Caernarfon Castle, Constantinople in the West

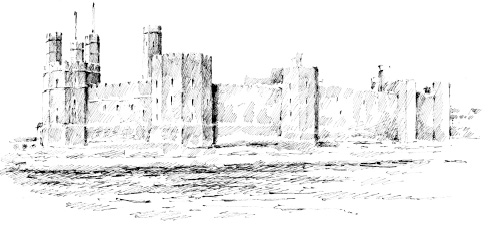

CAERNARFON CASTLE IS the largest of Edward I’s castles in Wales. It was designed to be not just a fortress but also a palace, and a seat of government as well. Begun in 1283, the castle took 50 years to build and, even then, was never finished.

The first impression of Caernarfon Castle is the sheer size of it. The entrance arches soar higher than a cathedral and the tall, grim walls darken the narrow streets below. Voices and footsteps echo in the shadows. You feel cold, cowed, conquered. If Caernarfon Castle has that effect now, then how much more awe and fear did it inspire 1,000 years ago?

But there is more to Caernarfon than simple brute power. There is subtle imagery at work here too. Edward built Caernarfon near the site of the Roman fort of Segontium, the remains of which can still be seen outside the town walls to the south. In AD 383, the commander of the Roman forces in Britain, Magnus Maximus, who was married to the daughter of a Welsh prince, declared himself ‘Caesar’ and went out from Segontium accompanied by many Welsh warriors, to set himself up as Emperor of the West. Although Maximus was eventually defeated, the symbolism of Welsh princes fighting alongside Roman legions was not lost on Edward, and Caernarfon was designed to draw on that symbolism, showing Edward to be the natural successor of Roman imperial power. Each of the three mini turrets of Caernarfon’s distinctive Eagle Tower bears a sculpture of a Roman eagle from Segontium.

The imagery goes deeper still. A strong element in Welsh legend is the belief that the Emperor Constantine (306–37) was born at Segontium, and the banded walls of Caernarfon Castle, lined with strips of dark sandstone and layers of decorative tiles, are deliberately reminiscent of the massive walls of Constantine’s great city in the East, Constantinople, asserting Caernarfon as the Constantinople of the West. A masterpiece, not just of engineering, but of political propaganda.

Edward I even went so far as to make sure that his son, the future Edward II, was born at Caernarfon, in 1284, and was later proclaimed Prince of Wales, thus completing the illusion.

And it worked. Over 700 years later it is accepted almost without question that the eldest son of the reigning monarch should become Prince of Wales. In 1911, the 20th Prince of Wales, another Edward, assumed the title at Caernarfon, and the whole world watched on television as Prince Charles, eldest son of Elizabeth II, was invested as the 21st Prince of Wales in 1969.

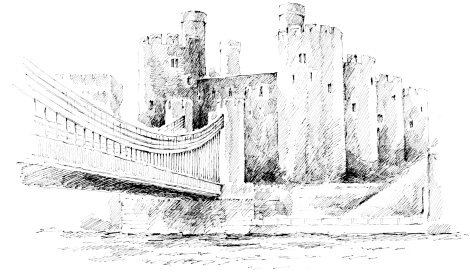

CONWY IS THE MOST COMPLETE MEDIEVAL WALLED TOWN IN BRITAIN. Seen from the river with the mountains as a backdrop, the fantastic castle looms over the bustling rooftops of the town like a crouched lioness guarding her cubs. The castle was begun in 1283, the same year as Caernarfon, but unlike Caernarfon, it was finished in just four years. It is a real ‘Boy’s Own’ castle, rugged and dour, a solid doorman relying on brute muscle to intimidate. And yet, while there is strength outwardly, there is also beauty within – the Chapel Royal inside the Chapel Tower is quite lovely

Three bridges lead across the river to the castle at the gate. The 1958 road bridge is ugly. Obviously no thought was given to how it might be made to enhance rather than ruin the view. Its chief misdemeanour is to hide Thomas Telford’s graceful suspension bridge, built in 1822, with turreted piers at each end in deference to the great towers of the castle. This bridge was a mini prototype of Telford’s 1826 Menai Bridge, 20 miles (32 km) to the west, and therefore not just beautiful to look at but of great historical significance. In 1965 the town council voted to demolish it, but thankfully the National Trust stepped in to save it, and you can now walk across it forever, on payment of a small toll at the restored toll house.

Next to it runs Robert Stephenson’s Tubular Railway Bridge of 1847, also a prototype for his Britannia Tubular Railway Bridge of 1850, across the Menai Strait. The Conwy bridge provides us with a good opportunity today to see what the Britannia Bridge looked like before the fire of 1970. At Conwy, trains still disappear into the tubes and re-emerge the other end like snakes from a hole. Stephenson, like Telford, made an effort to have his bridge blend in, by raising crenellated towers at each end.

All three bridges decant their traffic at the narrow town gate, and Conwy used to be a real bottleneck, but now cars are taken under the town in a tunnel, THE FIRST IMMERSED TUBE TUNNEL IN BRITAIN.

It is possible to walk virtually all the way around Conwy along the town walls. They are three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) in length, include three gates and 21 towers, and were built as an integral part of the defences at the same time as the castle. Enclosed within the walls is a virtually unchanged medieval townscape of almost film set quality.

ABERCONWY HOUSE in Castle Street, a timber and stone merchant’s dwelling now run by the National Trust, dates from the 14th century and is THE OLDEST TOWN HOUSE IN WALES.

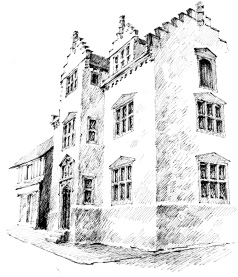

In the High Street is THE FINEST TOWN HOUSE IN WALES, PLAS MAWR, an Elizabethan mansion built around an inner courtyard, with a decorated stone facade and more than 50 mullioned windows. It was built for Robert Wynne, a rich merchant, in 1576, taken over by the Mostyns, and then given to the nation in 1991.

In sharp contrast, down on the quay is THE SMALLEST HOUSE IN BRITAIN, just 10 ft 2 inches (3.1 m) high and 6 ft (1.8 m) wide. It has only two rooms, and the last tenant was a fisherman who was 6 ft 3 inches (1.9 m) tall.

BANGOR CAME INTO existence around AD 525, when a monk by the name of ST DEINIOL established a cell on the site, building a church and enclosing the small community with a type of wattle fence known as a ‘bangor’. In AD 546, St Deiniol was officially granted the land by Maelgwn, King of Gwynedd, and the church became BRITAIN’S SECOND CATHEDRAL, after Whithorn in Scotland. The land around became THE FIRST TERRITORIAL DIOCESE IN BRITAIN, with St Deiniol as its first Bishop. Bangor is now THE OLDEST CATHEDRAL STILL IN USE IN BRITAIN.

The first stone cathedral was begun by Bishop David in 1120, but destroyed by King John in 1210. The present building dates largely from the 13th century, and underwent a major restoration by Sir George Gilbert Scott, in the 1870s.

The grandfather of Llywelyn the Great, Owain Gwynedd, Prince of Gwynedd, who died in 1170, was buried at the High Altar of the Norman church, near where the Bishop’s throne now stands.

Next to the former Bishop’s Palace, now council offices, is a BIBLE GARDEN planted in 1962 by Tatham Whitehead, with every type of plant and tree mentioned in the Bible, or, at least, all those able to survive the Welsh climate. There are examples of the Fig Tree from the Garden of Eden, the Judas Tree on which Judas Iscariot hanged himself, and the Glastonbury Thorn, grown from the staff of Joseph of Arimathea.

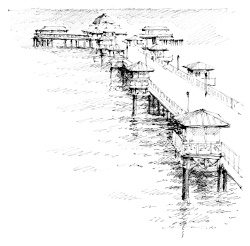

For hundreds of years Bangor was no more than a village, and the old settlement gathered around the modest cathedral on the side of a valley still has the air of a small country town. In 1884, the University College of North Wales was founded across the valley, overlooking the Cathedral. Earlier in the 19th century, docks were built to cater for the booming slate industry and Bangor suddenly took on a commercial role, as well as becoming an important resort, with the introduction of the steam packet from Liverpool. In 1896, a pier was built, reaching 1,500 ft (457 m) out into the Menai Strait, THE SECOND LONGEST PIER IN WALES. The view from the end of the pier, which was restored in the 1980s, is tremendous, taking in the mountains, the boats passing through the strait, and the handsome houses of Anglesey with their gardens running down to the water’s edge.

All this raucous activity, however, does not impinge one bit on the cloistered peace of the university and cathedral quarter, tucked away in its valley behind Bangor mountain. They seem like two completely different towns and it is this dichotomy that gives Bangor its special flavour.

In 1967, THE BEATLES came to stay in one of the university halls of residence, Neuadd Reichel, to meet Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and it was while they were here that they learned of the suicide of their manager Brian Epstein.

ON THE OUTSKIRTS of Bangor, to the south-west, a 7-mile (11 km) long wall hides what was, until recently, the mysterious world of VAYNOL PARK. In 2005, the National Eisteddfod was held here, and every August Bank Holiday since the year 2000, Vaynol has been the home of Bangor-born BRYN TERFEL’S Faenol Festival which brings together top names from the world of opera, musicals and Welsh pop music, for a three-day open-air concert.

Before that, very little was known of what was behind the wall. To begin with, there are two Vaynol Halls: the rather unimaginative early 19th-century Vaynol New Hall, now a conference centre, and the utterly gorgeous but dilapidated Elizabethan Old Hall, one of the finest Tudor houses in Wales, which was featured on BBC2’s first Restoration series.

The last private owner of the estate was Sir Michael Duff, 3rd Bt, who died in 1980. He and his wife Lady Caroline led rather colourful lives. Sir Michael was godfather to Princess Margaret’s husband, Lord Snowdon, and Lady Caroline was the daughter of the 6th Marquess of Anglesey, from Plas Newydd. Amongst her very, very close friends were Prime Minister Anthony Eden and the artist Rex Whistler, whose murals of Snowdonia and the Menai Strait, as seen from Vaynol Park, can be seen today at Plas Newydd.

So hidden away and secret was Vaynol that politicians, society types, and Royalty could all come here and disappear without anyone knowing they were there. The Queen Mother, the Queen, Princess Margaret, Harold Macmillan and his family, all were able to let their hair down in complete confidence at Vaynol. Some 18 members of the Royal Family gathered there for the investiture of Prince Charles at Caernarfon in 1969.

Today much of the estate is open to the public. There are two viewing platforms by the sea and a folly built to rival the Marquess of Anglesey’s Column across the Menai Strait.

PENRHYN CASTLE, ON the eastern outskirts of Bangor, was built for the Pennant family on profits from West Indian sugar and, as with Vaynol New Hall on the other side of Bangor, Welsh slate. Built by Thomas Hopper between 1820 and 1845, it is a monstrous place, fashioned like a Norman castle, the five-storey main tower a copy of the keep at Castle Hedingham in Essex. Inside, the castle, now owned by the National Trust, seems to go on for miles, with corridors and stairways and state rooms filled with Rembrandts, Canalettos and Gainsboroughs and heavy oak furniture. The Great Hall is simply cavernous, and the opulent Grand Staircase took ten years to build. One of the highlights is a huge four-poster bed made of slate, weighing over one ton and commissioned for the visit of Queen Victoria in 1859 – she apparently refused to sleep in it.

The extensive grounds include a Victorian walled garden and afford stupendous views out across the Menai Strait, north towards the Great Orme and south and west to the mountains.

Source of all this wealth, the Penrhyn Quarry at BETHESDA, 5 miles (8 km) inland to the south, is THE BIGGEST SLATE QUARRY IN THE WORLD, some 1,200 ft (366 m) deep, and still being worked today. In 1801, THE FIRST NARROW-GAUGE, HORSE-DRAWN RAILWAY IN WALES was laid between the quarry and Port Penrhyn at Bangor. The line closed in 1962, but two of the steam engines that were introduced in 1878 are now at work on the Ffestiniog Railway (see Merioneth).

Slate from here has been used for floors, roof tiles, furniture and headstones, not just in Wales but all over the world. As well as the unmistakable flat galleries carved out of the sides of the mountains, and the slag-heaps and vast, shining, grey slopes of broken slate, there are some intriguing monuments still to be seen of the Victorian heyday of the slate industry. Preserved at Penrhyn Quarry is a huge water balance incline, where platforms with water tanks underneath were used to haul slate out of the quarry by filling and emptying the tanks – the weight of an empty wagon with a full tank of water being sufficient to haul up a loaded wagon with an empty tank. Down at Port Penrhyn there is an original locomotive shed and a neat little circular lavatory.

Most of the Pennant family are buried in St Tegai’s church in Llandygai, the estate village at the gates of Penrhyn Castle. A notable exception is Lord George Sholto Gordon Douglas-Pennant, 2nd Baron Penrhyn of Llandegai (1836–1907). He was a fierce opponent of the trade unions and ran the quarry like a feudal lord of old. This led to friction with his quarrymen, and a three-year lock-out lasting from 1900 to 1903, THE LONGEST INDUSTRIAL DISPUTE IN BRITISH HISTORY.

LLANDUDNO IS THE LARGEST SEASIDE RESORT IN WALES. Developed in the 1850s, it is elegant, Victorian and wonderfully unspoilt, and has the benefit of two fine beaches, the North Shore and the West Shore.

On the North Shore, grand white, pink and blue hotels overlook the Promenade, which follows the softly curving bay for 2 miles (3.2 km) between high headlands, the Great Orme and the Little Orme. Here is Sir John Betjeman’s favourite pier, opened in 1878, at 2,295 ft (700 m) THE LONGEST PIER IN WALES, acres of iron lacework floating on the sea like a Byzantine palace.

Across the narrow neck of the Great Orme is the West Shore, miles of quiet sand at the mouth of the River Conwy, with fine views towards Conwy and Anglesey. In 1933 Lloyd George came here to unveil a statue of the White Rabbit from Alice in Wonderland, commemorating the many happy summer holidays that Alice Liddell, the model for Alice, spent here with her parents in the 1860s. At first they stayed at what is now the St Tudno Hotel, and then at Penmorfa, the house that Alice’s father, the Very Revd Dr Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, had built for them as a holiday home. Whether the author of Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, actually visited Alice here is unproven, but looking out from Penmorfa across the wide expanse of sand, it is easy to imagine that it was here that the Walrus and the Carpenter ‘wept like anything to see such quantities of sand …’ Penmorfa, much extended, is now a hotel.

Between the North and West Shores, encompassed by the 5-mile (8 km) Marine Drive, is the GREAT ORME, Orme being a Norse word for sea ogre. This particular sea ogre, 679 ft (207 m) high, 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and 2 miles (3.2 km) long, is packed with superlatives, old and new. To start with, the view from the top is superlative, as are the many archaeological treasures to be found all over the headland. There is a neolithic burial chamber, an Iron Age fort, a medieval village, the Great Orme Long Huts and, most exciting of all, the GREAT ORME BRONZE AGE COPPER MINE, discovered in 1987 and THE ONLY BRONZE AGE COPPER MINE IN THE WORLD OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.

There are myriad ways to get to the top of the Great Orme. One way is to take the ornate GREAT ORME TRAMWAY, engineered in 1902, THE ONLY CABLE-HAULED STREET TRAMWAY IN BRITAIN and one of only three surviving in the world, the others being in Lisbon and San Francisco.

Another way to the summit is via BRITAIN’S SECOND LONGEST CABLE CAR, the LLANDUDNO CABIN LIFT, completed in 1972 and just over 1 mile (1.6 km) long.

The cabin lift’s lower station is situated on the eastern side of the Great Orme in a sheltered valley known as Happy Valley, given to Llandudno in 1887 by the 3rd Lord Mostyn, the local landowner, in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The Mostyn family are THE OLDEST LANDOWNING FAMILY IN WALES AFTER THE CROWN. There is a restored Victorian camera obscura of 1860 here, and a little higher up, THE LONGEST ARTIFICIAL SKI SLOPE IN BRITAIN, nearly 1,000 ft (300 m) long, built in 1987.

If you decide to climb to the top of the Great Orme on foot, look out for the wild goats, descendants of a pair given to Queen Victoria by the Shah of Persia, and donated to the Great Orme by Lord Mostyn.

Llandudno’s lifeboat station is THE ONLY INSHORE LIFEBOAT STATION IN BRITAIN. It sits on the neck of the Great Orme, halfway between the North Shore and the West Shore, so that the lifeboats can be swiftly launched from their trailers off either shore.

THE LLEYN PENINSULA recedes far out into the Irish sea mists, poised above the tear drop that is Bardsey Island, like a hand reaching out for a sweet. It is the most remote, secluded and mysterious part of Wales, more so even than Anglesey, for it is far less visited, was never fought over, and has no gold or copper or palaces to be won. What it does have is a desolate beauty, secret landscapes and simple monuments to the many pilgrims who trod the ancient route from Caernarfon to Aberdaron, and thence to Bardsey, Wales’s most holy island.

First stop along the north coast road from Caernarfon is the shrine of ST BUENO, considered to be the patron saint of North Wales. The 15th-century church here is huge and lavish, built with money from pilgrims on their way to Bardsey, and built on to the little chapel that covers the site of St Bueno’s shrine. Pilgrims who slept here overnight would be cured of their epilepsy and rickets by drinking from the nearby St Bueno’s Well next morning. In the churchyard is ONE OF ONLY TWO CELTIC SUNDIALS IN BRITAIN.

St Bueno’s

The north coast of Lleyn is a bleak moonscape with few breaks in the cliffs. Visible for miles around is a mountain with three sharp peaks known as Yr Eifl, or the ‘Fork’, highest point on the Lleyn Peninsula. On the southern slope stands one of the great Iron Age forts of Wales, TRE’R CEIRI, ‘town of the giants’. It was still lived in during Roman times and at 1,500 ft (457 m) up, is almost impossible to get to. This may explain why it is so well preserved, with evidence of some 150 huts and complete sections of high wall up to 15 ft (4.6 m) thick. If you can make the stiff climb the view is stupendous, with sea all around and, far, far below, the deep, dark valley of Nant Gwrtheyrn.

NANT GWRTHEYRN is named after the 5th-century Celtic King Vortigern, who died here, maddened and alone after being dispossessed of his kingdom by the very Saxons he had invited in to protect him. There is a melancholy here that speaks of some tragedy, and maybe gives credence to the legend that Nant Gwrtheyrn was cursed, after the inhabitants of the little fishing community here refused hospitality to some monks travelling to Bardsey.

The small harbour, built to ship slate from the surrounding hills, was abandoned for a while after the quarries closed, but now the settlement has been developed as a residential centre for learning the Welsh language. It can be reached by the steepest road I have ever driven, which snakes down through a brooding wood of dripping trees, before opening out on to two small sunlit rows of cottages, whose windows gaze across the sea to Celtic Ireland.

Westwards, at PISTYLL, sited below the road and sheltered by trees, is another St Bueno’s Church built by pilgrims, 12th-century this time, also with a healing well. If you turn right inside the church gate and walk along the pathway, you will come to a low headstone almost hidden in the grass. This is the last resting-place of actor RUPERT DAVIES (1916–76), voted TV Actor of the Year in 1963 for his portrayal of pipe-smoking detective Maigret. On meeting Davies for the first time, Georges Simenon, Maigret’s creator, exclaimed, ‘At last, I have found the perfect Maigret!’ For slightly younger viewers, Rupert Davies was the voice of Professor Ian McClaine (Mac) in the Joe 90 puppet series. Pistyll was his holiday retreat.

Overlooked by the Iron Age hill fort of Garn Fadryn, midway between Nefyn and Abersoch, is a sturdy gatehouse that once guarded the entrance to the romantic 16th-century MADRYN CASTLE. The castle is no more, demolished in 1910, its contents dispersed, its foundations now hard core for a caravan site. The name of Madryn did not die, however, for over on the other side of the world, on the coast of Patagonia, there is the town of Puerto Madryn. The owner of Madryn Castle, SIR THOMAS DUNCOMBE LOVE JONES-PARRY BT (1832–91) sailed to South America in 1862, accompanied by Caernarfon-born Lewis Jones, to investigate the feasibility of setting up a Welsh settlement there (see Bala, Merioneth). They named the bay where they first made landfall Porth Madryn, after Love Jones-Parry’s ancestral home.

Rupert Davies

One of the few beaches on the rocky north coast of the Lleyn Peninsula is at PORTH OER, about 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Aberdaron. The cove is also known in English as Whistling Sands – at certain stages of the tide, the smooth white sand actually whistles or squeaks as you walk across it. The noise is caused by the unusually shaped grains rubbing together as they are compressed.

SEEN FROM THE 534 ft (162 m) high summit of Mynydd Mawr on the tip of Lleyn, against a backdrop of the great arc of Cardigan Bay, BARDSEY ISLAND looks deceptively small, and the waters between, calm and placid. The distinctive shape seems hunched up, its back turned against the mainland in disdain, the great 550 ft (168 m) high bulk of Mynydd Enlii concealing any view of the island’s settlement, compounding the illusion. But this is one of the great holy sites of the Celtic world, the Iona of Wales.

A monastery was founded on Bardsey in AD 516 by St Cadfan, although long before that the island had been used as a sanctuary for Christians escaping the terrors of post-Roman Britain. The Welsh name for Bardsey, Ynys Enlli, means ‘island of currents’, and the treacherous waters of the Sound made the journey extremely perilous – three pilgrimages to Bardsey was considered the equal of one to Rome. Chapels and churches were set up on the mainland, where pilgrims could pray for safe passage across. Many came to die and be buried on Bardsey, and another name for the island is ‘island of 20,000 saints’.

Although St Cadfan’s monastery remained as one of the last bastions of Celtic Christianity for several hundred years, there is very little evidence left of it or of the 13th-century Augustinian abbey that replaced it. Part of a tower, some walls and plenty of Celtic crosses stand testament.

In the 19th century Bardsey was part of the Newborough estates and supported a population of some 100 crofters and fishermen and their families. Only one of the original crofts, Carreg Bach, is still there, the rest of the community having been rebuilt in the 1870s, with the chapel of 1875 the last building to be put up.

Today Bardsey is owned by the Bardsey Island Trust and it is possible to stay on the island in one of the farmhouses or cottages. Boat trips leave from Aberdaron and Pwllheli.

Bardsey possesses THE TALLEST SQUARE LIGHTHOUSE IN BRITAIN, 98 ft (30 m) high.

The colloquial term for a lavatory in Welsh, ‘ty bach’ or ‘little house’, came from the ‘ty bach’ in the garden on Bardsey.

An apple tree thought to have been growing in the island since the 14th century is the source of ‘THE WORLD’S RAREST APPLE’, the BARDSEY ISLAND APPLE. It was originally unique to Bardsey, but it is now possible to buy saplings from the tree.

THE SOUTH COAST of the Lleyn Peninsula is much softer and gentler than the north, with sandy beaches and colourful fishing villages, attracting yachtsmen and holiday-makers.

For many centuries the main embarkation point for Bardsey island was Aberdaron, consisting of a cluster of cottages, an old humpbacked bridge, a medieval resting house, Y Gegin Fawr, meaning ‘the big kitchen’, where you can still eat, and a huge church, almost on the beach and half buried in sand. Originally founded in the 5th century by St Hywyn, the church was greatly enlarged in the early 12th century, and a second nave added in the 15th century, to cope with the growing number of pilgrims. Lots of space inside, but the simple, single Norman doorway is tiny. To sit in the stillness of this lovely church at the far end of the world, where so many have come to pray for courage to face what lies ahead, listening to the waves lapping almost to the door, is a deeply moving experience. The 21st century seems very far away, as indeed it is, for Aberdaron lies FURTHER AWAY FROM A RAILWAY STATION THAN ANYWHERE ELSE IN ENGLAND AND WALES.

Unexpected, and half hidden behind tumbling banks of shrubs and flowers, up on the hill above the turbulent bay that is Hell’s Mouth, sits one of the most romantic little houses in Wales, PLAS YN RHIW. It was rescued from neglect in 1938 by the three Keating sisters, who restored the house and planted a magic garden in the woods with every plant and flower imaginable. A small stone manor house dressed up as a country cottage, Plas yn Rhiw is mainly 16th century with Georgian additions. The views of Cardigan Bay are breathtaking, the polished stone floor in the main hall is the most gorgeous I have ever seen, and the gardens overflow with colour and bowers and secret walkways. It is hard to step back out into the real world.

EVEN THOUGH HE has been dead for more than 50 years, DAVID LLOYD GEORGE (1863–1945) still dominates the village of LLANYSTUMDWY, on the Lleyn Peninsula near Criccieth, as he dominated the world of politics in his lifetime. He was born in Manchester, the son of a Pembrokeshire schoolmaster, but came to live in Llanystumdwy with his uncle, Richard Lloyd, at the age of two, after his father died. HIGHGATE, the stone house he lived in for 15 years, stands opposite the village pub and has been restored to how it was when he was a boy. The comprehensive LLOYD GEORGE MUSEUM tells the story of his life, with the help of personal items such as a lock of his white hair, his pipes and walking sticks and his own copy of the Versailles Peace Treaty. His initials can be seen carved in the stonework of the bridge over the River Dwyfor, at the bottom of the village.

David Lloyd George, THE ONLY WELSH PRIME MINISTER OF GREAT BRITAIN, became an MP in 1890 and represented Caernarfon for 55 years. As Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1908 and 1911 he laid the foundations of the Welfare State, introducing the Old Age Pension and the National Insurance scheme. His ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909 set out to tax the rich in order to help the poor and was blocked by the House of Lords. This resulted in the 1911 Parliament Act, restricting the powers of the Lords. His greatest political ally at the time was Winston Churchill and together they were known as the ‘Heavenly Twins’.

Lloyd George became Prime Minister in 1916 and his policies helped to ensure victory in the First World War, albeit at a terrible price. He was instrumental in negotiating the ill-fated Treaty of Versailles alongside US President Woodrow Wilson and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

During his premiership, the 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote to women over 30, opening the way for women to achieve the same voting rights as men in 1928.

In 1921, Lloyd George forced through the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which saw the creation of the Irish Free State, while excluding the six counties of Ulster that became Northern Ireland.

He had his setbacks. In 1907, the greatest tragedy of his life happened when his beloved elder daughter Mair died at the age of 17. In 1913, his London home was blown up by militant suffragettes. And at the end of his Prime Ministerial career he was accused of corruption, for handing out peerages in return for contributions to party funds. This led to the 1925 Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act.

Lloyd George had two nicknames, ‘the Welsh Wizard’, referring particularly to his skill as a wartime leader and negotiator, and ‘the Goat’, which referred to his reputation as a womaniser.

He is remembered for his brilliant oratory. After watching Lloyd George make a speech to a large crowd, photographer Alvin Coburn observed, ‘He had them under his spell, as a conductor holds his orchestra, and he could do what he pleased with them.’

His trademark was his moustache – he was one of nine British Prime Ministers to sport a moustache. During a trip to Canada in 1899 he shaved it off, and on his return to the House of Commons, the Speaker failed to recognise him. He never shaved it off again.

His personal life was complicated. He had a constituency home in Criccieth called Brynawelon, on a hill overlooking the bay, where his wife Margaret lived. He also had a house in Churt in Surrey, where he lived much of the time with his secretary Frances Stevenson, by whom he had a daughter in 1929. He married Frances in 1943 after the death of his wife, to whom he had remained devoted, in 1941.

In 1944 he retired from politics, and returned home to Llanystumdwy, becoming Earl Lloyd George of Dwyfor and Viscount Gwynedd. He died in March the following year. He had already chosen the place where he wanted to be buried, pacing up and down during a family picnic beside the River Dwyfor until he found exactly the right spot. He then bought the land and had it consecrated.

He chose well. His grave is in a sublime location, under the trees above the River Dwyfor, just upstream from the bridge. His tombstone is the large grey boulder on which he used to sit beside the river and think, set in the middle of a small, oval lawn, reached through an iron gate and surrounded by a low wall of Welsh stone. It was designed by his friend Clough Williams-Ellis (see Merioneth) and is perfect.

Driving through the mountains of Snowdonia on his way to Caernarfon, Lloyd George took the wrong turning and got himself lost. He stopped to ask where he was and was told, ‘You’re in a motor car.’ Long afterwards he referred to this as the perfect kind of answer to a Parliamentary question – ‘it’s true, it’s brief and it tells you absolutely nothing you don’t already know!’

IDYLLIC GWYDIR CASTLE, a remarkable example of a 16th-century Tudor courtyard house, was built for the powerful Wynn family and vies with Plas Teg in Flintshire as THE MOST HAUNTED HOUSE IN WALES. Sir John Wynn (1553–1627) had a reputation as a ruthless tyrant, and was said to have seduced a servant girl and then murdered her and bricked her body up in one of the chimney breasts. Today the stench of her decomposing body can still be experienced in the passageway near the Great Hall. Sir John himself apparently lies under Swallow Falls at Betws-y-Coed, until the water has purified him of his evil deeds.

Gwydir Castle was badly damaged by fire in 1920 and caught the rapacious eye of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst (immortalised by Orson Welles in Citizen Kane), who was touring Britain looking for artefacts to fill his castle at San Simeon in California. He snapped up the Jacobean wood-panelled dining-room from Gwydir and shipped it across the Atlantic, where it remained packed away in boxes. When Hearst died in 1956, the panels were bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum in New York and put into storage. Meanwhile Gwydir gradually became derelict until rescued in 1994 by architect Peter Welford and his wife Judy Corbett, who retired from city life and set about restoring the house. They traced the dining-room to New York – oak fireplace, doorcase, panelling, gold and silver leather frieze – and negotiated to have it returned, the first time any of Hearst’s collection had been repatriated. In 1998, the Prince of Wales officially reopened the dining-room at Gwydir, fully restored to its glorious best.

AT 3,560 FT (1,085 m) high, MT SNOWDON is THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN ENGLAND AND WALES, the tallest of 15 peaks in Wales over 3,000 ft (914 m). The summit Mt Snowdon is THE WETTEST PLACE IN WALES, averaging 180 inches (4,570 mm) of rain every year.

Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man to climb Mt Everest, trained with his team on the slopes of Mt Snowdon before setting off for his triumphant ascent of the world’s highest mountain in 1953.

The SNOWDON MOUNTAIN RAILWAY was built in 1896 and climbs 2,950 ft (900 m) over 5 miles (8 km), from Llanberis to a few yards short of the summit. It is THE ONLY RACK AND PINION RAILWAY IN BRITAIN.

Mt Snowdon is one of the traditional SEVEN WONDERS OF WALES.

T. E. LAWRENCE (1888–1935), better known as Lawrence of Arabia, was born in TREMADOG, at Snowdon Lodge, an undistinguished house on the southern approach to the town, opposite Capel Peniel.

BANGOR has THE LONGEST HIGH STREET IN WALES.

RAF LLANDWROG, now CAERNARFON AIR WORLD, is the home of THE FIRST RAF MOUNTAIN RESCUE SERVICE.

Wales’s most celebrated harpist and composer DAFYDD Y GARREG WEN, who died in 1749 aged 29, is buried in an isolated country churchyard off the road at Pentrefelin near Criccieth, under a tombstone with a harp carved on it. THE VERY FIRST WELSH WORDS EVER HEARD ON THE BBC, in 1923, were sung to a tune that Dafydd composed on his deathbed, called after him ‘Dafydd y Garreg Wen’.

GREENWOOD FOREST PARK, near Bangor, has THE LONGEST SLIDE IN WALES.

ABER FALLS at Abergwyngregyn, near Bangor, is THE LARGEST NATURAL WATERFALL IN WALES.

Set in the beautiful woodlands of the upper Conwy valley some 3 miles (5 km) south of Betws-y-coed, is TY MAWR, birthplace of BISHOP WILLIAM MORGAN (1545–1604) who, in 1588, completed the translation of the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek into Welsh. The 16th-century stone farmhouse is run by the National Trust and contains a comprehensive collection of Bibles in Welsh and other languages.

The NATIONAL SLATE MUSEUM at Llanberis boasts THE LARGEST WORKING WATER-WHEEL IN MAINLAND BRITAIN.

DINORWIG POWER STATION sits nearly half a mile (0.8 m) deep inside Snowdonia’s Elidir Mountain, near Llanberis, inside THE LARGEST MAN-MADE CAVERN IN EUROPE.

SWALLOW FALLS (Rhaeadr Ewynnol) at Betws-y-coed is THE MOST VISITED WATERFALL IN BRITAIN.

Betws-y-coed claims THE UGLIEST HOUSE IN WALES. The UGLY HOUSE is thought to be an example of a ‘One Night House’ (see Pembrokeshire).

The SNOWDONIA NATIONAL PARK is THE LARGEST PARK IN WALES. Opened in 1951, it covers an area of 838 sq. miles (2,170 sq. km).

While he went off hunting, Prince Llywelyn the Great left his dog, GELERT, to guard his baby son. On his return, the Prince found the dog covered in blood and no sign of the child. Enraged, he slew Gelert, only to discover the baby hidden under the bed, safe and sound, and a dead wolf lying nearby. Gelert had, in fact, saved the baby from the wolf. Distraught, Llywelyn buried Gelert in a magnificent grave down by the river, which is still there to this day. In 1802, a local hotel owner embellished this popular legend to attract customers, and the picturesque mountain village of BEDDGELERT (Gelert’s Grave) has flourished ever since.

ALFRED BESTALL (1892–1986), one of the writers and illustrators of Rupert Bear, lived for a while in Beddgelert.

In the churchyard of ST CIAN’S AT LLANGIAN, near Abersoch on the Lleyn Peninsula, there is a stone pillar bearing a Latin inscription that reads, in three vertical lines, ‘Meli Medici Fili Martini Iacit’ – ‘The body of Melus the Doctor, son of Martinus, lies here’. The stone was carved probably in the 5th century, and not only is it THE FIRST MENTION ANYWHERE IN WALES OF A DOCTOR, it is THE ONLY KNOWN RECORD OF A ‘MEDICUS’ ON ANY EARLY CHRISTIAN INSCRIPTION IN BRITAIN.

PLAID CYMRU, the Welsh nationalist party, was founded in PWLLHELI, on 5 August 1925, during the National Eisteddfod. Six members were present, and the immediate aim of the party was to gain recognition for the aspirations of the Welsh people, followed by self rule for Wales. In 1966, GWYNFOR EVANS became the first Plaid Cymru MP, winning the Carmarthen by-election.

THE OLDEST TREE IN WALES is the LLANGERNYW YEW in St Digain’s Churchyard, Llangernyw, near Conwy. It is approximately 4,000 years old.