JOHN.… Paul.… George. And Ringo. Collectively the four most famous names in the world. Extraordinary young men who have directly altered the lives of hundreds, even thousands of people, who have affected the entire balance of the entertainment industry, who have kicked up so much dust that in all our lifetimes, it will not completely settle.

They are daily conversation in hundreds of millions of homes throughout the world. More has been written about them than about any other entertainer of any era. The haunted, wonderful wistful eyes of little Ringo Starr from Liverpool’s Dingle are more instantly recognizable than any single feature of any of the world’s great statesmen.

The superlatives of the industry in which they belong, though gross and wild and overstated, cannot begin to describe the impact of four young men in their early twenties, who left school before they should, who can neither read music nor write it, who care not a fig or a damn or a button for anyone save a tight, close-guarded clique of less than a dozen.

For John, Paul, George and Ringo are themselves the ultimate superlative. They have defied analysis though not for a year or two has there been a shortage of analysists prepared to devote an amazing amount of time to delving, scratching and soul-baring to look for a reason for the inhuman grip of the Beatles.

I have known them so long, so well and with such personal involvement that I rarely try to examine what has happened or why. I was there when the foursome was born—when the face of Ringo slotted into the curious chemical pattern and thus created the four-constituent formula which has driven the young womanhood of the world into a demented frenzy of exultation, and admiration.

Yet I cannot pretend that, facially, Ringo seemed to me to be the perfect fit. And certainly the other three did not band together originally because they knew that somehow they were to become a hypnotic blend. George and Paul and John linked up simply because there were three teenagers keen on making music and because they could do it without rowing or arguing over small things.

In other words they got on well together, and when the disappearance of Pete Best left them without a drummer, they asked for Ringo because he could do the job and because they liked him.

But. … But it is inescapable that Ringo was the catalyst for the others. He certainly completed the jigsaw and the Beatles with Ringo became a magnet for the great camera-artists of the world, a target for the jaded lately-hostile eyes of people who had hardly known that popular music existed.

I am not here discussing their music at all, though, of course, it was and is this which is the core and reality of their success and the Beatles themselves would not give a fragment of a moment’s thoughts to anything as obstruse as chemical appeal or collective magnetism. But I believe that there is something a little outside our normal experience in the Happening of the Beatles and I believe it is valuable to make the point. It may be magic or it may be some strange organic combination. Whatever it is, it is there and it goes far beyond ‘Twist and Shout’ or ‘She Loves You’.

There was, of course, another famous foursome—though in fiction—and, strangely, they started as a threesome and only realized complete fulfilment when the fourth was added. They were Athos, Porthos, Aramis—and D’Artagnan. They were slightly outside society, yet socially acceptable, non-conformist but in no way outlawed.

This, in essence, is the Beatles. They are British, but un-English in that they accept barriers neither of class nor sex. And for this all classes and both sexes adore them. They are of Liverpool with its hard, flat humour, but they have a far wider, more way-out private world of inward smiles than the average earthy Liverpudlian. They are pop-stars with little respect for the specious values of the industry.

The Beatles don’t say ‘Glad to meet you,’ but they often are. They don’t flatter women but they never sit while a woman stands. They have their own rules and one may not understand them but they are workable, and they have never damaged anyone outside which is more than one can say for some of Society’s rules.

I am always being asked: ‘What are the Beatles really like?’ I never know quite what to say because they are what they are and anyone who has ever seen or heard them either in person, or on radio or screen has, basically, as much chance as I have of knowing what they are like. I believe, and I must say it, that they are quite magnificent human beings, utterly honest, often irritating but splendid citizens shining in a fairly ordinary, not very pleasing world.

In many ways they are the same now as they were when I first met them. Immeasurably richer of course, with a rounder confidence and a rational consciousness of their status in the hierarchy of popular music, but they have not become arrogant and they never will.

Much nonsense has been written of the Liverpool Sound, as if it were some instantly recognizable package-deal in electronic music. Of course, it is no such thing. There is, for instance, no common sound linking the Beatles with the Searchers, or Billy J. Kramer with the Fourmost. And Gerry and the Pacemakers are like none of these.

What there is between all these groups is their origin as Liverpudlians and it is this basic take-everything-in-your-stride provincialism, born of life in a raw seaport on the edge of England, which sustains them in the face of their incalculable fame and international adulation. At the centre of the storm which has surrounded them for nearly two years the Beatles are very calm. They have somehow found a little island where the gale of press and public becomes a mild and gentle breeze which leaves them rich and contented but undamaged.

I have no favourites among the Beatles and this they realize now but it wasn’t always so. A manager dealing with a close-knit foursome has to be as fair as and as cautious as a father of four children. And one night very early in my management of the Beatles this was brought home to me with an unpleasant thump.

In the long ago days of 1962 the Beatles had a van for their equipment which on occasions was also used to transport them. But whenever I could I would drive to each of the Beatles’ homes and collect them for a show. This particular night I called on John first then on George and then on Paul—Peter Best was travelling in the van.

George got out of the car and knocked on Paul’s door in the little street where he lived in Allerton. He knocked for a few moments and there was still no sign of Paul. Finally Paul answered and said, ‘Tell Brian I’m not ready and I’ll be a while.’ George came back to the car and told me this. I said: ‘Well he should be ready. I said I’d be here at eight and it’s past eight.’ George went back to the house, returned a minute later and said Paul still was not ready. I said: ‘George, tell him we’re going to the Beehive for a drink and if he likes he can get the bus to the city centre, the train to Birkenhead and another bus to the Technical College’

It was a very important evening because we were making money at last and the Technical College show was a good one, in a good hall, and was completing an otherwise successful three part engagement for Liverpool University. Also we had another concert much later that night at New Brighton Tower. We went to the Beehive pub and from there one of the Beatles telephoned Paul. I believe it was John. He came back from the ‘phone and said: ‘Paul now says he’s not coming. He’s very annoyed at having to get the train and the bus.’

I was worried, angry and upset and I toyed with the idea of telling Paul that I would not be bothered with managing the Beatles if this was the way they were going to behave.

I went into Nems Office to telephone Paul and the other Beatles went home. I spoke to his father—a Very charming and gentle person—who said Paul was upset and would not be able to attend the shows. Paul, however, relented much later, we gathered the other Beatles and we rushed to New Brighton Tower where we were able to catch up and give the University concert.

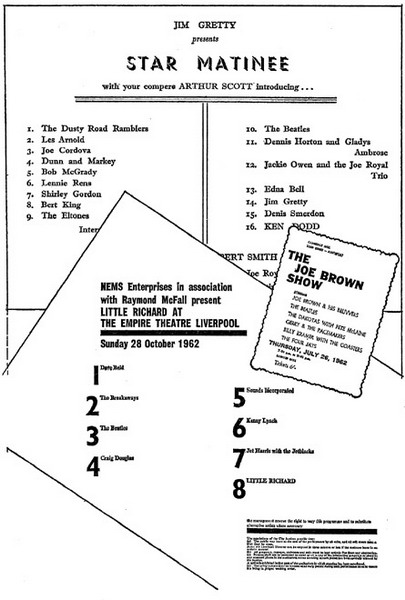

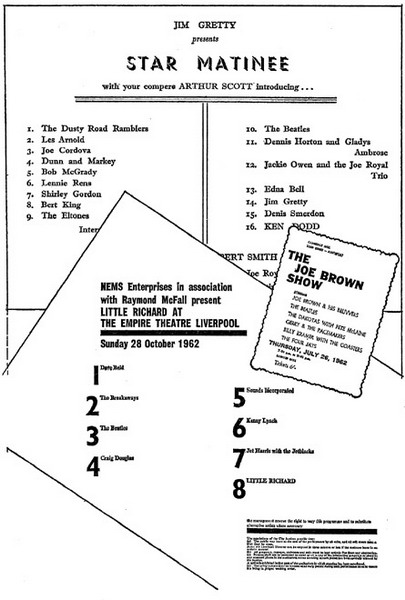

In the beginning … some early Beatle programmes

This was the only time any one of the Beatles refused to play and it could never happen now. But it was not the only time one or more of the Beatles fell out with me. It would not be normal or reasonable to expect four artistic men to glide through life without a clash of views and although rows are rare, they happen.

Paul can be temperamental and moody and difficult to deal with but I know him very well and he me. This means that we compromise on our clash of personalities. He is a great one for not wishing to hear about things and if he doesn’t want to know he switches himself off, settles down in a chair, puts one booted foot across his knee and pretends to read a newspaper, having consciously made his face an impassive mask.

But he has enormous talent and inside he has a great tenderness and great feeling which are sometimes concealed by an angry exterior. I believe that he is the most obviously charming Beatle with strangers, autograph hunters, fans and other artistes. He has a magnificent smile and an eagerness both of which he uses, not for effect, but because he knows they are assets which will bring happiness to those around him.

Paul is very much a world star, very musical with a voice more melodic than John’s and therefore more commercially acceptable. Also, and this is vital to me, he has great loyalty to the other Beatles and to the organization around him. Therefore, I ignore his moods and hold him in high esteem.

I would not care to lose him as a friend.

John Lennon, his friend from boyhood, his co-writer of so many songs, the dominant figure in a group which is, virtually, without a leader, is in my opinion, a most exceptional man. Had there been no Beatles and no Epstein participation, John would have emerged from the mass of the population as a man to reckon with. He may not have been a singer or a guitarist, a writer or a painter, but he would most certainly have been a Something. You cannot contain a talent like this. There is in the set of his head a controlled aggression which demands respect.

David Ash, a feature-writer on the Daily Express once described this face: ‘… it has the fear neither-God-norman quality of a Renaissance painter’s aristocrat. …’

Beautifully put and I don’t think this will be bettered, though, like the other Beatles, John would regard this sort of description as soft, stupid. They are wary of overstatements, chiefly because they are surrounded and swamped by it, not only from fans but from essential hard-sell vocabulary of the showbusiness world.

Who writes the words and who the music? So people ask endlessly. The answer is that both write both and that sometimes John will do a song completely by himself, words and music and that sometimes Paul will arrive with a completed number. But neat and tidy and honest though John’s lyrics are, they represent only a fraction of his real aptitude for words.

For John, the pop-singer from Liverpool, was guest of honour at a Foyle’s lunch to mark the success of his splendid book: John Lennon in his own Write, an extraordinary collection of verse, prose, and drawings, done by him off-the-cuff, without training or guidance. It sold more than 100,000 copies in Britain, topped the best seller list and was marvellously well-reviewed.

I was not the least bit surprised but I was deeply gratified that a Beatle could detach himself completely from Beatleism and create such impact as an author.

And made no speech.

In answer to the toast he stood, held the microphone, and said: ‘Thank you all very much. You’ve got a lucky face.’ Sir Alan Herbert, who was sitting beside me, said later: ‘A shameful affair, he should most certainly have made a speech.’

But here John was behaving like a Beatle. He was not prepared to do something which was not only unnatural to him, but also something he might have done badly. He was not going to fail. After the luncheon he commented: ‘Give me another fifteen years, I might make a speech. Not yet.’ And I agreed with him. I rely on John’s instinct and, in fact, on the instinct of all the Beatles, not only on music, but in matters of taste and style and general behaviour.

I believe I always knew that I was dealing with people who were not just a pop group, but were exceptional human beings. John’s wit and flair were apparent when I first met him and his old-young bearing was obviously right for public appearances.

None of the Beatles suffer fools gladly. John suffers them not at all and can be very acid, even cruel, if he is goaded. A silly woman approached him in Paris, peered into his face and said: ‘It isn’t! It is. Is it? It’s you. A real live Beatle!’

John stared at her, his lids hooding his eyes, ‘What sort of an approach is this,’ he asked and he did a wild, terrifying dervish dance around her. Frightened out of her life, the lady fled down the corridor of the George V hotel and never again I suspect will she peer into the face of a Beatle, as if she is in a zoo.

At the Foyle’s lunch, when John was besieged by a great many fighting middle-aged ladies who should have known better, one woman clutching ten copies of his book for autograph, said: ‘Put your name clearly just here,’ and she prodded a page with a grossly over-jewelled finger. John looked at her, astonished, and she turned to a friend jammed against her and said: ‘I never thought I would stoop to asking for such an autograph.’ ‘And I never thought,’ remarked John, ‘that I would be forced to sign my name for someone like you.’

Sometimes he has been abominably rude to me. I remember once attending a recording session at E.M.I. studios in St. John’s Wood. The Beatles were on the studio floor and I was with their recording manager George Martin in the control room. The intercom was on and I remarked that there was some sort of flaw in Paul’s voice in the number ‘Till there was you’.

John heard it and bellowed back: ‘We’ll make the record. You just go on counting your percentages.’ And he meant it. I was terribly annoyed and hurt because it was in front of all the recording staff and the rest of the Beatles. We all looked at one another and felt uncomfortable and John turned away, indicating that there was no apology coming. I left the studios in a sort of sullen rage.

Later we had it out, but he told me quite emphatically that it was not cruelly intended and only meant in fun. He is a full and generous person and I cannot think of anyone I admire or like better.

Ringo Starr, last to become a Beatle, came into the group not because I wanted him but because the boys did. To be completely honest, I was not at all keen to have him. I thought his drumming rather loud and his appearance unimpressive and I could not see why he was important to the Beatles. But again I trusted their instincts and I am grateful now. He has become an excellent Beatle and a devoted friend. He is warm and wry-witted, a good drummer, and I like him enormously. He is a very uncomplicated, very nice young man.

We rarely fall out because he, probably more than the others, is amenable to most suggestions. Yet there was one unpleasant incident at the start of the Paris trip early this year.

It was January and the Beatles were due to tackle a country in which—compared to, say, Scandinavia or Germany, they were an unknown quantity. Therefore I was anxious to make a good initial impact. This can be achieved, and the U.S. trip proved it, at the arrival airport.

But fog descended over Liverpool and Ringo Starr could not leave for London to catch the connecting aircraft to Paris. The other Beatles and I and a score of journalists were in London when we heard the news. Naturally I was very disappointed that three Beatles instead of four would descend the steps at Le Bourget Airport in Paris. I telephoned Liverpool and asked Ringo to catch the train so that he could join up in Paris as soon as possible.

He refused, possibly because he believed that a Beatle shouldn’t travel by train, and said he would catch the first available plane. I didn’t want this because I didn’t trust the weather and I said so.

I said: ‘Ringo, I have never asked you to do anything especially for me before,’ and he replied: ‘Oh yes you have. You know bloody well you are always asking me to do things—to see the Press, or travel for this or that. I’m not doing it and if you don’t like it you can do the other thing.’

I was very angry and when, eventually, he arrived in Paris there was quite an atmosphere. But sulking has no place in a group like the Beatles and with just a couple of meaningful looks and a grin all was well. And, as with other difficulties, a frank talk helped. We get on extremely well and later this year, George and Ringo came to live in the same block of flats as I do.

George too has his moods though I cannot recall any particular row. I don’t enjoy arguments, nor do the Beatles so we avoid anything too contentious. George is remarkably easy to be with. He, like the others, has expanded as a person and though collectively—on first sight—they appear to behave alike, they have specific characteristics.

And George is the business Beatle. He is curious about money and wants to know how much is coming in and how and what best to do with it to make it work. He would like to invest. He is generous but shrewd. He enjoys spending but would always remain in credit. He likes cars, big and fast, but would be careful to secure a good trade-in price for his old one.

Strangers find him an easy conversationalist because he is a good listener and shows a genuine interest in the outside world. He wants to know and I find this an endearing trait in a young man who is so successful and so rich that if he never learned anything new he would not suffer any loss. And in addition to all these characteristics, he is, though not one of the prolific composers, very musicianly.

George takes enormous care with tuning before a show. He has a very fine ear for sound and for a delicate half-note and the others respect him for it. On stage he is the one who twiddles the tuning instruments and you can almost see his ears twitching to detect a faint discord.

Virtually, if Paul has the glamour, John the command, Ringo the little man’s quaintness, George with his slow, wide, crooked smile is the boy next door.

They are very fine extraordinary young men. I don’t believe anything like them will happen again, and I believe that happen is the word since no one could have created anything in show-business with such appeal and magnetism.