Publisher’s Note

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was an explosion of newspapers, periodicals, and books. Several factors provided the impetus for this: The rise of the middle class assured a literate and affluent audience; improved transportation systems made widespread distribution possible; and the nineteenth century saw enormous technological advances in printing.

This printed material informed and entertained, just as films, radio, television, and the Internet would do in later decades. A large part of the appeal of this—the first mass media—were the illustrations it offered. Like later media, it influenced, as well as reflected, the society it served. In the 1880s, Kate Greenaway’s drawings of charmingly clad children caused a minor revolution in children’s fashions; Charles Dana Gibson’s “Gibson Girl” created the ideal for young women of the Gilded Age; the paintings of Jessie Willcox Smith served as the standard for American children of the teens and twenties; and the nurseries of Great Britain were filled with the tea sets, dolls, calendars, and prints of Mabel Lucie Attwell.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the primary method of reproducing pictures was wood engraving, developed by Thomas Bewick in the latter half of the eighteenth century. In this process, the image was drawn directly on the wood block, then carefully cut away by the engraver. The process was slow; the size of the art limited, and reproduction was in one color only. In the 1850s, Englishman Edmund Evans developed a method of wood engraving that allowed for multi-color printing, and many of Evans’ artists—Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, and Kate Greenaway—enjoyed enormous success. The invention of photography further advanced the printing process. By the beginning of the twentieth century, lithography had replaced wood engraving as a method of reproducing illustrations.

Printing technology in the United States lagged far behind that in England. Although newspapers and periodicals featured pictures of battle scenes during the American Civil War, the quality of the illustrations was poor. Nevertheless, the public’s appetite for artwork had been whetted. In addition, the introduction of public education led to increased literacy, with a subsequent demand for reading material. Where in 1865, some seven hundred periodicals were being published in the United States, by the beginning of the twentieth century, there were over 5,000. The establishment of libraries further increased the market. By the end of the nineteenth century, America had 33 million volumes in 4,000 libraries—more than 2½ times the number of volumes a mere twenty years earlier. Despite this great demand, wood engraving remained the predominant printing method in the United States until the 1880s. Once change came however, it came swiftly. By the end of World War I, America had firmly established itself as a leader in the field of publishing.

During this Victorian era, there was a growing popularity of books for children. Although the first books geared to children were published centuries earlier, these had been limited to cautionary tales and moral lessons. The children’s book as entertainment was born in the 1750s, when John Newbery’s Juvenile Library offered abridged versions of classic tales. As the idea that childhood was a separate state from adulthood and should be “fun” became entrenched in the Victorian era, the demand for toys and books for children grew rapidly.

An interest in stories of exotic places, heroic legends of earlier times, and folk and fairy tales became widespread during the Victorian period, both for children and adults, perhaps as a reaction to the drabness of the Industrial Age.

This great proliferation of illustrated material led to an increased demand for illustrators to supply the art. A surprising number of these illustrators were women—in America alone, some eighty women illustrators are known to have been active during this time.

In many ways, illustration seemed a perfect choice as a career for a woman—a knowledge of drawing, along with music and needlework, was a desirable “feminine” accomplishment, and part of the standard education of the middle- and upper-class woman; moreover, illustration could be practiced at home, without interfering with a woman’s “real” role as wife and mother. However, this rosy view is far from accurate.

The minimal knowledge of art gained as a part of a young lady’s education was not enough to support a career, and educational opportunities in art, as in other fields, were limited for women in the Victorian era. In the mid- to late-nineteenth century, however, several art and design schools specifically for women opened their doors, and still other schools began to admit women. In Great Britain, for example, there was London’s Female School of Design, the Lambeth School of Art and Design, and the Slade School of Art, among others. In the United States, you had the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Drexel Institute of Arts and Sciences in Philadelphia, New York’s Cooper Union Free Art School and Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. And no discussion of illustration in America is complete without mention of Howard Pyle, for no figure is more important to its development, and particularly to the training of female artists. A prolific and talented artist himself, Pyle was also a gifted teacher. Originally on the faculty of Drexel, he opened his own school in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1900. Nearly half of the students in his first class were women, and during the course of his teaching career, he trained sixty female illustrators, including Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green, and Violet Oakley.

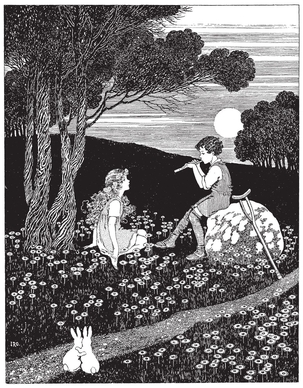

The Little Green Road to Fairyland, 1922

IDA RENTOUL OUTHWAITE

Moreover, the view that a career in illustration was compatible with being a wife and mother was simply not borne out by the facts. In reality, many a talented illustrator, even one who had gained a measure of professional recognition, either gave up her career entirely or drastically curtailed it after marriage. In 1904, Howard Pyle, himself, frustrated after observing this phenomenon, refused to accept any more women students, stating:

The pursuit of art interferes with a girl’s social life and destroys her chances of getting married. Girls are, after all, at best, only qualified for sentimental work.1

Even Jessie Willcox Smith was quoted as saying:

. . . if [a woman] elects to be a housewife and mother—that is her sphere, and no other. Circumstances may, but volition should not, lead her from it.

If on the other hand she elects to go into business or the arts, she must sacrifice motherhood in order to fill successfully her chosen sphere.2

In fact, it was a rare woman indeed who successfully combined family and career, although women who married artists seem to have fared the best, gaining a partner who understood the pressures of deadlines.

What qualities, then, did explain the success of women in the field of illustration? Interestingly, the perception that illustration was an inferior cousin of fine art, worked in their favor—since illustration wasn’t “real” art, it was suitable for “mere” women. According to Frances W. Marshall, assistant editor of St. Nicholas Magazine,

As illustrators, women find themselves in a profession where they stand shoulder to shoulder with their brothers in art. For the publisher, the advertiser, the seller of prints and picture cards is interested only in the finished product, and has no concern whatever as to the sex of the producer.3

She goes on to state:

In this career the natural adaptability of woman is a decided advantage. For an illustrator must be biddable, willing to follow the author’s lead, and subordinate the expression of her own personality to the text which her pictures accompany....

The Now-a-Days Fairy Book, 1911

JESSIE WILLCOX SMITH

. . . [this] does not mean that women must extinguish originality, . . . On the contrary, originality is the trait that most often shortens the road to success. . . Their work demands a certain power of impersonation, the ability to lose one’s self in a character and experience, the emotion the person in the story or the poem is supposed to feel at the moment in which he is represented in the picture.

The rewards for those who stayed the course were substantial. In America, the average illustrator made $4,000 per year, and could earn anywhere from $10,000 up to $75,000. Not surprisingly, women illustrators were most often assigned themes relating to home and children, sentimental tales, romances, and fairy tales. It is unclear whether this was purely a case of stereotyping, or whether many of the women preferred such subjects. Certainly Willcox Smith showed a definite predilection for pictures of children.

Some of the women featured in this book—Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green, Mabel Lucie Attwell, Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, for example—were well-known personalities of their time and had long and illustrious careers. For others, although their name is attached as illustrator of many books spanning a number of years, finding biographical information is extremely difficult. For example, Blanche Fisher Wright, illustrator of The Real Mother Goose, which has never been out of print since its publication in 1916, proved particularly elusive. In part, this difficulty is due to the circumstances mentioned before—the tendency of a female illustrator to cease or interrupt her career upon marriage, thus making her more difficult to trace under her maiden name.

During Great Britain’s “Golden Age of Illustration,” the deluxe gift book, ostensibly for children, lavishly illustrated and elegantly bound, showcased the talents of a number of illustrators. The American Golden Age of Illustration, encompassing the years from the 1880s through the 1930s, includes magazine and advertising illustration as well as book illustration. The 22 artists featured here are but a sampling of the many talented women who participated.