If I had a gun for every ace I’ve drawn

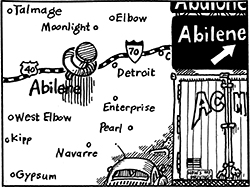

I could arm a town the size of Abilene1

Don’t you push me, baby, ’cause I’m moaning low

You know I’m only in it for the gold

All that I am asking for is ten gold dollars2

I could pay you back with one good hand

You can look around about the wide world over

You’ll never find another honest man

Last fair deal in the country, sweet Suzy

Last fair deal in the town

Put your gold money where your love is, baby

Before you let my deal go down

Don’t you push me, baby

because I’m moaning low

I know a little something

you won’t ever know

Don’t you touch hard liquor

just a cup of cold coffee

Gonna get up

in the morning and go

Everybody’s bragging and drinking that wine

I can tell the queen of diamonds by the way she shine3

Come to Daddy on an inside straight4

I got no chance of losing this time

No, I got no chance of losing this time

Words by Robert Hunter

Music by Jerry Garcia

Abilene, Kansas (present population 6,242), was settled in 1858.

. . . it became the first railhead of the Union Pacific Railroad at the N terminus of the Chisholm Trail from Texas (1867–71) at a leading distribution point on the Smoky Hill Trail to the West. One of the most famous of the wide-open cow towns, it was “cleaned up” by Wild Bill Hickok, who became its marshal in 1871. (The Cambridge Gazetteer of the United States and Canada)

Abilene, Texas, founded in 1881, was named for the Kansas town because it was also a railhead for cattle drives. When Hunter speaks of a “town the size of Abilene,” we can assume he meant the Kansas town at the height of its “wide-open” period, ca. 1870. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the town was first known as Mud Creek, and was named Abilene around 1860, for the biblical Abilene, which means “grassy plain.” The Britannica also gives a clue to the town’s population at its height, noting that “the biggest year of cattle drives to Abilene over the Chisholm Trail was 1871, when more than 5,000 cowboys driving 700,000 cows arrived at the yards.”

“Abilene,” by Lester Brown and Bob Gibson was recorded by Gibson in 1957).

The gold dollar coin referred to in the song may have been of several possible designs: The 1849–54 Liberty Head; [1854-56] Small Indian Head; the 1856–89 or the 1856–89 Large Indian Head.

In divination with cards, this card indicates a flirtatious, sophisticated, witty, fair-haired woman.

In this reference, “the way she shine” may refer to a marked card needed to complete the following line’s inside straight.

An inside straight is a drawing hand in poker with a single missing rank to draw a straight. A hand with an ace, a king, a jack, and a ten would need a queen to fill an inside straight. This is how the player knows he will not lose, the card on the top of the deck has the shine of the queen of diamonds, so he knows he will make his hand, even though it is a statistical long shot. Good poker players will almost never draw to an inside straight.

Studio recording: Garcia (January 1972).

First performance: February 18, 1971, at the Capitol Theater in Port Chester, New York. It remained in the repertoire thereafter.

Gambling

A function of Art is to preserve tradition and evoke strong associated affect. A picture may tell a thousand words, but a single word can also stand for a picture. The lyricist choosing the word or tersest phrase can evoke allusions plumbing deep-seated emotions.

Words connected with gambling have a long tradition and drag in their trail romantic associations tied to the Wild West frontier—a frontier now gone, in fact, but a concept that we try continually to re-create in film, music, painting, and some types of play. In lyrics, the Old West of drifters, free spirits, living by one’s wits and fists, and traveling light, come alive. Truckin’, gambler, ace, bluff, raise—place-names such as Abilene, Deadwood, Texas—each immediately conjures a past time in a newly opened country.

Ironically, a recent burst of interest in poker, now omnipresent on TV and the Internet, is a dark mirror image of what poker in song and the West represented. Song celebrated the desire to quit the safety of home, family ties, traditional job—the romance of being on the road with no specific direction and taking your chances in the next saloon with a poker game running. Ballads celebrated whisky and wild women and staking it all on a single hand, celebrating the illusion that one good hand will make your fortune forever—the universal fantasy of every gambler. (“Loser “—“I could pay you back with one good hand.” “Ramble On Rose”—“Sittin’ plush with a royal flush”). But winning can also be beside the point. It’s the action that counts. “Stella Blue” evokes endless nights in every “blue-light cheap hotel”—unable to win but keep on bucking. There is the old classic joke about the cowboy who plays in a game he knows is fixed. When asked why he plays in a game he can’t beat, his response is, “It’s the only game in town.”

That was then—play for the high, not the money. Compare that with playing on the Internet from the comfort and safety of your own easy chair—no road, no wild women, and in lieu of whiskey, a backup computer to figure the odds on each hand. Nerds fighting with computer programs—no six-guns. Or competing in casinos with thousands in a single tournament, many playing as partners. Not the image of the lone rider braving Dodge to take on the other passing strangers. Co-opted by large corporate interests, all is safe, sanitary, secure, even respectable—you might as well be at home. (Throwing Stones—“Commissars and pinstripe bosses / Roll the dice.”)

Gambling and the potential for danger—violence—had always been part of the spice. “Mississippi Half-Step” takes it back to Cain and Abel, citing loaded dice and an ace behind the ear as motivation for the “first murder.” The World Series of Poker, which started the current craze, was created by a man twice indicted for murder, Benny Binion, who fled Texas to the safety of Las Vegas and filled his game with “West Texas” gamers. Now a mere curse word in a casino will get you suspended from play.

Twenty years ago, when I started playing with the big boys, poker was still pretty wide open—cussin’, fistfights, whisky, cigars, wild women, and all of it face-to-face. I got the moniker “Deadman” because of my association with the Grateful Dead, but also because when I won my World Series Championship bracelet, the loser held aces and eights, known as the “dead man’s hand,” as Wild Bill Hickok held when shot to death in Deadwood. Today, I doubt that many poker players know about Hickok, Deadwood, the frontier, or give a damn. They are chasing dreams of money on a new variety of the spinning wheel. Poker, with its huge number of participants, has reduced the value of skill, increased the factor of random luck, and come closer to roulette or the lottery.

So where is the outlaw mystique of the game now? In the songs, in the pages of this book. Balladeer sing on!

—Hal Kant, General Counsel to the Grateful Dead, 1970–2000

Studio recording: Garcia (January 1972).

First performance: February 18, 1971, at the Capitol Theater in Port Chester, New York. It remained in the repertoire thereafter.