On Friday, June 21, 1963, the staff of the Dallas Texans loaded up moving vans and headed north to become the Kansas City Chiefs. They were a championship team seeking a home.

American Football League founder and Texans president (he carefully avoided the term “owner”) Lamar Hunt had been casting about for options during the team’s AFL title season in 1962, while absorbing another year of discouraging financial losses and fighting with the NFL’s Cowboys for the loyalties of Dallas football fans.

The move to the Heart of America had been orchestrated by Kansas City Mayor H. Roe “The Chief” Bartle, who’d heard that Hunt was searching for a new city and reached out to invite him to visit.

Bartle was a true believer in the promise and potential of Kansas City, and also an excellent salesman. He explained why the city would be an ideal place to operate a professional football team. During Hunt’s visit, Bartle offered to help start a season ticket campaign, to provide the team a favorable lease at Kansas City Municipal Stadium, and to build a facility to house the club’s offices and practice field.

Hunt was a hopeless romantic in many ways—a fan of sports, held in their thrall—but also a clear-eyed pragmatist in other respects. He had realized during the fall of 1962 that his dream of having a prosperous pro football team in his hometown of Dallas could never work because of the stalemate with the NFL’s Cowboys. The Texans had lost money even in their championship season.

Kansas City’s season-ticket drive had stalled at 15,000 that spring, but that was well above anything Hunt had accomplished in Dallas, so he agreed to the move. Hunt spent the next few weeks arguing internally that the team should keep its nickname, until his general manager, an oil-company accountant named Jack Steadman, prevailed upon him that it would be a disaster to try to launch a team called the Kansas City Texans. Hunt eventually relented and announced in May that the team would be known as the Kansas City Chiefs, in honor of both the area’s Native American heritage, and a nod to the nickname of the mayor who’d arranged the deal.

The team leader and star quarterback, Len Dawson, was back home with his wife, Jackie, in Pittsburgh, when he got the news about the move. “I mentioned to some friends that the team was going to Kansas City, and they said, ‘Kansas City, Kansas, or Kansas City, Missouri?’ I said, ‘You mean there’s two of them?’ So, I had no idea which one. The thought then, particularly back east, was, ‘Man, you’re going to a cow town. They have horses and cattle running in the middle of the main street in the city.’”

Kansas Citians, as a rule, did not wear cowboy hats or own livestock, and they could be thin-skinned about the casual perception that they did. It was the largest city in the Great Plains, boasted the oldest shopping district in America—the Country Club Plaza—as well as a rich history in jazz and blues, with giants like Charlie Parker and Count Basie spending crucial years there. Then there was the barbecue, and the hospitality. Kansas Citians prided themselves on an authentic, earthy Midwestern friendliness that was far removed in tone from the somewhat stilted formality of St. Louis, just 250 miles to the east.

The civic pride in Kansas City had a particularly earnest quality. “Everything’s Up to Date in Kansas City” was still played—without irony—around town. In the clubs and lounges, many of the rock ’n’ roll combos learned the words and music to the Leiber-and-Stoller penned Wilbert Harrison hit, “Kansas City.” It seemed part of the civic character that Kansas Citians were sensitive to slights, and eager for outsiders to see the community’s virtues.

•

On a trip to Kansas City in the spring, Hunt was introduced to his counterpart, Charles O. Finley, owner of the Kansas City Athletics baseball team.

“This is a horseshit town,” said Finley to Hunt, “and no one will ever do any good here.”

Kansas City’s feeling for Finley was mutual. The city came to loathe the baseball owner for his excessively bush-league antics, the string of losing seasons that continued under his ownership, and more than anything else, his temerity in suggesting that there might be a better place to own a sports team. Later in 1963, Finley tried to persuade Hunt to join him in moving both teams to Atlanta. The diffident Hunt politely declined; he was loathe to criticize anyone, but he did not know what to make of Charlie Finley.

Hunt was still trying to convince Stram and his players on the wisdom of the move. Many of the team’s players were from Texas, and were reluctant to relocate. Defensive end Jerry Mays had to be talked out of an early retirement. Then, on August 9, 1963, a crowd of only 5,721 showed up for the Kansas City Chiefs’ home debut, a preseason game against the Bills. “We were shocked with the attendance of that first game,” said Hunt. “It was very depressing and disappointing to see so few fans.”

Three weeks later, playing the Oilers in another exhibition, a title-game rematch held in Wichita, the Chiefs rookie running back Stone Johnson broke his neck while blocking on a kickoff return. Nine days later, he died in a Wichita hospital. Stram’s oldest son, Henry, Jr., had befriended Johnson during that first training camp in nearby Liberty, often walking into town with him for ice cream. “Dad, how could this happen?” Henry, Jr., demanded after Johnson’s death. “I thought football was just a game!”

Buck Buchanan, who’d also been Johnson’s teammate in college, had the heartbreaking duty of packing up Johnson’s belongings and sending them back to his family in Texas. Buchanan and eight more of Johnson’s teammates were there at Menger Avenue Baptist Church in Dallas on September 12, 1963, when they laid Johnson to rest. His death cast a pall over the team’s arrival in Kansas City; the defending AFL champions crashed to a 5-7-2 record and played the season in a kind of fugue state. “Abner Haynes was never the same,” said Stram of the team’s dynamic star running back.

The trouble didn’t end there. Kansas City in 1963 was a town sprinkled with mean little bars and dimly lit nightclubs, some of them still under Mafia control. Late in the ’63 season, tight end Fred Arbanas was jumped by two men at 33rd and Troost and wound up losing vision in one eye. Just months later, guard Ed Budde got in a fight in the vestibule of the Bagdad Lounge, on 37th and Broadway, and was clubbed repeatedly with an 18-inch piece of pipe. Bleeding from the ears, nose and mouth after his attackers fled, Budde somehow drove himself to the emergency room. Both injuries looked career-ending. Three surgeries could not return the sight to Arbanas’s eye and Budde needed to have a plastic plate put in his head. But there was a resolute toughness to these players that went beyond physical bravery on the football field. Against all odds, both Arbanas and Budde continued their careers and flourished.

The team had another disappointing season in 1964, going 7-7, while season ticket sales declined further.

The fans that were there were attentive and involved, but not always optimistic. Stram came in for more than his share of second-guessing, as did the team’s right tackle, Dave Hill, who was singled out for heckling after a few ill-timed holding penalties.

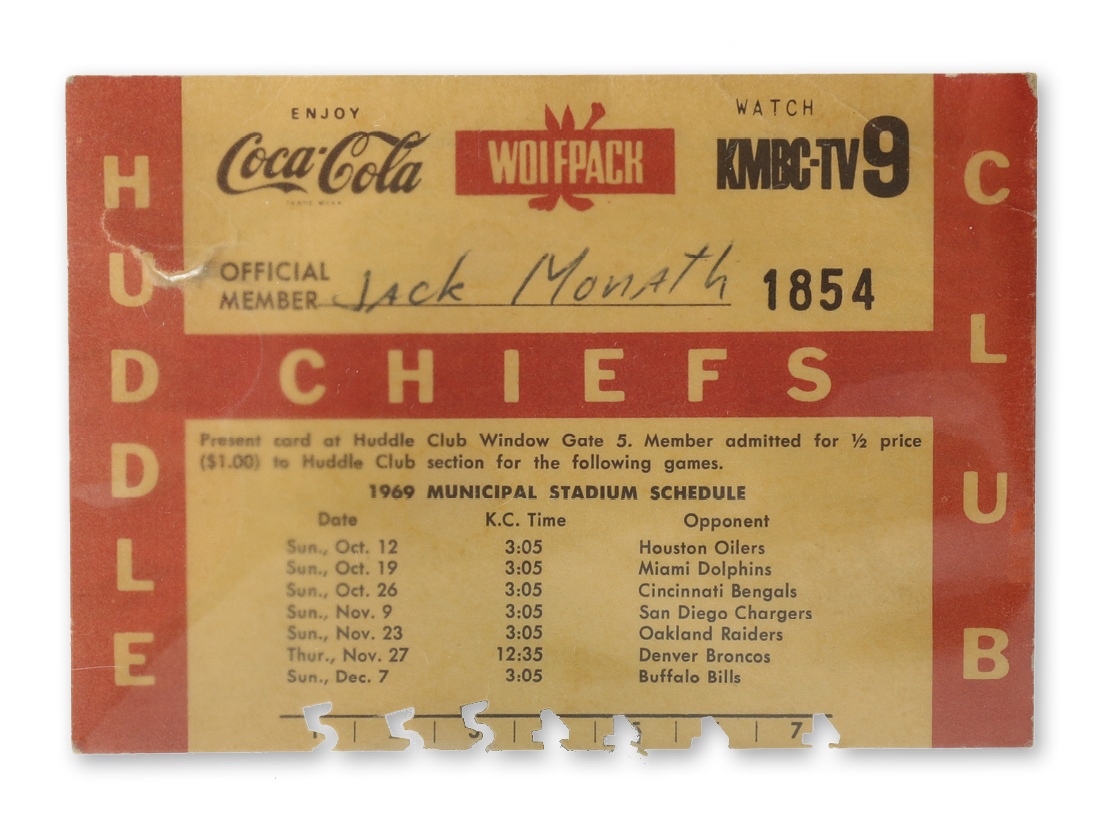

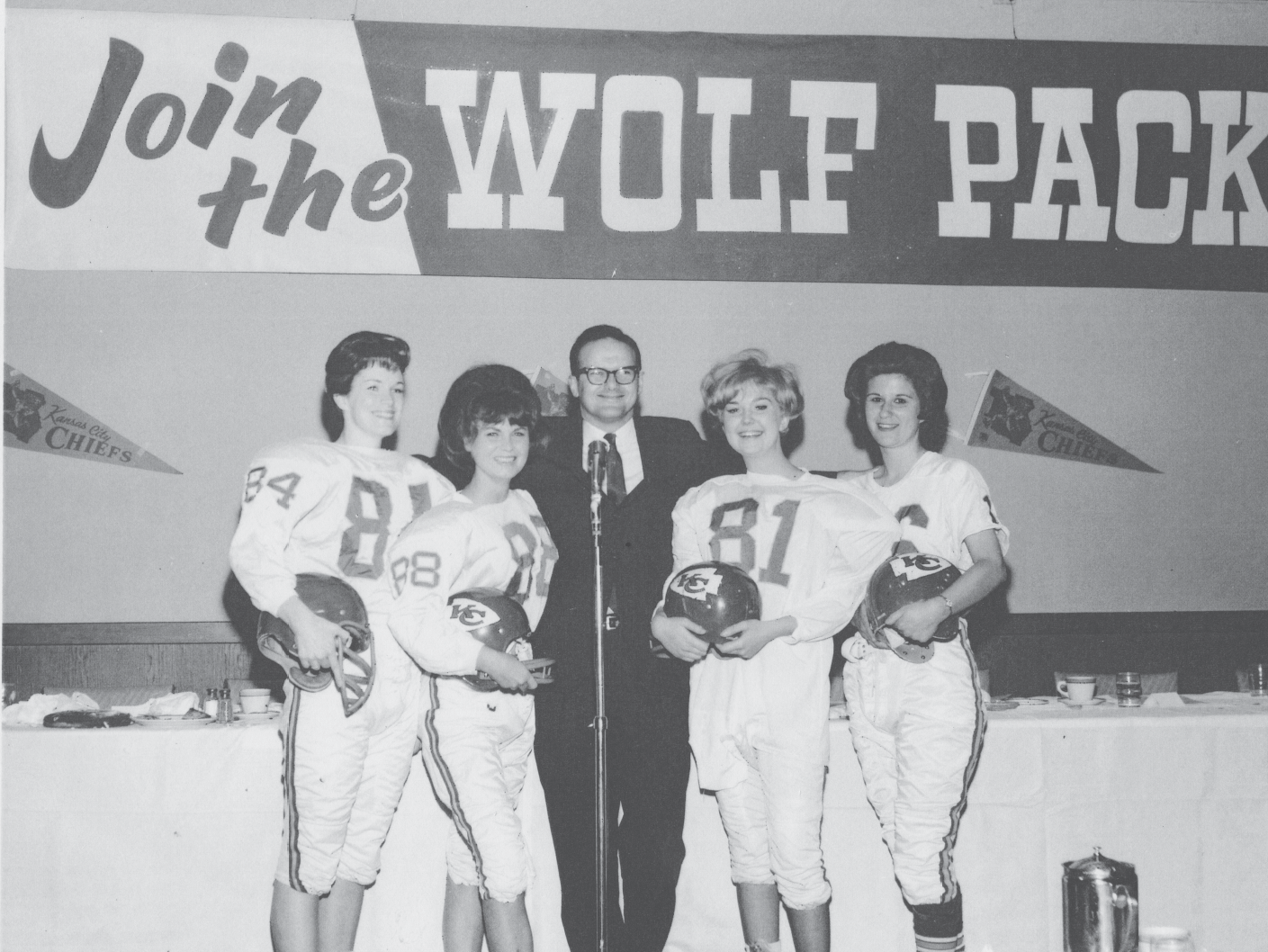

But by 1965, something was beginning to coalesce. The Chiefs were becoming a part of the city and vice versa. On November 30, 1965, the Kansas City Times ran an A-1 story titled “Wolves Wail as Chiefs Prevail,” on the clamorous crowd—dubbed the Wolfpack—sitting behind the benches in Municipal Stadium’s north grandstand. “Members are known for their football fervor and the acidity of their displays,” noted the story. Two weeks later, Hunt approved a marketing slogan for the upcoming season ticket campaign called “Join the Wolfpack.”

The 1965 season was a wildly uneven 7-5-2 exercise in inconsistency, enlivened by a rousing home win over the AFL West champion Chargers and another standout performance by fan favorite Mack Lee Hill, the second-year running back who gained 628 yards rushing before suffering a knee injury in the next-to-last game, December 12 at Buffalo. Two days later, during routine surgery to repair ligaments, Hill’s temperature spiked and he died of a massive embolism. In the days that followed, Kansas City came together, grieving Hill’s death and rallying around the Chiefs. “As terrible as it was, I think it established a bond between Kansas City and the Chiefs,” said Hunt. “Things really began to change soon after.”

With Finley’s Athletics eyeing a move, and rumors circulating that the Chiefs were being wooed by other cities, Hunt wanted to make a point. The Dallas native (who had never lived anywhere else as an adult) moved to Kansas City for the winter and spring of 1966 with his wife Norma and their infant son Clark, renting an apartment on the Plaza. Lamar made the rounds to sell season tickets, attending Kiwanis Club and Jaycees’ luncheons, Shriners Club dinners and Boy Scout pack meetings. During the day, Norma walked Clark in a stroller around the Plaza’s Spanish architecture, statuary and fountains, acclimating to their new surroundings.

The “Join the Wolfpack” campaign was an instant hit, as the season ticket base grew from 9,559 to 21,949 in the space of a single off-season.

In that same off-season of 1966, a truce was announced between the National Football League and the American Football League. The leagues would begin playing an annual AFL-NFL World Championship game starting with the 1966 season and would merge fully into one 26-team league in 1970.

Hunt, who’d helped negotiate the agreement, was named a member of the AFL-NFL merger committee. On July 25, 1966, he sent a memo to NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle in which he suggested the two leagues come up with a distinctive name for the new title game. “If possible, I believe we should ‘coin a phrase’ for the Championship Game,” wrote Hunt. “I have kiddingly called it the ‘Super Bowl,’ which obviously can be improved upon.” Rozelle didn’t care for the name, but that soon became irrelevant. Though the NFL officially described the contest as the “AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” nearly everyone from media to fans to players had already adopted Hunt’s term.

The Chiefs, led by Dawson’s accurate passing and young stars Mike Garrett and Otis Taylor, won the AFL title in 1966, to qualify for the first Super Bowl. The initial on-field meeting between the Chiefs and the Green Bay Packers of the NFL was played under immense pressure, as both teams were defending the honor and legitimacy of their respective leagues. On January 15, 1967, in front of a far-from-sellout crowd at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the Chiefs’ greatest hopes seemed within their grasp at halftime, when they trailed Vince Lombardi’s Packers by only 14–10. But a key interception in the second half led to a quick Packers score, and the Chiefs left losers, 35–10.

Lombardi’s dismissal of the Chiefs after the game—“I think Kansas City is a top football team; it doesn’t compare to the teams in the National Football League”—stung Chiefs’ loyalists. After the game, walking off the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum field, Stram had been wounded but resolute. Falling in step with team scout Lloyd Wells, he vowed, “We’re going to come back, and we’re going to win one of these.”

The following season was a washout, with many key players injured, as the Chiefs saw their ascendant rivals, the Oakland Raiders, qualify for the second Super Bowl. Also in 1967, after 13 miserable years—each season a losing one—the Kansas City Athletics finally fulfilled Finley’s threat and left town, moving to Oakland. This gave the fans in Kansas City yet another reason to dislike the Raiders, not that they needed it.

In the 1968 season, in which Stram had rebuilt his team with eight new starters, the Chiefs registered a 12-2 record, only to end it with the desultory playoff loss in Oakland.

By 1969, season ticket sales rose to a new high of 42,000. The weekly Chiefs Club gatherings were so popular that they had to be split into two events—a luncheon downtown at the Advertising and Executive Sales Club, with Stram and a couple of players speaking, and a return engagement, with a more ecumenical audience, early Thursday evenings at the Seven Arches Room of the U-Smile Stadium Inn.

The lunch meetings featured an emcee, usually broadcaster Bill Grigsby, interviewing Stram, as well as Stram narrating the previous week’s game film. Next, players would be asked a few questions, and the public relations director for the next weekend’s opponent would talk about his team. But the main attraction of any Chiefs Club meeting was the public Q & A with the head coach, which at times took on the aspect of a public inquisition. The Kansas City Star began covering the luncheons as a sports news story. The same ethos that prevailed in the Wolfpack existed in the Chiefs Club. While the fans loved their Chiefs, they were quick to criticize.

After a narrow loss to the Chargers in ’68, a questioner at the luncheon asked why the Chiefs had repeatedly gone with Mike Garrett instead of the bigger, stronger Curtis McClinton down at the goal line. Stram curtly explained that since McClinton had been stopped earlier, he wanted to use his best runner (Garrett) carrying behind his best blocking back (McClinton).

“That’s no answer,” said the man.

Stram’s lips tightened and his brow furrowed. Crossing his arms, he commanded the questioner, “Stand up.”

When the man did, Stram said, “What business are you in?”

“I’m a lawyer.”

“Have you ever lost a case?”

“Yes.”

“Have you ever had 50,000 people second-guessing your loss?”

“No.”

“Well, then sit down and behave yourself.”

That response earned a cheer. While Stram disliked the criticism, he enjoyed the spontaneity and high-wire act of the jousting, and considered himself equal to the task. Occasionally, if things grew too heated, Grigsby would step in and say, “No more beers for the questioner.”

In the fall of 1969, the Kansas City Chiefs had found a home and had become a galvanizing, unifying presence in the city. Both the team and the city were eager to be viewed as major league and moving in a headlong rush toward modernity, style and a vision of success defined by more than the bottom line.

In speaking of his team at the beginning of the season, Stram said, “We are striving for complete balance and consistency, both artistically and mentally.”

At times like that, he could sound as much like an urban planner as a football coach.

Kansas City in the mid-’60s was a city striving for modernity and growth, eager to shed its “cowtown” stereotype.

Though the early target of 25,000 season tickets was not met, Hunt’s team moved to Kansas City in June 1963.

Hunt moved to Kansas City for a few months in the spring of 1966, to help the Chiefs’ “Join the Wolfpack” season ticket drive, which more than doubled season ticket sales.