As the parade wound its way through the ticker-tape blizzard on the streets of Kansas City that chilly Monday morning in January 1970, the future looked incredibly bright for the Kansas City Chiefs.

They had, at the time, eight future Hall of Famers on their roster, another coaching on the sideline, and yet another as the franchise’s founder. They, along with the Green Bay Packers, were the only teams to appear twice in the first four Super Bowl games, and their innovation was already re-shaping the game.

Teams followed the Chiefs’ lead by adding more size to their offensive line and more speed to their secondary. The odd-man fronts the Chiefs used in Super Bowl IV would soon become popular, leading many teams to adopt a base 3-4 defense by the end of the ’70s. The signing of Stenerud—and later Bobby Howfield and Horst Muhlmann—foreshadowed the influx of soccer-style kickers into the game. The myriad intricacies of Stram’s multiple offense, including a penchant for presnap shifts and men in motion at the snap that could cause momentary hesitation in the defense, would be widely imitated in the decades to follow.

The Chiefs’ influence could already be seen in scouting, where their enthusiastic embrace of players from predominantly black colleges would be imitated most closely by the Pittsburgh Steelers. Pittsburgh had hired the savvy Bill Nunn; like Wells, he was a journalist-turned-scout with deep connections among historically black colleges and universities. The Steelers dynasty of the ’70s was built on a foundation of such players, and soon more teams followed suit.

For the Chiefs, the future seemed rich with possibility. “They never thought that was the only Super Bowl they were ever going to win,” said Cheryl Anderson, Otis Taylor’s first wife. “They thought it was the first of many.”

•

There was a feeling on the day of the parade that Kansas City had finally arrived, and all that was modern and innovative, and true about the city, was reflected in this team.

With the victory as the catalyst, many in the city seemed ready to put the darkest parts of Kansas City’s history—the mafia presence, the memories of the Pendergast Machine, and the dubious civil rights record—behind them. The celebration was underway, and in Kansas City, it went on for a while.

At halftime of the Super Bowl, shortly after Garrett’s touchdown, local musician Bill Roberts, who played a steady gig at The Seven Arches (the lounge where the Chiefs Club dinners were held every Thursday night), was inspired to write a song about the Chiefs. By the evening, he had recorded a scratch demo on cassette, played it for a friend, and dropped it off with Phil Jay, the evening DJ on WHB, the city’s leading Top 40 station. Jay played the song, and before the night was out, the station had received hundreds of requests to hear it again.

Roberts went into the studio a few days later with a rock and R&B combo called The Fab Four and recorded the single “Kansas City Chiefs,” which grafted new lyrics onto the melody of Leiber & Stoller’s “Kansas City.” In the space of two minutes and ten seconds, the song managed to poke fun at the NFL (“Vikings favored thirteen points/Were short by twenty-nine”), highlight the game’s key points (“Stenerud and Garrett’s points made the grandstand shake/ Taylor took it home to put the icing on the cake”), and even had a verse reciting the entire forty-man roster:

Dawson Lynch Garrett Flores Pitts McVea and Hayes

Lothamer Taylor Tyrer Buchanan Brown Lanier and Mays

Livingston Holmes Culp Prudhomme Mitchell Stein and Belser

Podolak Budde Moorman Trosch Holub Bell and Sellers

Arbanas Marsalis McClinton Daney Wilson and Stenerud

Kearney Hurston Thomas Richardson Hill and Robinson, too!

The recording was infused throughout by a fraternity rock feel and accompanied by laughter and what sounded like glasses clinking in festive toasts, as the group closed in unison with “God bless you, Kansas City Chiefs!” It was in the stores by the following week and became a minor radio hit in Kansas City.

They weren’t the only ones singing the praises of the Kansas City Chiefs. The day after the parade, Stram and Dawson traveled to New York to appear on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, and later that week were guests on The David Frost Show (along with Federico Fellini and Sid Caesar).

Over the next few weeks, Stram traveled the awards-banquet circuit. In February, he was honored by the Washington Touchdown Club. Stram was introduced by Vince Lombardi, who’d just completed his first year of coaching the Redskins (and would be dead of cancer within seven months). “I’ve seen a number of good football teams over the years,” said Lombardi. “But I don’t know when I’ve seen a team that was better prepared—physically, mentally, emotionally—as the Kansas City Chiefs were that Sunday afternoon in New Orleans against Minnesota.”

But the big moment, for the team and for their coach, was when the NFL Films production of the Super Bowl IV highlight film premiered in downtown Kansas City at the 700-seat Capri Theater on May 12, 1970. Suddenly, all the players understood why Stram had been so animated on the sidelines at Super Bowl IV. On the eve of the game, he’d agreed with NFL Films’ Ed Sabol to wear a hidden microphone for the Super Bowl. In what would become the most popular of all the NFL Films’ Super Bowl highlight films, Stram was the focal point of the entire film.

“Let’s matriculate that ball down the field, boys.”

“They can’t stop that in a million years!”

“65 Toss Power Trap!”

“You marked it good!”

Throughout the film, the audience in the theater roared with laughter, sometimes drowning out Stram’s subsequent lines. At that point, they didn’t realize those phrases would go into the canon of football lexicon; they only knew it made for great theater and great television.

It was a good time to be Hank Stram.

•

In June, a month before the 1970 training camp began, the rings arrived by mail at each of the players’ homes. They were presented in wooden gift boxes with matching cuff links and tie-tack inside. A gold-plated inscription on the top of the box read:

KANSAS CITY CHIEFS

WORLD CHAMPIONS, 1969

REMEMBER THAT YOU ARE WORLD CHAMPIONS

HANDLE YOURSELF WITH CLASS AND STYLE,

GRACE AND DIGNITY

—— [Signed] Hank Stram HEAD COACH

The ring featured ten quarter-carat chips (signifying the ten years of the AFL) in the shape of a football, surrounding a one-carat diamond in the center. For some players, the ring symbolized everything they’d worked most of their lives to attain. Ed Budde wore his every day, as a symbol of the culmination of all his work, sweat, and blood.

For others, the meaning was more practical.

“I got a ring on my finger that was the greatest barroom conversation piece for meeting girls you could ever imagine,” said Bob Stein.

The fall of 1970 brought a flood of media on the Chiefs. The Star’s longtime sports columnist, Joe McGuff, wrote an intricate, authoritative history of the franchise called Winning It All: The Chiefs of the AFL. Dawson wrote a book with Lou Sahadi, the editor of Pro Quarterback magazine, called Len Dawson: Pressure Quarterback. Another writer, Larry Bortstein, wrote a book about Dawson, Len Dawson: Superbowl [sic] Quarterback. A photo of Stenerud kicking in Super Bowl IV graced the cover of The Pro Season, a chronicle of the 1969 season written by Tex Maule, the lead football writer for Sports Illustrated. And Buck Buchanan and Curley Culp, shown chasing down a beleaguered Joe Kapp, were on the cover of The Other League, a stylish coffee-table book chronicling the ten-year history of the AFL.

Dawson was on the cover of more than a dozen preseason annual magazines that fall, and he was card No. 1 in the 1970 Topp’s Pro Football card set. Stram was featured in Sports Illustrated’s pro football preview issue and signed an endorsement deal with Gatorade.

When ABC debuted its Monday Night Football telecast in September 1970, the opening montage featured football action scenes rendered in colored scoreboard lights. Robert Holmes in action, barreling through tacklers, was prominently featured in the segment’s opening and closing.

•

Even then, and for years after, there remained a decided singularity to the Chiefs’ accomplishment. There was so much about it that was unprecedented or unique. It wasn’t merely that they were the first team in pro football with a majority of starters who were African American, or that they had the first African American middle linebacker calling plays on the field. It wasn’t just that they had the first full-time African American scout on the sidelines, or that one-third of the starting lineup was comprised of players from historically black colleges and universities.

The Chiefs emerged from a playoff format that was used in one league only, for just one year. They were the first team to win a pro football championship without winning a regular-season division title. They also weren’t technically a “wild-card team,” because that term didn’t come into widespread usage until a year later when the merged and realigned NFL had four playoff teams in each three-division conference. (The “wild-card” playoff qualifier was the non-division winner with the best record.)

In Super Bowl IV, at the conclusion of a season in which each of the NFL’s sixteen teams wore NFL 50 shoulder patches commemorating the league’s fiftieth anniversary in every game they played, the Chiefs were the only team to wear the patch commemorating the AFL’s tenth anniversary, and they wore it for just that single game. They were the first team to run a play out of the shotgun formation in a Super Bowl, and Stenerud was the first soccer-style kicker to appear in a Super Bowl.

Stram, in becoming the first person—either player or coach—to be wired for sound in a Super Bowl, left his own distinctive mark. And the game was played on the dividing line between two distinct eras in pro football, as the American Football League was ending, but in the last instant before the full merger between the leagues.

Then there was that singular, extraordinary defense. In the final two postseason games, they held the two highest-scoring teams in pro football to a touchdown each. Hall of Famer Joe Greene had just finished his rookie year with the Pittsburgh Steelers and went to New Orleans to watch Super Bowl IV. “I thought Kansas City would win that ball game because of their defense,” he said. “That was the first great defense. We tried to emulate the Chiefs.”

It would take nearly fifty years, but in February of 2019, Johnny Robinson was finally elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. And with that, the Chiefs defense of 1969 became the only defensive unit in pro football history in which more than half of the starters would be inducted into the Hall in Canton, Ohio. Buchanan and Culp, Lanier and Bell, Thomas and Robinson, all enshrined, all in gold jackets. No other defense in pro football history had six starters who played together at the same time.

So it was fair to ask why the ’69 Chiefs weren’t mentioned more often when people discussed the NFL’s greatest teams. An answer of sorts might have been offered in the episode about the 1975 Pittsburgh Steelers, from the NFL Films America’s Game documentary series. The film focused on the Steelers’ season defending their first world championship, and opened with defensive end Dwight White saying, “There are two categories of Super Bowl participants that nobody remembers: One, the team that lost the game; and two, the team that only won one.”

At some level, there was an irrefutable logic to White’s statement. In the collective memory, the Chiefs of 1969 were squeezed out by dynasties on either side—the Packers of the ’60s, and the Dolphins and the Steelers of the ’70s. For this team, there would be just the one title, the one ring, the one parade.

This was a fact about which Warren McVea, for one, was still bitter. “That team,” he said, “should have won three or four Super Bowls.”

The Chiefs had the opportunity, but in trying to defend their title in 1970, they were formidable but inconsistent. They lost the rematch to the Vikings in the season opener at Minnesota, then utterly destroyed the eventual Super Bowl champion Baltimore Colts a week later on Monday Night Football. Though ten Chiefs would be named to the Pro Bowl squad that year, they missed the playoffs, finishing 7-5-2. The season would be remembered largely for the bench-clearing melee between the Chiefs and Raiders, prompted by Oakland’s Ben Davidson spearing Len Dawson, and Otis Taylor racing to Dawson’s defense. (The offsetting penalties came after Dawson’s apparent game-clinching first-down run, and cost them the victory, as the Raiders rallied for a galling 17–17 tie.)

A year later, in 1971, the Chiefs had perhaps their best team ever. In their final season playing at Municipal Stadium, they beat the Raiders in a key late-season game at home to win the AFC West. Then came the AFC Divisional Playoff on Christmas Day in Kansas City, as the Chiefs and Miami Dolphins waged their six-period epic, the Longest Game Ever Played, with Miami ultimately prevailing 27–24.

That loss most likely kept the Chiefs from a third Super Bowl appearance in the first six years of the game. It probably delayed Hank Stram’s Hall of Fame induction by two decades and seems likely to have kept Otis Taylor (who’d won the AFC Offensive Player of the Year Award for his dominating season in ’71) out of the Hall of Fame altogether. The Dolphins ended up going to three Super Bowls in a row and winning two. However, the great nucleus of the Chiefs team that walked off the field that Christmas Day in 1971 would never again reach the same heights.

The move to Arrowhead Stadium in 1972 only underscored the aging of the Chiefs’ key players and the passage of time. Buck Buchanan was never going to look right playing on artificial turf; Len Dawson wasn’t meant to wear the Stram-designed shiny red game shoes.

In ’74, after a 5-9 season, the team’s first losing record in 11 years, Hunt called his old friend Stram and gave him the news. “Oh, lad,” he said, “This is a very sad day in the history of the Kansas City Chiefs. I’ve decided to make a coaching change.” Suddenly, the only head coach the Chiefs had ever known was gone.

Robinson, Holub, and Mays had already retired by then, with Bell, Tyrer, and Hayes following at the end of that season. Dawson, Buchanan, and Taylor finished their playing careers after the 1975 season, and Budde after ’76. The roommates Lynch and Lanier went out together after 1977. There would be no more choir huddles, no more tailored suits for road games. The Stram Era had ended.

•

Finishing a career with a single Super Bowl championship is hardly a tragedy. But some of the things that happened afterward were.

On September 15, 1980, six years after retiring, despairing of his perceived options, Jim Tyrer shot and killed his wife in her sleep, then killed himself.

His behavior was completely inexplicable at the time, but in the coming decades it would become clearer. Tyrer behaved with the same sort of irrational irritability as players who, generations later, would be diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. “All of us were scratching our heads and saying, ‘Why didn’t we know?,’” said Jack Rudnay.

The answer was simply that, at the time, nobody knew. In the future, there would be a better understanding of, and more psychological support for, players transitioning out of their playing careers. There would be a greater awareness of how repeated concussions and head trauma could turn kind and gregarious men mean and mad.

Tyrer’s death was part of a long litany that befell that ’69 team. Two years earlier, Len Dawson’s wife, Jackie, died of cancer, with more to follow: Cancer took Buck Buchanan in 1992, Jerry Mays in 1994, and Jerrel Wilson in 2005.

George Daney died of carbon monoxide poisoning while working on a car in his garage in 1990. In 1997, Aaron Brown’s van broke down on the way to a party with his wife, Reatha. When he got out to walk back to his home, he was struck by a motorist and killed.

Despite all of these tragedies, many of the players remained close through the years. They moved through the next chapters of their lives still incredibly proud of what they had accomplished. Many were careful, however, to not let the rest of their lives be defined by it.

“When I left the game, I was done,” was how Jim Lynch put it. At the Fortune 500 company where Goldie Sellers worked, his boss asked him if he would wear his Super Bowl ring every day, but Sellers politely declined. “I didn’t want people to see me just as a football player.”

They were a lot more than just football players. Johnny Robinson took over a boys’ home in Louisiana. Curley Culp went back for his graduate degree. Fred Arbanas served for decades on the Jackson County Legislature. Curtis McClinton was a professor in college and for a time served as the deputy mayor of the District of Columbia. Lanier, Lynch, Buchanan, and many others found success in business.

But what they never found again was what they had in 1969: During that season, they were the very ideal of what a team should be, a whole that far exceeded the sum of its parts, a collaboration built on mutual commitment and trust. It was difficult to replicate.

“Since I left sport, I have not seen anything close to a team,” said Willie Lanier in 2003. “I’ve heard people in every organization speak about ‘team-building,’ trying to have that thing called a team. I have not seen it come close. Because the concept is not words, it’s people. Having a heart and a feeling for one another that extends beneath the core to what someone else says. So if you don’t have that in essence, you can use the words, but you don’t quite have the thing.”

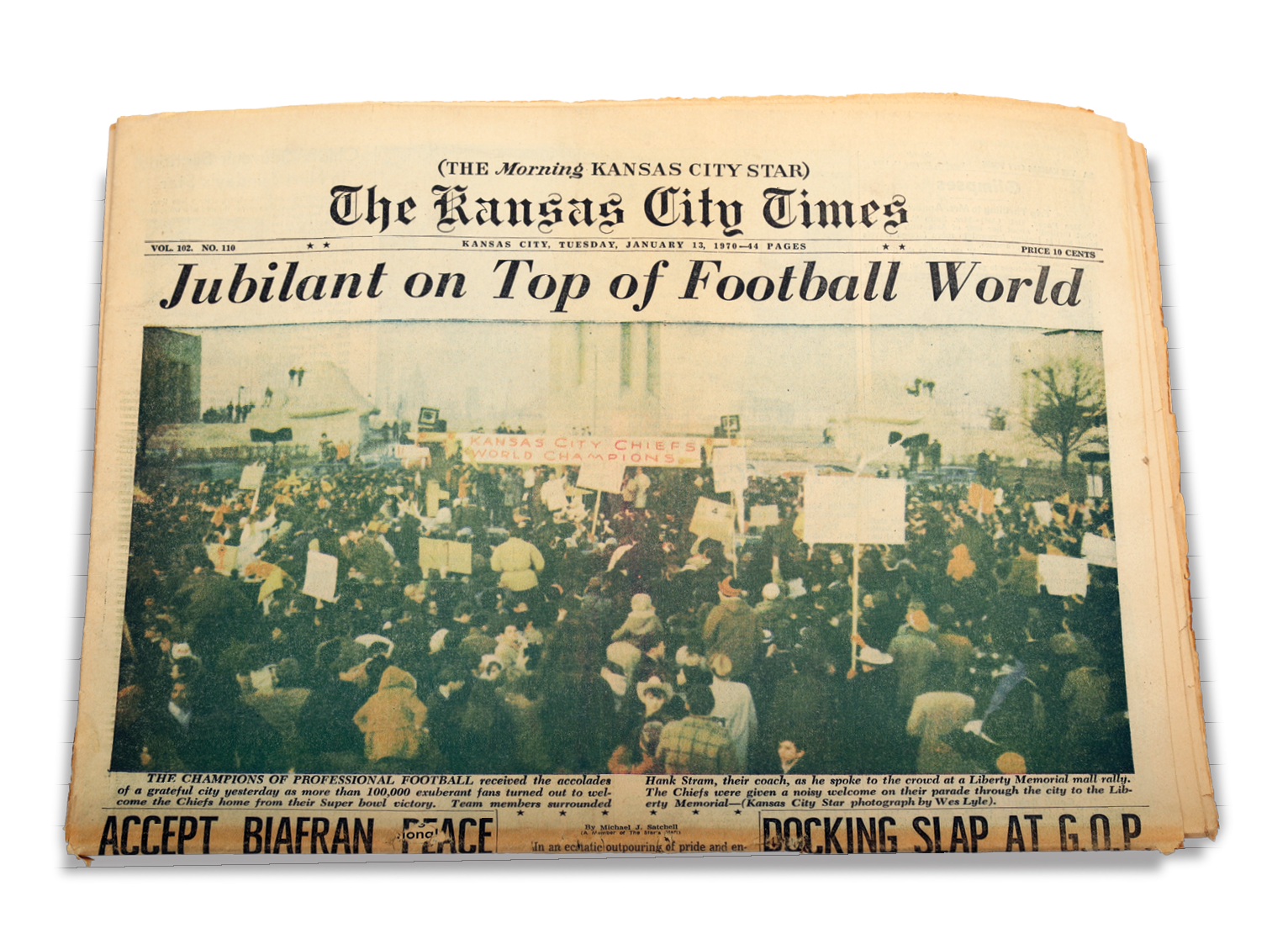

A crowd estimated at 150,000 turned out to honor the Chiefs.

The celebration in Kansas City lasted for a while, and included the novelty single by Bill Roberts, and the world premiere of NFL Films’ Super Bowl highlight film.

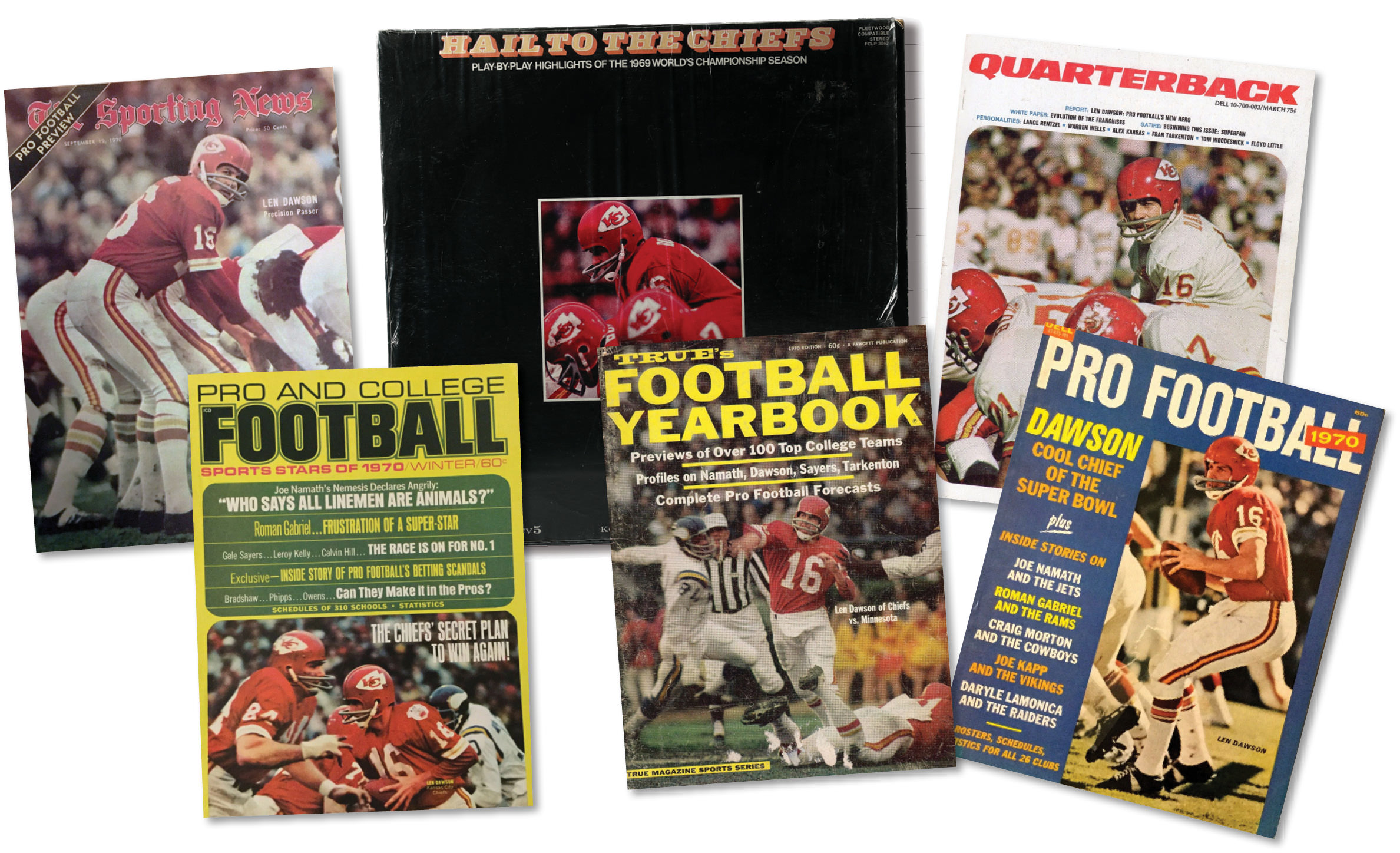

The fall after the Super Bowl win found Dawson on the cover of two books, a record album, and countless football magazines.

The Chiefs’ 1970 yearbook celebrated the title with a unique “keyhole” cover.