for ROBIN A. DUBNER

Attorney-at-law Saint-Germain's staunch defender

''.<' »•.;;.■.jfc Brainnabor

if'

THURINGIA

GERMANIA

FRANCONIA

:};:y?:/:.

ff

.::;.:>•..■•.-'.f.

TouJ

'"■'-•%

Ratisbon .••."•'."■'•':•.'

BAVARIA

*■•;'.■• V'-*i"."

/^^/ CkJ!f<jtJ^Ai/aiM<^

;*,;•> v.\>

t[££E:R ^^0i^S

SAXONY

Hamburh

Lauenburh

l^^l rlc

^JuaJUuxxM^^

BETTER

IN THE

DARK

Author's Notes

There is a reason they are called the Dark Ages, and not the least of it is that they are hard to identify; historians are divided in opinion as to when they begin and end. Most prefer to establish the onset of the Dark Ages at the fall of Rome, although that date, too, is open to debate, since it can be interpreted as:

a) the splitting of the Roman Empire under the sons of Constantine I, in 340 a.d.,

b) Alaric's sack of the city in 410 a.d.,

c) the German barbarian Odoacar's execution of the last Roman Emperor and his subsequent assumption of the title King of Italy in 476 a.d.,

d) the coronation of Clovis I, who defeated the Roman Governor of Gaul to become the first King of France in 486

A.D.,

e) Totilia the Ostrogoth's triumph over and expulsion of the Byzantines from Italy in 540 a.d.,

f) and so on.

For convenience, I put the beginning of the Dark Ages around 500 A.D.; the end came roughly between 1130 and 1220 a.d., depending on what part of Europe is in question, for these changes happened slowly, and their effect took time to be felt. At this period, a regional lag of a century or more was not unusual. Architecturally the Dark Ages are often called the Romanesque and come before the great changes of the style called Gothic, heralding the beginning of the Medieval period.

Architectural styles, as all things in human culture, do not exist in a vacuum; the gradual development in building mirrored many other social developments. Too often it is generally assumed that European societies went from Imperial Roman to Medieval in a flash consisting primarily of King Arthur, Vikings, and Charlemagne, forgetting that the flash lasted nearly seven hundred years, years that also embraced.

to touch on a few highlights—along with King Arthur, Vikings, and Charlemagne: the Byzantine Emperor Justinian and his wife. Empress Theodora; the life of Saint Benedict, who established the Rule of monastic hfe that is still followed today; the rise and fall of the Lombards in northern Italy; the rise and fall of the Visigoths in Spain; the halt of barbarian invasions in Europe; the rise and fall of Persian dominance in the Middle East; the hfe of Mohammed and subsequent rise of Islam in the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and Spain, as well as the attempted expansion into France and the Mediterranean islands; the work of the Enghsh monk-historian the Venerable Bede; Saint Boniface and his attacks on German paganism; the establishment of Ambrosian and Gregorian chants in European Christian churches; the colonization of England by Vikings, Angles, Jutes, and Saxons; the life of Alfred the Great; the establishment of Novgorod and the conquest of Kiev by the Viking Rurik and the resultant founding of the Russian state; the arrival of the Magyars in Hungary: the plays of Hroswitha of Gander-sheim; the founding of the Holy Roman Empire: the first official canonization of Christian saints; the writing of Beowulf; the reigns of Ethelred I the Unready and Canute in England and Denmark; Robert II of France and the institution of'The Peace of God"; the life of Ruy Gomez y Diaz de Bibar, called El Cid; the Norman conquest of Sicily and southern Italy and the subsequent massacre known as ''Sicilian Vespers"; Macbeth's reign in Scotland; the Norman conquest of England; the First Crusade; the establishment of the Republic of Florence; the lives of Peter Abelard and his mistress/wife/student Heloise: the rise of the troubadours. Minnesingers and Meistersingers; and the Stephen-Mathilda war in England.

Hard as it may be to identify the beginning and end of the Dark Ages, the years 937-940 a.d. are clearly smack in the middle of them, and demonstrably not part of Medieval culture. The language is markedly diff'erent than that spoken anywhere in Europe today, just as modern English is not very much like Old or Middle English. Because of language "drift," names that are common to us look strange in their earlier forms: Giselberht instead of Gilbert, Walderih for Walter, Cul-fre for Colin, Ewarht for Everett, Rupoerht for Robert; a few, like Karagern and Ranegonda, are no longer popular and have disappeared. Place names, too, have altered. For example, in 940 a.d. Lorraine is not yet Lorraine: it is Lortharia or Lorraria, depending on which source is being used. And the countries are different shapes than the ones we know today—although the shapes have changed several times in the twentieth century and are continuing to mutate as I write this in 1992. The customs are not those of the great Medieval states, and

the conceptions originate in a different mind-set than the predominantly empirical one that was standard in Imperial Rome and is again in our time. This period produced an intensely subjective cosmology, laden with omens and symbols and codes. Although not caught up in the fatahsm of the doctrine of predestination, the people of the tenth century often saw themselves the target of a complex series of tests, with often their very survival depending on the successful completion of these enigmatic tests, or the correct interpretation of omens.

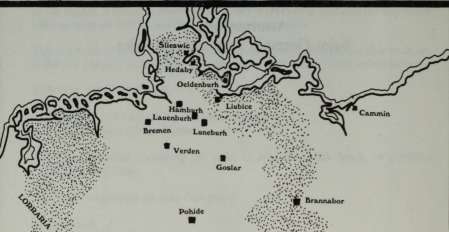

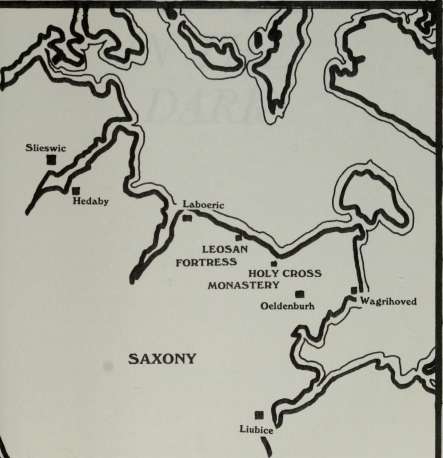

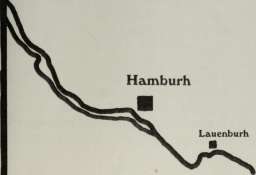

At the time of this novel. Saxony was in a more northern part of Germany than it is today; in the tenth century it occupied most of the southern end of the Danish peninsula and much of the territory south to the forests of Thuringia. On the west it bordered Lorraine and part of Burgundy; to the east, Warnabi, Nordmark, and Lusatia, roughly the same boundary as the recent border between East and West Germany. The north-eastern section of Saxony along the Baltic Sea had only recently been subdued; German-founded villages were isolated and had to be protected and self-sufficient to survive. The nearer the villages were to the newly estabhshed border with Denmark, the more hazardous the life there was: Danes often raided south for goods and slaves, and outlaw bands controlled large sections of the vast forests that covered most of the region.

In 937, the new King of Germany, Otto, later called the Great, undertook a lifelong and vigorous campaign to expand and unify the various German duchies and cities as well as to develop a German presence in the border areas of his Kingdom. He managed this so successfully that he conquered Italy as well as most of Germany and became the first Holy Roman Emperor. His reign is sometimes referred to by historians as the Ottonian Renaissance, but that seems going a little too far to me. Many of his achievements were the out-growth of earlier attempts to strengthen the German state, and his greatest attainments were mihtary, not academic or artistic. His father, Henry (or Heinrich or Haganrih) I, had annexed the Schleswig marches in 934. Or to put it more accurately, he took the land and kicked the Danes out. From that time on the German settlements in the region, once marginal at best, became strategically important, and as a result were subject to all the advantages of enhanced attention—more armed troops, regular inspections, reinforcements, preferment in allocation of supplies, an increased presence of the Christian church—as well as all the disadvantages—greater military risk, higher taxes, increased obligations to other Germans, an increased presence of the Christian church.

While the fortress and its inhabitants in this story are fictional, they are in many ways representative of the various German coastal installa-

tions which were established along the Baltic Sea from about 890 to 1050 A.D. The monastery of the Holy Cross is also fictional, but based on accounts of such institutions at the time and in the general geographical region of the story. There are more historical ingredients in the tale: the outbreak of ergot in 936-940 is recorded from central Lorraine to Pomerania (northern Poland); the sack of Bremen by Magyars occurred in 938; the harbor city of Hedaby (or Haithebu or Heida-bai), slightly south of the modern city of Schleswig (Slieswic in 950) near the German-Danish border, was about the most important commercial port on that part of the Baltic coast—neither Keil nor Lubeck was in business yet, beyond local fishing, and were not known by the names they bear now; the institution of deputizing a female relative to serve for a male, while uncommon, was legal and did happen occasionally; there were Orders of monks who followed the Cassian Rule and chanted prayers around the clock in shifts called Choirs; paganism was still very powerful in northern Europe and the Christian church would need another two hundred years to finally get the upper hand; poor and unmaintained roads made travel arduous, while bandits, pirates, and local warlords made it extremely dangerous. Journeys overland usually moved in 15-20 mile-per-day increments in good weather, as little as five miles per day in bad weather. Voyages were equally chancy and were undertaken only by the hardiest and most determined, who were willing to assume tremendous risk for the possibility of tremendous profit. Most profitable of all was the spice trade, which included dyes and glazes; in Europe, ginger and pepper were especially prized, and the merchants who succeeded in delivering these were often set for life. These adventurous merchants also tended to be held for ransom if they were unfortunate enough to fall into the wrong hands. What laws there were in effect were often harsh and arbitrary, and the punishments attached to wrong-doing look excessive to our eyes. Few countries had a uniform code of laws, and those that did were subject to regional variation and the prejudices of the presiding official. In tenth-century Germany, or Germania as it was then, most of the regional government, such as it was, was under the direction of a Gerefa who had authority over a castle or fortress and as much of its immediate environs as could be policed. This title, while inheritable, was generally appointed; eventually it became GrafT, or Count in German and Sheriff" in English. The Gerefas were under the supervision of a Margerefa (or Meirgerefa), an administrative office determined by the King, usually awarded to relatives and powerful regional landholders. The office and the title eventually became Margrave. Technology was not very advanced, and many of the engineering

feats of the Imperial Romans were thought to be the work of magicians in the Dark Ages. Intellectual curiosity was not regarded as a virtue and occasionally resulted in persecution. Yet there were some developments, and a few rediscoveries that improved the lives of many of the people in the tenth century. Four innovations proved to have the greatest impact in the average person's life at about this time: the invention of the horse collar, which allowed oxen to be replaced by the stronger, faster horse as an agricultural animal; the three-field crop rotation system; the floating mill, built on rafts and rising and falling with the river so that grain could be ground year-round; the standardized horseshoe and horse-shoe nail, which proved to be of enormous military importance.

Provisions of all sorts were in chronically short supply, whether cloth or metal or rope was wanted, in large part because methods of production were inefficient and slow. Food and foodstuff's were not often plentiful, and nutrition was more a matter of getting enough to eat than maintaining a balanced diet. For all but the privileged it was a fat-deficient diet, which led to less physical growth in youth as well as to a reduced birth rate because of the difficulty of carrying a pregnancy to full term. Life spans were short and infant mortality high, and although this story predates the arrival of Bubonic Plague in Europe by a few centuries, epidemics of several sorts regularly claimed many fives, for medical treatment was primitive at best; in some instances it was worse than the illnesses it purported to treat. A stonemason who lived to age forty with all his limbs intact could count himself lucky—if he made fifty, he was considered remarkable.

The center of the European world in the Dark Ages was Constantinople. The Greek-speaking Christian state there dominated the western world for about eight hundred years. From the faU of Rome, whichever date you choose for that event, to the founding of the Holy Roman Empire there was no rival of Byzantine power in Europe.

There are, of course, some thank-yous to add, along with the assurance that any errors in fact or historicity are mine and not made by these helpful people: as always, thanks to Dave Nee for yet another tremendous bibliography, this time of tenth-century material, as well as musical references for that period; to William Brown and Paul Howard for pointers on European language development and literacy in the tenth century; to Doris Weiner for access to her vast cofiection of European pagan anthropology; to G. G. Gerhart for advice regarding historical maps; to Paula Hill for her knowledge of Dark Age cottage industries and general domestic history; to Edward Smith, S. J., for information

on the state of Christianity in tenth-century Germany; and to my editor, Beth Meacham, and the rest of the Tor staff for their continuing interest in things that go chomp in the night.

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Berkeley, California

I

PARTI

Ranegonda of Leosan Fortress

JL ext of a dispatch carried by a messenger of the Holy See to the King of Germania, Otto. Dehvered June 28, 937.

To our most puissant ally and worthy ruler of the Germanian people, our Kiss of Peace upon the first anniversary of your reign for which we in Rome have cause to be grateful to Heaven in this 937th Year of Grace:

Too long have we seen the world torn by envious strife that can only find condemnation in the sight of God. We have seen the struggles of the people given little or no heed while the great concern themselves with the honor of killing. We must ask that such battles be directed in the cause of our faith, and that the long tradition of revenge which has brought a never-ending cycle of destruction be abandoned as unsuitable to Christians.

Your father most valiantly brought many pagan souls to God as he fortified his realm, and this is most worthy and favored by Heaven. We are informed that you have elected to continue this vigorous pursuit, and we are willing to endorse your expansions, but only as long as you are bringing grace and the true God to those people still worshiping idols and carrying on practices that Christians cannot name. It is fitting that a Christian King use his might to the glory of God and the advancement of the Church. We will praise all advances you make over heathen people.

We say this in the full realization that the codes of fighting men do not lend themselves to the ways of peace, but the day is coming swiftly when Christ will come again to judge the living and the dead. Surely the ferocity of the Magyars is only a foretaste, a timely warning that many of us will stand living at the Throne of God, and at that time none of us will wish to have the sin of murder or other treachery on his soul. We would be lax in our duty if we did not seek to end all earthly strife, and bring all souls to the Mercy Seat, for the battle for the souls of men must be won in the

cause of Christ if we are to sing with the blessed and fly with the angels around the Trinity in Heaven.

While we are aware that there are many dangers impinging upon you, we must ask that you bring nothing to your reign that would prolong the deprivations of war. It is one thing to repel the invaders from the Hungarian plains or force back the pagans in the forests, but it is another to drag your brother Christian into endless battles over the Lorrarian territories of what was so recently Austrasia. It would better serve your purposes for Germania and Francia to be resolved in your minds to end this dispute, for Lorraria is not worth the damnation of your souls and the ruin of your Kingdom. An alliance made by you with Francia would be most welcome to us, and to the Christian people of the world God has entrusted to us until His Son comes again to rule.

Content yourself with turning the Magyars from your land and extending your borders into the regions of the pagans: do not waste your men and your arms in strife with your Christian neighbors. Settle the dispute of the Lorrarian territories before you have depleted your land and are unable to withstand, let alone push back, the assaults of the heathen warriors from the East. The conversion of pagans is always pleasing in the Sight of God, but oppression of fellow-Christians is forever a sin. We make this demand of you as Christ's messenger on earth, and pray hourly that you will turn from your disastrous course and once again rule as the great King you are destined to be as the Last Days come upon us.

We wish you to recall that God is a righteous judge and that no secrets are kept from Him, Who commands the course of the stars and the rising of the seas. Bear in mind that you may escape the wiles of your enemies on earth, but no man is the least part of the majesty of God. Therefore let us hear swiftly of your intention to put an end to your rivalry with Francia. We will dispatch our own Bishops and Archbishops to you to negotiate the agreement if you do not have men of your own you wish to entrust with such a task. For those peoples beyond your borders who are not yet children of Christ, we pray that you will bring them the Light of the World

You are mandated by God Himself to show Christian charity to all those who have suffered at the hands of the marauders from the East. Let no door be closed against those who come for protection and comfort. As it befits a vassal of the King to honor his edicts, so it is fitting for Christian to receive Christian in the name of Him Who died for your sins. We admonish you to conduct yourself with proper humbleness of spirit. We want to hear nothing of peasants abandoned or villagers left to wander and starve. We do not wish to learn that the daughters of such parents have been sent into concubinage, or that their infants have been left alone

in the forests. Moreover, we do not want to hear that you have permitted their children to be sold to the heathens in the north as slaves, as has, lamentably, been tolerated in times past. Slavery is misfortune enough for those born to it, but for a Christian to be a slave to a pagan is abominable. Also we abhor those who treat with thieves and robbers to steal from those fleeing destruction, and we utterly condemn the reeves, comites, and captains who participate in this practice. We instruct all Christian leaders to punish any of their vassals who so abuse their Christian dependents. We order you and all your vassals to preserve the lives of Christian travelers in these difficult days. If you must have ransom, then so be it, but we will excommunicate any who indulge in slaughter. There are those who will not wish to do these things we require, but they are the ones who will howl in Hell when Christ comes to raise the living and the dead, and all things will be known to Him.

In the fervent belief that God will guide you aright and that Christ will favor you in your magnanimity, I embrace you as the hope of Europe, and sign with the Seal of the Fisherman, on this first day of Lent,

Leo VH

In the smaller of the two graves lay the swaddled bodies of three children, none of them older than five; in the other, set apart from the rest of the little churchyard, the body of their mother sprawled in the sodden garments she wore when they drowned her that morning. A restless, biting wind blew off the sea and scattered sandy earth onto her wet hair.

"A pity," said one of the monks at the side of the grave as he looked down at the mother.

"She was an adulteress," said his superior. Brother Haganrih, in a quelling tone. "She died as she deserved to die."

"It is still a pity," said the first monk. He was taller, younger than his superior, and in spite of his recent vocation he had not rid himself of his attitude of command, a fault for which he was often chastised and which he prayed daily to be rid of. He could not easily bow his head even now.

"She should not have done the sin. That is the pity, that she was weak," said the superior. "She let another man than her husband touch her."

The first monk sighed. "She said she was forced."

"What woman does not say that when she has been found out? It is the way of women to he, especially about their fleshly passions. Eve said a similar thing to Adam and to God, that the Serpent forced her to eat of the apple, not that she wished to have forbidden knowledge. Women are ever thus." The superior stared into the grave once more. "Best to cover her up. There's nothing more we can do for her in this world."

The first monk Signed himself and reached for the wooden shovel. "May the White Christ have mercy on her and upon all Christian souls," he said as he began to fill in the grave.

"The father will have to pay for killing the children," the superior reminded the first monk. "He will have to give forty pieces of gold."

The first monk nodded as he worked: Brother Giselberht was aware of the law of King Otto; it was not so long ago that he would have been the one to enforce it. He could not deny the justice of the sentence on the woman or the wergeld for the children. Still, as a man who had killed his first wife, he had the uncomfortable knowledge that such acts hngered and ate at the soul. He added his own petition to Heaven along with prayers for the repose of the dead woman and her children.

By the time he was finished, the wind had become fiercer; the sea was now a deep grey-green, rolling heavily like entwined sleeping monsters, whitecaps showing as far as the monk could see. Somewhere, beyond the horizon, a storm was gathering, the first gale of winter, he suspected, and coming almost a month earlier than usual. All the signs warned of hard times ahead: at dawn he had observed a fox-cub attacked and carried off'by an owl as night came to an end. It was an evil omen, one he had pondered through his recitation of morning psalms. He took his shovel and started along the low headland toward the squat wooden buildings surrounded by a stout log fence that housed the Aceomataec or Cassian Benedictines and was dedicated to the Holy Cross.

This place was not so much a change from the fortress Brother Giselberht had commanded two years ago as it first appeared: both were isolated, both were less than sixty years old, and both had been established when the Danes had been pushed back and the Wagrians and Obodrites had been brought under the rule of the King of Ger-mania. Life in one was hardly less austere than life in the other.

In the monastery church the None Choir was chanting their prayers, part of the continual song of worship that rose from this place without ceasing. The monk stopped long enough to kneel at the entrance and prayed to be worthy to enter this holy ground. He was still new enough to the Order that he said none of his prayers by rote, but invested each

with emotion and fervor. As one of the Vigil Choir, he would enter the chapel to chant to the glory of the White Christ from the middle of the night until dawn.

Brother Giselberht returned the shovel to the tool shed and then made his way to his cell, one of four cubicles in a cabin of standing logs. There were seventeen such cabins, all in a row, and all but five of the seventy-three monks Hved in them: only the warder-Brothers stayed always in the gatehouse except during their Hours of chanting; Brother Haganrih had a cell at the rear of the church, where he could protect the altar with his hfe.

It was Brother Giselberht's hour of personal prayer, and he set about his devotions with the fervor and determination that were the mark of the depth of his conversion. He Signed himself, lay prostrate on the plank floor, and began to recite the Psalms, starting with the Sixty-first; Benedictine Rule required that he complete a recitation of the Psalms each month, but such was Brother Giselberht's dedication that he doubled the requirement regularly. Between each verse he asked God to forgive him for the murder of Iselda, reminding God and His Son that he had been in the right when he did it and that the reduction of the wergeld required by her family exonerated him from all wrongdoing. But these protestations brought him no peace and he felt as if his words were being drawn into a vast emptiness, which was a failure of faith.

When he left his cell he was exhausted, more ready for sleep than for the weaving he had been assigned to do. The bell for supper rang as he crossed the central court of the monastery, which aff'orded him some relief, although he longed for a slice of lamb or pork instead of the fish and bread and thick pea gruel that was their daily evening fare. Meat was one of the many things he had given up when he had renounced the world and his title. He lowered his eyes to the bare ground and noticed that a half-dozen dark feathers tipped with brilliant red were scudding along the ground, driven by the wind created by the hem of his habit as he passed. Another omen, he knew, but one that was mysterious to him. With the image of the feathers hot in his mind, he knelt at the door of the refectory and Signed himself, asking God to make him grateful for the food provided.

There were long plank tables set up along three of the four walls, and the monks gathering there did so in complete silence, taking their places and bowing their heads over the wooden platters set before them. Aside from the shuffling of their feet and the scrape of the benches the only sound in the refectory was the distant chanting of the None Choir.

Two of the new Brothers served the meal, offering bread trenchers to

each of the seated monks before putting the bowls of baked fish and pea-and-barley gruel on the long table. Large flagons of mead were put on each of the tables, and the monks filled their wooden cups with their contents. As soon as this was done, the two new Brothers prostrated themselves in the middle of the room and waited while the seated monks recited the prayers of thanksgiving. Then, as they returned to the kitchen to prepare a meal for the None Choir, Brother Haganrih came to the center of the room and began to read the Lesson for the day: the ordeal of Jonah in the whale. He was accorded the attention of every monk as the austere fare was eaten with as little attention to the food as possible in order to avoid the deadly sin of gluttony.

As soon as the Lesson was finished, the meal was over. Whether or not the monks had eaten their fill, or had tasted more than a sip of mead, they had no recourse but to rise and go to the ambulatory—in this case, a wide pathway around the inside of their walls—for meditation and preparation for Confession, which was carried on communally just before sunset, when the Compline Choir replaced the None Choir in their church.

Brother Giselberht was pondering the meaning of the omens of the day when Brother Olafr came hurrying toward him, swinging his crutch and hopping, making a signal to him to stop. The other monks in the ambulatory took great care not to listen to what passed between the two. ''Good Brother, may God keep you ever in His care," he said ritualistically.

"And amen say all good Christians," answered Brother Giselberht, but with reservation, for he did not often see a warder-Brother except to learn of misfortunes. "What has God brought to this place?"

"Your sister wishes to speak with you," said Brother Olafr.

"My sister?" he asked, because this was not time for her scheduled visit; he Signed himself, anticipating something terrible and hoping God would spare him in the same instant. "Did she tell you what the cause was?"

"She said only that it was urgent," replied Brother Olafr.

In a day beset with worrisome omens, this was the worst. "Where is she?" he asked, trying to do as the Order required him: to use as few words as possible.

"We have her at the gatehouse, in the reception room. She apologized for interrupting our Offices." Brother Olafr ducked his head, though his expression was more disapproving than humble, and he went on with resentment, "I did not look at her but to identify her."

"God will reward you for preserving your chastity," said Brother Giselberht distantly. "I will have to go to her."

"Brother Haganrih will not approve. You will have to Confess your disobedience." He frowned as he pulled his habit more closely around him, trying to keep out the freshening wind.

"I will do so," said Brother Giselberht, and started across the central court of the monastery toward the gate-house where visitors were received.

There was a single lamp in the gate-house reception room, and it was placed to illuminate a painting of the White Christ risen in glory; He was dressed in Byzantine splendor and the wounds in His hands and feet emitted rays of light. Smoke from the lamp was already fading the colors.

Ranegonda was wrapped in a long, hooded mantel dyed the color of pine needles that concealed her russet bliaut and pale blue chanise as well as her long, fair braids. She was kneeling before the painting, her head bowed, but rose as soon as her brother came into the room, her hand on the hilt of the dagger she wore at her waist. "God preserve you from all evil, Giselberht," she said, lifting the hem of her garments as high as her knees in recognition of his former status; her heuse were made of heavy leather with thick soles, and reached to her calves. She was much like her brother—slender, sinewy, tall, and grey-eyed—but at twenty-five she was showing the first signs of age that had not yet touched him.

"May the White Christ also keep you, Ranegonda," he said as he Signed himself, unwilling to look at her because he was embarrassed that she still insisted on treating him as if he commanded the nearby fortress. "It is not your day to be here."

"I know," she said, "and I apologize for intruding, but there are two circumstances that bring me." She watched him to see if he would permit her to continue. "First is that King Otto has sent word that he will not be able to supply the fortress with the requested additional soldiers until next spring. He has had other battles to fight and he cannot spare the men for a short while yet. I have the letter, if you want to read it?" She indicated the heavy leather wallet that hung from her belt along with a massive ring of keys.

"It is not fitting for me to read what the King has written; I am out of the world." He motioned her to move back from him, as if the very presence of the letter could contaminate him further. "You may tell me what it says if you think I must hear it, but otherwise, it is yours to deal with."

Ranegonda stepped away from him, limping a little, for her old injury was paining her today. "I will have to write to him, then. He will have to know that his dispatch has reached us and that the fortress is

taking measures to prepare for the winter without his assured help. Margerefa Oelrih will expect some account of our plans, and King Otto will demand an acknowledgment of his orders. But I will have to tell him that you have been informed or nothing I say will be heeded."

He nodded once, showing his understanding of her situation. "You have my permission to use my seal for this letter. You may write to the Margerefa and the King that you have informed me and that I continue to leave such concerns of the world in your hands. Say that I repose my trust in you, and beg that the King will do so as well." He waited for her to continue, and when she did not he reminded her, "You said there were two things."

"The second is the more difficult," she said, unwilling to look at him.

"Tell me what you believe I must know," he ordered her. "Since you are reluctant to speak of it, I must suppose it is about Pentacoste."

"I fear it is," said Ranegonda, her pale skin flushing.

"What is it this time?" Brother Giselberht asked, feeling very weary. He did not like having to turn his mind to his second wife, let alone talk about her.

"She has been permitting Margerefa Oelrih to visit her, as her own guest, not as the King's magistrate. He was at the fortress but two weeks since and stayed for ten days doing nothing but paying court to your wife. I have said that it compromises your honor and the honor of the family, but she says that there is no impropriety, and with you withdrawn from the world and your marriage to her, she is entitled to seek some consolation in the company of those whose rank is equal to her own. She has no desire to enter Orders and will not return to her father unless she is ordered by the King himself." She said this very quickly, as if she had been afraid that if she faltered she would not be able to finish. "I don't know what to do. She will not listen to my objections."

"No," said Brother Giselberht. "It is not surprising that she . . ."

"It makes no difference who speaks to her," Ranegonda went on. "She pays as little attention to Brother Erchboge as she does to me, and none at all to the other women of the fortress, not even her two attendants, who have been at pains to accompany her at all times." She looked away from him suddenly, her certainty fading. "She told Brother Erchboge that you deserted her for the White Christ, and that shows to her that the White Christ does not accept her, or He would have kept you together as man and wife."

Before he became a monk. Brother Giselberht might have thrown a tankard or a platter across the room had he been told of such intractability, had his wife dared to challenge him so flagrantly. Now he mas-

tered himself to click his tongue in condemnation. "It is pettiness and the frailty of women that makes her do this thing. As the master of the fortress in my stead, you may send Margerefa Oelrich away at any time he comes for business that is not the King's. Inform my wife that he is not to come again except in the discharge of his office. Tell her to pray for inspiration that she may be worthy to be one of those women who forsake their sex to leave the world behind for the glories of Heaven." He Signed himself and waited until Ranegonda had done the same.

When Ranegonda had Signed herself, she watched her brother with concern. "You're thinner," she said at last.

"It is fitting for a man with my sins to fast," he answered.

"Still," she said.

"I am grateful that God has given me time to seek redemption before ending my life. That it cost me a httle flesh is nothing if it preserve my soul." He was not quite three years her junior, and most of the time held her in affection. But there were times when she spoke as if they were still children and she tasked with guarding him at play or providing his meal for the afternoon, and such instances irked him.

"The signs are for an early winter, which could lead to a lean harvest; I know you have noticed them," she said. "I do not like to see anyone so thin when food is plentiful, for those are the ones who starve when food is scarce, as it is likely to be this winter. You will fast more than God could require before spring comes." It was a lesson they had heard from their mother all through their youth, before she had died ten years ago giving birth to dead twins in another hard winter.

"The White Christ provides for us here, Ranegonda," he reminded her sternly. "We are told to trust in Him."

Ranegonda gave him a somber look. "Your crops are like all the others, and they will yield less grain because of winter arriving early. The storms will destroy the crops, and there will be only the early harvest to salvage. You know that as well as any farmer does. So I tell you once more, eat while there is bread or you will not live to celebrate the Risen Christ again."

"If Brother Haganrih allows it, I will." He met her glare with one of equal force. "Is that all?"

She was about to say yes, and then she hesitated. "I found spiders in the muniment room yesterday, in the old chest, not the new."

"With the deeds and the gold?" he asked, horrified by the omen.

"Yes," she said.

This time he Signed himself without thinking. "Sweet, White Savior Jesus," he whispered, using the old soldiers' oath; he would have to atone for it later. "How many?"

"Five that I could find. There could be more." Her face was grave. "I haven't mentioned it to anyone, not even to Brother Erchboge."

"I should hope not," said Brother Giselberht with feeling. "Five! With the gold and the deeds. Lord of Salvation! And there could be more. You believe there could be more?"

"I looked but could not see them, but—" She broke off, then stared at him. "I will look again if you want."

"No," he said at once. "Leave it is as it is. You have seen the omen and told me. That's sufficient." He wanted to ask her if she had discovered anything else, but the dread that she could tell of things still worse kept him silent. He tucked his arms into his sleeves. "Well, you have told me. Is there anything more?"

"A minor thing." She gestured to show that it was not urgent. "It concerns Captain Meyrih."

"Is he well?" asked Brother Giselberht.

"It's his eyes. They're starting to fail him. The moon is on them. He does not wish to give up his command, but he tells me that he cannot see well enough to perform his duties. He is afraid that he cannot protect the fortress as he must." She tried to look reassuring. "His children are all but grown, and he has your vow of protection, but he does not want to become one of those old, blind veterans who sit in the sunny corner of the barracks and drone on about the great battles of the past." She shared his sense of indecision. She lifted her skirts to her knees again. "Let me know what you would like me to do when I come again in four days' time."

Brother Giselberht nodded slowly. "This is unhappy news," he said. "Captain Meyrih taught me half the skills of war."

"He is nearly forty. What else can he expect?" Ranegonda did not wait for an answer. With a quick movement she was at the door, tugging on it to get it open.

"I will pray for an answer," said Brother Giselberht, watching as she closed the door behind her; he went and secured the stout wooden bolt before returning to the monastery grounds and his interrupted meditations.

Ranegonda hitched up her skirts and climbed back into the saddle on her feisty dun, saying nothing to the two armed men who escorted her. She clapped her heels to the dun's sides and started him cantering away from the monastery, signaHng to the men to come with her. Her features were set, showing none of the emotion that gripped her; it was not for her to reveal to these men how little she had gained from speaking with her brother, who was becoming a stranger to her. It was more than

their growing alienation; she was upset by Brother Giselberht's reticence and his indecision.

Reginhart, the younger of the two armed men, spurred his horse to catch up with her, calHng out "Madchen! Madchen!" as he went. The older, Ewarht, held his distance.

Slowly Ranegonda pulled in her horse, letting him fall back to a slow trot. "I ask your pardon," she said to Reginhart as he caught up with her. "It was unwise to do that." Her eyes sharpened. "But I am called Gerefa, not Madchen."

"It was a fine race," said Reginhart, patting the neck of his bay and ignoring her correction. "I like a good run now and then."

To the north the Baltic Sea stretched out, more restless than it had been an hour ago. Ranegonda pointed to the horizon. "By tomorrow there will be rain."

"The harvest isn't complete," said Reginhart.

"We will have to work tomorrow morning, as long as we can, to bring in as much as possible," she said. "The men will have to go to the fields with the farmers or we will not have bread after the Nativity Mass."

"Some will refuse," Reginhart predicted. "It is not mete that fighting men should work like peasants."

"It isn't fitting that they should starve, either, but that will happen if they will not help the harvest," said Ranegonda sharply. "You need no bad omens to see in what plight we stand. We have less grain in storage now than is prudent, and if we lose any of this harvest, it will go hard for us." She looked to the right once more, studying the sea again. "The storm is a bad one."

"You're certain," said Reginhart. "The season for them is a month away yet."

"All the signs point to it." There was also the throb low in her leg, which was more reliable than all the signs together. "We will have to be ready."

"How can we be, with most of the rye still standing in the field, and half the wheat?" He sounded angry because he was frightened and unable to admit it. "You are a woman, and you are taken with odd notions."

"I am Gerefa of the fortress," she said in a tone that permitted no argument. "And I tell you that we will have to work like the lowest slaves if we're not to starve this winter."

Reginhart wanted to protest this, but as Ewarht was now just a length behind them, he kept silent; it was not his place to question what

Ranegonda said as long as her brother kept to the monastery. Ewarht was a stickler for correct form and he would not look favorably on Reginhart if he thought the younger man was challenging their Gerefa. He squinted into the sun ahead of them. "We will not be at the fortress much before dark." It was true enough, and safe to say.

"We can push the horses," said Ewarht.

"No," said Ranegonda. "We can't afford having one go lame, or risk a fall. If we keep moving we will arrive while there is still light, and we'll be safe."

There was a vast expanse of forest reaching along the wide lowland where they rode, and within that forest there were rumored to be bands of desperate men. To venture through the close-growing trees was hazard enough in daylight—at night it was egregious folly. Reginhart pointed toward the first of the trees. '"Keep your sword out," he recommended to Ewarht, who had already drawn his.

Ranegonda reached for the scabbard that hung from the high pommel of her saddle. She drew her short-sword and said to the others, "Good. We're prepared."

"The road is poor," said Ewarht as if they had forgotten since they rode over it half a morning ago.

"Be careful, then," said Ranegonda. The sword felt heavy in her hand, and she had to keep from balking at its purpose. Twice in the past she had been forced to fight off robbers, and both times had left her shaken and nauseated. She did not want to have another such encounter.

"You should take a larger company of men with you," advised Ewarht as they entered the cover of the trees. It was darker here, and the sunhght, by contrast, more brilliant and red, making their eyes water when they moved through the slanting rays.

It was hard to pick their way along the narrow, rutted path through the trees. For the first quarter of their passage they went without speaking, each of them listening for inappropriate sounds, staring into the green darkness for the flash of metal. They were forced to ride in single file, which increased their vulnerability to attack from the side. Reginhart used his sword to swipe at the bushes as they passed, making sure that no one lurked within them. As startled birds rose in loud cries there was a constant rustle as animals moved away from the intruders.

"If winter is coming early," said Ewarht from the rear after they had gone some distance, "it is time to start hunting. There are boars and stags to bring to earth."

"That there are," agreed Reginhart from the front. "We can hunt boars later, but if we're going to chase stags it had better be while the

ground is still hard." He coughed once. "And before the wolves get them."

"I've already considered that," said Ranegonda, trying not to permit her nervousness to show. "After the first storm will be time enough for stags."

They went on a way with only the smacking of Reginhart's sword and the fall of their horses' hooves to mark their passage. Then Ewarht said, "If you can read the signs for early winter, surely the wolves can, too."

"Very probably," said Ranegonda, thinking that the forest was much larger and deeper than she remembered from earlier that day. "Creatures have learned these things of old, and their knowledge is vast."

"I saw scraps of red cloth tied to the branches of the oak tree in the field to the west of the fortress village," said Ewarht.

"Some of the peasants try to serve God and the old ways," said Ranegonda, who had occasionally left yarn tied to the branches of trees when she was younger. "If they want the oaks to carry messages for them, we must pray that God will show them His Mercy in their ignorance."

"Brother Erchboge won't like it," Ewarht predicted, listening intently as they continued on. "He says that those who leave tokens for the old gods will suffer for it when they have to answer to the White Christ when He comes. There is no place for the old gods where the White Christ lives. The White Christ forgives all sin, but only the sins of those who believe in Him."

They were almost at the edge of the trees now, and beyond was a stretch of fields, then a gathering of stone-and-thatch houses and a fenced yard of cut trees at the foot of the only real promontory on the coast for several leagues in both directions. It was there that their fortress stood, taking up most of the high ground, an irregular oblong surrounded by a stone parapet and guarded by two towers instead of the usual one, the taller by the landward gate, the shorter on the highest point of ground above the beach; it was there in the uppermost chamber a huge brazier burned night and day to guide ships at sea.

"We were lucky this time," said Reginhart as the last of the sun's rays struck his leather-and-scale armor. "At another time we might have to battle our way out of there."

"At another time, we will be hunting," said Ranegonda, determined not to appear frightened. She returned her sword to its scabbard. "If we catch more than stags or boar, it will be the misfortune of the outlaws we find." She wanted to force her dun to canter, but she knew the gelding was tired, and so allowed him to continue to trot. She said to

the others, "We do not have to go in single file here." The road was a fairly straight track, wide and rutted from the constant traffic of woodcutters with carts who ventured into the forest to cut trees. Today it was dusty, gritty with sand, but once the rains came, it would quickly become a bog.

They reached the village and passed down the only street. Those few villagers who were not yet within doors stopped and went down on their knees as Ranegonda went by, though one of the men held up a talisman to ward off evil; the old gods did not like women commanding the fortress.

When they started up the hill toward the massive wooden gates, Ranegonda could hear a wooden horn sounding, marking her return. Just as they reached the gates, they swung ponderously open, permitting Ranegonda and her two armed men to pass inside. As they drew up in the courtyard, grooms with slave brands on their foreheads came running out to take charge of the horses.

Because of her skirts it was an effort for Ranegonda to swing her leg over the saddle as she dismounted, and she set her jaw in the hope that her weak right ankle would not buckle as she put her weight on it: she managed the chore well enough and handed the reins to the nine-year-old boy who had charge of the horses and the dogs of the fortress. "Make sure they have grain tonight," she told the boy.

He bowed, his knees slightly bent. 'That I will, Gerefa," he said, and took the reins of Ewarht's and Reginhart's mounts as well.

The fortress was ugly, utilitarian in the extreme, with two blunt towers and little windows which were covered with parchment in winter when it was often colder inside the stone edifice than outside. Wooden buildings occupied most of the eastern half of the courtyard, housing for the men-at-arms and their families; the stables, kennels, coops, and slaves' quarters were on the west side, with a wooden Common Hall in the middle, the stone kitchens, baths, and bakehouse behind it. In summer the place remained dark and held the dank heat with tenacity. But it gave protection and safety, and that made it beautiful to Ranegonda. A second call on the wooden horn informed all the inhabitants of the fortress that Ranegonda was inside the walls.

"Madchen," said the monitor as he approached her. his head lowered to show respect to the office she held. 'The White Christ be praised for your swift return."

"And my escorts be praised, as well," said Ranegonda as she Signed herself.

"Yes. Most certainly," said the monitor, who wore an owl's claw on

a thong around his neck. He lowered his head still further, knowing that what he told her next would not be welcome. "Your brother's wife would like to speak to you. She is waiting in the sewing chamber."

Ranegonda heard this out stoically. "All right," she told the monitor. "I will be with her as soon as I have set my cloak aside. Tell Pentacoste that I do not want to come in a dusty cloak smirched by the stains of travel." It was nothing more than a delaying tactic, but it was plausible enough, and the monitor accepted it without reservation. As he backed two steps away from her, Ranegonda steeled herself for her necessary conversation with her sister-in-law.

Text of a dispatch from the customs officer at Hedaby to Hrotiger in Rome; carried overland by a party of merchants bound for Salz in Franconia, transferred to another company of merchants and taken as far as Constanz in Swabia, and transferred there to a courier of the Bishop of Milan bound for Rome. Delivered December 19, 937.

To the factor and agent of the Excellent Comites Saint-Germanius, Hrotiger in the city of Rome, greetings at the end of September.

This is to inform you that the first of five ships hound from Staraya Ladoga has landed. The cargo consists of furs, amber, silk, brasses, and spices. The taxes have been paid upon the value of the cargo, but it cannot yet be released until the other four ships have arrived or been accounted for, as the full value of the goods cannot be assessed until that time. We will hold this cargo in our warehouse, and when all parts of the shipments have been received, we will arrange for their shipment to Rome, in accordance with the orders of the Comites Saint-Germanius.

The Captain of this first ship to land, the West Wind, has informed me that the Comites sailed aboard the Midnight Sun, which is the largest of the other four ships. It is expected that the rest will arrive shortly if they have not been damaged or sunk because of the tempests. There have been four storms in the last ten days, and many ships have put in to port to find shelter. Many of the sailors newly arrived in Hedaby have said that other craft were in grave danger from the storms. Therefore we are hesitating to state more than that we have not received confirmation of any wreckage from the Comites' ships. We are just now seeing ships in the harbor that were expected more than a week ago. These have brought word of two of the Comites' ships, the Savior and the Golden Eye, which have been sighted on the water and bound for this port. We have not yet received any word about the Harvest Moon or the Midnight Sun, either to the good or the bad. In duty to your master, we must tell you that there have been

reports of other ships sunk, although none of the sightings have been part of the Comites' ships we have already mentioned, nor have we been informed of jetsam discovered belonging to him.

It is also possible that pirates have attempted to seize the cargo carried in those ships, and if that is the case, it will be some time before we will know of it, for pirates carry their plunder far from these harbors, the better to conceal their deeds. It is possible that if pirates have taken the cargo they may also demand ransom for your master, in which case you will know of it before we do at Hedaby. We pray that no such misfortune has befallen the Comites, but pirates are desperate men who care nothing for their own safety, and will venture onto the waves when prudent men search for safe harbor.

Should there be reason to send another report, it will be dispatched to you as soon as possible, in order that you can act upon whatever information is given before the first of the year. Your master has provided instructions in the event of any difficulty arising from his voyage, and we will act upon them if it becomes necessary. If we have not received the cargo of all five ships by the end of the year, we will release those portions of the cargo which have arrived and arrange for them to be carried south to you.

With the wish that God favors you and the cause of your master and brings you health and prosperity, we vow continuing service to you.

the sign of the customs clerk by the hand of Brother Thimofei

For the first time in four days the sky was showing patches of blue amid the scudding clouds and the waves had ceased to maul the shore; this was a welcome relief from the ferocity of the storms that had ransacked the Baltic, and those who emerged from their houses to examine the destruction left behind also saw the splendid sunshine.

Ranegonda ordered half her men out of the fortress to assess the damage, and she herself led the small party down the steep trails to the beach, to see how badly the cliff below the fortress had fared in the relentless battering of wind and water.

There were tangles of debris on the beach, some of them driven up the rough sands to the base of the cliff beneath the seaward tower, a formidable testament to the fury of the sea.

Aedelar shaded his eyes and looked at the mess. "At least we can burn it, once it's dry."

"An excellent notion," said Ranegonda. "Tomorrow I want parties sent down here with sledges; load them up and carry the wood up to the fortress." She shaded her eyes as she looked westward. "Today we have more urgent work. I want each of you to ride for an hour along the beach, some to the east and some to the west. The tide will be at its ebb in an hour." she said. "Be diligent. If there has been other damage, I will know about it."

The men ordered to accompany her glared but did not defy her order.

She looked at the small group. "I know you don't like this duty. It is probably going to be for nothing, and the work is tedious. At the same time I know it is a risk as well as you do, for there may be those seeking to reap what harvest they can from the storm, and they will want to drive you off from their discoveries, which cannot be permitted. Be certain your swords are at the ready and go no faster than a trot. Keep a watch for traps on the beach, as well. Stretched ropes, pits in the sand—you have seen the tricks that are played. You do not want to lose your horse to these carrion." All but one of them heard her out with respect, for in the two years she had acted for her brother they had come to realize she had a most unwomanly good sense. The one who resisted was recalcitrant by nature and his behavior surprised none of them. She decided to improve her position. "I will ride with you, so that you will—"

Captain Meyrih, whose eyes were clouding over with white, shook his head. "It isn't necessary, Gerefa." Like most of the soldiers, he was not quite certain what title to use for her, and chose to call her by her administrative title than her military one, which Ranegonda herself preferred.

"It is my obligation," said Ranegonda in a tone that accepted no argument.

The storm had robbed the beach of some of the finest sand that had smoothed it through the summer; there was coarser sand more evident now, and by the end of winter the storms would wear the beach down to pebbles. With the spring and calmer weather, the fine sand would return. Right now there was enough fine sand left to make walking awkward, but the coarse sand contributed scratches and minor abrasions where it rubbed at the skin, and once inside boots and leggings, it was a minor but persistent torment, one that would be paid for later in scrapes and blisters.

"It's hard walking," complained Reginhart.

Ranegonda did not answer him directly. "Aedelar," she said to the

man nearest her. "Fetch the horses. They should be saddled and waiting. Take Ewarht with you."

Aedelar touched his leather cap and looked back up the slope. "We'll have to bring them down on the east, beyond the stream. It'll take a while, but it's safer. The footing isn't good enough here." He indicated the rocks on the face of the promontory. "It could crumble if we bring the horses this way. And it's a hard climb."

"You're right," said Ranegonda. "Don't take any unnecessary risks. We haven't horses to spare."

"I know," said Aedelar impatiently. "And just four mares in foal, too." He looked toward the path up to the fortress. "It's the only high ground for leagues. Right now that seems unjust."

The others laughed, and Ewarht cocked his head toward the cliff. "We'd best go get the horses."

"They're not going to come of their own accord," said Aedelar in concession, and trudged off through the damp sand, Ewarht walking slightly behind him.

Ranegonda had hitched up her skirts so that she could walk more easily through the sand; she envied her men their short bliauts and thick leggings—skirts were the very devil in sand, or scrambling down the trail, and with her weak ankle they were doubly treacherous. "I want note made of any wreckage we find. Arrange to bring lost cargo to the fortress. There will be a commissioner from King Otto arriving before the end of the year and he will demand an accounting of ships lost off this coast."

Reginhart lifted both his arms to show how much beyond them such an investigation would be. "If King Otto wants to know that, then he ought to build another fortress somewhere between us and Laboeric; the one at Wagrihoved is useless, nothing but—" He shook his head emphatically. "Two days east and two days west! We can't patrol the sands that far."

"An effort must be made," said Ranegonda firmly. "You are as aware of that as I am." She did not fold her arms but there was an unmistakable authority in her stance, and none of the men wanted to defy her. "Ride for an hour to the east and to the west. Unless there are parts of a ship to be found, or other signs of a wreck at sea, there is no reason to go any farther. I will answer for any questions the commissioner may have."

"And if another storm comes in?" asked Reginhart.

"Then return to the fortress, of course, though there will be no more storms for some days if I read the signs right," she said, losing patience with him. "You're not a fool, Reginhart."

The others laughed, but Reginhart looked annoyed. "As you say, Madchen." Of all the titles she could have, "Madchen" was the least pleasing to Ranegonda, for she hated being reminded of her unmarried state. Reginhart sensed this and took full advantage of her dissatisfaction.

"If I learn that any of you has been lax in your search, there will be a price to be paid, I promise you." She put her hands on her hips and looked around at her men. Satisfied that there would be no more resistance for the moment, she went on. "If there is treasure found, notify me at once and the treasure will be placed in the muniment room to wait for the commissioner. At that time, it will be decided how much of the treasure will be given to the finder."

"King Otto will keep the lot for himself," said Berahtram, who had lost an eye in battle with Otto's father.

"King Otto has not done so dishonorable a thing," said Ranegonda. "He will see that the finder—if anyone finds anything—is given his due." She pointed to the west. "You can lead the men in that direction, Berahtram," she went on. "Make sure that you check the inlets and the places where streams fall. I will lead the rest to the east."

"Be careful of the edges of the marsh," said Captain Meyrih. "It is not safe to venture too far toward the marshes."

"I know," said Ranegonda with kindness. "And I thank you for your concern for the welfare of us all." She started away toward the swath of wet sand where the spent waves came. The footing was more secure and provided a better view of the fortress above them. "I want everyone to be careful. If you suspect danger, take no chances."

"A few peasants picking over the bones of a ship, what is that to us?" said Reginhart.

"It could be a great deal if the peasants carry arms, or if they are not peasants but pirates," said Ranegonda. "It was not so long ago that you were set upon by just such a group." Her reminder was pointed, and all of the men knew it: Reginhart's recklessness had almost cost him his life a year ago.

"I was foolish then. I will not be so now." Reginhart cocked his head, making the movement a challenge to the others.

Ranegonda paid little heed to him but continued toward the sea. "I am expected to account for all the men at this fortress. If anything befalls you—any of you—I will have to answer for it in my brother's stead." She looked back over her shoulder at them. "You will follow my orders, like them or not." Just as she said this, her skirt slipped from the hitch in her belt, and she tripped over the hem, falling forward with her hands straight out in front of her. They struck the end of a black.

broken beam poking up from the sand, and a long, shallow wound gashed the inside of her left arm. Ranegonda swore as comprehensively as any trooper, damning her limp and her weak right ankle; she wiped the welling blood away with her skirt. She sat up, refusing to be embarrassed by her fall. "This is just what I meant when I warned against mishap. Any one of you could be injured in this way. Including a horse; such an injury as this could lame him or destroy a hoof, and that would be the end of him."

"The scrape looks bad," said Berahtram, coming toward her.

"It is not enough to bother with," she countered, getting to her feet as she said this. "It will scab over before we are back at the fortress."

"You will have to see the herb woman," said Reginhart.

"If there is any cause, I will," Ranegonda answered.

"Are you fit to go on?" asked Captain Meyrih, trying to peer through his blighted eyes to make out what was happening.

"Of course I am fit," said Ranegonda in exasperation. "It is little more than a scratch. Let everyone take it as a lesson, and be careful as you go." She glared around the sands, wondering inwardly what the injury meant, what omen was it?

"Let me look at it," Reginhart volunteered.

"It's nothing," Ranegonda snapped, rubbing her arm against her skirt and leaving a red smear. "Do not be distressed." She looked away from him and regarded the waves while she brought her temper under control.

The men waited silently while Ranegonda paced a short distance away from them, then came back. Captain Meyrih said in an under-voice, "That was badly done, Reginhart. Badly done."

Reginhart did not try to defend himself, knowing it was useless.

As Ranegonda returned, her face was unreadable. In the harsh sunlight the scars on her cheeks and neck were starkly visible, reminders that she had survived the Great Pox. Her long braids were knotted at the back of her head, the way long-haired soldiers went into battle. She looked at the men. "I want no one taking loot for himself. Is that understood? If anyone is caught doing such, he is banished from the fortress. The nearest Saxon holding is Laboeric. It will take you two or three days to get there, if you think you can reach it on your own, on foot. If the wolves or the bear or the brigands don't kill you before you arrive. Your wives will have to remain here until the King's commissioner decides what to do with them and your children." She looked at each of them in turn. "I will not hesitate to banish any of you who loot. The King's commissioner will expect it of me, and my brother will demand it."

Berahtram answered for all of them. "Banishment is better than having a hand struck off."

"God's Truth," said Captain Meyrih, and Signed himself.

Ranegonda folded her arms. "I want no faithless men fighting beside me.

"May God preserve you," said Berahtram promptly. "And keep you in His vision." He glanced at the others. "We all say it."

There were mutters and nods, which Ranegonda accepted without too much inner questioning. She came closer to them as she knotted her skirt and tucked it into her wide leather belt, checking to be certain it would not come loose a second time. "All right. Be alert and watch around you. Have a care of what you do and take no chances. Those of you who carry horns, keep them to hand, in case you need to summon aid."

"It might not arrive in time," said Reginhart with ill-concealed eagerness. "Better to fight and be done with it."

"And risk more men, who would have to search for you without warning? Put the outlaws at the advantage? That is not bravery, it is foolishness, is it not?" Ranegonda inquired in great politeness.

Reginhart sighed, resisting capitulation. "It is a coward who sounds his horn for a skirmish."

"Then the great Roland was surely a coward for sounding his," snapped Ranegonda, tired of these protestations. Her ploy worked, for Reginhart looked away, his face darkening.

Any further animosity was stopped as Berahtram pointed to the east; at the crest of the first rise to the fortress there were horses. "There," he said. "We'll be at it soon enough. A good omen."

Ranegonda was relieved to see them, and motioned to the men to come with her. She went silently, concentrating on walking without limping. She did well until they reached the place where the little stream made a glittering swath through the rocks and sand, and there she lost her footing again. Her arms flailed as she strove to recover herself without falHng.

"Take my arm, Gerefa," said Berahtram, coming up beside her. "These streams are tricky."

"My thanks," Ranegonda muttered, and kept doggedly on to where the wide path from the fortress came to the beach.

Ewarht offered reins of the dun gelding to Ranegonda first, in respect for her position as Gerefa, and did her the courtesy of looking away as she struggled into the saddle, her skirt catching on the tall cantel as she swung her leg over. Then he let the others select the mounts they

preferred as he climbed into the saddle of a raw-boned blood-bay mare. "May I ride with you?" he asked Ranegonda.

"If you like," she replied as she gathered in the reins while the gelding, restive after three days in his stall, scampered and curvetted. As she brought the horse to order, she called out, "Berahtram, you and Aedelar lead them to the west. Take half the men. The rest come with me." She pointed into the east, realizing that beyond her sight stood the Monastery of the Holy Cross and her brother and the White Christ. Quelling the anxiety that filled her, she started her dun moving to the edge of the spent waves, where the footing was best, and with an effort held him in to a trot.

Coming up beside her, Ewarht remarked, "Away in good time, Gerefa; it isn't much past midday."

"Yes," she agreed. "That gives good time until sunset." She had her hands full with the dun, but still managed to watch the beach for signs of wreckage. Behind her rode Karagern, Faxon, Amalric, Rupoerht, Ulfrid, Walderih, and Culfre, all men who were not on watch, as were the half-dozen men now mounting up to go west with Berahtram and Aedelar. The oldest of the seven with Ranegonda, Ulfrid, was thirty-one; the youngest, Karagern, was fifteen.

"Do you expect to find anything?" Ewarht asked when they had gone a short distance along the beach.

"The sea alone knows that," said Ranegonda pulling her dun in more firmly. The horse tossed his head in objection, then settled down with a huff.

"He wants to run," Ewarht observed. His own mare was more mannerly, settling into her pace methodically.

"And then he'd be too tired to be of any use on the way back," said Ranegonda. "He'll be fine once he works the knots out of his legs."

When they had gone a bit further, Ewarht commented, "There have been more raiders on the beach, these last few years."

"There have been," she said, not wanting to reveal how deeply this troubled her. She looked toward the land, where a few straggling trees hovered at the edge of rocks and sand, offering protection to anyone waiting there. She stared into the green darkness as if by will alone she could discover the presence of the outlaws known to live in the vast forest beyond. "If they come, we will fight them off."

"Certainly," said Ewarht.

There was driftwood piled up at the high-water line, most of it worn and weathered. The mounted party paid little attention to these ancient veterans, looking for new wood and scraps of cloth from torn sails, or bales and chests of lost cargo.

"That's a strange place," said Faxon behind them, pointing to a tangle of old, water-twisted tree-trunks. It was said that those who wanted to appease the old ocean god came there at the full of the moon to leave offerings, and that to find it empty during the day could bring ill-fortune to the finder.

"Best to stay clear of it," advised Ewarht, who knew the rumors as well as anyone. "Day and night."

A few of the men laughed, but most of them took the precaution of Signing themselves as they went by; Culfre averted his eyes for greater protection.

"Tell me," called out Rupoerht once they were safely beyond the dangerous place, "how much longer do we ride this way?" He pointed to the right, where the trees were nearer.

"I ordered an hour in each direction," said Ranegonda. "There is a way to go yet." She swung around as far as her saddle would allow. "If you are troubled, draw your sword."

None of the men did that, although three touched the hilts, to be certain that the blades could be drawn quickly; their occasional conversations ceased.

Gradually the horses' trot slowed to a jog, steady and easy to ride, covering distance at twice the speed a man would walk. Their shadows, which had been beneath them and toward the sea, were now beginning to move to the front of them as their search went on; when the heads of the horses could be clearly made out in the shadows, they would turn back. The wind out of the north was hard, slapping at them as they rode, keeping the sun from warming them.

They were almost at the limits of their ride when Amalric spotted something drifting a little way out in the water. He rose in his stirrups and pointed. "There! At the last waves."

The others reined in, and Ranegonda pulled her dun around to face the sea.

"It looks like a chest, a big one. I'll try to reach it." Faxon swung out of his saddle, handed the reins to Karagern, and waded off into the water, yelling back, "It's heavy. Locked, too."

"Bring it ashore," Ranegonda ordered, and rode a little way into the water. "Is that all?"

The others were looking more closely now, Amalric shading his eyes. He pointed again. "There's another one. Over there, near the cove."

"And something else," called Faxon. "It looks Uke a merchant's bale. I don't know if it's cloth or what."

"Ah!" Ranegonda exclaimed. "Retrieve them all as well, if you can. We'd best search there." She signaled to Ewarht. "Help bring them

ashore and rig a sled to drag them back to the fortress. If they are left on the beach overnight, we will not find them in the morning. There's rope on Faxon's saddle. Use that if you need to."

"Yes, Gerefa," he said, riding into the water to help Faxon drag the chest away from the sea. "We'll tend to it." He waved her away.

"Gerefa," Karagern shouted, "there's a seal on the lock. It has wings."

"Then perhaps we can learn who owns it," Ranegonda answered loudly. "Make note of them all." She swung her arm, gathering the others. "Walderih, Culfre, Rupoerht, Ulfrid, come with me," Ranegonda said, leaving Amalric, Faxon, and Karagern with Ewarht. She set her dun trotting more briskly again as she headed for the cove beyond the low outcropping of boulders.

The others rode after her, keeping to the edge of the water as she did.

Ranegonda drew her sword as she rounded the boulders, half-expecting to confront thieves scavenging for flotsam and jetsam. But there was nothing waiting for them but a half-dozen bales of furs, a few more bound-and-locked chests, and what appeared to be part of the bow of a trading vessel and a section of mast, some of it already buried in sand. She drew her horse in and raised her sword so that the rest would stop.

"There was a wreck," said Culfre, for all of them.

"Two days ago, judging by the sand," said Ulfrid. He sheathed his sword and looked at Ranegonda speculatively. "Well?"

She returned her sword to its scabbard, making up her mind. "Walderih, stay mounted and hold the horses for us. The rest of you, dismount and come with me. Keep your hands free and your knives ready."

The men did as she ordered, only Rupoerht hanging back as he came out of the saddle. "It could be a trap," he said.

"There would be signs of it," said Ranegonda. "The sand hasn't been disturbed since that wreck came ashore." She started toward the portion of the mast that thrust into the air. "It looks as if the ship broke apart, and drifted here afterward. We will be finding pieces of the ship for months to come, I would guess." She pointed to a section of steering oar. "See that? It is from the rear of the ship, and this"—she indicated the portion of bow—"is from the front."

The men with her looked, and Rupoerht Signed himself. "There will be bodies."

"Probably, unless the fishes got them. Or the outlaws have been here already. Look down the beach, one of you, to see if there are any dead," said Ranegonda, refusing to be shocked by what she saw. Was there an omen here, she asked herself, and if so, what did it mean? She studied

the wreckage more intently, seeing here a spar, and there more remnants of sails.

"Or the old gods," added Culfre, also Signing himself.

They went closer to the water-logged sections of wood, Rupoerht murmuring a few words for protection. "The ship ..." He made a short gesture at the destruction they saw. "It could not be saved."

"We had better find some identification, if there is any," said Rane-gonda, deliberately stepping over the broken mast. "The King's commissioner will demand we show him tokens of the wreck. Otto has said he will have full accounting of all losses in his waters." She made a sweeping motion with her arms. "Search this cove. Search it well." Taking her own order, she went directly toward the splintered bow, approaching it carefully.

The bowsprit was shattered, standing up from the sand with the bow below, held in place by the few remaining ribs. The nearer Ranegonda came to it, the more it seemed to be a cupped hand with a single finger pointed skyward; she felt herself go cold, starting with her wet feet and ending near her heart. There was a riddle in this ruined ship, but she was unable to guess what the answer to it might be. Reluctantly she stepped inside the curve of the ruined hull.

"Gerefa!" called Rupoerht from a short distance behind her.

Ranegonda did not answer him at once; she stood in the shadow looking down at the motionless figure lying beneath a few pieces of deck planking, his side-turned head half buried in sand. He was pale where he was not bruised, and his few scraps of clothes were in tatters. Only his upper chest and shoulders were visible above the planking; the rest of him lay under the rubble and sand. One arm was extended beyond the smashed planks; a small hand, swollen and discolored, at the end of it was limp. "God of the Ravens!" Ranegonda whispered, and stumbled toward the motionless figure, reaching out as she did to hft the wood off' him, steehng herself for the damage she was sure she would encounter. As she struggled with the heavy planking, the gash on her arm opened with her eff'ort, and began once again to bleed.

"Gerefa!" shouted Rupoerht, louder and nearer.

"Be quiet!" she ordered over her shoulder as she levered a second section of deck off* the still form, revealing more of the torso, which was crossed with old scars but was mercifully undamaged but for bruises. She turned to motion the soldier back from her and almost fell as her ankle gave way. As she reached out to steady herself, her injured arm brushed the face of the body, leaving a bloody smear across his mouth.

Rupoerht had reached the curve of the bow, but he came no farther. He Signed himself and moved back. "Do you need help, Gerefa?"

"Not yet," she said, continuing to work to free the body. "But we will need a way to carry him. Go. Tell the others to prepare a shng for ... for him." She had a dread of calhng the dead dead in their presence, and never more so than now.

Once again Rupoerht Signed himself, glad for a reason to move away. "All right. Til tell them."

Ranegonda ignored Rupoerht's departure and knelt down beside the man, trying to clear away the sand from around his head, working steadily until she had succeeded in freeing him from the sand. She touched his face and was surprised that the flesh was not colder; she brushed the dark, loosely curling hair back from his brow and studied his beaten features, trying to discern what he might have looked like before the storm savaged him. Then she started to rub her blood off' him.

The fingers of his out-flung hand moved, closing weakly on her wrist.