CHAPTER TWO

Licentious Rhymers

DONNE AND THE LATE ELIZABETHAN COUPLETR EVIVAL

TO MODERN READERS accustomed to encountering couplets in the poems of Dryden, Pope, and their imitators, the form seems to represent the Enlightenment in miniature. The relentless chime of the end rhymes and the perfect balance of the clauses seem tailor-made to transmit eighteenth-century views of rational judgment, discipline, and order.1 But the prominence of the balanced eighteenth-century couplet has obscured an earlier, more risqué reputation of the form. Prior to 1600, iambic pentameter couplets were disdained by sophisticated English poets, who associated the rhyme scheme with loose verse and libertine thought. Though in the early seventeenth century Ben Jonson and his literary progeny converted the pentameter couplet into a form congenial to neoclassical restraint and balance, sixteenth-century poets and critics connected couplets with The Canterbury Tales and with an outmoded kind of verse they deemed merry, light, and vulgar. In the mid-1590s, a group of boisterous young poets revived and reimagined the couplet precisely because of its reputation as an ancient and licentious form. Reacting against the elaborateness of Elizabethan stanzaic poetry, these poets took up the couplet in order to flout newly established poetic laws and return English poetry to its original state of liberty.

The couplet poets—Christopher Marlowe (1564–93), John Donne (1572–1631), Everard Guilpin (1572–?), Joseph Hall (1574–1656), John Marston (1576–1634), and Thomas Middleton (1580–1627)—belonged to what can be loosely described as a new school of poetry that arose in the 1590s. Most of the poets who belonged to this school were in their twenties, and many were students or residents at the Inns of Court. They defined themselves in opposition to contemporaries who saw Spenser and Sidney as their contemporary masters, who held up Virgil and Petrarch as their poetic forefathers, and who favored genres like pastoral and the sonnet. The couplet poets of the 1590s instead chose to imitate witty and urbane Roman poets like Horace, Ovid, Martial, and Juvenal. They tested the boundaries of erotic propriety in love elegies and epyllia and deflated the pretensions of polite society in satires and epigrams.2 And while their contemporaries preferred to write in stanzaic forms and interwoven rhyme schemes, the new poets chose to revive a form that had been used intermittently over the course of the previous century: iambic pentameter couplets.

Donne played a formative role in this late Elizabethan trend for writing in what Marlowe calls “looser lines.”3 In fact, Donne produced the largest and most varied body of couplet poetry in the 1590s. Donne’s status as a couplet poet has long been overlooked since the portion of his early corpus favored by twentieth-century readers, his “Songs and Sonnets,” consists largely of stanzaic poems.4 But nearly everything else Donne wrote in the 1590s—his elegies, satires, epigrams, and most of his verse letters—is in iambic pentameter couplets.5 Even in the “Songs and Sonnets,” where Donne rarely repeats a rhyme scheme, continuous couplets are by far the most frequently used verse form, occurring in eleven of fifty-five poems, including such well-known poems as “The Flea.” Moreover, the few records that remain of Elizabethan and Jacobean engagement with Donne’s verse indicate that early readers did not privilege the “Songs and Sonnets” as we do and that they may have actually preferred his couplet verse.

By considering Donne’s early experiments with the couplet, I aim to provide a new perspective on a period of Donne’s career that has often proved elusive for several reasons: the lack of surviving Elizabethan manuscripts of Donne’s verse, Donne’s reserve about his verse practice and poetic influences, and the diversity of personae and moral positions that he adopts in his early poetry. Attending to verse forms can shed new light on Donne’s youthful thought as well as the controversies that embroiled the Inns of Court in the 1590s because premodern poets and theorists did not isolate formal questions from social, political, and ethical concerns and, in fact, often endeavored to defend and recommend the art of poesy by attributing larger implications to formal features like rhyme and meter. They recognized that verse forms, like genres, carry considerable freight along with them and allow poets to associate themselves implicitly with particular figures and epochs in literary history. This chapter endeavors to reveal the larger stakes of Donne’s prosodic choices by responding to two questions: what prompted Donne and his youthful contemporaries to take up the iambic pentameter couplet in the 1590s, and how did they adapt it to their purposes?

Throughout this chapter, I have avoided using the term “heroic couplets,” which has forced me to use precise but at times tiresome formulations like “iambic pentameter couplets” and “decasyllabic couplets.” I have gone out of my way to avoid the familiar adjective not only because it is not an Elizabethan term but because prior to 1600 the decasyllabic couplet was anything but heroic. In the 1590s the phrase “heroical verse” was used to refer to ottava rima rather than couplets.6 Indeed, Elizabethans consistently associated decasyllabic couplets with The Canterbury Tales and other light and comic works produced by England’s “auncient rymers” (Arte, L1v).7 In their poetic manuals, theorists like George Gascoigne and George Puttenham accepted a late medieval distinction between couplets and stanzaic verse that depicted couplets as native, light, and unrefined and stanzaic forms as foreign, grave, and sophisticated.8 Disdain for the couplet stemmed from analogical readings of its formal features as well as from its association with outdated verse: because the Chaucerian couplet was often characterized by enjambment, loose placement of the caesura, and slant rhyme, strict poetic lawgivers like Puttenham rejected it as a licentious form beneath the dignity of a courtly artificer (Arte, L1v). The distinction between loose couplets and grave stanzas was not simply theoretical but reflected the practice of sixteenth-century poets. Before the rage for pentameter couplets in the 1590s, the form was used infrequently over the course of the century, but, when it was used, it was primarily for lighter fare like beast fables, romances, ballads, epigrams, and satires. Many of these works, like the couplet epigrams of Donne’s maternal grandfather, John Heywood, look back nostalgically to Chaucer’s age as a time when the English were bawdier but also more virtuous since they used wit and homespun wisdom to check the newfangled vices of civilized society.9

Donne and his contemporaries took up the form because of these associations with the light but upright verse of the ancient rhymers of England. Scorning the high level of artifice cultivated by their poetic elders and contemporaries as well as inveighing against the increasing sophistication of London life, the new poets frequently expressed their desire to return to a time before “free borne” men “disclaime[d] Natures manumission” and made “themselues bond to opinion.”10 This longing for an ancient state of liberty is a central preoccupation of the new poets and links the Stoic satires of Hall with the libertine erotic verse of Marlowe and Donne. All these poets look back to a more natural Saturnian age: in his first moral satire Hall mocks continental apparel and appeals to a time when “that homely Emperour” Saturn dressed with less pomp than a contemporary “vnder-groome of the Ostlerie,” and in a mythical digression within Hero and Leander Marlowe depicts Mercury and Cupid—figures of scholarship and love—conspiring to end Jove’s violent rule and return Saturn to his rightful seat.11 The turn toward the pentameter couplet was intertwined with this radical naturalism and disdain for fashionable artifice. Just as Elizabethan satirists mocked the imported apparel, the “far-fetched liuery,” of the fashionable London set, they often ridiculed interwoven stanzas as superfluous foreign finery.12 As Chapman put it in a colorful 1598 preface to Achilles Shield, “octaues, canzons, canzonets” and other such “fustian” forms were “affect[ed]” only by the “strooting lips” of “quidditicall Italianistes.”13 Thus, to reject the stanza was to liberate oneself from French and Italian poetical tyranny and return to “free-bred poesie.”14

It was also to overturn what they saw as an Elizabethan preference for form over reason. Because the open couplet does not require the poet to wrap up a thought or sentence within a prescribed number of lines, it is particularly conducive to lengthy arguments, extended comparisons, and dramatic speech. These are all, of course, characteristic features of Donne’s verse. I will make the case that Donne developed aspects of this characteristic and influential style by experimenting with the loose couplet in his early years as a student at the Inns of Court. Donne chose the couplet in the 1590s because it was associated with unpretentious poetry and liberty of thought. But his early apprenticeship to the couplet in turn shaped his style and his conception of poetic liberty in ways that would profoundly influence seventeenth-century poets like Jonson and Milton.

Auncient Rymers: Couplets in Elizabethan Poetic Theory

The term “couplet” did not become widespread until the seventeenth century, though it was first used to describe one of the shepherds’ poetical “sports” in Sidney’s Arcadia.15 Since no single term was settled on before 1600, poetic theorists used a delightful jumble of terms, including “distich,” “couple of verses,” “cooples,” “geminels,” “riding rhyme,” and, less concisely, “The verse . . . that consists of five feet, and the rhyme each verse immediately returned.”16 This inconsistency of vocabulary makes comments on the couplet difficult to locate in prefaces and poetic treatises. However, bringing together these scattered remarks reveals remarkable consistency in Elizabethan views of the verse form: whatever term theorists choose, they almost invariably connect the couplet to “our Mayster and Father Chaucer” and his imitators and associate it with light and bawdy narrative verse.17

George Gascoigne provides one of the earliest Elizabethan commentaries on couplets in his brief poetic handbook Certayne notes of Instruction, which was included in his 1575 collection of poetry The Posies of George Gascoigne, Esquire. At the conclusion of his treatise, Gascoigne offers guidance about how to choose among the “sundrie sortes of verses which we vse now adayes” by tracing their historical genealogies and noting the generic associations of each “kinde of ryme.” On the final page of the book, Gascoigne suddenly remembers that he left something out: “I had forgotten a notable kinde of ryme, called ryding rime, and that is suche as our Mayster and Father Chaucer vsed in his Canterburie tales, and in diuers other delectable and light enterprises.” After further apology for bringing in this “remembrance somewhat out of order,” Gascoigne goes on to say that “this riding rime serueth most aptly to wryte a merie tale” while another Chaucerian verse form, “Rythme royall,” is “fittest for a graue discourse.” Gascoigne desires to provide clear-cut “Notes of Instruction” for prospective English poets, so he attempts to use historical precedent to establish a fundamental rule that correlates certain “sorts of verse” with certain “enterprises.” Since Chaucer is the “Mayster and Father” of English poetry, the prosodic divisions within his corpus become prescriptive for all subsequent versifiers.18

This association of the short couplet with light verse was not simply a retrospective invention of Gascoigne. Traces of the distinction between light couplets and grave stanzas can be found in the works of Middle English poets. Chaucer apologizes for his octosyllabic couplets in his early poem House of Fame, remarking in the invocation to the third book that his “rym ys lyght and lewed” since he did no “diligence” to show “craft” but only “sentence.”19 The social implications of Chaucer’s description of his verse as “lewed”—that is, unlearned, unskillful, and low—become more apparent when it is read alongside a more extended discussion of rhyme in the verse prologue to Robert Mannyng’s fourteenth-century chronicle The Story of England (c. 1338). Mannyng relates that he was advised “many a tyme” to “turn” his story “in light[e] ryme,” that is, in four-beat couplets, because this form is “lightest in mannes mouthe” and most manageable for “lewed men” and the “comonalte.”20 If he had instead chosen to “turne” the poem “in strange ryme” and “in baston,” that is, in a French stanzaic form like “ryme couwee” (tail rhyme) or “enterlace,” the common performer and listener would have been utterly “fordon.”21 On the one hand, Mannyng associates the stanza with the educated and refined classes and with a “strange” or foreign poetic craft advanced enough to have complex terms of art, while on the other he connects the couplet with simple and intelligible native verse that provides “solace” for his common “felawes.”22 Mannyng’s belief that interwoven rhyme is too demanding for untrained ears is curious and makes one wonder how exactly he thought rhyme at a distance would confound a lewd listener, but it is clear that Mannyng prefers widespread comprehension of his “story of Inglande” to recognition for his prosodic dexterity and that he, like Chaucer, considers the short couplet to be the most appropriate form for those who prefer sentence to craft.23

Two hundred and fifty years later, Elizabethan theorist George Puttenham would draw on this distinction and its social implications in order to uphold the artful stanza over the common couplet. In the brief history of English verse he provides in book 1, Puttenham, like Gascoigne, distinguishes between the “graue and stately” rhyme royal “staffe” of Troilus and Criseyde and the “verse of the Canterbury tales,” which he calls, with patent disapproval, “but riding ryme” (Arte, I1v). He reveals the source of his disdain in his analysis of rhyme schemes, where he argues, in the vein of Mannyng, that rhyme at a distance is better accommodated to the “learned and delicate eare” while short couplet verse is more fitting for the “rude and popular eare” (Arte, M2r).24 Puttenham attempts to establish a quantitative rule for determining the lightness of a form: the more “speedily” the rhyme “return[s],” the lighter and more vulgar the poem (Arte, M1v–M2r).

Because the purpose of Puttenham’s book is to show that English verse can be just as refined and artful as Greek and Latin verse, he becomes exercised about the vulgarity and licentiousness of the “too speedy returne” of rhyme (Arte, M1r). In a colorful and revealing rant, he suggests that such verse is only fitting for

small & popular Musickes song by these Cantabanqui vpon benches and barrels heads where they haue none other audience then boys or countrey fellowes that passe by them in the streete, or else by blind harpers or such like tauerne minstrels that giue a fit of mirth for a groat, & their matters being for the most part stories of old time, as the tale of Sir Topas, the reportes of Beuis of Southampton, Guy of Warwicke, Adam Bell, and Clymme of the Clough & such other old Romances or historicall rimes, made purposely for recreation of the common people at Christmasse diners & brideales, and in tauernes & alehouses and such other places of base resort, also they be vsed in Carols and rounds and such light or lasciuious Poemes, which are commonly more commodiously vttered by these buffons or vices in playes then by any other person. Such were the rimes of Skelton (vsurping the name of a Poet Laureat) being in deede but a rude rayling rimer & all his doings ridiculous, he vsed both short distaunces and short measures pleasing onely the popular eare: in our courtly maker we banish them vtterly. (Arte, M1r)

In his harangue against short distances between rhymes, Puttenham manages to paint a vivid picture of what a more sympathetic or sentimental observer might have called “merry old England”: a world of taverns, minstrels, tales of old times, Christmas dinners, weddings, and bawdy songs.25 Puttenham’s rant sounds excessively vehement and has the ring of an aspiring gentleman trying to dissociate himself from his rude country relatives. If the English are to prove that they are “nothing inferiour to the French or Italian for copie of language, subtiltie of deuice, good method and proportion in any forme of poeme,” they must rid themselves of all the trappings of their unsophisticated past (Arte, H8v). In banishing the too speedy return of rhyme, Puttenham attempts to banish a whole vision of England that he thinks has prevented his country from producing a refined courtly maker.

Puttenham has disdain not only for the “vulgar proportion” used in The Canterbury Tales but also for the continuous and enjambed character of its riding rhyme (Arte, M2r). When he complains that “our auncient rymers, as Chaucer, Lydgate & others” do not keep the caesura “precisely” or mind the end of the line, his condemnation takes on a moral tinge (Arte, L1v). In letting “their rymes runne out at length,” these ancient poets ignore a “law” and “rule of restraint” intended to “correct the licentiousnesse of rymers” (Arte, L1v). Puttenham disparages rhymers so reckless that they “will be tyed to no rules at all, but range as [they] list” (Arte, L1v). They may manage to express themselves, to “vtter what [they] will,” but their work is undeserving of the lofty name of poetry and should be labelled “ryme dogrell” (Arte, L1v, L2r). Although Gascoigne and Mannyng establish a hierarchy of “light” and “grave” verse, for them the distinction is largely a question of fitness and knowing one’s audience. For Puttenham, the choice between enjambed couplets and end-stopped entertangle rhyme becomes a serious aesthetic and even moral question—to write in riding rhyme is not simply light and merry but vulgar, loose, and licentious. By failing to uphold the rules of measure and number, the licentious rhymer forsakes his primary responsibility as an Orphic poet, which, according to Puttenham, is to act as a “lawgiver” and “hold and containe the people in order and duety by force of good and wholesome lawes” (Arte, M2r). Since “proportion poetical” not only reflects cosmic order but produces social order, Puttenham fears that the result of stylistic licentiousness would be nothing less than moral decay and social chaos (Arte, K1r).

“Let my lines in freedome goe”: Discursive Couplets in Elizabethan Satire

George Puttenham was buried at St. Bride’s, Fleet Street, in London on January 6, 1591, less than two years after the anonymous publication of The Arte of English Poesie, so he did not live to see the rise of the new school of poetry in the final decade of the sixteenth century.26 But it is not difficult to imagine what Puttenham would have thought of the new poets since every complaint that he lodges against Chaucer and the ancient rhymers also applies to Donne and his fellows. In addition to breaking Puttenham’s law against speedily returning rhymes, they heavily enjamb their lines, place the internal caesura loosely, and use an inordinate number of feminine and slant rhymes. For the most part, the young couplet poets silently break the rules of refined poetry without announcing the reasons for their mutiny, but the satires of Donne’s peers Hall and Marston contain a wealth of information on style and prosody that illuminates the poetic program of this new school. In their poems on Elizabethan poetic trends, Hall and Marston indicate that their loose couplet style is intimately connected with the central goal of their satires: liberating Elizabethan society from the tyranny of fashion and opinion. They depict their rejection of the stanza and turn to the couplet as a deliberate effort to overturn the artificial rules of courtly makers and return English poetry to a natural state of liberty.

Though his satires were written later than those of Hall and Donne, John Marston is the most explicit about his poetic intentions and offers a manifesto of sorts for the couplet poets in his poem “Ad Rithmum.” While Puttenham despises the rhymer who “will be tyed to no rules at all, but range as he list,” Marston declares that he would prefer to “freely range” rather than “wrest some forced rime” (Arte, L1v; Scourge, E2r). He exemplifies his licentiousness even as he proclaims it, breaking nearly every Puttenhamic law in the space of three lines:

Then hence base ballad stuffe, my poetrie

Disclaimes you quite, for know my libertie

Scornes riming lawes. (Scourge, E1r)

To name just a few transgressions, the clauses recklessly overflow the line endings, and both final nouns are polysyllabic and would be classified by Puttenham as dactyls.27 Indeed, Puttenham argues that although “libertie” may not be a “precise Dactil by the Latine rule,” it will “passe wel inough” for a dactyl in “our vulgar meeters” because it is “usually vulgarly pronounced” as one (Arte, P2v). He warns against such polysyllabic and dactylic line endings, which, like the couplet, he associates with vulgar rhymes: they “make your musicke too light and of no solemn grauitie” and “smatch more of the school of common players than of any delicate Poet Lyricke or Elegiacke” (Arte, M2r). Marston has little regard for such courtly delicacy. Instead, he proudly describes himself as a poetic bull in a china shop in a passage that Ben Jonson would repeatedly mock:28

I cannot hold, I cannot I indure

To view a big womb’d foggie clowde immure

The radiant tresses of the quickening sunne.

Let Custards quake, my rage must freely runne. (Scourge, B8v)

The custard is a fitting emblem not only of courtly refinement—Dekker describes it as a pastry “stiffe with curious art”—but of the instability of such artifices: the truth-disclosing rage of the poet makes the egg-based delicacy quiver and quake.29 Marston’s verse is certainly wilder than that of Hall or Donne, but in his custard-quaking declaration of liberty, he simply amplifies the central concern of all late Elizabethan satires. The satirists of the 1590s aimed to expose the ways that their contemporaries had made themselves slaves to a host of unnatural masters: to Petrarchan mistresses and abject sensuality, to moneylenders and patrons, and, above all, to fashion and the conventions of polite society. It is striking how infrequently the satirists use metaphors of looseness or laxness to describe the vices and follies of the times. Instead, all the sins of London society are depicted as forms of restriction and “servile service” (Scourge, C2r). In fact, Marston uses a recurring rhyme to set up an antithesis between all kinds of “controule” and the free and rational “soule.” He repeats the pair so frequently that it becomes a kind of refrain or motto for the satire book as a whole:

But yee diuiner wits, celestiall soules,

Whose free-borne mindes no kennel thought cont[r]oules . . . (Scourge, B3r)

But as for me, my vexed thoughtfull soule,

Takes pleasure, in displeasing sharp controule. (Scourge, B5r)

O that the boundlesse power of the soule

Should be subiected to such base controule! (Scourge, G2r)30

The adjectives Marston uses to describe the human soul in these refrains—“celestiall,” “free-borne,” “thoughtful,” and “boundlesse”—hint at the philosophical underpinning of his belief that all vices are forms of slavery.

He explains his position in more detail in a passage that seems to have been accidentally left out of the 1598 edition of Scourge of Villanie but that was restored in the 1599 edition. The restored lines, addressed to “Gallants,” argue that we all have a “part not subiect to mortality” that is given “wings” by “Boundlesse discursive apprehension.”31 This immortal part “should grudge & inly scorne to be made slave” to humors within and masters without and “should murmur, when you stop his course.”32 Belief in a rational, immortal part of the soul was common in the period, but Marston’s depiction of reason as a wandering, boundless faculty and his suggestion that virtue is a result of releasing the soul from all stops and limits is less conventional. The passage is one of the most philosophical and argumentative in Marston’s work, and, not coincidentally, it is also one of the most enjambed: in the fourteen-line passage, the end of the sentence corresponds with the end of the line only twice. With his swift, overflowing lines, Marston reproduces the activity of his boundless discursive apprehension.

In fact, Marston’s multivalent adjective “discursive” captures many facets of the couplet poets’ characteristic style. Derived from the Latin verb discurrere, to run off in different directions, it means (1) expansive or digressive, (2) related to speech or discourse, and (3) characterized by reasoned argument or thought.33 The stylistic tendencies of Marston and Donne, particularly their tendency to imitate familiar speech and to let arguments and conceits run their full course, originates in the belief that reason should be set free from the imposition of burdensome “riming lawes” (Scourge, E1r). But why did these poets consider the couplet particularly conducive to such boundless discourse? After all, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century theorists described all forms of rhyme—not just stanzas—as restrictive “bands” or “fetters.”34 Moreover, we tend to associate couplets not with boundless speech but with tiresome repetition and uniformity.35 But many early modern writers thought that couplets actually fostered variety and mobility. Sir John Beaumont praised couplets because

Their forme surpassing farre the fetter’d staues,

Vaine care, and needlesse repetition saues.36

Ben Jonson agreed with Beaumont’s assessment of the couplet as a liberating form: he told Drummond that he preferred couplets and considered “crossrhymes and stanzas” to be “forced” because “the purpose would lead him beyond eight lines to conclude.”37 Even Puttenham confirms that the distich, though “not to be accompted a staff, serues for a continuance” (Arte, K2r).38

Looking back on the Elizabethan period through the lens of Milton’s reaction against the couplets of Civil War and Restoration poetry, it is difficult to connect couplets with free verse and thought. But for Marston and the young poets of the 1590s, stanzas were the “troublesome and modern” verse form while couplets restored “ancient liberty” (CPMP, 210). This rapid inversion of the reputation of the couplet between the end of Elizabeth’s reign and the Restoration reveals the importance of keeping a close eye on the shifting implications of poetic forms. If we assume that verse forms had the same implications in 1590 as they did in 1690 or 1790, we are liable to misread the prosodic signals issued by early modern poets and misunderstand controversies like the late Elizabethan war over fashionable artifice and English liberty.

Far-Fetched Livery, Homespun Thread, and Full Nakedness: Rhyme, Clothing, and the Pursuit of Nature

In his work on Spenser’s style and early modern ornamentalism, David Scott Wilson-Okamura draws attention to the fact that premodern poetic theorists (he cites authors from Dante to Samuel Johnson) saw language as the garment of thought, an idea that he notes often seems alien and distasteful to post-Cartesian critics. Wilson-Okamura argues that this disconnect is part of why “ornamentalism still makes us uncomfortable”; there is a “suspicion that ornament is something external, detachable, or superficial—like a façade on a building or frosting on a cake.”39 Wilson-Okamura’s analysis of the deeper philosophical division that informs critical discomfort with the clothing metaphor illuminates not only Spenser’s stylistic choices but the broader understanding of form and its aims in the period. I would like to build on Wilson-Okamura’s insight about the garment of style by thinking through how much room there was for play and disagreement within the metaphor. For, as the satirists of the 1590s make very clear, there are many different kinds of garments available to the gallant and the poet—and some garments are in fact gaudy and superficial. Indeed, attitudes toward dress are frequently a litmus test for poets’ opinions on the proper balance between nature and artifice. The poets whom I have described as licentious rhymers all make it clear that their prosodic and philosophical aim is to discard unnecessary frippery in order to return to homespun clothing or, more radically, to the nakedness of Adam and Eve.

All the satirists look back nostalgically on an idealized English past that was free from the fetters of fashion and opinion, but Joseph Hall spends the most time fleshing out the idea of ancient liberty. The fifth book of his satires is dedicated entirely to abuses of land and property that have crept in since the days of “our Grandsires . . . in ages past.”40 And in his first “moral” satire of the third book, Hall offers a vivid, if somewhat conventional, account of the golden age when men lived on acorns and berries and “naked went: or clad in ruder hide: / Or home-spun Russet, void of forraine pride.”41 This recollection of the simplicity of homespun ancient dress causes Hall to rail against the imported fopperies of courtiers:

But thou canst maske in garish gauderie,

To suit a fooles far-fetched liuery.

A French head ioyn’d to necke Italian:

Thy thighs from Germanie, and brest fro Spaine:

An Englishman in none, a foole in all:

Many in one, and one in seuerall.42

Like Jonson’s character Amorphus the traveler in Cynthia’s Revels (which was acted in 1600), Hall’s courtier is “so made out of the mixture and shreds of forms that himself is truly deformed”; his pursuit of the newest and most “far-fetched” fashions from France, Italy, Germany, and Spain make him a monster who is alienated from his native Englishness.43 Hall’s admiration for the simple sartorial choices of the golden world contrasts starkly with Puttenham’s distaste for the time before the arrival of civilizing poets, when “the people” were “vagarant and dipersed like the wild beasts, lawlesse and naked, or verie ill clad” (Arte, C2r–v).

Elizabethan poets on both sides of the stanza-couplet debate saw courtly dress as an emblem for elaborate continental poetic forms like the stanza. Puttenham uses comparison to the “courtly habiliments” of “Madames of honour” in order to bolster his argument for elaborate poetry in the opening portion of his section on “ornament poeticall” (Arte, Q3v–Q4r). But Joseph Hall draws on the same sartorial analogy to depreciate both stanzaic and quantitative poetry. In the opening lines of the book of “Poeticall” satires, he uses the image of dressed-up stanzas to distinguish his own work from Spenser’s romance:

Nor Ladies wanton loue nor wandring knight,

Legend I out in rymes all richly dight.44

Hall chooses his language carefully here. Spenser frequently uses the word “dight,” which could mean ordered, arranged, clothed, or adorned, but he uses the phrase “richly dight” in particular to describe Duessa: “Most false Duessa, royall richly dight, / That easie was t’inueigle weaker sight” (FQ, 1.12.32). In adopting the phrase, Hall accuses Spenser of crafting stanzas in which adornment covers nether parts as “wanton” as those of his most appealingly false character. In the sixth satire of his first book, Hall condemns English efforts to write quantitative verse as equally contrived: those who “scorn the home-spun threed of rimes” and pursue the “loftie feet” and “numbred verse that Virgil sung” are working against the natural rhythms and native attire of English verse.45 Hall presents couplets as a middle way between two forms of pretension. He agrees with Samuel Daniel that rhyme is the “kinde and naturall attire” of English poetry and that the “single numbers” of quantitative meter will never “doe in our Climate.”46 Though Spenser uses the homespun thread of rhyme, he weaves it into overdressed stanzaic patterns that Hall considers equally contrived.

Marston echoes Hall’s language and makes the denunciation of ornately dressed stanzas more explicit in his first book of satires. His first attempts at satiric poetry were printed in a 1598 volume that also included his Ovidian poem “The Metamorphosis of Pygmalion’s Image,” which was composed in a common stanzaic form rhyming ABABCC. In a transitional poem between the two works, Marston claims that his Ovidian poem was a parody and mocks his own “stanzaes,” comparing them to “odd bands / Of voluntaries, and mercenarians”; like “Soldados” of the current “age” the stanzas

March rich bedight in warlike equipage:

Glittering in dawbed lac’d accoustrements,

And pleasing sutes of loues habiliments.

Yet puffie as Dutch hose they are within,

Faint, and white liuer’d, as our gallants bin.47

Marston describes the ornament of his stanzas in nearly the same words Hall uses for Spenser’s stanzaic rhymes: they are “rich bedight.” Marston, characteristically, cannot leave it at that but expands the image of sartorial richness. Like many of the characters of Marston’s satires, his soldier-stanzas are covered in layer upon layer of deceptive artifice. The stanzas initially appear to be images of martial discipline and order—they may be richly dressed, but they are warlike and marching in order. But in the next two lines, it becomes clear that their suits not only are glittering and lacy but are the “habiliments” of love rather than war. Not only are the soldier-stanzas dressed as lovers rather than warriors, but even this costume is only a cover for the empty puffery of their insides. As he gradually demotes stanzas from soldiers to lily-livered gallants, Marston exposes the pretensions of courtly versifiers who claim that their finely wrought stanzaic forms are emblems of the restrained order and beauty of civilized life. Instead, Marston charges, stanzas are nothing but form—stanzaic poets spend so much time interweaving their rhymes and decking out their lines that they forget to attend to the matter of their poetry. By turning against his own stanzas, Marston attempts to position himself as a defender of inner truth against the encroachments of excessively elaborate rhyme.

Hall and Marston are explicit about the connections between their prosodic choices and their dedication to natural liberty, while the two better-known members of the couplet school, Marlowe and Donne, less frequently speak of stanzas and couplets. But these poets do think about clothing, fashion, and nakedness in their couplet verse in ways that connect them with the other members of the school. In fact, attending to the question of ornament and natural dress in Donne and Marlowe brings out new continuities within and between their work. In his first satire, which Marotti argues “especially reflect[s] the Inns-of-Court setting” in which it was composed, Donne’s satirist contends with a “motley humorist” who sizes up the wealth of all he meets on the street by searching their clothing for “silke” and “gould” and “to that rate / So high or low do[es] vaile [his] formall hatt.”48 Donne accuses his companion of enjoying the “nakedness and bareness” of his “plump muddy whore, or prostitute boy” but then castigates the humorist for despising another kind of nakedness:

Why shouldst thou . . .

Hate vertu though she be naked and bare?

At birthe, and death our bodyes naked are:

And till our Soules be vnapparelled

Of bodyes, they from blis are banished.

Mans first blest State was naked, when by Sin

He lost that, yet he was clothd but in beasts skin.

And in this coarse attire which I now weare

With God and with the Muses I confer.49

This is the serious version of the more sophistic argument in “To his mistress going to bed”:

Full nakednes, all ioyes are due to thee;

As Soules vnbodied, bodyes vncloth’d must bee,

To tast whole ioyes.50

This argument that stripping away gets us closer to the “naked” essence of bodies and souls runs through Donne’s early work. To some extent naked truth and naked virtue are unattainable—the fall has alienated humanity from that blessed state in the time between birth and death—but Donne contends that in the meantime, while conferring with God and the muses, one should at least stick with the “course attire” given by God to cover Adam and Eve after the fall. Like Hall, Donne’s satirist depicts plain, ancient attire as an antidote to the ever-changing “fashiond hats,” “ruffs,” and “Suites” worn by “supple-witted antick Youths.”51 By discarding the newfangled trappings of those who follow fashion and custom, Donne’s satirist hopes to draw nearer to the naked, natural truth.

In Hero and Leander, Marlowe displays a similar concern with stripping away clothing to get to the nakedness beneath, though he approaches the equation of nakedness and truth with more irony than Donne. We can hardly take Leander at his word, for example, when he claims in his sophistic speech to Hero, “My words shall be as spotlesse as my youth, / Full of simplicitie and naked truth.”52 But, for all of Marlowe’s irony, Leander’s association of youth and naked truth does capture something about the poem’s push to uncover the rudiments of desire.53 In Hero and Leander, Marlowe strips down Eros to its bare, youthful, reckless, love-at-first-sight essence. When she makes her entry into the poem, Hero—with her ridiculously ornate sacerdotal robes featuring “Venus in her naked glory” and the blood of slain lovers, her veil of artificial flowers, and a pair of boots with chirruping birds that her handmaid must periodically refill as she walks—is too artificial by half, while “Amorous Leander, beautifull and yoong” is adored by the narrator for the natural beauty of his body.54 As the story of wooing and winning unfolds, Hero is literally and figuratively defrocked. After Leander points out the incongruity of being a celibate “Nun” to Venus and woos her to exchange her vow of chastity for “Venus sweet rites,” Hero trades her ceremonial vestments for a “lawne” through which her “limmes” “sparkl[e].”55 And the penultimate image of the (perhaps) unfinished poem, bookending the opening description of her contrived costume, is the revelation of Hero’s body after she tries to sneak away from the bed but is caught by Leander:

Thus neere the bed she blushing stood upright,

And from her countenance behold ye might

A kind of twilight breake, which through the heare,

As from an orient cloud, glymse here and there.

And round about the chamber this false morne,

Brought foourth the day before the day was borne.

So Heroes ruddie cheeke, Hero betrayd,

And her all naked to his sight diplayd.

Whence his admiring eyes more pleasure tooke,

Than Dis, on heapes of gold fixing his looke.56

The unveiling—or “betray[al]”—of Hero in all her unadorned splendor does seem to be a moment of aesthetic transcendence in the poem. Marlowe quickly undercuts that transcendence with Leander’s miserly gaze and with the concluding image of night “o’recome with anguish, shame, and rage, / Dang[ing] downe to hell her loathsome carriage.”57 I am persuaded by Gordon Braden’s argument that the false morning produced by Hero’s blush invites us to think for a moment that “we are almost on the verge of a giddy affirmation such as John Donne makes in his own contrarian aubade in scorning everything the daytime represents. . . . But we aren’t; this poem is not that one. The real dawn comes on cue, and it is imperious and loud and sweeps everything before it.”58 The fact that Marlowe shatters the vision while Donne bears it out is significant. Yet it is also significant that these two poets are united in imagining the elemental force of Eros warring against and outbraving—even just for a moment—the orderly force of the sun. The vision is more brittle in Marlowe, but it is powerful nonetheless. Indeed, it is telling that Marlowe’s Saturnian digression—in which he aligns lovers and scholars with Saturn and Ops and against Jove and the Fates—has no counterpart in Musaeus’s Greek.59 The poem as a whole seems designed to uncover and revel in the pre-Olympian natural passions that spring up spontaneously in Hero and Leander and to cut through their customary pretensions and posturing. The erotic desire that Marlowe reveals within his youthful characters is not sweet—in fact, it is “deaffe and cruell”—and is fated to end in destruction, but it is undeniably a mighty and elemental force akin to the forces Marlowe unleashes in his plays.60

Gordon Braden has noted that the passage in which Hero’s blush produces a false morn echoes a passage from Marlowe’s youthful translation of Ovid in which Corinna’s “Starke naked” “selfe” is also “Betray’d” to the eye of the speaker.61 Indeed, Hero and Leander, which was likely one of the last things Marlowe wrote before his untimely death in May 1593, is in many ways a revisiting of his Ovid translation, which he likely composed during his time at Cambridge between 1580 and 1587.62 As Heather James has suggested, Marlowe was attracted to Ovidianism (as were many of his contemporaries) because “the audacity and licentiousness of Ovidian elegy represent a deliberately risky and playful kind of speech, developed for Roman imperial subjects to express their residual dissent from the heroic and patriotic line of thinking that had, in Ovid’s day, become an inescapable institution rather than a novel proposition.”63 James contends that Ovid’s political disruptiveness is built into the Latin elegiac distich, which yokes together a dactylic hexameter and a pentameter line.64 But, in Englishing Ovid, Marlowe leaves behind the disruptive unevenness of his lines and pursues other kinds of prosodic looseness. In both All Ovids Elegies and Hero and Leander, Marlowe (who was born and raised in Canterbury) rendered the naturalism of Ovid in the pentameter couplets of Chaucer. In All Ovids Elegies, Marlowe describes his Ovidian verse as “looser lines,” significantly transforming Ovid’s “teneris . . . modis,” tender or soft measures.65 Marlowe’s “looser” implies all the prosodic and moral licentiousness Puttenham attributed to reckless rhymers, and his substitution of “lines” for Ovid’s “modis” also suggests that Marlowe’s verse may be less measured even than his model. The looseness of Marlowe’s couplets in both translations is different from the enjambed looseness of Donne and Marston. He tends to close his couplets and to emphasize his rhymes (in Hero and Leander this is often to humorous effect; indeed, the rhymes in Marlowe’s epyllion often seem to undercut the sententious wisdom offered by the narrator).66 But Marlowe’s couplet poems also contain the seeds of the licentious rhyming of the 1590s: in spite of their end-stops, Marlowe’s couplets allow for a looser and more continuous narrative than sonnets or stanzas. (Comparing Hero and Leander to Shakespeare’s stanzaic Venus and Adonis makes the significance of the couplet very apparent; Shakespeare’s poem does not hurtle onward like Hero and Leander but lingers over and elaborates metaphorically on the lovers and their exchanges in a manner that recalls Spenser more than Marlowe.)67 And, particularly in his Ovidian elegies, Marlowe plays with loose rhythm and varied placement of the caesura to cultivate a witty, conversational voice that resounds in Donne’s later Ovidian experiments.68 But, above all, Marlowe’s couplet verse anticipates the work of the couplet school in its association of the couplet with a licentiousness that strips away custom and artifice in order to gain access to the naked nature beneath.

John Donne, Couplet Poet

The discovery and restoration of natural liberty is the central preoccupation of Donne’s early corpus, unifying an otherwise discordant body of poetry.69 In his verse letters, Donne defines poetry as free discourse among friends and makes the case that rational speech cannot always be pressed into measured verse. In his elegies, he adopts the persona of the libertine as a skeptical position from which he can interrogate the boundaries of desire and distinguish its natural limitations from the arbitrary restraints of poetic and social custom.70 And in his satires, he applies the same test to social and religious practices, discovering few that meet his standards of natural liberty. Indeed, Donne is more extreme than the other couplet poets in his resistance to all forms of restraint. Hall and Marston use the loose couplet to counteract what they see as the social and stylistic excesses of an earlier generation, but they are unwilling to extend their critique of control to marital, political, or religious customs. The young Donne is willing to take on these forbidden subjects and to inspect the grounds of every manner of obligation. He maintains that a certain amount of natural limitation is built into every realm of human life but that the restrictions of nature are less onerous than the dictates of custom. As he argues in Pseudo-Martyr, there are “obligations” that are “natural, and borne in us” and consequently consistent with “rectified reason.”71 These natural obligations are the only ones that truly bind since “any resolution which is but new borne in us, must bee abandon’d and forsaken, when that obedience which is borne with us, is requir’d at our hands.”72

But Donne also believes that it is extremely difficult to distinguish natural from artificial obligations, and, in contrast to most of his contemporaries, he argues that while deliberating we should refrain from binding ourselves at all. On the rare occasions when Donne gives an account of his own life, he describes himself as a man who, with the notable exception of his clandestine marriage, spent the first forty years of his life avoiding obligations. In the oft-quoted preface to Pseudo-Martyr, he confesses his “Indulgence” to “freedome and libertie” in both academic and religious realms: he “did not betroth or enthral” himself “to any one science, which should possesse or denominate” him, and he “used no inordinate hast, no precipitation in binding [his] conscience to any locall Religion.”73 These confessional passages suggest that Donne was interested in cultivating a particular kind of liberty that I will call discursive liberty. Discursive liberty is the liberty to explore a variety of possibilities and argumentative positions rather than binding oneself to a particular institution or system of thought. Discursive liberty can be distinguished from ethical liberty, which is the focus of Ben Jonson’s work. In his poetry, Jonson suggests that he already knows what constitutes the ethical life and that he simply seeks to carve out a circumscribed realm in which he is free to live this life. Where Jonson uses images of standing and dwelling to describe his ideal liberty, Donne uses images of seeking and wandering. And while both Donne and Jonson considered the couplet an apt form for cultivating rational discourse, each poet crafted a peculiar couplet style to accommodate his particular understanding of liberty.

This chapter focuses on Donne’s Elizabethan couplet verse not only because Donne was at the vanguard of this new poetic movement but because the surviving records of Elizabethan and Jacobean engagement with Donne’s poetry indicate that early readers knew Donne primarily, and perhaps exclusively, as a poet who wrote in couplets. Not a single allusion to the “Songs and Sonnets” has been found prior to 1609, when an anonymous version of “The Expiration” was set to music in Ayres: by Alfonso Ferrabosco.74 There is much more evidence that Donne’s satires, elegies, and epigrams were being circulated, read, and imitated around the turn of the century: it is clear that Hall and Guilpin had access to Donne’s verse in manuscript, and A. J. Smith’s John Donne: The Critical Heritage records seven references to the verse letters, elegies, epigrams, and satires between 1600 and 1612.75

Though these scattered allusions suggest that Donne’s couplet poems were better known than the “Songs and Sonnets,” the brief comments of two poets connected to Inns of Court literary circles—Francis Davison and Ben Jonson—reveal more about the portions of Donne’s early corpus that were favored by early readers. In a manuscript dated circa 1606, Francis Davison, a poet and anthologist who was admitted to Gray’s Inn in 1593, explicitly mentions only couplet verse in his list of “manuscripts to get.”76 He notes that he would like to acquire “Satyres, Elegies, Epigrams, etc. by John Don.”77 Next to this note, Davison jots down two potential sources for Donne’s verse: “some from Eleaz. Hodgson, and Ben Johnson.”78 Davison was right to see Jonson as a likely source for Donne manuscripts. Jonson’s epigram “To Lucy, Countess of Bedford, with Master Donne’s Satires” indicates that he sent a copy of Donne’s satires to their shared patroness.79 He also testified to William Drummond that he was particularly impressed with Donne’s youthful verse, affirming “Donne to have written all his best pieces ere he was twenty-five years old,” that is, before 1597.80 Since Jonson opens the conversations with Drummond with the revelation that he had written a treatise proving “couplets to be the bravest sort of verses,” it is likely that Jonson’s appreciation of Donne’s youthful verse is due, at least in part, to Donne’s role as a couplet pioneer.81

In fact, these allusions may suggest that Donne wrote exclusively in couplets during his early career at the Inns of Court. Since no sixteenth-century manuscripts of Donne’s poetry survive, we can only speculate about why the couplet poems circulated more widely than the “Songs and Sonnets.” However, Helen Gardner and Arthur Marotti argue that the lack of early references to the “Songs and Sonnets” is due to a deliberate effort on the part of the poet to restrict their circulation.82 Gardner posits that Donne guarded the “Songs and Sonnets” more jealously than the couplet poems because he composed them after 1597, when his appointment as Sir Thomas Egerton’s secretary might have made him reluctant to circulate libertine lyrics.83 If Gardner’s hypothesis is correct, then Donne dedicated himself entirely to couplet verse during his years at the Inns of Court. This apprenticeship to the couplet would explain much about Donne’s innovative approach to stanzaic poetry. Donne learned the poetic trade by working in the medium of the loose Chaucerian couplet. When he began to write the “Songs and Sonnets,” he loosened up the “fetter’d staves” by applying tools he had developed for the elegies and satires: he continued to bend poetic form to accommodate dramatic speech and discursive thought by inventing his own stanzaic patterns for each poem and by using enjambment and rough rhythm.84

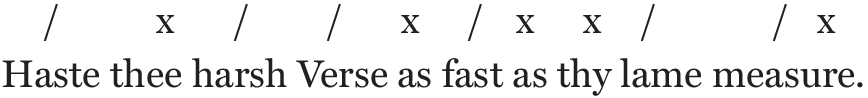

Donne’s verse letters from his earliest years at the Inns of Court provide a window into his early conception of his poetic project and suggest that his harsh and conversational style grew out of his attempts to cast off the strictures of measure and redefine poetry as free discourse among friends. In one of his earliest verse letters, “To Mr. T.W.,” Donne provides a clear, if unsystematic, account of his poetic priorities. He presents the poem as an apology for his poetic shortcomings, but it is also an apologia for a new poetic mode:

Haste thee harsh Verse, as fast as thy lame measure

Will give thee leaue, to him my payne and pleasure.

I have given thee, and yet thou art too weake,

Feete, and a reasoning Soule and tong to speake.

Plead for me, and so by thyne and my labor,

I am thy Creator, thou my Sauior.85

The fourteen-line poem could almost be described as an antisonnet: instead of displaying his mastery of poetic artifice with an intricate rhyme scheme, Donne offers a loose gathering of seven enjambed couplets.86 And instead of cultivating the “sweet” and “sugared” style generally associated with the sonnet, Donne declares in the third word of the poem that his verse is “harsh.”87 The claim to harsh and lame verse is not simply self-deprecating rhetoric since Donne then proceeds to break the most basic rules of Elizabethan prosody as laid out by Puttenham and Gascoigne. Over half of the rhymes in the poem are feminine, and Donne immediately departs from the regular iambic line. In the first line, unexpected stresses on “harsh” and “lame” emphasize the phrases “harsh Verse” and “lame measure”:

It is no accident, of course, that the misplaced stresses fall on the key adjectives Donne uses to characterize his halting measure.

Decades later, Ben Jonson would object to such intentional roughness in a passage on style in his commonplace book. After complaining about those who labor only for ostentation, Jonson piles equal opprobrium on those who “in composition are nothing, but what is rough and broken. . . . And if it would come gently, they trouble it of purpose. They would not have it run without rubs, as if that style were more strong and manly, that struck the ear with a kind of unevenness. These men err not by chance, but knowingly, and willingly.”88 Jonson views such deliberate unevenness as a mere eccentricity, equivalent to trying to distinguish oneself sartorially with “some singularity in a ruff, cloak, or hatband.”89 Donne, however, offers a more philosophical justification for his knowing and willing disregard of poetic rules in the sixth line of the verse letter quoted above, where he describes himself as a poetic “Creator” who has given his verse “Feete, and a reasoning Soule and tong to speake” (Verse Letters, 6, 4). Playing with scholastic definitions of man, Donne defines his verse as a rational creature that is capable of speech. This definition of poetry echoes throughout Donne’s verse letters, where he repeatedly suggests that the purpose of poetic exchange is to allow “friends absent” to “speake” and thereby “mingle” their “reasoning Soule[s].”90 But what is striking about this particular verse letter is not simply that Donne emphasizes rational speech, but that he decouples reason from measure. Donne’s poetic elders insisted on the preeminence of number and measure in poetic creation, touting it as a sign of rationality and even divinity since, as Puttenham notes, “God made the world by number, measure and weight” (Arte, K1r). But Donne turns the creator-creature analogy against advocates of measure: since the essence of the creature lies in its “reasoning Soule,” it would be foolish to obsess over the condition of its “Feete” (Verse Letters, 4). Just as a rational soul can be joined to lame feet, rational verse can be joined to halting measure.

In the verse letters, Donne attempts to make poetry a forum for intimate and rational speech by loosening the restrictions of measure, but his love elegies offer a more sustained attack on artificial limitations. At times, the erotic radicalism of the elegies seems to spring from sheer youthful delight in impertinent wit. But, when the elegies are read alongside Donne’s early satires and verse letters, it becomes apparent that they engage thoughtfully with questions of romantic freedom and thralldom. Like the satires of Hall and Marston, Donne’s elegies suggest that the fashions of courtly love poetry have actually spoiled love affairs for both sexes by making men into servile but swaggering gallants.91 Although the elegies do not constitute a unified book because Donne uses a variety of male personae, some whining and some truculent, they are unified by their attempts to free English poetry from “servile imitation” of Petrarchan tropes and English youths from debasing slavery to their mistresses.92

One of Donne’s primary methods for liberating young men from the spell of Petrarchism is to use shock and disgust to shatter ideals about the youth and beauty of the mistress, as he does in “The Anagram,” “The Comparison,” and “Autumnal,” or about her virtue and chastity, as he does in “Nature’s Lay Idiot,” “Change,” and “Oh Let me not serve so.” In one of his most obscene and misogynistic elegies, “Love’s Progress,” which waggishly proposes that a woman’s “Centrique part” is “the right true end of loue,” Donne defends his erotic iconoclasm by arguing that art deforms love:

And Loue is a Bear-whelp borne; if we ouer-lick

Our Loue, and force it newe strange shapes to take

Wee erre, and of a lumpe a Monster make. (Elegies, 36, 2, 3–5)

The lines refer to an ancient myth that bear whelps were born as lumps of matter without form and subsequently licked into an ursine shape by their mothers.93 The most well-known use of the bear-whelp story is in the final book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where Pythagoras uses it as an instance of the mutability of the natural world:

The Bearwhelp also which

The Beare hath newly littred, is no whelp immediatly.

But like an euill fauored lump of flesh alyue dooth lye.

The dam by licking shapeth out his members orderly

Of such a syse, as such a peece is able too conceyue.94

Donne’s allusion imports some of the larger cosmological implications of the Ovidian original: he uses the bear-whelp image to suggest that variable and wild forces are a permanent feature of the natural world.95 Ovid uses the image to indicate that art can restrain these forces and produce order out of the “euill fauored lump” of nature. But Donne adds a new twist to the metaphor by arguing that there is a danger of applying too much art and forcing Eros into “strange shapes” (Elegies, 4). This is what Petrarchan poets have done for centuries, producing forced and “strange” conceptions of love in poems that take the “strange shapes” of Italianate sonnets.

In the elegy titled “Change,” Donne once more explores humanity’s natural wildness and wonders whether even the expectation of constancy and monogamy is a “strange shape” that custom has forced on love. The poem exemplifies Donne’s understanding of verse as rational speech since it opens with a decidedly argumentative word—“Although”—and immediately launches into what sounds, for a moment, like a theological disputation among friends:

Although thy hand, and fayth and good works too

Haue seald thy love which nothing should vndoo,

Yea though thou fall back, that Apostasee

Confirme thy love; yet much much I feare thee. (Elegies, 1–4)

Donne uses the same licentious play with the language of theology that we saw in “Hast[e] thee harsh verse,” but here Donne’s sexual puns raise serious questions about the guarantees of romantic fidelity. Since the twelfth century, Christian marriage had required two “seals”: a present tense vow—the giving of “hand and fayth”—and consummation—the “good works” Donne attributes to his lady.96 In the first three lines, Donne seems to hold up the primitive seal of erotic deeds as a more reliable confirmation of love than the bands of marriage. But in the fourth line, the witty play and its celebration of desire come to an abrupt halt at the caesura as the speaker admits his crippling fear. The passion and pathos of the confession make it difficult to discern which of the six monosyllables after the caesura should be accented:

After commending the lady for her physical good works in the first three lines, the speaker suddenly reveals that he mistrusts even this corporeal seal of love. Neither the more primitive seal of consummation nor the communal seal of marriage is sufficient to secure the love of his mistress or guard him from fears and doubts.

In a series of conditionals and comparisons that show his wavering mind at work, the speaker then goes on to explain that the source of his fear is nature itself, which he maintains is governed by change. In order to demonstrate that natural love has no permanent or particular object—that “Women are made for men, not him nor mee”—he turns to the animal world:

Foxes and Gotes, All beasts change when they please,

Shall women, more hott, wyly, wild then these

Be bound to one man, and did Nature then

Id’ly make them apter to’endure then men? (Elegies, 10, 11–14)

The lines play on the ancient belief that women are changeable and men constant, but here feminine mutability is naturalized through the comparison with beasts. The speaker presents himself with a choice between two equally unappealing forms of degradation: female erotic liberty may be “natural,” but it is associated with base and lecherous beasts like foxes and goats, while masculine constancy is associated with artificial instruments of slavery—clogs and chains. Though the speaker expresses his distaste for the “hott, wyly, wild” liberty of women, he argues that men must follow suit or endure the one-sided enslavement characteristic of the asymmetrical courtly love tradition.

After expanding on the charge that women are licentious by comparing them to “plough-land” and the “sea,” the speaker reaches an impasse in a passionate outburst:

By Nature which gaue it, this libertee

Thou lov’st, but Oh, canst thou love it and mee? (Elegies, 17, 17, 20–22)

The lines sit near the center of the elegy and encapsulate the conflict between two irreconcilable desires that Donne attempts to negotiate in this poem: the desire for liberty and the desire to love and be loved by a particular individual. The desires are gendered here, but in other poems Donne reverses the roles, associating men with liberty and women with fidelity.97 This suggests that Donne sees the tension as a fundamental feature of human love rather than a result of female vice. The tension is familiar from more idealistic love poetry like Spenser’s Amoretti, where the speaker must address his own resistance to the golden “fetters” of matrimony and his lady’s reluctance to “loose [her] liberty” (SP, 37.14, 65.2). But Donne rejects the Spenserian solution in which both lovers embrace the “Sweet . . . bands” of mutual servitude (SP, 65.5). He maintains that the natural love of freedom must be accommodated since no manner of artifice can overcome it.

In the remainder of the poem, the speaker attempts to find a middle ground between the desire for freedom and the desire for constancy. After reiterating the point that loving one woman would be “Captiuity” and loving all would be “a wild roguery,” the speaker uses a final natural metaphor to present his middle way:

Waters stinck soon yf in one place they bide

And in the vast Sea are worse putrifide:

But when they kisse one banke and leauing this

Neuer look backe but the next banke do kis

Then are they purest. Change is the Nurcery

Of Musick, Ioye, Life, and Eternity. (Elegies, 29, 30, 31–36)

This conclusion, particularly the claim that change is the nursery of eternity, has sometimes been dismissed as “characteristic sophistry” since it is directly opposed to the more orthodox Spenserian view that “Eternity . . . is contrayr to Mutabilitie” (FQ, 7.8.2.).98 But William Rockett has made the case that the poem is a genuine “argument for liberty and pleasure” that rests on the “pseudo-Epicurean idea” that flux and change are generative.99 The poem is certainly not a serious philosophical case for change; at most it is an exploration of what it would mean to reconcile liberty and constancy in love. But the conclusion, with its emphasis on purification through movement, is consistent with a dedication to accommodating roughness and energy that runs throughout Donne’s early verse. Since a restless desire for change and a love of freedom seem to be natural to us, he argues, we should embrace these qualities and use them to purify ourselves from putrid obligations and ideas. In a world where love is a bear whelp and women are foxes, it is best to preserve a free mind and heart rather than hastily binding oneself to imperfect creatures.

Donne offers a more sustained and plausible argument for the productivity of mobility and struggle in “Satyre 3,” which is titled “Of Religion” in some manuscripts. In the poem, which critics have dated to 1593–98 primarily on the basis of Donne’s religious biography, Donne inverts the theological double entendres of the elegies. Instead of connecting his love affairs to religious debates, he explores the “Soules deuotion” to “our Mistres fayre Religion.”100 It is no coincidence that Donne uses the metaphor of a mistress in the opening lines of the poem and in the famous section in which he compares religious inclinations to “Lecherous humors” (Satyre, 53). “Satyre 3” addresses the same question about fidelity and freedom that concerned Donne in the love elegies: given the natural desire for freedom and the unreliability of earthly objects of devotion, how can we permanently bind ourselves to a particular mistress—whether that mistress is a woman or a church? With his well-known image of the “high hill” of truth, he argues that the pursuit of knowledge requires freedom from arbitrary human laws and tolerance for imperfections and roughness (Satyre, 79). In the satire, Donne uses his rough style more precisely and effectively than in any of the couplet poems. By presenting his argument for religious liberty in the loosest verse of his career, Donne makes the case that it is the task of poetry to reproduce rather than restrain the disorderly effort involved in the “minds endeauors” (Satyre, 87).

Despite its religious subject, “Satyre 3” is in line with the courtly satires of the 1590s in its condemnation of custom and fashion. The poem endeavors to expose what Donne would later call “fashionall, and Circumstantiall christians, that doe sometimes some offices of religion, out of custome, or company, or neighborhood, or necessity.”101 In the satire, Donne argues that such Christians are bound to particular churches because they are too literal minded in their response to the passionate question posed by the satirist: “Seeke true Religion; Oh where?” (Satyre, 43). The first three satiric characters attempt to locate religion in particular, earthly places: Mirreus thinks religion has been “vnhous’d” from England and therefore looks for her “at Rome” (Satyre, 44, 45). The reformed Crants also attempts to circumscribe religion to a particular place, tying himself to her “only” who is called religion “at Geneua” (Satyre, 50). Donne declares his resistance to such circumscription of religion to a particular location in a letter to his close friend Sir Henry Goodyer: “You know I never fettered nor imprisoned the word Religion; not straightning it Frierly, ad Religiones factitias, (as the Romans call well their orders of Religion) nor immuring it in a Rome, or a Wittemberg, or a Geneva.”102 Playing on the etymological connection between the word “religion” and the Latin for fettering, ligare, Donne depicts religious orders and churches as factitious, man-made prisons. The adherents of these religions have immured themselves within comfortable, safe, and definite theological systems and opted out of the search for “true Religion” (Satyre, 43).

Mirreus and Crants may restrict religion to Rome and Geneva, but they are at least described as leaving home and “Seek[ing]” religion (Satyre, 45). Graius, the representative of the Church of England, is the most captive to place since he “stayes still at home here” and thinks that “Shee / Which dwells with vs is only perfect” (Satyre, 55, 57–58). Donne may be particularly hard on the Church of England because it was the most comfortable and obvious choice for the young English lawyers he addresses in the satires, but he objects in particular to the fact that the English derive their religious obligations from “lawes / Still new, like fashions” (Satyre, 56–57). Graius’s godfathers are hypocritical as well as misguided since they try to pass off rules that are as new as the latest sartorial fashion as if they were eternal and permanently binding laws. In the remainder of the satire, Donne attempts to check the errors of “fashionall . . . christians” by depicting the pursuit of true and natural religious obligations as a rugged and laborious enterprise.103

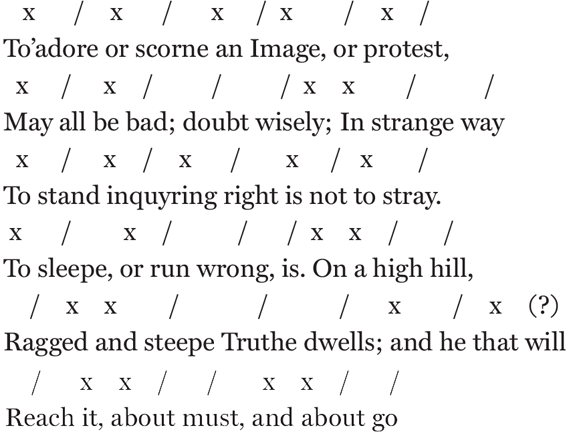

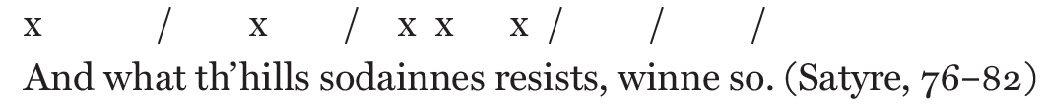

The end of “Satyre 3” is unique among the Elizabethan satires since it does not simply censure contemporary society, but offers a positive statement of Donne’s own religious ideals. For the circumscribed places admired by the devotees of false religion, Donne substitutes a metaphorical place, the “high hill” where “Truthe dwells” (Satyre 79, 80). A hilltop is a naturally rather than an artificially circumscribed place, protected by the steepness of the ascent rather than factitious walls. In order to ascend the huge hill, Donne argues, the religious seeker must be willing to accommodate the irregularities of the path. The lines that describe this painful inquisition are among the roughest in Donne’s licentious early corpus. Indeed, the rough rhythm of this passage can be interpreted in any number of ways. Here is one effort to capture its idiosyncrasies:

Every detail of these couplets is calculated to reinforce the argument that the steep hill of knowledge can be surmounted only by ponderous and disorderly effort.105 Long, inverted sentences wind about the verse paragraph, overflowing line endings and couplet units. Frequent caesuras and an extremely irregular rhythm produce a halting pace. And Donne punctuates this paragraph of couplets with heavily accented, monosyllabic verbs—aske, seeke, doubt, stand, goe, winne, strive—that issue a call to intellectual action culminating in a final, emphatic command: “To will, implyes delay, therfore now do” (Satyre, 85).

Donne plays with this relationship between will and deed in a remarkable enjambment between lines 80 and 81 (“will / Reach”). Here, he not only separates the auxiliary verb from the main verb but, in doing so, violates one of our most fixed expectations about the pentameter line: that it will conclude with a heavily accented word. Donne carefully chooses an auxiliary verb—“will”—that can be accented or unaccented and then follows it with a trochaic foot on the next line. While the metrical contract makes it seem natural to stress “will” at the end of the line, stumbling over “Reach” at the beginning of the next line prompts a debate: should “will” be left unaccented because it is the auxiliary verb next to an accented main verb, or should it be accented because it is in a strong position at the end of the line?106 Donne’s careful manipulation of accentual expectations across the line ending reinforces the idea that the rules of the pursuit are far from settled and that the “will” to knowledge is insufficient without the messy struggle to “Reach” the top of the rugged hill. Donne’s loose use of measure and number is an essential component of the attack on human measures that was also at the heart of the verse letters and elegies. At their best, the “minds endeauours” are far from ordered and neat, and to circumscribe their discursive movements would be to cut off the search for truth (Satyre, 87).

Donne’s efforts to represent the discursive struggle in poetic form are even more striking if we read this passage alongside a comparable one from a poet who dedicated himself to interwoven, stanzaic verse. The passage from book 1 of Spenser’s Faerie Queene describes a portion of Redcrosse Knight’s journey to redemption within the House of Holiness. Spenser, like Donne, expands on the adage from the Sermon on the Mount that the way that leads to life is narrow (Matthew 7:14):

The godly Matrone by the hand him beares

Forth from her presence, by a narrow way,

Scattred with bushy thornes, and ragged breares,

Which still before him she remou’d away,

That nothing might his ready passage stay:

And euer when his feet encombred were,

Or gan to shrinke, or from the right to stray,

She held him fast, and firmely did vpbeare,

As carefull Nourse her child from falling oft does reare. (FQ, 1.10.35)

While the religious struggle described in Donne’s poem is a solitary one, Spenser’s hero is accompanied and all but carried up the path by the “godly Matrone” Mercy. Though the “narrow way” to heavenly contemplation may be strewn with rocks and surrounded with thorns, Spenser’s prosody controls rather than imitates the roughness of the ascent. Like Redcrosse Knight’s divine guide, Spenser’s regular iambs, end-stopped lines, and interwoven rhymes firmly bear up the stanza. Spenser does not shrink from difficulty or disorder in his romance, but his dedication to measure produces a constant undercurrent of order in the most chaotic scenes of the poem. The prosodic differences between these two passages about religious struggle reveal much more than a difference of style or temperament. They reveal that Spenser and Donne fundamentally disagree about the purpose of poetic form and the way that it should interact with the matter of the poem. For Spenser, at least in his later years, form should contain an unruly language and make poetic art a reflection of divine creation. For Donne, form should reflect not the ideal of heavenly order but the reality of earthly struggle.107 This belief that poetry can serve its proper function only when it is freed from the strict limitations of “riming lawes” was at the heart of Donne’s early verse and of the poetic rebellion he initiated (Scourge, E1r). For the new poets of the 1590s and their Inns of Court audience, the discursive couplet was not simply a badge of a philosophical and social revolution, but a way of embodying critique at the level of form.