THE VERNE EFFECT

To further underscore the impact of being able to conceptualize and to understand something about future viewing, one needs to look at those who have come before. None so readily exemplifies future viewing, or predictive paranormal functioning, as Jules Verne.

Jules Verne in 1863 began writing with intriguing detail about things to come. In great detail, he described the inventions of tomorrow. He projected cities, places, and things from his imagination, things that were not yet a reality in his time.

Within a single novel, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, he foresaw the full development and impact of the submarine, the aqualung, fully automatic rifles, television, and space travel. He described recessed and indirect lighting, extensive use of fish farming, night vision devices, the electric clock and cooking, salt-water distillation using electric current, the idea of twin-hull designs, even the lock-out chamber now functional on nearly all production submarines.

Where did all this information come from? Certainly, his ideas far outstripped what was commonly known at the time that he was putting them on paper.

The actual concept of a submarine wasn't unknown. It had first been envisioned by an English mathematician named William Bourne in 1578. Cornelius Drebbel constructed a craft capable of submerging and resurfacing in 1620. And the first successful use of a submarine as a warship occurred in 1864, when the Confederate craft Hunley blew up the Federal corvette Housatonic in the Charleston Harbor on February 17, 1864. All of this occurred six years before his book was published. One might therefore argue that his future envisionments of the submarine were really good guesses, information extrapolated from what was already known. Or was it?

When you read his book, you quickly find that it isn't just the mention of a submarine that brings power to his predictive writing. He puts the submarine solidly within the context of a complex social structure and society, from which he then draws many other predictive objects, events, and conclusions. He thoroughly describes the details surrounding the times, which allows for a complete understanding of his concepts and ideas, as portrayed through his major characters.

Was he discerning objects and events not yet relevant to history—was he being clairvoyant? Or, was he stepping into the future with his mind and seeing that which was yet to come? Was he remote viewing?

Skeptics who are still arguing over the veracity or reality of remote viewing might call his predictions luck. This is not a surprise.

Lead-sealed targeting envelopes stored in private safes, a metanalysis of dozens of independent scientific studies, hundreds of evaluations, an entire army of scientists and oversight committees focused on providing protection against fraud, and periodic reviews for over a twenty-five-year period cannot seem to persuade those who will always find a reason to doubt the existence of the paranormal.

However, over the course of my experience within the classified remote viewing project, there are literally hundreds of examples of future targets (objects, events, or locations) that, in effect, didn't yet exist when the remote viewing material was created, assessed, and analyzed. In some cases, these targets could not even be verified as "coming into existence" for a period of nearly two decades. Why? Because they existed only in the future.

A few examples of such targets taken from the STARGATE files follow:

–The predicted launch date for a newly constructed submarine-110 days before it actually rolled from its construction crib and into the harbor.

–The predicted release of a hostage in the Middle East and a correct description of the medical problem precipitating his release. This information was provided three weeks prior to even the hostage takers knowing what they were going to do.

–A prediction of an attack on an American Warship: the location, the method, and reason for the attack—three days prior to the attack taking place.

When remote viewers look into the future, they can actually capture the energy, feelings, and concepts, and paint them on the canvas of our minds.

I've italicized concepts here, because this is probably the most important thing a remote viewer can perceive.

As I've discussed previously, concepts are what integrate or tie the details of our visions together. They help us to understand what is going on in a different place in time, long before we ever get there. Concepts interconnect and weave the social and physical aspects of future sight into a framework or context that can be more easily understood by those of us trying to understand what a future prediction might mean.

Jules Verne was probably doing excellent remote viewing when he described the drive unit for his submarine in

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. All we have to do is emulate his work and look ahead ten, twenty, even seventy-five years, to pick and choose among the already existing miracles of technology. Sounds easy. But is it?

I believe Jules Verne discovered very early on that understanding the conceptual framework was even more important than the details within his predictive perceptions. It is these very concepts that he brings to us in his writings that continue to amaze readers even today. He made the future so clear for us.

He also put the readers where they could imagine themselves to be. He never took us into the future, he brought the future back to us. He did this with a positive and creative impact, which we still feel today.

Jules Verne was born in Nantes, France, on February 8, 1828, and he died on March 24, 1905. Much to our benefit, in a period of less than a dozen years (1863-1874), he laid much of the foundation for what we know today as Modern Science Fiction.

Following his first acclaimed success (the novel Five Weeks in a Balloon), Verne presented a new manuscript to his publisher. The title of the manuscript was Paris in the

Twentieth Century (1863). But Verne's publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, was disappointed. In his own words: "I did not expect something perfect. But I expected better. My dear Verne, if you were a prophet, no one would believe your prophecies today."

The publisher warned that attempting to publish this new manuscript would be "a disaster" for both of them.

What were the prophecies that caused such a negative reaction? Why wouldn't the publisher produce his manuscript? Some of the details Verne provided in his new manuscript spoke about the year 1960. In it, he described travel by subway, gas-driven cars (the combustion engine was not built until 1889), communication by fax and telephone, the use of calculators and computers, and electric concerts providing entertainment. In his manuscript, he talked about a world in which everyone can read, but no one reads books!

Latin and Greek are no longer taught in schools, and the French language has been filled with very "disagreeable"

English words. Society is dominated by money, and the homeless walk the streets. It is a police state run by bureaucrats. He imagined streets overrun with lights and electronic advertisements. He even predicted the invention of the electric chair (which didn't appear until 1888).

Where did these ideas originate? Did he actually go into the future and see what was going on? Or, by envisioning such a future, did he have a hand in creating it? What if the imagination, the seat of creativity deep within the mind, is directly connected to what we might call "the eventuality of truth?" What if humankind is connected in a some psychic way with what is eventually going to happen?

In other words, what if we are capable of seeing or envisioning what we (humankind) will eventually experience? If this is so, then our perceptions of the future and all that it holds in store for us become an exciting, dynamic, and interactive adventure. We become the ultimate time machine, the ultimate traveler in time, by virtue of our ability to simply conceptualize it.

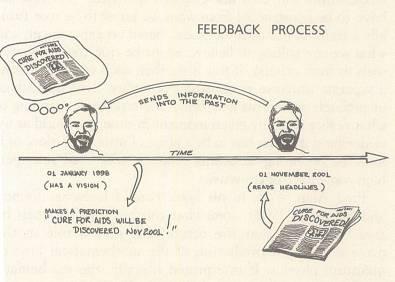

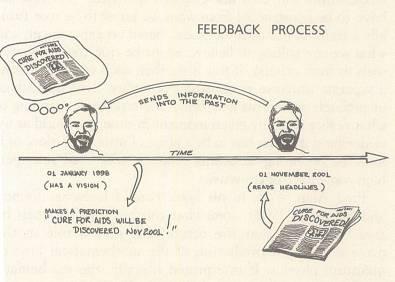

For a while, the scientists studying remote viewing hypothesized there might be a way that information could be passed to us—by us. One of the things they noticed was that post hoc feedback about the target and the results of the remote viewing seemed to have a dramatic effect on the percentage of time a remote viewer was right about a target, or the amount of information that could be collected or stated correctly.

A rather simplistic example of how this might happen is as follows.

On January 1, 1997, we envision an event. Let's say it is the discovery of a cure for AIDS. In our vision, we see a stark announcement in three-inch black letters embossed boldly across the headline of a newspaper—CURE FOR AIDS DISCOVERED! In our vision on the upper right-hand corner of the same newspaper, we see that the date is sometime in November of the year 2001. We write about it, and it is published as a "prediction." An incorrect term in all probability, but nevertheless, it is published.

A few years have now gone by, and we've forgotten about our vision. We are on the way to work and we stop by the newspaper kiosk and buy a copy of the local newspaper to read while on the train to work. Once comfortable in the train seat, we pull the paper from our briefcase and snap it open to the front page. There, embossed across the front page in bold black letters is the statement—CURE FOR AIDS DISCOVERED! Our reaction is to quickly glance at the upper right-hand corner of the paper, where we see the date, November 1, 2001.

The first assumption by most readers is that this is a correct "prediction." What the scientists hypothesize is that at the moment of cognition—where we suddenly understand a cure has been found—we actually send the information to ourselves in the past!

It is a full loop of cognitive communication. The entire communication, from when we first made the prediction until our complete feedback has all essentially taken place within ourselves. It is actually a complete event (except for the beginning—a remote viewing and the end—sitting on a train and reading the paper) that we experience outside of space and time, or within our minds.

While this view held sway for many years within the research community, at least with some of the scientists, I'm not so sure this is what was happening with Verne, nor with remote viewing. The counter argument is simple. Jules Verne died before he received feedback on most of what he predicted. So there must be something else going on here.

As a long-term and experienced remote viewer, it is my belief there are other possibilities to explain what is going on. These need to be examined.

Reality Constructs

What comes first, the chicken or the egg? The vision or the reality? My own perception is that reality is always a construct that first begins in the mind. It is a construct born from both my belief as well as my knowing. Philosophically, and as I've previously argued, one could state that we can never really know what someone else knows. We can only believe what they are telling us. Simply put, we are each stuck within our own universe of experience. Our realities have to be constructed from what we know to be true (usually a result of our own judgment, based on experience), and what we are willing to believe might be true (beliefs shared with us from others). If this is so, then each of us represents a separate universe or construct of reality. Because each of us probably represents a separate universal understanding of what reality is at any given moment in time, the world as we understand it either has to be a place of utter confusion, or it must be operating according to some additional rule, perhaps some form of consensus.

Fred Alan Wolf, in his book Parallel Universes (Simon and Schuster, 1988), somewhat touches on this when he says: "The fact that the future may play a role in the present is a new prediction of the mathematical laws of quantum physics. If interpreted literally, the mathematical formulas indicate not only how the future enters our present but also how our minds may be able to 'sense' the presence of parallel universes." He goes on to state, "The laboratory of parallel universe experimentation may not lie in a mechanical time machine, a la Jules Verne, but could exist between our ears."

To observe the truth in these statements, you only have to observe the people around you. You will see that some people are willing to believe in almost anything, while others believe in almost nothing they haven't touched, tasted, or personally observed. Some are viewed as reasonable in what they believe, but this is only because they fall within an acceptable line or boundary of agreement that's socially acceptable. Many are easily lured across this line into thinking they know something they don't, while others are quick to believe in anything, and are rather fixed with regard to what they actually know, or think they know. What is important here is the distinction that while we live in a multiple-reality universe, it is up to each of us to determine where we will draw the line between believing and knowing. So whether or not we like it, by its very construction—reality then becomes both a place of consensus as well as individuality. The degree to which we are allowed our individuality is dependent on the degree to which we are willing to accept personal responsibility for our own beliefs, thereby consciously affecting the consensus.

The kicker is that this consensus is probably an unconscious consensus and not a conscious one. That would seemingly agree with C. G. Jung's ideas surrounding the collective unconscious.

How This Might Work

In reality, at least as I envision it, most of what happens is based on an assumed order. For lack of a better word, I will call this assumed order the Unconscious Consensus. For the most part, we spend a great deal of time within our reality focused only on those things that directly affect us: finding a parking space for our car, shopping, studying, working, or being involved in the myriad relationships that are closest to us. These are certainly important issues for us in a personal sense, but within the larger view—or within the overall reality of our world or where it might be going—we are essentially turning over our personal responsibility toward creating the future to the "assumed order" or the Unconscious Consensus. So the world moves merrily along its path and we are subject to edicts by the Unconscious Consensus, which constitutes our overall reality construct.