1

What Is Magic?

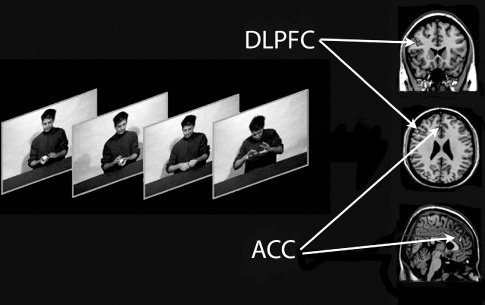

When I was thirteen years old, my school friend Arthur Roscha made an egg appear from behind my ear. Arthur’s egg trick won’t be remembered as one of the world’s best magic tricks, but as a young teenage boy, I was pretty impressed: how could an egg simply appear from behind my ear? By that age, I no longer believed in “real” magic and was pretty confident that Arthur didn’t have any supernatural powers. Although my rational self knew that I had been tricked by some clever illusion, I simply could not explain the thing I had witnessed with my very own eyes. Deep inside my brain—the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to be precise—there was a serious conflict between what I thought was possible and what I had just experienced.

Magic is one of the most captivating and enduring forms of entertainment, with magicians all over the world baffling and amazing audiences by creating magical effects. Magic deals with some of the most fundamental philosophical and psychological questions, and yet, unlike many other forms of entertainment, it has received relatively little attention from people outside its sphere. In recent years, psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers have started to study magic more systematically, and the science of magic is now a field of its own.1 Rather than simply speculating about why magic works, we have scientific data that helps explain the psychological mechanism that underpin these wonderful experiences.2 In this book, we will discuss the latest scientific research on magic, which provides intriguing and often unsettling insights into the mysteries of the human mind. Magic exploits surprising and even counterintuitive psychological principles, and understanding these cognitive processes will challenge your beliefs about your own capabilities. This book will also help you appreciate the complex and almost magical neurological mechanisms that underpin many of our daily activities. Although magic is one of the oldest forms of entertainment, we are only just starting to ask some of the most pivotal questions: What is magic, and why do people endorse magical beliefs? How much of your world do you really perceive? Can you trust what you see and remember? And are you really in charge of your thoughts and actions? We will start by exploring some of these questions before focusing on the psychological principles that magicians exploit. In the final part, we will see how magic is applied to areas outside entertainment and discuss some of the reasons we are so captivated by magic. Before we can answer any of these questions, however, we must take a closer look at the nature of magic.

By now, you may also be wondering how a teenage boy managed to defy the known laws of science and make things appear out of thin air. I’m afraid you may find the answer to this mystery rather disappointing. And once you know how the trick is done, it will never evoke this magical sense of wonder again. Discovering the secret behind magic tricks is often a bit of a letdown. Indeed, a recent study conducted by magician Joshua Jay and a psychology research team led by Dr. Lisa Grimm at the College of New Jersey discovered that most people do not want to find out how a trick is done, which is why I will reveal the secrets only when necessary. In Jay and Grimm’s study, participants were shown video clips of magic tricks that were far more impressive than Arthur’s. In one clip, for example, the magician made a helicopter appear. The participants were then given a choice between discovering how the trick was done or watching another magic trick. Sixty percent preferred watching another magic trick, whereas only 40 percent wanted to know how the trick was done, illustrating that people are more interested in experiencing mysteries than in solving them.3 Interestingly, when my student Rhianne Stewart asked people what they liked and disliked about magic, she discovered that although most people don’t want to discover the secret, some don’t like magic because they don’t know how it is done.

I am one of the 40 percent who really want to know how a trick is done. And so, Arthur’s egg trick started my fascination with magic: how could such a thing happen? At the time, I had no reason to question the authenticity of the egg. Why would it be anything other than real? To the best of my knowledge, all eggs had hard shells, and when you cracked them, they released a messy liquid. There was simply no way that Arthur could have hidden the egg inside his hand or behind my ear without me noticing it. Of course, this reasoning was based on my erroneous assumption that the egg in front of my eyes was real. But although the egg that had just materialized from behind my ear looked like a real egg, it was actually made of soft sponge covered in white fabric. This trick egg could be squashed into a fraction of its size and thus easily hidden inside your hand. I later learned that secretly concealing objects inside your hand is known as palming, one of the most powerful methods in the magician’s toolkit. Arthur simply palmed the tiny squashed-up sponge egg inside his hand, reached behind my ear, and released the pressure from his hand. The tiny piece of sponge then expanded to its full size. All he had left to do was reveal the egg, which I assumed had appeared from behind my ear.

I had just experienced a truly impossible event, and teenage Arthur was very pleased with himself. But although the trick was indeed pretty cool, I was more fascinated by the way in which such a simple gimmick could trick people. It is fair to say that this sponge egg changed my life. From that day on, I was captivated by the art of magic. Arthur and I borrowed every book on magic from our local library and spent pretty much every minute outside school learning new tricks. (To be honest, we also spent a lot of time during school practicing our tricks, which I like to think explains my poor grades.) After reading all the publicly available books on magic, we discovered magic shops and were gradually introduced into the secretive world of magic, which opened doors to new knowledge and tricks. We attended magic conventions, where some of the world’s top magicians would share their thoughts on magic and teach fellow magicians new tricks. Even nowadays, these magic conventions have massive dealer halls where magic traders from around the world sell their newest tricks and gimmicks, and as any magician will tell you, most novice magicians are seduced into spending lots of money on tricks they will never perform. However, one of the main attractions of these magic conventions is simply the chance to hang out with fellow magicians and discuss your thoughts and ideas about magic. You will always find small groups of magicians huddled around a table, each clutching a deck of playing cards, discussing magic into the early hours of the morning.4

Magicians often become obsessed with magic and dedicate their entire lives to this mysterious world of deception and illusion. As teenagers, Arthur and I spent pretty much every spare moment of our lives practicing tricks and talking and thinking about magic. My PhD student Olli Rissanen interviewed many of Finland’s best magicians to see what it takes to become a professional magician.5 It turns out that it takes at least ten thousand hours of practice, which coincides with the amount of time that a musician, athlete, or any other performer needs to become a master of their craft.

Although magic involves countless hours of practicing sleight of hand and choreographing magic routines, it is also an intellectual activity. As such, magicians spend a lot of their time thinking and theorizing. Many of the top magicians, such as Juan Tamariz or Ricky Jay, are not only great performers but also have a thorough intellectual understanding of their art. They are able to dissect and explain individual magic tricks in great detail and have powerful insights into how magic works in general.6 But if you ask such a magician what magic is, most will go blank and struggle to come up with a meaningful definition.7 Defining magic turns out to be much more difficult than one might think. But thanks to the combined work of magicians, historians, philosophers, and psychologists, we are getting a better understanding of what it is and what it might ultimately be capable of. In this first chapter, we will explore some of the psychological mechanisms that underpin our experience of magic and look at why we all experience magic differently.

Is Magic about Tricks and Deception?

I frequently lecture to the public about the psychology of magic. I usually start by performing a few magic tricks, after which I ask members of the audience to come up with their own definition of magic. People’s responses vary, but a common suggestion is that magic is all about tricks and deception. Thinking about magic in these terms seems like a good starting point because it’s virtually impossible to imagine a magic trick that does not involve deception and trickery. Indeed, many magicians see it as their job to simply fool their audiences.8 But is it best to define magic in terms of deception? If we think about magic from a psychological perspective, we need to ask ourselves whether deception elicits the same emotional response that you typically experience when you have been successfully fooled.

Performing magic for magicians is notoriously difficult. This is largely because magicians may already know the trick being performed or are familiar with some of the techniques being used, so they know what they should pay attention to. However, not only can magicians fool fellow magicians, they often pride themselves on doing so. In his book, Designing Miracles, Darwin Ortiz notes that “whenever a magician describes a magic performance that particularly impressed him, he almost always uses the word ‘fooled.’ He’ll say things like: ‘He fooled the hell out of me,’ ‘I’ve never been so fooled in my life.’”9 As a nonmagician, you may not be particularly impressed by such tricks, but magicians love them precisely because they have been fooled. Does this mean we can equate the pleasure we experience when being amazed by a magical illusion to simply being deceived or fooled?

In everyday life, most people are unhappy (or even angry) when they realize that they’ve been fooled. A secondhand car salesman may use lies and deception to convince you that all of his cars are in perfect condition. You might even walk away feeling pleased with yourself for having purchased a bargain. But this feeling of euphoria quickly turns to disappointment once you realize that you have bought a lemon. The emotional reactions elicited by being tricked into buying a bad car and by seeing an actual lemon magically appear under a magician’s cup are very different, which suggests that magic and deception tap into different psychological mechanisms. At the very least, this difference shows that magic is a distinct experience.10

Jamy Ian Swiss, a prominent magic theorist, points out that our enjoyment of magic is strangely paradoxical given the negative emotions we generally experience when we are being fooled.11 Most people who go to see a magic performance know that they are being deceived and lied to, yet they still find this to be a pleasurable experience. At first, this paradox did not make any sense to me, and I spent a lot of time searching for ways to resolve it. However, it turns out that once you look more deeply into our motivation and the function of lying, the paradox resolves itself. It is commonly assumed that all lies are bad and that we don’t like being lied to. But both assumptions turn out to be wrong.

Conducting research on lying is rather challenging, in that it’s very difficult to discover if someone is lying or not. However, there are several researchers who have tried to establish the frequency with which people lie, and the results are rather startling. For example, a study by James Tyler and colleagues asked university students to get acquainted with one another through a ten-minute conversation, during which the researchers counted the number of times that participants lied. Rather surprisingly, within this relatively short time period, participants lied on average 2.18 times.12 Similarly, this study asked students to keep a diary and note when they lied. Almost all of the students admitted that they had lied during the week they kept their diary and, on average, had lied to 34 percent of the people with whom they had interacted. Students are not the only individuals who frequently lie. A survey conducted by the Observer, one of the United Kingdom’s largest newspapers, revealed that 88 percent of respondents admitted to having feigned delight when receiving a bad Christmas present, and 73 percent had told flattering lies about a partner’s sexual ability.13

If everyone around me is lying, why am I not getting frustrated all the time? And if lying is bad, shouldn’t I avoid people who don’t tell me the truth? It turns out that this is why there is no paradox regarding magic and deception. There are lots of situations in which we actually prefer living with a lie rather than the truth. For example, if you are asked whether you like your Christmas present, it is far less awkward to tell a fib than to reveal that you really don’t like the new jumper. This lack of motivation to discover the actual truth is known as the Ostrich Effect, and it may account for why most affairs will remain undiscovered, even though 40–50 percent of men and women engage in extramarital relations.14

Living in a world where everyone always told the truth might actually be rather unpleasant. For example, imagine you have a secret crush on a workmate and would like to ask her out on a date. After weeks of plucking up courage, you walk up to her desk and ask whether she would like to join you for lunch. She is clearly not interested in you, but rather than telling you so directly, she says that she is currently very busy and therefore won’t be available. Hopefully, you will take the hint and in your own way conclude that she is less interested in you than you had hoped. Although she lied, the truth would have been far more hurtful. Our social world is very complex and fragile, and these small lies and evasions of the truth are often used as a social lubricant.

Our paradoxical distaste for deception and enjoyment of magic is now beginning to crumble. The nail in the coffin is the fact that we actually prefer to be surrounded by people who are more economical with the truth. For example, introverts lie less than extraverts, yet we typically perceive them as being socially awkward.15 Indeed, Aldert Vrij has suggested that we find some people to be socially awkward precisely because they don’t lie enough.16

Now that we have taken a closer look at our psychological reactions toward lies and deception, it becomes apparent that our enjoyment of magic and our experience of deception may not be all that paradoxical. In the final chapter, we will see that current psychological theories help explain how the context of a magic performance allows us to embrace even negative emotions and experience them as aesthetically pleasing. However, for the time being, let me simply say that although deception forms an important part of magic, it involves much more than simply tricking people.

Is Magic about Illusion?

When I ask my students to define magic, they often claim that it is all about illusion. Illusions are typically thought of as experiences that do not match with the true state of the world. There is, however, much more to illusions than meets the eye, and we will look more closely at their nature in chapter 5. But for the time being, this definition is sufficient.

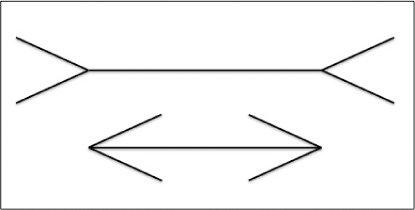

The figure below depicts two horizontal lines. Which of these appears longer?

Figure 1.1 Müller-Lyer Illusion

For most people, the top line looks substantially longer than the bottom one, even though the two lines are physically identical. This is known as the Müller-Lyer Illusion, one of the most studied illusions in vision science. Among its many interesting properties is the fact that the strength of the Müller-Lyer Illusion is not affected by knowing that it is present. These properties are the reason that magicians frequently use such illusions to create their magic effects. However, the experience evoked by magic differs from simply experiencing a sensory illusion.

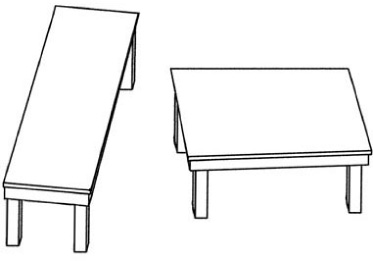

To see this more clearly, consider one of my favorite visual illusions, Roger Shepard’s Turning the Tables.17 Look at figure 1.2 and decide which of the two tables will fit more easily through a narrow doorway. Most people will select the one on the left because it appears much narrower than the one on the right. However, both table surfaces are identical.18 As in the case of the Müller-Lyer Illusion, Turning the Tables is very effective even when you know that it is an illusion. Even though the rational self tells you that the surfaces are identical, you simply cannot perceive them as such. In the real three-dimensional world, the table surfaces would certainly be different, and your visual system is generalizing your knowledge about real-world objects to influence how you perceive two-dimensional shapes.

Figure 1.2 Roger Shepard’s Turning the Tables

We will learn much more about the relevant perceptual processes in subsequent chapters, but for now, what is important is the fact that even when you know such illusions are present, the mismatch with reality is still there. Indeed, me telling you about these illusions turns a simple drawing into something much more intriguing. As philosopher Immanuel Kant already noted, “This mental game with sensory illusion is very pleasant and entertaining.”19 Likewise, most people remain intrigued even once they know how illusions are accomplished. Magician Thomas Fraps suggests that our enjoyment of visual illusions, despite knowing how they are accomplished, differentiates magic from illusions.20 Magic is far more fragile: in contrast to the case of the Müller-Lyer Illusion, once you know that the egg appearing from behind your ear is a gimmick, the enchantment of the magic trick evaporates.

The same point can be made by noting that—as we will learn later on—your perceptual awareness of the world and even of yourself is an illusion. So if everything you experience is effectively an illusion, and if illusion is the basis of magic, then why don’t we continually have magical experiences during our day-to-day lives? Even though illusion can play an important role in magic tricks, magic is about much more than illusion.

Is Magic about Special Effects?

Another possible characterization of magic is in terms of special effects, such as those encountered in cinema. In the early days of cinema, there was a close link between magic and filmmaking; during the Victorian era, magicians such as John Nevil Maskelyne or Howard Thurston regularly incorporated short film screenings into their magic shows.21 Similarly, French illusionist and film director Georges Méliès combined magic and film to create some of the earliest special effects, and many of his achievements paved the way for modern cinema.

More recently, computer-generated special effects have given Marvel’s superheroes their superpowers and have enabled Harry Potter to perform wonders that most magicians can only dream of. Such effects look so realistic that it’s often difficult to distinguish them from reality. But even though I have no idea how these effects are achieved, I do not experience them as magic; at the back of my mind, I’m aware that computer algorithms can conjure up pretty much anything on the screen in front of me. Consequently, there is a plausible—although not necessarily correct—explanation of what you are seeing, in contrast to what happens during a magic performance.22

An interesting illustration of this point can be found in a set of videos that create a strong magical experience even though no magician—at least, as traditionally construed—is present. In one such video, a man pours water into a glass, covers the glass with a piece of cardboard, and then turns the glass over while pressing the cardboard firmly onto the opening. He then places the upside-down glass on the table. Up to this point, it’s all just physics. The man then lifts the cup while making a quick twisting motion with his hand, and the water becomes suspended in the cup’s shape. You can clearly see a wobbly, jelly-like structure that immediately returns to its liquid state when touched.23

The first time I watched this video, I was very surprised. How is this possible? Doesn’t this defy all the known laws of physics? I was pretty sure that it must be a trick, but I could not think of a magic method that could create such a clean and beautiful illusion. The wobbly video was shot using a mobile phone camera, and the production value appeared to be pretty low. Surely, if the cameraman couldn’t hold the camera steady, let alone focus correctly, an amateur must have shot the footage. Because the video appeared to have been shot by an amateur, I did not suspect any fancy special effects, and based on the comments, neither did most of the other people who watched it.

It turns out, however, that the video was actually created using state-of-the-art editing techniques and was deliberately made to appear as if it had been shot by an amateur. In essence, the water trick illusion is fooling you twice. First, your perceptual system is fooled by the computer-generated special effects. But more importantly, you are also fooled into believing that the video is real. As such, you experience something that is apparently impossible, a situation very similar to that experienced when watching a magic performance.

Is Magic about the Supernatural?

As a magician and scientist, I’m often asked whether I believe in “real” magic, that is, forces beyond those known to current physics. This turns out to be a rather tough question to answer, because yes, I have seen a lot of things that I simply cannot explain. For example, I have no idea how a touch screen allows me to swipe from one page to the next, nor do I have a clue as to how each time I press a key on my keyboard, a letter appears on the monitor in front of me. Many of the technological devices we use today appear magical, but I know that they were created by very clever engineers using technology that is based on modern physics.24 I therefore don’t experience them as magic. Interestingly, there are phenomena that even the brightest minds struggle to understand. For example, how do your conscious thoughts interact with your physical brain? Philosophers and scientists alike struggle to explain this phenomenon, which on its face seems to be inexplicable in terms of current physics. Oddly, however, such phenomena are typically not considered to be magic.25 We will look at people’s beliefs about magic in much more detail in chapter 3, but let us now examine the role of supernatural powers in magic.

Any demonstration that appears to contradict our current understanding of science is generally considered to be magic. Indeed, the online Oxford Dictionary defines “magic” as “the power of apparently influencing events by using mysterious or supernatural forces.”26 We might, therefore, try to define magic—at least as performed by magicians—as the emulation of real supernatural powers.

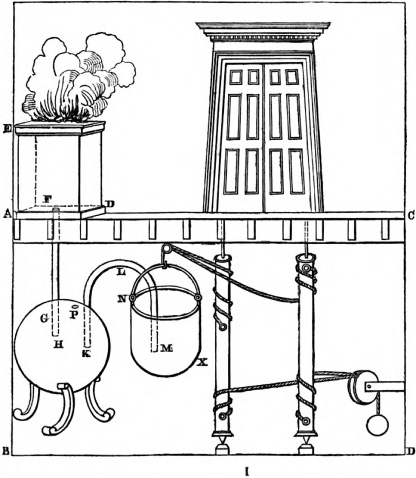

Many magicians use tricks and deception to create the illusion that they have supernatural powers, but they are generally considered to be charlatans. For example, some priests in ancient Greece and Egypt used sophisticated theatrical illusions to create the impression that they were in direct contact with the deities.27 For example, a priest might light a fire on an altar, after which a set of heavy stone doors would mysteriously open (see figure 1.3). These illusions provided powerful proof of the priest’s supernatural powers. But the true force behind this mysterious phenomenon was a clever array of counterweights and expansion tanks: A fire heated the water in a tank located underneath the altar, forcing it into an expansion tank. Once filled, the weight of the water inside the tank would pull open the doors. This clever mechanism was completely hidden, so witnessing the immensely heavy stone doors mysteriously open must have been an awe-inspiring phenomenon.

Figure 1.3 Ancient hydraulic mechanism that “magically” opens temple doors, as described by Heron of Alexandria (ca. 10–70 CE)

Similarly, many mediums today use magic tricks to create the illusion that they possess supernatural powers.28 For example, in 1974, Uri Geller caused a storm when he claimed that he could bend metal objects via the power of his mind and could read people’s thoughts. Some of these demonstrations were reported in one of the most respected scientific journals, Nature, but none of the claims stood up to scrutiny.29 It’s likely that Geller accomplished these feats by simply bending the objects with his hands and secretly peeking inside sealed envelopes.30

Most magicians, on the other hand, do not claim to have supernatural powers, and within the magic community, there has been a strong drive toward exposing those who make such assertions. In the 1920s, magician and escapologist Harry Houdini adamantly confronted people who claimed to have supernatural powers, and he spent much of his career exposing spiritual mediums.31 Indeed, magicians such as James Randi and Derren Brown have tried to expose Geller and others like him, and Brown has publicly explained how psychics use linguistic tricks and cold reading to give you the false impression that they know specific details about your life.32

Although magicians explicitly deny that they have supernatural powers, most magic performances evoke a sense of supernatural deception. For example, although Houdini adamantly attacked anyone who claimed to have spiritual powers, he was happy for people to believe that his super strength and skill enabled him to pick any lock and escape from any prison.33 Houdini was very proactive in creating this image of a man with near-supernatural powers, and although he was certainly skilled at picking locks, there was more to his escapes than meets the eye. Each of these stunts was a carefully choreographed performance that required meticulous planning, including the bribing of insiders, which created the illusion of Houdini’s ability to escape from anywhere.

Adamantly skeptical about any spiritual magic, Derren Brown claims that his illusions are created through clever psychological tricks. In one of his performances, Brown invites two members of an advertising company to a designated location, where they are asked to design a poster promoting a chain of stores.34 Before they start, he casually places a sealed envelope containing some of his own ideas in front of the men, who then come up with several drafts of their poster. To everyone’s surprise, Brown’s prediction is a good match. Most traditional magicians would leave it there, but Brown takes the illusion one step further by explaining that the advertisers had been unconsciously primed with that concept before they entered the room. We then revisit their taxi journey, which clearly depicts the two men driving past prominent objects that would later appear in their poster. This is presented as proof that Brown had purposefully primed the men to come up with that particular advertising concept.

Most people I talk to are convinced by Brown’s psychological explanations and don’t consider him to be a traditional magician. Without giving away the secret, I can assure you that the illusion described above did not involve priming or any other subtle form of mind control. (In chapter 7, we will examine the science behind this form of mind control in more detail.) This effect was created using more traditional magic methods. The real illusion involves you believing that these psychological effects are possible; Brown is honest about the tricks used by spiritualists, but he misleads you about his own psychological powers. The problem he faces is that mysterious psychological effects make his performances interesting and engaging. Thus, he endorses a new form of nonscientific phenomenon even as he dismisses the occult. Brown has stated that he struggles with this paradox, but it’s a paradox that all magicians face: magic is only magical if the audience experiences the effect as mysterious, surprising, or supernatural.35 Although magicians explicitly deny these supernatural explanations, our experience of enchantment nevertheless depends upon those explanations.

Is Magic about Suspension of Disbelief?

When I ask magicians to define magic, they often talk about “suspending your disbelief.”36 Suspension of disbelief is a concept that is often used in theater, which might explain why magicians relate to it. For example, every time you go to the theater, you accept the scenes being acted out on stage as real. You are fully aware that an actor on stage is simply pretending to cry, but by suspending your disbelief, you can enter this world of fantasy. Likewise, when Peter Pan is lifted by steel cables above the stage, you suspend your disbelief and imagine that he is truly flying, regardless of whether or not you can see the cables.

Although a play may appear magical, it is a different type of experience from that encountered when the magician David Copperfield flies across the stage. Seeing strings attached to Copperfield would destroy the illusion, because you are no longer experiencing the impossible.37 In fact, even suspecting the existence of strings destroys the illusion, and this is why Copperfield flies through hoops and is locked inside a transparent box, while still apparently defying the laws of gravity. Good magic happens regardless of whether or not you are willing to suspend your disbelief. This is why Teller—the silent guy from Penn & Teller—argues that experiencing magic is an unwilling, rather than a willing, suspension of disbelief. According to him, magicians force you to suspend your disbelief, regardless of whether or not you want to do so.38

Although we are getting closer to understanding what magic is, the suspension of disbelief idea does not fully capture people’s experience of witnessing a magic trick. When I see David Copperfield flying across the stage, I don’t truly believe that he can actually fly. In fact, if I believed that people can fly, I would no longer experience this performance as magical.39 Surely then, magic is about experiencing things that we think are impossible, or what Darwin Ortiz refers to as the “illusion of the impossible.”40

Is Magic about Conflict between Belief Systems?

Jason Leddington, a young philosopher at Bucknell University, suggests that suspension of disbelief is not the key to magic. Rather, “the audience should actively disbelieve that what they are apparently witnessing is possible.”41 In other words, magic is only successful if people simultaneously believe and disbelieve what they are seeing. In this view, magic creates a conflict between what Darwin Ortiz calls our “intellectual belief” and our “emotional belief.” Your intellectual belief tells you that magic is impossible, but on a more primitive emotional level, the performance induces a belief that magic is actually happening.42

Leddington connects this with a philosophical idea proposed by Tamar Szabó Gendler: the concept of alief. An alief is an automatic, primitive attitude that may conflict with a person’s explicit beliefs. Whereas most of you will be familiar with beliefs, the concept of alief may need a bit more elaboration. Let us consider the following example: In 2007, the Grand Canyon Skywalk opened on the Hualapai Indian Reservation, promising a sensation that, until then, one could only experience in dreams. One tourism website promises that “dreams and reality will meld into one,” which immediately conjures up expectations of shamanistic experiences of all sorts. However, this dreamlike experience could not be further from spirituality. The Skywalk simply consists of a horseshoe-shaped glass walkway that protrudes seventy feet beyond the canyon’s rim, thus offering stunning views of this marvel of nature. It allows you to stand over the canyon and look down through the crystal-clear transparent floor, leaving you with the feeling of being freely suspended more than two thousand feet in the air.

Leddington suggests that walking onto this viewing platform elicits a feeling that is comparable to experiencing a magic trick because, like magic, it creates a tension between our beliefs and our aliefs. The Grand Canyon Skywalk is safely secured, and the glass has been heavily reinforced and is thus extremely unlikely to break. Even though thousands of people have ventured onto this platform before, the physical process of leaving the hard ground of the canyon rim feels uncomfortable. Indeed, you can see people clinging to the railing, and they hesitate before stepping onto the transparent part of the walkway. The strange sensation that you feel when stepping out onto such a platform is created by the tension between two competing beliefs: “Although the venturesome souls wholeheartedly believe that the walkway is completely safe, they also alieve something very different. The alief has roughly the following content: ‘Really high up, long long way down. Not a safe place to be! Get off!’”43

According to Leddington, the experience of magic results from a similar cognitive process. The audience knows that magic is impossible, yet a good magic performance simultaneously induces the belief on a more primitive and emotional level (alief) that the impossible is indeed happening. Leddington’s philosophical theory has only just been published, but it has already attracted much interest from magicians, philosophers, and psychologists.

Is Magic about Impossibility?

Most theories of magic assume that it involves experiencing something impossible. Indeed, I have titled this book Experiencing the Impossible, as this feels like an intuitive way to capture the emotional sensation that magic elicits. But what does it mean for something to be impossible? Exploring this perspective may give us some additional clues about the nature of magic.

The term “impossible” refers to something that is not possible. This differs from something that is extremely unlikely. It is extremely unlikely that I will win the lottery, but there is still a slim chance that this could happen. On the other hand, most people would consider it impossible for me to levitate my laptop—gravitational forces pull objects to the surface, and without a counterforce (e.g., magnetism), objects simply cannot levitate. Logically speaking, the term “impossible” does not allow for degrees, any more than does “contradictory.” And yet, some things seem to be more impossible than others. How could this be?

Walt Disney was one of the world’s most successful cartoonists. In his early days, his cartoons were rather surreal, depicting a world where anything was possible: a sausage could jump from the grill and dance in a kick line. However, Disney’s more successful feature-length films followed specific magical rules whereby magic needed to be “plausibly impossible,” meaning that it could violate some real-world expectations but not too many.44 For instance, in the movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, it is plausibly impossible for forest animals to communicate with Snow White but implausibly impossible for them to double in size or to ooze through keyholes.

Andrew Shtulman suggests that in a fictional narrative where everything is possible, we still distinguish between events that are flat-out impossible and those that are impossible but plausible.45 Shtulman points out a few examples. In Star Wars—Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back, the Jedi master Yoda teaches his apprentice, Luke Skywalker, to levitate stones before teaching him how to levitate an entire starship. Likewise, in the magical world of Harry Potter, the potions instructor Severus Snape teaches his students how to brew a forgetfulness potion before he teaches them how create a potion for endurance. Similarly, in the fictional world of Disney’s Cinderella, the fairy godmother turns a pumpkin into a stagecoach and a horse into a coachman rather than turning a horse into a stagecoach and a pumpkin into a coachman. In the real world, rocks are lighter than starships, your ability to bear prolonged hardship requires more mental effort than simply forgetting something, and pumpkins show more resemblance to coaches than to coachmen. These perceptual and conceptual considerations influence your judgments in the real world, yet they should not do so in the world of magic.

Shtulman asked people to review the curriculum from Harry Potter’s Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and evaluate the difficulty of various pairs of spells (e.g., levitating a bowling ball versus levitating a basketball). In each pair, both spells violated the same causal principle (i.e., gravity) but differed in terms of their subsidiary principle (e.g., weight). Interestingly, spells that violated deep-seated causal principles and seemed implausibly impossible were rated as harder to create than those that were considered to be plausibly impossible. In other words, even in a world where nothing is impossible, some things are perceived as being more impossible than others.

Does Magic Have a Neural Basis?

Now that we have dealt with some of the philosophical and psychological perspectives relating to magic, let us turn to neuroscience. Nearly a decade ago, Benjamin Parris and I tried to discover the parts of our brain that are involved in experiencing magic.46 This was at a time when scientists still got excited by demonstrating how certain parts of your brain light up when you have a particular thought or carry out a particular task, and we both joked that we could call this theoretical brain region the “magic spot.”

We didn’t have any official research funding for our quest, and we were therefore forced to turn my bedroom into a temporary film studio, where we recorded different magic tricks. We played video clips of these tricks for our participants while measuring their brain activation using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan their brains (not in my bedroom). The participants also viewed clips of me doing things with the same objects that did not involve magic but were still surprising. This provided us with a baseline to which we could compare our participants’ brain activation.

The results took us both by surprise. Even though we had both joked about hoping to find the magic spot, neither of us seriously believed that magic could be localized to one discrete area because magic involves many different types of experiences. However, to our amazement, once the large amounts of data were processed, we found that two brain areas became particularly active at the moment when participants viewed the magic tricks: the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and an area known as the anterior cingulate cortex. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is involved in monitoring conflict. Likewise, the anterior cingulate cortex is a part of the brain that tries to resolve conflict. To our surprise, magic activates those parts of the brain that are typically involved in processing and resolving more general types of cognitive conflict.

Figure 1.4 Brain activation when people watch a magic trick (adapted from Parris et al., “Imaging the Impossible”)

Our paper reporting these findings, which we titled “Imaging the Impossible,” was the first neuroscientific study to explore the neural mechanisms underlying our experience of magic. Since then, others have conducted similar studies and have come to similar conclusions.47 Then, as now, we did not believe that this or any other neuroscientific study would tell us what magic is. However, it is interesting that observing magic and dealing with other types of conflict both activate the same neurons. This indirectly supports the idea that magic involves a conflict between what we believe to be possible and what we believe we have seen.

Magic as a Kind of Wonder

At this point, I would like to sum up what we have learned so far about magic. We have learned that magic creates a cognitive conflict between things we experience and things we believe to be impossible. But it is not simply about experiencing things that are impossible; instead, it is about experiencing things we believe to be impossible. More precisely, my colleagues and I propose that magic is the experience of wonder that results from perceiving an apparently impossible event.48

In this view, at the center of the magical experience lies a cognitive conflict, and the stronger the conflict, the stronger the experience of magic. There are three important things that are worth pointing out. First, magic depends not on what you have actually seen but on what you believe you have seen. This might seem like a subtle distinction, but most techniques in magic involve not simply creating an event but manipulating your beliefs about that event. (We will discuss this in more detail in the next chapter.) Second, because the cognitive conflict also depends on things that we believe to be impossible, rather than things that actually are impossible, people with different beliefs will experience magic differently. Put simply, a mind-reading demonstration will elicit wonder only if you do not believe in telepathy. Third, because we are interested in what people believe to be impossible, we need not restrict ourselves to logical characterizations of impossibility; you can have a stronger or weaker belief in an event’s impossibility regardless of whether or not it is actually impossible. Thus, magic can vary in its intensity. For example, although the laws of physics dictate that it is impossible for any object to just disappear, I intuitively believe that it is more impossible for a larger object to disappear than a smaller one; a disappearing elephant will create a stronger magical experience for me than a disappearing mouse. Only time will tell whether this framework holds up, but for the moment, I believe that it can explain much of the experimental evidence collected to date. Let us now look at how this framework helps explain why we all experience magic differently.

Do We All Experience the Same Magic?

If magic relies on a conflict between what we believe is possible and what we perceive, people who hold different beliefs could experience the same magic performance in very different ways. For example, young children tend to blur the boundaries between reality and fantasy and often believe in ideas and concepts that we adults dismiss as being impossible—for example, magical creatures, such as Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy, and the idea that you can truly make things invisible.49 Jay Olson, a PhD student at McGill University, recently conducted a study on how children interpret magic tricks.50 He filmed a simple trick in which a magician used sleight of hand to make a pen disappear. In the video, the magician held a pen between his hands and suddenly appeared to break it in half; when he opened his hands, the pen had vanished. The secret behind this trick is that the pen was quickly moved inside the magician’s jacket. Olson wanted to see how children of different ages would explain the trick; he even provided clues as to how it was done. Anyone watching carefully would notice an object hitting the magician’s shirt, which clearly hinted at the method.

Olson and his fellow researchers played this video clip to nearly 170 children between the ages of four and thirteen years and asked them to explain what they saw. Younger children (four to eight years old) typically took the magician’s actions at face value and claimed that the pen “just disappeared” or simply “dissolved in the magician’s hands.” Older children (seven to nine years old) developed possible yet still implausible explanations of the trick. For example, although the magician had rolled up his sleeves, many suggested that he had hidden the pen up his sleeves or in his skin. My favorite explanation was that the magician’s torso was actually a mannequin and that the magician hid the pen inside the empty torso. These findings demonstrate that as children discover more about the world and learn to distinguish between appearance and reality, they start to interpret magic tricks in less supernatural ways.

Conversely, there are magic tricks that will amaze adults but leave young children cold. This is because adults generally make different assumptions about the world. When we see an object occluded by another object, we typically assume that the first object continues to exist and retains its physical properties; we fully understand that objects continue to exist even though we may not see them. This principle, which the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget called object permanency, allows us to experience a stable world—a world in which objects stick around even when they are out of sight.51

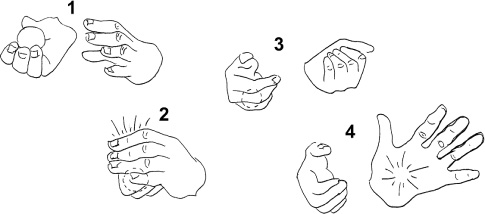

Much of magic involves exploiting assumptions we make about the world, and there are countless magic tricks that exploit object permanency.52 For example, in the French Drop, one of the most common sleights of hand used to make a coin disappear, the magician pretends to transfer a coin from one hand to the other, when in fact the coin remains secretly concealed in the original hand (see figure 1.5). After this simulated transfer, the magician pretends to hold the coin and, even though you cannot see it, you are convinced that it must still be there. After a few moments, the magician opens his hand to reveal that the coin is no longer there—it has vanished!

Figure 1.5 French Drop: Sleight of hand, used to vanish a coin. The spectator assumes that the coin has been transferred from the magician’s right hand into the left hand, when in reality it remains secretly concealed in the right hand.

This simple yet extremely effective coin trick relies on your sense of object permanency. Thus, even as object permanency allows you to experience a stable world, it is also responsible for fooling you into believing that a coin can simply vanish. Most importantly though, it allows you to experience a conflict between your beliefs (i.e., the coin is still in the hand, even though I can’t see it) and your experience (i.e., the coin is no longer there).

How then would a young child respond to this trick? To answer this question, we must look at young children’s beliefs about the world. We are born into a very confusing world that is full of overwhelming stimulation and information. Much of our early development involves gradually learning to make sense of the things that are happening around us. Piaget suggested that babies spend their first two years learning about the existence of objects, and he argued that before this step is reached, children consider objects that are out of sight to be nonexistent. There is currently no consensus as to when exactly object permanency develops; although Piaget initially argued that this does not take place until eight to twelve months of age, others have suggested that even fourteen-week-old infants may have some form of object permanency.53 Even though there is still much disagreement as to how and when object permanency develops, it is clear that young infants’ ability to represent and reason about unseen objects is significantly limited and that our sense of object permanency develops through infancy and childhood.

It is this weaker sense of object permanency that explains why babies all around the world are fascinated by peekaboo. To play this game, all you need to do is hide your face for a few seconds and then simply pop back into view and say, “Peekaboo!” As an adult with a fully developed sense of object permanency, we may find it hard to appreciate why babies are so drawn to this game. Early theories of why babies enjoy this game so much assumed that they are simply surprised when the face returns to reality.54 It was thought that peekaboo creates surprise, similar to the element of surprise in a joke or a magic trick. However, it turns out that there is more to peekaboo than simple surprise because infants don’t enjoy the game if you include too much magic. W. Gerrod Parrott and Henry Gleitman have shown that babies get less enjoyment from the game if you surreptitiously change the person who reappears.55 Adding too much surprise seems to kill the game, and it is thus thought that peekaboo helps babies test and retest the fundamental principle of object permanency. In other words, this simple game may teach babies that things may stick around even though they are out of sight. Given that young children have different beliefs about the world, we can assume that they will experience magic tricks differently than we do.

Piaget conducted most of his early research on his own kids. He gave them puzzles and observed the types of mistakes that they made at different stages in their lives. Given our shared Swiss heritage, I was very keen to emulate Piaget by running experiments on my own children, and many of the experiments involved studying how they responded to my magic tricks. My older children were often amazed when I vanished objects using the French Drop, but my youngest daughter, Mae, who was one year old at the time, was far from impressed. Because babies can’t talk, it’s difficult to ask them what they think of a trick, but you can gauge their experience simply by monitoring their emotional reaction. It’s fair to say that Mae was far more engaged by peekaboo, whereas most of my sleight of hand magic left her pretty cold. This, of course, is not that surprising, because at the time, Mae’s sense of object permanency was still developing and, for her, the existence of objects that were out of sight was far hazier. Simply making something disappear would not result in a strong cognitive conflict between what she saw and what she believed about the world, and so she would not experience the magic.

It goes without saying that experiencing a magic trick relies on the spectator not discovering the true method behind the trick; once you have discovered the secret, the cognitive conflict disappears. One of the magician’s primary goals is to avoid anyone noticing how the trick is done, which was why I spent nearly every free minute of my teenage years practicing sleight of hand and ensuring that nobody would ever notice when I palmed a coin. Many of my friends and colleagues often comment on how much my children must enjoy having a dad who can perform magic, and being a magician certainly comes with some parenting perks. For example, my children get very excited when I magically pull sweets and coins from behind their ears. Because I have spent a large part of my life dedicated to perfecting my legerdemain, I have always felt that my conjuring skills are superior to those of most mums and dads. However, I soon realized that I was deluding myself. One day, when my oldest daughter, Ella, was four, she came back from nursery school telling me that her teacher was also a magician. I knew that he was not a proper magician, but in my daughter’s eyes, there was very little difference between Ed’s simple magic tricks and my sleight of hand illusions. Had I lost all of my skills and truly misspent my entire youth?

Just because a child has been fooled by a trick does not necessarily mean that adults won’t discover the secret. In fact, adults often discover the secret behind the magic tricks performed by children’s entertainers, and most children’s tricks will fail to amaze a skeptical adult audience. This is not because children’s entertainers are bad magicians; it’s simply because their tricks are designed to be enjoyed by children rather than adults. Why then are children more easily deceived? We have run experiments in which we measured participants’ eye movements to study differences in the attentional strategies that children deploy when they see a magic trick.56 We used a specially designed magic trick in which I vanished a lighter by using misdirection. We will discuss this type of magic trick in much more detail later on, but the method behind this trick uses misdirection to draw attention away from the lighter, which enabled me to drop the lighter into my lap. Although this happened in full view, the misdirection prevented most people from noticing the secret. We asked adults and children under the age of ten to watch a video clip of this trick while we monitored where they were looking using an eye tracker. Our results showed that children had far less control over where they were looking and were much more easily misdirected. These results further illustrate that our experience of magic tricks is very subjective and that children and adults can clearly experience the same performance very differently.

Because all of us have very different beliefs about what is possible, we will all experience magic slightly differently. However, inasmuch as magic is about experiencing more general cognitive conflict, it should be possible for nonhumans to experience similar emotions. In recent years, there have been several viral YouTube videos showing how animals react to magic tricks. For example, Jose Ahonen, a Finnish magician, gained a worldwide audience through a video clip entitled “Magic for Dogs,” in which he uses sleight of hand to vanish dog biscuits.57 Once the dogs realize that the biscuits have vanished, they appear genuinely puzzled and confused, similar to how humans react to magical illusions. By now the internet is full of videos of magic tricks being performed for all sorts of animals, and even though it is difficult to know what these animals are experiencing, their reactions suggest that we may not necessarily be alone in enjoying these enchanting illusions.

Magicians have astonished people with their illusions for thousands of years, and they can explain the methods used to create the illusions in much detail. There are thousands of magic books that provide intricate details about how these tricks are performed, but far less is known about the experience they elicit. The combined efforts of magicians, psychologists, philosophers, and neuroscientists are helping to shed light onto this experience. Magic is an experience of wonder that results from a cognitive conflict between things we experience and things we believe to be impossible. However, because we all hold different beliefs and experience the world differently, each magic trick will elicit a somewhat unique emotional experience. Let us now take a closer look at how and why our brains are so easily tricked into believing that we have experienced something that we believe to be impossible.