IN the intervening days I sold over 100 copies of ‘My Bonnie’ and after the initial success, sales snowballed and the record went quite well for a first effort in a provincial city.

December 3rd arrived but at 4.30 p.m. there were only three Beatles. Paul was the missing one and after half an hour of listless conversation—for it was pointless to talk any sort of terms with only three of them—I asked George to ring Paul and find out why he was late.

George returned from the ’phone with a half smile which annoyed me a little and said ‘Paul’s just got up and he is having a bath’. I said ‘This is disgraceful, he’s very late’, and George, with his slow, lop-sided smile said ‘and very clean’. Paul arrived an hour later and we all went to a milk bar. We had a coffee each and I found that they had no management—or guidance beyond their instincts—those uncanny instincts on which I now rely so much.

They were very respectful to me but I didn’t know whether this was because I had money, a car, and a record shop, or whether it was because they liked me. I suspect it was a little of both.

Just for the camera. Brian

and double bass. He plays

not a note, neither reads nor

writes music. But then … neither

do the Beatles.

The five of us discussed, in vague terms, contracts and their futures, but of course none of us knew anything about the right terms or the prices for their sort of act.

We left the milk bar with nothing decided except that we would have another meeting the following Wednesday and in the meantime I went to see a Liverpool lawyer friend, Rex Makin to discuss management and to try to share some of my excitement about the Beatles. Makin, who had known me well for years, said ‘Oh, yes, another Epstein idea. How long before you lose interest in this one?’ A justifiable comment but one which offended me because I felt strongly and irrationally that I was going to be permanently involved with the Beatles.

One of my earliest feelings about their work was that they were so badly paid. They earned 75/- each per night at the Cavern and that was above the normal rate and was, in fact, more than Ray McFall need have paid them. I found later that he had insisted on increasing their pay because he too felt there was more than ordinary talent there, and consequently greater drawing power for him at the Cavern.

I believe very strongly in the rewarding of ability and I hoped that even if I were not to run their affairs completely I could at least secure a decent rate for their performances. But first I had to be sure that they were reliable people. I asked around the Cavern about them and tried to form a picture of them—of their reputation, their reliability and so on.

Not everyone to whom I spoke was in favour of these unruly lads who had thought more of their guitars than their G.C.E. and who had spent a lot of time in sinful Hamburg. One man, still a talkative colourful figure on the Liverpool Scene, was very direct. I was in a club in the city, called the Jacaranda talking about the upsurge beat music which had taken me so much by surprise, and I said to this man: ‘Do you know a group called The Beatles?’

‘Do I? Listen Brian,’ he said, ‘I know the Beatles very well indeed. Too well. My advice to you—and I know something about the pop world—is to have nothing to do with them. They will let you down.’

He was more wrong than anyone will ever know. For not only have the Beatles never let me down, or anyone else down since I met them, they have always done far more than their contracts demanded and would have been hurt if some things had been written into their contracts. They, like me, prefer some things to be taken on trust.

On the Wednesday before I again asked them to come to the shop, it was early closing, and I met them outside the door in Whitechapel and led them in. I looked at them all slowly and said: ‘Quite simply, you need a manager. Would you like me to do it?’ No one spoke for a moment or two and then John, in a low husky voice, blurted: ‘Yes.’

The others nodded. Paul gazing in that disturbingly wide-eyed way asked ‘Will it make much difference to us? I mean it won’t make any difference to the way we play.’

‘Course it won’t. I’m very pleased anyway’ I said without the slightest idea of the disappointments ahead before I could contemplate taking a penny in manager’s fees. I started with the Beatles as I have with all my artistes—running them at a loss until they earn enough to afford to lose a percentage.

We all sat and looked at one another for a moment or two, none of us really knowing what to say next. Then John broke the silence: ‘Right then Brian. Manage us, now. Where’s the contract? I’ll sign it.’

I had no idea what a contract even looked like and I didn’t think it would be sensible to take the signatures of four teenagers on any old piece of paper. So I sent away for a sample contract and produced it at our next meeting on the following Sunday at The Casbah, a beat club at the home of Pete Best, then, of course, the Beatles’ drummer.

The contract had been drawn up by people who knew more about a fast buck than does a slow doe. I thought it an inhuman document providing simply for the enslavement of any artiste eager and gullible enough to place his name over a stamp. Its like is still around and there are several artistes, some of them quite well-known, bound by this form of contract. I am not permitted to name them but they and their owners know who are they.

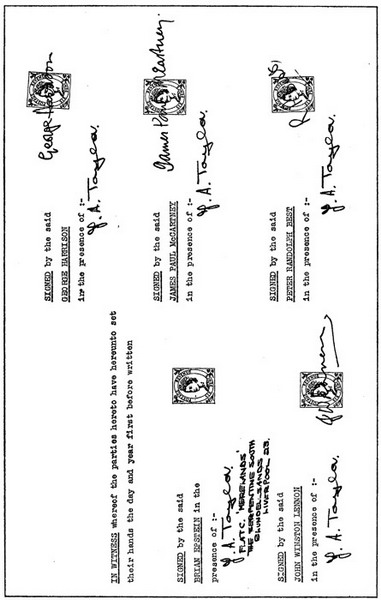

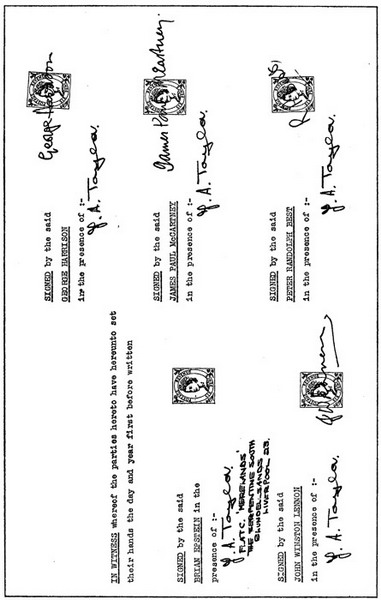

However, using it as a guide for wording and by modifying and adapting the terms, we eventually drew up a Beatles-Epstein agreement which each Beatle signed in the presence of Alastair Taylor, then employed in the shop, now Nems’s General Manager. One signature was never placed on that first contract. Mine. But I abided by the terms and no one worried.

I felt that having now to guide the career of these four trusting boys, I should make it a priority matter to persuade a recording executive to hear them sing and play. I wanted someone from one of the big companies, preferably Decca, because I had better personal contacts with the sales people there.

Mike Smith of Decca came to the Cavern in December 1961, and caused a tremendous stir. What an occasion! An A. & R. (Artistes and Repertoire) manager at the Cavern!

I had approached him through a Liverpool representative of Decca, and I found him very helpful and friendly. We had dinner and at the Cavern he was ‘knocked out’ by the Beatles. He thought that they were tremendous and this made me very elated because he was at the centre of the music business and his word, I thought therefore, carried authority.

I said nothing to the Boys about this at first because I wanted to calm down, but when I did tell them they became very excited and we all felt more confident. Wanting to behave like a Manager I approached Ray McFall and said ‘How about more bookings for the Beatles?’

He said he would do what he could, and I was very proud when Bob Wooler came to me one day and asked ‘What are the Beatles doing on Sunday?’ I reached for my diary and said: ‘They may be busy but I will try and fit you in.’ This, at last, was being a Manager and I remember the occasion vividly.

The big groups in Liverpool in those days were The Undertakers, Johnny Sandon and The Searchers, Rory Storme and the Hurricanes (this group had a drummer called Ringo), The Remo Four, The Four Jays (later to be known as the Fourmost), The Big Three and the very promising Gerry and the Pacemakers. I was sure that the Beatles would leave many of them behind in a very short time.

Mike Smith agreed, and we secured them an audition at Decca on New Year’s Day 1962. They came to London and stayed at the Royal Hotel, paying 27/- a night for bed and breakfast in Woburn Place. They were poor and I wasn’t rich but we all celebrated with Rum and with Scotch and Coke which was becoming a Beatle drink.

We were gently excited—although we knew that a recording test was only the beginning. We knew also—from the boys’ experience in Hamburg, from mine in the retail trade—that of the hundreds of songs which are sifted from the tens of thousands submitted, only a few score would become hits.

And we were not even on tape with our songs!

I said to the boys the following morning: ‘What if the whole things collapses? There’s no guarantee we can get near a contract yet. Will you be very disappointed?’ They all said: ‘No.’ But their faces said ‘Yes’ and I realized that I had been building up ridiculously high hopes on the recording test.

At 11 a.m. on January ist we arrived at Decca in a thin bleak wind, with snow and ice afoot. Mike Smith was late and we were pretty annoyed about the delay. Not only because we were anxious to tape some songs but because we felt we were being treated as people who didn’t matter.

We taped several numbers and then returned to Liverpool to wait. I returned to Decca again in March, on invitation for a lunch appointment. I felt pessimistic but tried not to show it when I met Beecher Stevens and Dick Rowe, two important executives. We had coffee, and Mr. Rowe a short plump man said to me: ‘Not to mince words Mr. Epstein, we don’t like your boys’ sound. Groups of guitarists are on the way out.’

I said—masking the cold disappointment which had spread over me: ‘You must be out of your mind. These boys are going to explode. I am completely confident that one day they will be bigger than Elvis Presley.’