MY starting pay as a furniture salesman was £5 a week, which seemed quite a lot, and the day after I joined the business I sold a £12 dining table to a woman who had come into the shop for a mirror.

It was a pleasurable experience, not because I wanted the woman to part with money she should have spent on a mirror, but because I honestly felt she would be better off with a dining table.

This is a principle I have applied in business since, because I believe that it is a salesman’s job. The buyer must be convinced that what he wanted would not be good for him and that what he does not want would be very good for him.

I became a good salesman and I surprised my father and I believe we were both rather proud.

Day by day I began to enjoy procuring other people’s confidence—watching them relax and show trust in me. It was pleasurable to see the wary look dissolve, to know that they believed that good things were ahead for them and that I would be the provider.

This is not to be pompous; it is, I believe, the essence of successful and honourable salesmanship.

I developed into a relaxed seller and, consequently, more of an Epstein for we were very much a business family, though, I hope, never a greedy one. Finding the job easy allowed me more time to have a hard look at the layout of the store—at the design and the colour schemes and at the products themselves. I was, and still am, very interested in the way things should be displayed and I have a self-devouring passion for quality.

In those days, the Walton store was not exactly a candidate for a design award. Our window displays were, I thought, rather awful and I horrified the conventional furniture men by doing outrageous things with the pieces.

I placed chairs in the windows with their backs to the window-shoppers. Backs of chairs in view? Unheard of! Yet in every home you see the backs of chairs in the fireside pattern … indeed, you cannot enter a room without seeing the back of a chair.

I was very keen on splayed legs. They were just on the way in at that time, because slowly the post-war austerity hangover was diminishing and sellers and buyers were reluctant to return to the ugliness of the 1930-ish design.

New young men with degrees in Art were discarding moquette, stripping the curls and twirls from sideboards and chairs, and bringing in clean lines and new fabrics. White became an ‘in’ colour, wall-paper became fashionable again and everywhere that was anywhere, suddenly, there were splayed legs! I was entranced by the possibilities.

My father, not convinced that I wasn’t running before I could stand but also thrilled to see me settling to something at last, decided to have me apprenticed to a city furnishing store—The Times, in Lord Street, Liverpool.

I worked there for six months, still on £5 a week, but I was beginning to feel that I was worth a good deal more. Still, I learned a lot about window-dressing and very much more about people and their desire to be convinced and persuaded. As a reward for my work the Times gave me a Parker pen and pencil, the first of which, many years later, I loaned to Paul McCartney to sign his first contract with me.

Of course, I often needed more money and when I was hard up I asked my father for a pound or two. He always met my requests but I hated asking. That I loathed profoundly and though I shall never again have to seek money from anyone, I have a deeply imprinted recollection of the unpleasant moment when one has to say … ‘I am a little short of cash. Could you possibly lend me some?’

Honourably discharged from the Times, I returned to the Walton store with another new suit and here I was, I thought, developing into a worthy inheritor of a stable, profitable business which I had learned to like.

I was settling down; the designing of the store was becoming my own responsibility and all in all, my mother and father were really quite pleased with their Brian. The future seemed firm and bright and assured.

But, on December 9th, 1952, a letter came from a grim and grey and joyless office in Parnall Square, off Renshaw Street, Liverpool, to tell the pleased-with-himself young son and heir that he was to present himself for a medical examination to ascertain his medical fitness for the army.

I was appalled and shocked though I shouldn’t have been since this two-year punishment was then a routine, predictable segment of teenage life. I viewed it as a wasteful gulf but, in fact, for me it turned out to be immeasurably worse than that. For if I had been a poor schoolboy, I was surely the lousiest soldier in the world, not excepting the sad, demented creatures who bianco their trousers and eat their webbing belts in their attempts to fiddle a discharge. I passed the medical which, apart from a cough or two, was not, I felt, very stringent, and I applied to join the R.A.F. because I believed it would be easier than the army. But with the quaint logic of the armed forces, I was allocated to the army, as a clerk in the Royal Army Service Corps. Basic training was at Aldershot and if there is a more depressing place than this in all Europe, then I would not be interested to know of it.

It was like a prison and it was squalid and meaningless. It was cold and hostile and I did everything wrong. I turned right instead of left, and turned about instead of at ease, and if I was told just to stand still, then I fell over.

I entered 1953 in a mood of immovable pessimism and I was not cheered by evidence that most of the lads with me were taking their hardship with fortitude. Several of the public-schoolboys who had shared my moans in the first few weeks were snatched away to become officer-cadets but naturally—for the army is not always wrong—I was not included.

I cannot imagine anything worse for morale than Lieutenant Epstein in charge of a platoon of men under heavy mortar fire.

The year 1953 was, of course, the year of the Coronation, and though I was a rotten soldier I had a perverse wish to be on parade in London that day. I suppose it was the splendid stage-management and the majesty of the thing, but I wasn’t nearly good enough to be used so I went out of barracks and got very drunk instead—after a tour of pubs and clubs which left me with three-halfpence and a disagreeable headache.

My failure to be selected as an officer did not, however, prevent me from impersonating officers and one night this involved me in trouble.

I had deviously secured a posting to Regent’s Park barracks and I used to enjoy off-duty life in the West End for I had a lot of relatives in London. On this particular night I had myself brought back to camp in a large car. It slid gently to a halt outside the barrack’s gate. I marched into camp wearing—rather pompously I’m afraid a bowler, pin-striped suit and, over my arm, an umbrella.

The guard saluted me and the guard commander saluted me and two wretched convicted deserters, wearing denims and carrying buckets, jerked their heads in an Eyes Right. Also, a myopic clerk, who worked at the next desk by day, peered at me and said: ‘Good night sir.’ All of which I allowed to pass by without a murmur one way or the other.

The orderly officer did none of these things. He came from behind a white-washed wall like a cat, and marching into the baleful yellow glow from the guardroom, he barked: ‘Private Epstein. You will report to the company office at 10.00 hours tomorrow morning charged with impersonating an officer.

I was kept in barracks for some days—not for the first time. This, for me, was the worst punishment because it deprived me of my only compensation—the freedom of London after 6 p.m. And within ten months of joining the army, my nerves became seriously upset.

I reported to the barracks doctor who seemed quite alarmed and after a long, fruitless talk about my problems and the need for ‘facing-up’ and ‘pulling myself together’ he referred me to a psychiatrist.

The first one spent several hours discussing my early life and my schooldays and then, as is the way with doctors, he sought a second opinion. A third and fourth opinion followed and with remarkable unity they decided that I was a compulsive civilian and quite unfit for military service. I was no use to the army nor it to me, with which view I readily agreed.

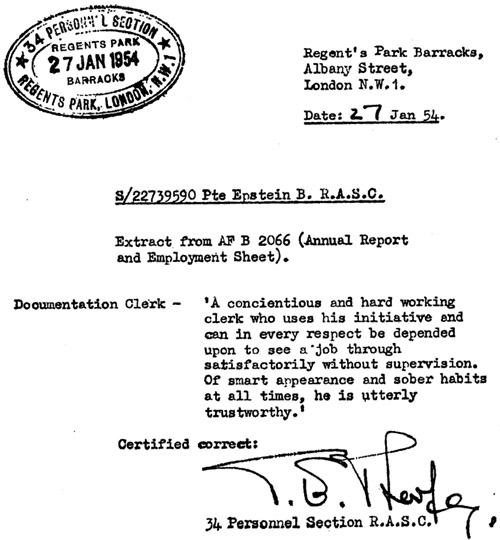

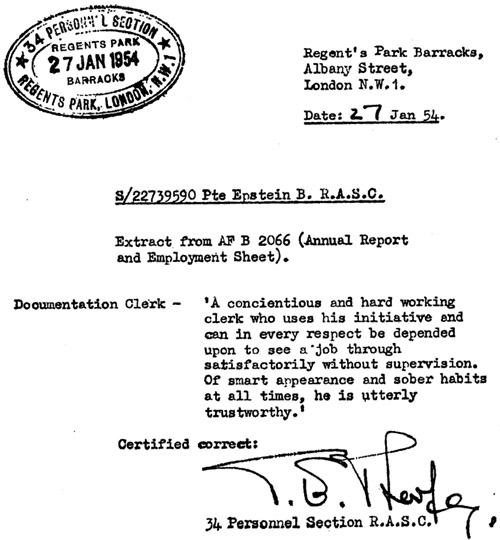

After less than twelve months as the most unsatisfactory private soldier in the Royal Army Service Corps, I was discharged on medical grounds though in that quaintly detached and benevolent way which sets the army aside from reality, I have a military reference which describes me as a sober, reliable and conscientious soldier.

I ran like a hare for the Euston train after handing in my hideous uniform and I arrived in Liverpool prepared to return, to my parents and Clive, as a junior executive anxious to work very hard.

They welcomed me generously though they were very worried about the discharge and to my great relief I felt instantly at home back in the furniture store in Walton.

There was, in the store, a tiny record department which I had helped to open and though I was not musical, I was interested in good music and I loved classical records.

I had, by now, passed my driving test at the fourth attempt. I had the use of a car, and was earning much more than £5, there was a good record department and there were to be no more interruptions from the drill sergeant at Aldershot. I was, I believed, nicely settled.

But … by night I was seeking escape in the cool and cultivated dusk of the front stalls of Liverpool Playhouse. This was, and always will be, a splendid repertory centre—the hothouse of Redgrave and Donat and Diana Wynyard in their beginning bloom. …

… And of Brian Bedford, the brilliant young medal-winner from RADA who had Liverpool reeling with his immense and powerful Hamlet.

Off-stage, Bedford and a few other young optimists formed a clique including actors and actresses, designers and writers. Plus a settled, soon-to-be-stolid furniture salesman from Walton called Epstein who began to feel rather old.

One night, in the Basnett bar—an extremely pleasant pub, long and narrow and with a marble counter; a stage-whisper away from the Playhouse—a gang of us were having a drink after the show. It was Saturday—the final night of a three-week run, and Helen Lindsay, a lovely actress now well known on television, had done very well in a difficult part.

There was a lot of praise and noise and everyone was very pleased with themselves in that disarmingly vain way nicer actors have. I suddenly felt depressed and I said: ‘I think I’ll pop off home, I’m rather tired.’

Brian bawled: ‘Nonsense. This is a wonderful night. We’re only just starting.’ I said: ‘You may be—all of you. I’m a doomed middle-aged businessman.’

Helen said: ‘What do you want to do with your life?’ and I replied, to my immense surprise, ‘I wouldn’t mind being an actor. But it’s too late.’ Brian refused to accept this and said: ‘There’s a very good chance you could get into RADA.’

He had, of course, distinguished himself there and he and Helen encouraged me to seek an audition. I was to travel to London to meet the then Director, John Fernald. A few weeks later I arrived in London and, at the Academy, I met Fernald—a former Liverpool Playhouse Director—and performed two pieces for him. A short reading from Eliot’s Confidential Clerk, and another from Macbeth.

I thought they were not particularly well done but Fernald, an agreeable and able man, said: ‘That was not at all bad. Would you like, presuming you are suitable, to start next term?’

I liked very much and once again I left my tables and chairs in Walton and set off South. My parents, who had been forced to accept the interruption of the army, were very unhappy about the latest break in my career. They believed that becoming an actor was only a shade better than my boyhood dreams of dress-designing. It was unstable and, like dress-designing, unmanly; there was no money in it. And who was to take over the family business? But their wonderful regard for my personal happiness persuaded them to let me become an actor.

Thus, at twenty-two, though already a secure and fairly successful business man, I submitted myself once again to the discipline of community life. I became a student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and dreamed of stardom and great fame.

RADA at that time was producing the young players who formed the new wave in the British theatre. O’Toole and Finney, Susannah Yorke and Joanna Dunham. Joanna was in my class and she was one of the few people at RADA who made life bearable, for within a few weeks I grew to loathe the place and the other students, and I was, yet again, face to face with failure.

I stuck it three terms and discovered a distaste for the actor-type which lingers even now. The narcissism appalled me and the detachment of the actor from other people and their problems, left me quite amazed.

An actor is not the least interested in anyone else. He seeks the friendship of those in the business who have succeeded and those outside who can help him. He fears failure with an awful intensity and he will never associate with anyone who has failed in case he himself becomes contaminated. There are exceptions but they are few.

I think my disenchantment with the acting profession became total when I spent a fortnight in Stratford with the Royal Shakespeare people. They were really frightful, and I believe that nowhere could one discover such phoney relationships nor witness hypocrisy practised on so grand a scale, almost as an art.

So, after the end of my third term at RADA, I returned home for the vacation nursing a secret decision never to leave home again and hiding a sense of inadequacy which was almost complete. Was there, I wondered, no job I could stick for longer than a year?

The vacation over, I was due to start my fourth term. My parents took me for a farewell dinner to the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool and asked me, purely as a matter of ritual: ‘Are you quite sure you want to go back?’

‘I don’t want to,’ I said. ‘I want to stay here. I should like to come back into the business if I can.’