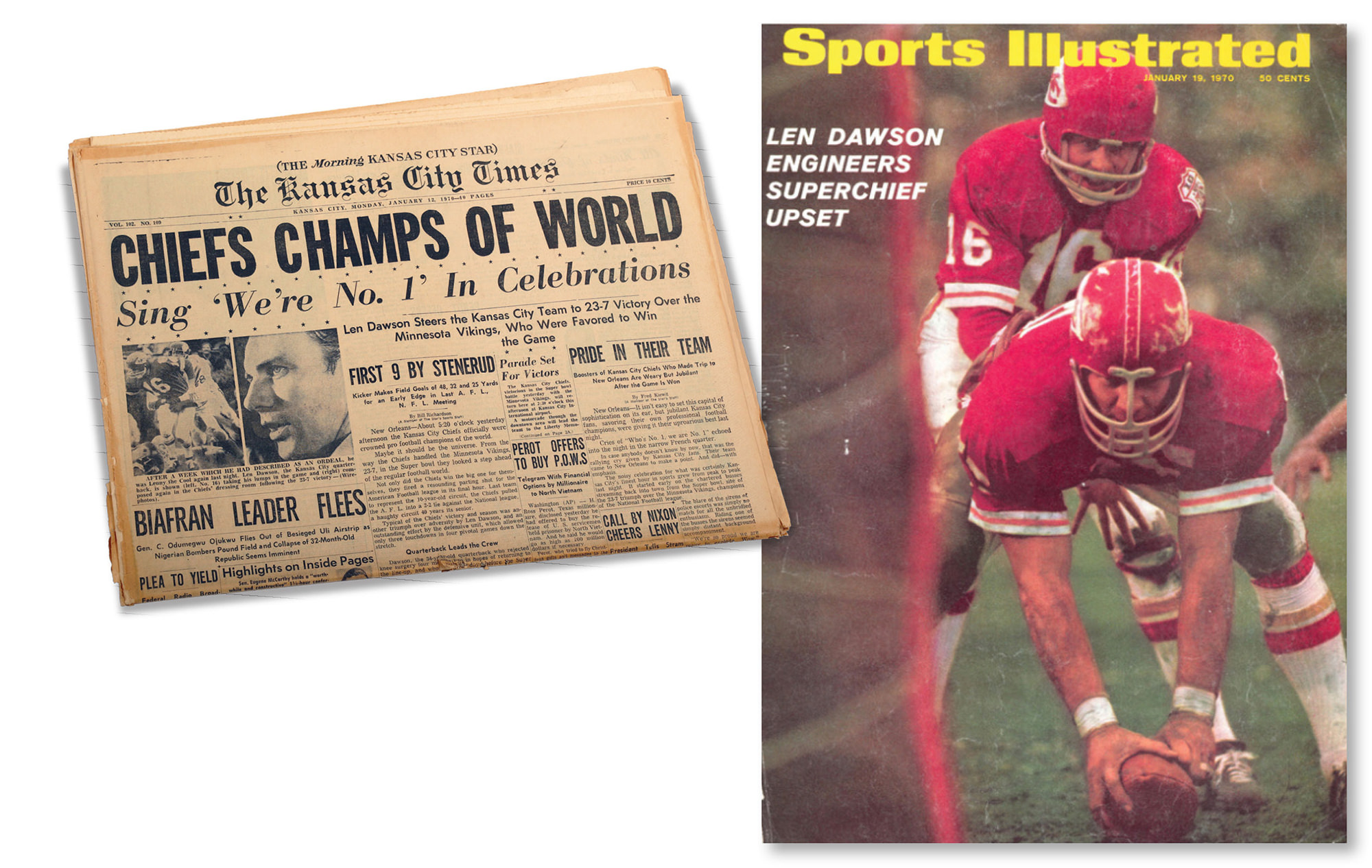

Redemption was all around the room. Dawson felt vindicated both off and on the field as he received the MVP award (and the automobile that went with it). He displayed the same outward calm he’d exhibited all week.

Then came the call.

“Hey, Lenny, come here,” said Bobby Yarborough. “The phone—it’s the president.”

“The president of what?” asked Dawson.

“The president,” exclaimed Yarborough. “Nixon!”

The short conversation that followed was a seminal moment in American sports.

“The correct spelling of my name?,” Dawson said to an operator. “D-A-W-S-O-N.” Then after a pause, the president was patched through. Dawson smiled and said, “I certainly appreciate that, Mr. President, but it wasn’t only me. It was the whole team.”

So the original Super Bowl series, NFL versus AFL, ended in a 2–2 tie and in parity between the leagues that would come together the following season.

Asked by CBS’s Frank Gifford to sum up his feelings, Hunt said, “It’s pretty fantastic. It’s a beautiful trophy, and it really is a satisfying conclusion to the ten years of the American Football League. I want to say especially a thanks to the people of Kansas City. This trophy really belongs to them as well as the organization. This team is Kansas City’s.”

Hunt and the Chiefs had come a long way since the sparsely attended exhibition opener in Kansas City in 1963.

Now, on the afternoon of January 11, 1970, the American Football League had finally earned the lasting respect it deserved. At that very same moment, it ceased to exist.

“People really thought that the Jets win in Super Bowl III was a fluke,” said Steve Sabol of NFL Films. “It didn’t really cause people to reassess things. You heard the same thing from everyone: If they played ten times, the Colts win eight or nine. But after Super Bowl IV, nobody was saying that. After that, there was no doubt anymore. You had to grant that the AFL had reached parity. At the least.”

In the losing locker room, the Vikings gave Dawson plenty of respect, but also praised the other Chiefs. Kapp compared the Kansas City front four to “a redwood forest.”

Stenerud’s influence on the game was also singled out. “Give the car to the kicker, baby,” said the Vikings Carl Eller of Stenerud’s day. “He won the game for them. After he kicked that first one, we had to know that anytime they got inside the 50, they were in scoring range.”

That evening, the Chiefs’ team party was held in the Grand Ballroom at the Royal Sonesta. Tom Flores and his wife were joined by his old Buffalo teammate, Jack Kemp, and his wife. Both men had played all ten years in the AFL and, just as the Chiefs reveled in the Jets win the year before, so it was that all the AFL players celebrated the Chiefs win to bring the curtain down on the ten-year history of the AFL.

After the Royal Sonesta party, Lamar Hunt walked the half-mile down to Jackson Square with his friends Tom Richey and Buzz Kemble. Hunt climbed up on the statue of Andrew Jackson and his horse. He wasn’t drunk; just giddy and joyous. Later that night, Hank Stram wound up at Al Hirt’s place, where he was introduced and serenaded.

For Tom Pratt and Tom Bettis, and some of the other assistants, the pinnacle was the game itself. They stayed at the Royal Sonesta party for a couple of hours, then made their way back to the Fountainebleu, got some beers, and watched the delayed telecast of the game, which had been blacked out in the New Orleans area.

Back in Kansas City, the jubilation had started immediately, and the reverberations could be felt throughout the city. Fans were dancing in the streets in Westport and the Plaza, and on Brooklyn Avenue outside the stadium. In Overland Park and Raytown, Blue Springs and Lee’s Summit, people ran outside to honk their horns, set off firecrackers, and celebrated with their neighbors. “Empty Roads, Few Police Calls Are Signs of a Town Enraptured,” was the headline in the Times.

The next day featured an astoundingly large parade in Kansas City. Though the new Kansas City International Airport wouldn’t be open to the public for another two years, the team plane landed at KCI, to avoid the chaos at Municipal Airport that followed the earlier win over the Raiders.

The streets were lined with fans throughout the last five miles on the route from KCI. The procession went down I-29, past the Municipal Airport terminal, across the Broadway Bridge, up Broadway to 10th Street, then East on 10th to Grand Avenue, before turning south on Grand to the Liberty Memorial. More than 100,000 people congregated downtown to greet the team. The parade of cars was led by Lamar Hunt, Mayor Ilus Davis, and chief of police Clarence Kelley (the future FBI director).

It was that moment, as they passed through the throng of fans and the blizzard of ticker tape, that the players got a sense of the resonance of their accomplishment. At the end of a long, difficult, and at times bitter decade, both the city and the team had joined in a celebration that was as close as most people could ever come to harmonious, unified pandemonium.

But not all the Chiefs were there for the parade. In the jubilant locker room in New Orleans, the ten Chiefs who had been named AFL All-Stars—Bell, Lanier, Stenerud, Budde, Culp, Marsalis, Tyrer, Holmes, Buchanan, and Livingston—were reminded that they would not return with the team to Kansas City, but instead fly to Houston the next morning to prepare for the final AFL All-Star Game.

A week later, when the players got back from the AFL All-Star Game, general manager Jack Steadman saw Willie Lanier at the Chiefs offices and apologized.

“I didn’t think it through,” Steadman admitted. “Next time we go, we’ll fly everybody back for the parade, and then fly out after that to the All-Star Game.”

Next time.

The Chiefs frontline—which Kapp compared to “a redwood forest”—held the Vikings’ Bill Brown to just twenty-six yards rushing.

The ten-year AFL patches on the Chiefs’ jerseys was a surprise that “lit us up,” in Lanier’s words.

Though Al Hirt (with Doc Severinsen) wore Vikings horns for the pregame show, he watched the game from the Chiefs’ bench.

Pitts had three big gains on the end-around play 52 Go Reverse, while Stenerud’s record-setting opening field goal set the tone for the superiority of the Chiefs’ specialty teams.

Garrett is congratulated by Taylor after scoring the first touchdown of the day.

The Vikings leader Kapp was ineffective in the face of the relentless rush by Brown and the rest of the defensive line.

Taylor, tackled here by Mackbee, had six catches on the day, and later eluded the same defender to put the game out of reach.

After a season of enduring adversity and agony, Stram reveled in his Super Bowl victory ride.

Dawson receives a call from Nixon, while Hunt looks on in the background.

Stram interviewed after the game with the Super Bowl trophy, which later in 1970 would be renamed the Vince Lombardi Trophy.