Munich

The first several years we spent in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, we were doing more than just looking at the scant concentrations of trace metals in those distant, pristine waters. At Lake Vanda and the Onyx River, we sank our samplers far into the lake and our cleansed bottles into the river in a search for phosphorus and nitrogen, those elements without which no organism can possibly live. G. Fred Lee had more or less established his reputation on the role that phosphorus plays as a limiting nutrient in lakes and, like myself, he was excited to learn whether or not this same element controlled production in the bizarre waters of Antarctica.

Like many environmental scientists in the early 1960s and ’70s, Fred was becoming aware of the changes that were taking place in some of the once pellucid waters around the world. They were becoming infested with massive algal blooms that at the end of their life cycles died and decayed and rotted, and in the process depleted oxygen—often to near-zero levels—from the water. Fish kills, a loss of clarity, and the unforgettable foul stench of rotten eggs from the sulfides were the results. Limnologists called this process eutrophication. Eutrophication was on spectacular display in the near-shore waters of Lake Erie, and environmentalists predicted that the lake would soon become a dead zone, incapable of supporting life.

What was causing this? When it came to natural waters, there were hundreds of variables, and without background theory it was difficult to know where to begin. Science as puzzle solving, as Thomas Kuhn said. But fortunately, in this case, there were clues that suggested that one (or more) of the elements essential to life was being discharged to natural waters in far greater abundance than in the past. It wasn’t long before suspicion centered on phosphorus, the backbone element—as Watson and his colleagues had shown at Cambridge—of every DNA molecule on the planet.

It was no secret that human activity was rapidly disturbing the natural phosphorus cycle. Anywhere there was intense agriculture, the phosphorus in fertilizers poured from farm fields into streams and lakes, and to this was added phosphates from detergents and nutrient-laden waters from sewage-treatment plants. It was as though the entire watershed conspired against the lake to shift its phosphorus balance. Limnologists called these human-induced changes “cultural eutrophication,” and they were happening rapidly, not at the largo pace of geologic time but in societal time, the paltry years in which we live our lives.

When I taught about eutrophication, I usually mentioned an experiment carried out at the Canada Center for Inland Waters. In one of the many thousands of nameless lakes that dot northern Ontario, scientists divided a single lake in half with a semipermeable membrane. Into one side of the lake they introduced a soluble phosphorus compound. Into the other side, nothing. Then they waited. It wasn’t long before the phosphorous-treated lobe began to turn green, lush as a golf course. It was as though a great feast had been laid before the algae, and they glutted themselves as never before. But beyond the barrier, it was life as usual. The only difference between the two sides of the experimental lake was phosphorus—one side rich, the other poor, poor as it must have been for hundreds of years.

Later, in Dallas, G. Fred Lee and his PhD students Walter Rast and Anne Jones were busy collecting all of the data published in journals and reports on phosphorus inputs to lakes. Following a novel and highly regarded model developed by Richard Vollenweider, G. Fred and his young colleagues looked at the connection between phosphorous pouring in from the watershed and a lake’s clarity, its algal content, and even the quantity of fish the lake could support. What they learned was that there was a clear correlation between phosphorus loading and water quality. Dump in lots of phosphorus and a lake becomes murky. With sparse amounts of phosphorus entering from the watershed, it was just the opposite. The waters were clear and sparkling, as though they had come from a spring. This condition was called oligotrophy, and, aesthetically, it was much to be desired. The famous oligotropic lakes, like Superior and Tahoe, were treasured for their beauty, and they lay far to one side of Fred’s graph. There were others, like Erie, that lay to the other side. When we completed our study of Acton Lake and placed it on the Vollenweider graph, we found that it was much closer to Lake Erie. And the cause was easy to discern: phosphorus poured in springtime from the surrounding farm fields so that the loading—relative to the area and depth of the lake—was high. My hand became a shadow inches beneath the surface.

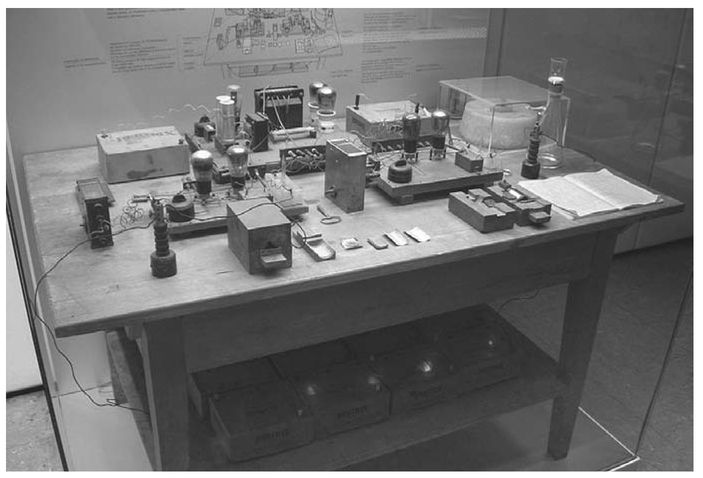

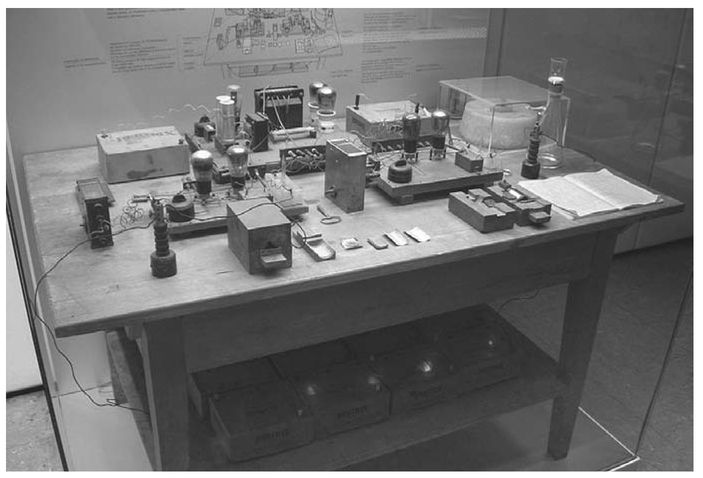

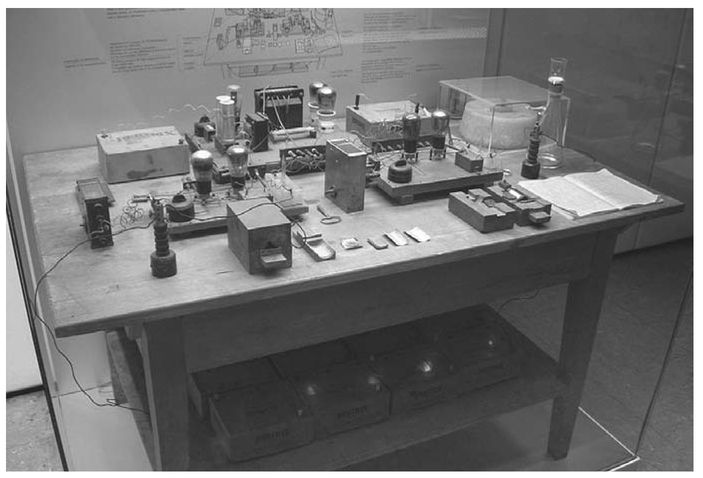

Reconstruction of the fission table at the Deutsche Museum in Munich, Germany

To all of this there was a Boltzmannesque theme: nature’s power to disperse, to scatter and dismiss, to allow nothing to stay long where you had put it. Fertilizers were made from rocks or from the atmosphere, liberally applied to a field in planting time. And yet it was vain hope to think they would remain there, entering the corn stalks to make them taller. The rains would come and the nutrients would be carried off in a great flood. And the phosphorus and nitrogen would advect into the currents and be swept to the lake and then into other currents in the endless junctures of waterways knitting across the continent and into the sea. And there, in far too many places, in depths shallow and deep, dead zones—lifeless of fish and the sediment-dwelling demersals—were forming in ways that were never intended, never predicted, and, like the bottle of blue gas in the front of the classroom, were forever gone from their containers.

The day I arrived in Munich the rains had stopped, but the River Isar was swollen and nearly overflowing its banks. The rivers were special to me, not so much because I studied them in Antarctica and elsewhere, but because they had a kind of historical permanence to them. After his fame had been well established, the great chemist Justus von Liebig accepted a professorship at the University of Munich, more or less the capital city of southern Germany. He would have known the Isar and its floods and would have probably stood on bridges pondering the roiling water pouring from the snowfields of the Alps.

Liebig is known today for his many contributions to chemistry, but high on the list is his “law of the minimum.” This terse statement, of such great importance in ecology, says that a plant will grow in quantity determined by the availability of the element presented to it in least quantity relative to its needs. In lakes in this part of the world, that element was usually phosphorus. It was phosphorus that tended to limit algal production. Not that the soils over which streams flow have little phosphorus in them. Phosphorus is the eleventh most abundant element in the crust. But such is its chemistry that it forms highly insoluble compounds, and these are hardly disturbed by the passage of water. No dissolution. No coaxing into solution. Only a kind of obduracy in the face of water’s challenge, its legendary ability to dissolve all that it touches. So in the past, the quantity of algae was kept in check by the grip of phosphorus minerals, which in their miserly way dispensed of their phosphorus atom by atom, never in displays of magnanimity.

Then it changed. Then we learned to cast phosphorus in more soluble forms, to cast it into detergents and fertilizers and waste products, which in time dispersed and wended their way toward lakes and oceans—all of this neatly captured in the nets of number by Vollenweider and then by G. Fred Lee and Walter Rast and Anne Jones in their global survey.

At Lake Vanda, things worked out much as we knew they would. No one had ever occupied the Wright Valley. Phosphorous came from the rocks and soils, so our measurements of the Onyx River were difficult, so small were the concentrations of that element. When we drilled through the lake ice and sank a Secchi disk through the water column, we could see it swaying on the line from side to side like a tiny pendulum. We lost sight of it at twenty-two meters. The water was that clear. We put the phosphorus loading number and the Secchi disk reading on the Vollenweider graph. The point fell high and to the left, higher than Lake Tahoe. If it hadn’t been for the four-meter ice cover, we could have seen it at an even deeper depth.

And then we realized we were looking far back at what all lakes must have once been.

In the Hofbrauhaus, I was hungry and warm and back into the rhythms of travel and glad to be inside and taking notes on what I had seen that day. A woman and her friends sat beside me on a long bench, and one of them asked, Are these your German reflections?” and I had a pleasant conversation with her about Munich and the differences between northern and southern Germany. She asked when I was returning to London and I told her I was an American and would be leaving Munich in another day for Bremen and then Paris and the States.

That evening, my “German reflections” included more thoughts about Justus von Liebig and how the law of the minimum applied equally to the land, to the growth of crops, and to the fecundity of the very fields that encircled the towns of West Lafayette and Oxford. The required nutrient that disappeared first from the soils was nitrogen, not phosphorus. We are of course living at the bottom of a sea of nitrogen, which makes up 78 percent of our atmosphere. Nitrogen, which serves as a kind of diluent for the explosively reactive gas, oxygen, is for all practical purposes an inert gas. The diatomic molecule, with its atoms linked together by three strong electron bonds—a triple bond—has been nearly impossible to coax into reaction at normal temperatures. Only the nitrogen-fixing bacteria, the soil’s clever chemists, have found a way to do it. Much of German research in the late nineteenth century centered on how to produce synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. It took the long, tedious laboratory studies of Fritz Haber and the engineering skills of Carl Bosch to perfect the reaction between nitrogen and hydrogen required to synthesize ammonia from nitrate so fertilizers could be formed. The geochemist Robert Garrels estimated that the nitrogen taken from the atmosphere by the Haber-Bosch process now equals the nitrogen removed by all of the nitrogen-fixing bacteria on the planet. The long shadow of Justus von Liebig falls across the Earth, from the ten-foot corn in which we lose ourselves in August, as in a maze, to the ice-covered lakes of Antarctica.

There is another, less direct association between Liebig and what we know about the molecular underpinnings of things. Liebig served as mentor to the great organic chemist August Kekulé. We know Kekulé as the man who dreamed the structure of benzene, depending on the version of the story, as a snake catching its tale in its mouth or merely as a whirling presence which became a cycle. Kekulé, whose musings solved the problem of joining six carbons and six hydrogens. Liebig, long before this, saw the brilliance of his young student and convinced him to study chemistry rather than architecture—a subject on which Kekulé had first set his sights. Today we think of Kekulé as the founder of structural chemistry.

The world of molecules, that invisible place below our seeing, is not two-dimensional. It is not simply the composition of a substance written on paper—one of these, four of those, six of something else. Rather, in the wake of Liebig’s brilliant student, it is an architecture of forms, a universe of agitation, as Boltzmann had known, a submicron dance of immense complexity, where there is a link between structure and function. The tetrahedral CFC cannot cling to one of its chlorines in the rain of photons that strike it, and so it departs and engages the triangular ozone, and a series of reactions begins. The cocktail of drugs that flow in the veins counter the errant cancer cells, their complex architecture designed to kill.

Liebig lived between 1803 and 1873, and in his lifetime he saw the full efflorescence of organic chemistry and the work of his many students and what he had set in motion, both in Giessen and here in Munich, with its streams swollen and the beer in the Hofbrauhaus flowing as it always had.

When she was asked to join the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bomb, physicist Lise Meitner declined. She wanted nothing to do with bomb making. Yet she was the first to understand what the results that she and Otto Hahn were getting back in the thirties actually meant. The apparatus they used was on display at the Deutsches Museum in Munich. It had been greatly compressed from the original, whose components occupied three rooms. The version I was staring at was on a small table. It consisted of tube and wires and glassware; as humble as a child’s toy.

Otto Hahn was a genius with his hands and with his analytical skills. In the apparatus before me, only traces of elements were used, only traces formed. They were nearly counting atoms, one by one, as though they were small invisible gems, bits of diamond in the eye of a scope. But they were infinitely smaller, they gave no hint of their being. The critical experiment involved shooting slow neutrons at a uranium target. There was a Baconian aspect to this, A let’s see what happens if we do x. As it turned out, strange results occurred. From what was essentially Meitner’s apparatus, Hahn and Strassman detected the element barium. This seemed odd, a kind of Kuhnian anomaly based on what had been expected. The expectation was that larger elements, that is, elements with greater atomic mass, transuranics, would be produced. But barium has a relative atomic weight of only 137, compared with 235 for the lighter of the uranium isotopes. Hahn was shocked by the presence of barium in the products. These findings were made in Berlin in 1938, by which time Meitner, who was a Jew, had fled to the safety of Stockholm.

Although Hahn and Strassman reported their results in a paper to Naturwissenschaften, they were unable to explain them. It was not until 1939 that Meitner and Otto Frisch communicated their interpretation in a letter to Nature. They were the first to realize that a fission reaction had taken place, that the nucleus had been split. It was not long before the significance of this reaction became known: the release of vast stores of energy; the production of neutrons, which would sustain a chain reaction; the potential for a bomb. It was Albert Einstein, in a letter to Roosevelt, who made these frightening prospects known.

I had never heard of Meitner as an undergraduate, never heard of her in Indiana or Virginia. Even the display at the museum until recently referred to the “work table of Otto Hahn.” There was no mention of Lise Meitner, its principal designer. In the Deutsche Museum this has finally been changed. Meitner is now included as an equal partner.

There is an element at the very end of the periodic table, where few tend to venture, below iridium, which comes to us from space, the death-dust of dinosaurs, the beginning of our own humble ascendancy, in that column of the table in which reside rhodium and cobalt. The symbol for element 109: Mt. It is meitnerium.

The walls of the bar in Bayerstrasse are filled with boxing memorabilia: a robe from Ali’s training camp; gloves from George Foreman; an announcement of the Lewis–Schmeling fight, Yankee Stadium, June 22, 1938; the Ali–Frazier fight, Tuesday, September 30, 1975. It is all mixed together: Munich, Schmeling, Hitler, quantum physics, Einstein, Meitner, the bomb. There is an old Coke ad with a girl in a white sweater and a pink bow in her hair, the red of the Coke dispenser, just as I remember it being when, as kids, we were trying to figure how the earth moved. Over in the corner, an old Wurlitzer, its air bubbles moving in arcs along the lemony plastic, like the place in Pittsburgh where we went to dance. Pictures of Monroe, Bogart, the young Dustin Hoffman. A cigar-store Indian stands just inside the door. There is an old-fashioned telephone booth. It is red, with the word TELEPHONE painted on it.

I am smelling baked chicken, fries, cigar smoke, and the odd draft of spring air from the streets of Munich. A thin girl in jeans and glasses drinks a Coke; her boyfriend in denim drinks a beer. They are smoking Marlboros. Do I remember the blackouts over Pittsburgh during the war, or only stories about them? One night Jack Green, my dad’s brother, a guy who looked like Brando and died young, pointed out the warships plying the Ohio. He said they had been made at Dravo. It was night and I could just see their lights moving on the dark water. A few years later, I collected war cards. Pictures of Mark Clark, Patton, MacArthur, and my favorite, the Finnish resistance fighters on skis, all in white and carrying riffles. In my parents’ dining room, there was the dreamy music of the fifties, before rock and roll: “Harbor Lights,” “Goodnight Irene,” and anything by Rosemary Clooney.

The kids hated Kuhn. Why? He was right; in science, the revolutions are invisible. There were no parades for the double helix, no flags for Meitner, no upheavals or barricades for Einstein when he reimagined light, or for Rutherford and Bohr when they hollowed out the world. For Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, did the crowds cheer and cheer without surcease, did they strike up a band for Edwin Hubble as he came down from Mount Wilson, or for Lavoisier when he told us, finally, how things burned? In the beginning it all looks ramshackle and crazy, like Drake’s well in that field by Oil Creek, or like Boltzmann statistics. For fifty years, Alfred Wegener, who saw that the continents really did move, looked like a nut. Most of all to geologists.

Another Kuhnian truth: Science is inherently conservative. Sometimes you just have to pound and pound, like a prize fighter. Here’s the ring, here are some gloves. Go at it.

Maybe Meitner saw into the future, beyond Hiroshima and Nagasaki to Ike at Shippensport throwing the switch to the first nuclear power plant. Maybe she saw how medicine would one day use our understanding of the nucleus, or how geology would. There were more than bombs. We still have no idea where this will take us.

In a journey, a lifetime is lived. I did not want to leave Munich.