Chapter 3: Designing Bulletproof Databases

We’ve already looked at one of the most basic assumptions about relational database systems—that is, that data are spread across a number of tables that are related through primary and foreign keys (see Chapter 1 for a review). Although this basic principle is easy to understand, it can be much more difficult to understand why and when data should be broken into separate tables.

Because the data managed by a relational database such as Access exist in a number of different tables, there must be some way to connect the data. The more efficiently the database performs these connections, the better and more flexible the database application as a whole will function.

Although databases are meant to model real-world situations or at least manage the data involved in real-world situations, even the most complex situation is reduced to a number of relationships between pairs of tables. As the data managed by the database become more complex, you may need to add more tables to the design. For instance, a database to manage employee affairs for a company will include tables for employee information (name, Social Security number, address, hire date, and so on), payroll information, benefits programs the employee belongs to, and so on.

When working with the actual data, however, you concentrate on the relationship between two tables at a time. You might create the employees and payroll tables first, connecting these tables with a relationship to make it easy to find all of the payroll information for an employee.

This chapter uses the database named Chapter03.mdb. If you haven’t already copied it onto your machine from the CD, you’ll need to do so now. If you’re following the examples, you can use the tables in this database or create the tables yourself in another database.

In Chapters 1 and 2 you saw examples of common relationships found in many Access databases. By far the most common type of table relationship is the one-to-many. The Access Auto Auction application has many such relationships: Each record in the Contacts table is related to one or more records in the Sales table (each contact may have purchased more than one item through Access Auto Auctions). (We cover one-to-many relationships in detail later in this chapter.) You can easily imagine an arrangement that would permit the data contained in the Contacts and Sales tables to be combined within a single table. All that’s needed is a separate row for each order placed by each of the contacts. As new orders come in, new rows containing the contact and order information are added to the table.

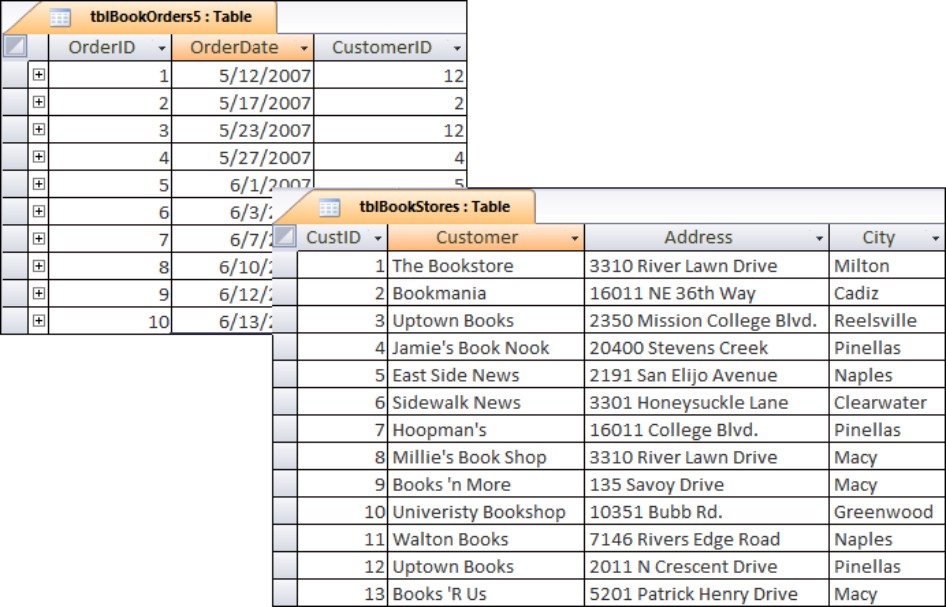

The Access table shown in Figure 3-1 is an example of such an arrangement. In this figure, the OrderID column contains the order number placed by the contact (the data in this table have been sorted by CustomerID to show how many orders have been placed by each contact). The table in Figure 3-1 was created by combining data from the Contacts and Orders tables in the Northwind Traders sample database and is included in the RelationshipsExamples.accdb database file on this book’s CD.

Figure 3-1

An Access table containing contact and orders data

Notice the OrderID column to the right of the CompanyName column. Each contact (like Alfreds Futterkiste) has placed a number of orders. Columns to the far right in this table (beyond the right edge of the figure) contain more information about each contact, including address and phone numbers, while columns beyond the company information contain the specific order information. In all, this table contains 24 different fields.

The design shown in Figure 3-1 is what happens when a spreadsheet application such as Excel is used for database purposes. Because Excel is entirely spreadsheet oriented, there is no provision for breaking up data into separate tables, encouraging users to keep everything in one massive spreadsheet.

Such an arrangement has a couple of problems:

• The table quickly becomes unmanageably large. The Northwind Traders Contacts table contains 11 different fields, while the Orders table contains 14 more. One field—OrderID—overlaps both tables. Each time an order is placed, all 24 data fields in the combined table would be added for each record added to the table.

• Data are difficult to maintain and update. Making simple changes to the data in the large table—for instance, changing a contact’s phone or fax number—would involve searching through all records in the table, changing every occurrence of the phone number. It would be easy to make an erroneous entry or miss one or more instances. The fewer records needing changes, the better off the user will be.

• A monolithic table design is wasteful of disk space and other resources. Because the combined table would contain a huge amount of redundant data (for instance, a contact’s address), a large amount of hard-drive space would be consumed by the redundant information. In addition to wasted disk space, network traffic, computer memory, and other resources would be poorly utilized.

A much better design—the relational design—moves the repeated data into a separate table, leaving a field in the first table to serve as a reference to the data in the second table. The additional field required by the relational model is a small price to pay for the efficiencies gained by moving redundant data out of the table.

Data Normalization

The process of splitting data across multiple tables is called normalizing the data. There are several stages of normalization; the first through the third stages are the easiest to understand and implement and are generally sufficient for the majority of applications. Although higher levels of normalization are possible, they’re usually ignored by all but the most experienced and fastidious developers.

To illustrate the normalization process, we’ll use a little database that a book wholesaler might use to track book orders placed by small bookstores in the local area. This database must handle the following information:

• Book title

• ISBN

• Author

• Publisher

• Publisher address

• Publisher city

• Publisher state

• Publisher zip code

• Publisher phone number

• Publisher fax

• Customer name

• Customer address

• Customer city

• Customer state

• Customer zip code

• Customer phone number

Although this data set is very simple, it’s typical of the type of data you might manage with an Access database application, and it provides us with a valid demonstration of normalizing a set of data.

First normal form

The initial stage of normalization, called first normal form, requires that the table conform to the following rule:

Each cell of a table must contain only a single value and the table must not contain repeating groups of data.

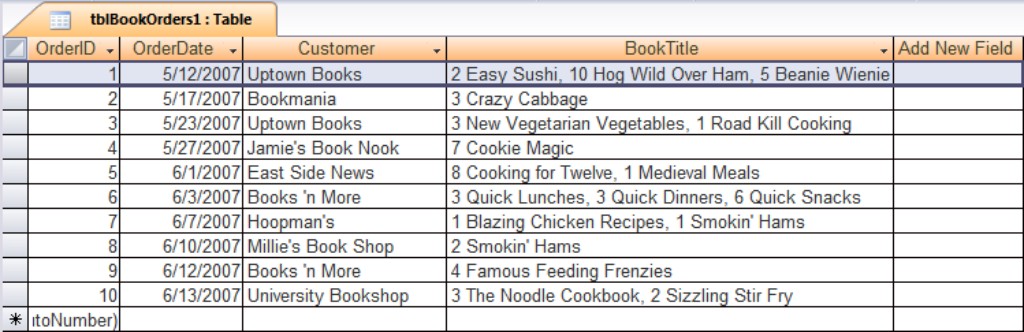

A table is meant to be a two-dimensional storage object, and storing multiple values within a field or permitting repeating groups within the table implies a third dimension to the data. Figure 3-2 shows the first attempt (tblBookOrders1) at building a table to manage bookstore orders. Notice that some bookstores have ordered more than one book. A value like 7 Cookie Magic in the BookTitles field means that the contact has ordered seven copies of the cookbook titled Cookie Magic.

Figure 3-2

An unnormalized tblBookOrders table

The table in Figure 3-2 is typical of a flat-file approach to building a database. Data in a flat-file database are stored in two dimensions (rows and columns) and neglects the third dimension (related tables) possible in a relational database system such as Microsoft Access.

Notice how the table in Figure 3-2 violates the first rule of normalization. Many of the records in this table contain multiple values in the BookTitle field. For instance, the book titled Smokin’ Hams appears in records 7 and 8. There is no way for the database to handle this data easily. For instance, if you want to cross-reference the books ordered by the bookstores, you’d have to parse the data contained in the BookTitle field to determine which books have been ordered by which contacts.

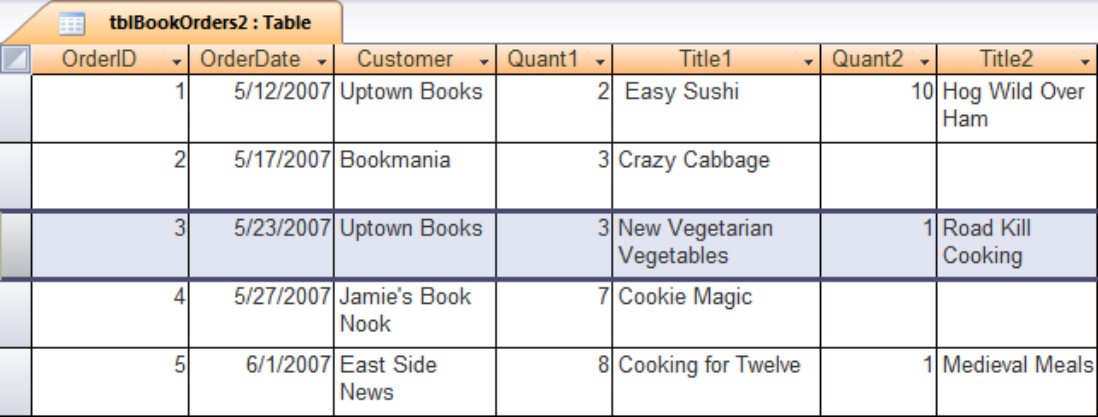

A slightly better design is shown in Figure 3-3 (tblBookOrders2). The books’ quantities and titles have been separated into individual columns. This arrangement makes it somewhat easier to retrieve quantity and title information, but the repeating groups for quantity and title continue to violate the first rule of normalization. (The row height in Figure 3-3 has been adjusted to make it easier for you to see the table’s arrangement.)

Figure 3-3

Only a slight improvement over the previous design

The design in Figure 3-3 is still clumsy and difficult to work with. The columns to hold the book quantities and titles are permanent features of the table. The developer must add enough columns to accommodate the maximum number of books that could be purchased by a bookstore. For instance, let’s assume the developer anticipates no bookstore will ever order more than 50 books at a time. This means that 100 columns would have to be added to the table (two columns—Quantity and Title—are required for each book title ordered). If a bookstore orders a single book, 98 columns would sit empty in the table, a very wasteful and inefficient situation.

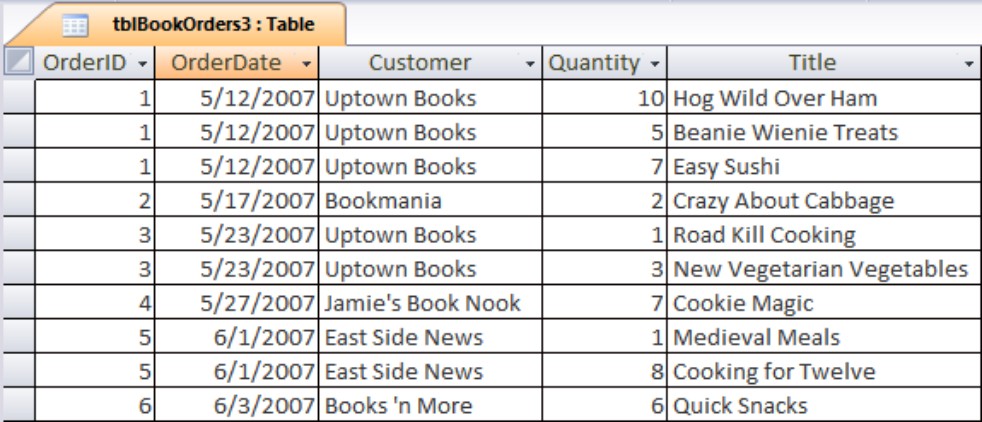

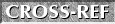

Figure 3-4 shows tblBookOrders, a table in first normal form (abbreviated 1NF). Instead of stacking multiple book orders within a single record, a second table is produced in which each record contains a single book ordered by a contact. More records are required, but the data are handled much more easily. First normal form is much more efficient because the table contains no unused fields. Every field is meaningful to the table’s purpose.

Figure 3-4

First normal form at last!

The table shown in Figure 3-4 contains the same data as shown in Figure 3-2 and Figure 3-3. The new arrangement, however, makes it much easier to work with the data. For instance, queries are easily constructed to return the total number of a particular book ordered by contacts, or to determine which titles have been ordered by a particular bookstore.

Your tables should always be in first normal form. Make sure each cell of the table contains a single value, and don’t mix values within a cell.

The table design optimization is not complete at this point, however. Much remains to be done with the BookOrders data and the other tables in this application. In particular, the table shown in Figure 3-4 contains a lot of redundant information. The book titles are repeated each time customers order the same book, and the order number and order date are repeated for each row containing information about an order.

A more subtle error is the fact that the OrderID can no longer be used as the table’s primary key. Because the Order ID is duplicated for each book title in an order, it cannot be used to identify each record in the table. Instead, the OrderID field is now just a key field for the table and can be used to locate all of the records relevant to a particular order. The next step of optimization corrects this situation.

Second normal form

A more efficient design results from splitting the data in tblBookOrders into two different tables to achieve second normal form (2NF). The first table contains the order information (for instance, the OrderID, OrderDate and Customer ) while the second table contains the order details (Quantity and Title). This process is based on the second rule of normalization:

Data not directly dependent on the table’s primary key is moved into another table.

This rule means that a table should contain data that represents a single entity. The table in Figure 3-4 violates this rule of normalization because the individual book titles do not depend on the table’s key field, the OrderID. Each record is a mix of book and order information. (For the meantime, we’re ignoring the fact that this table does not contain a primary key. We’ll be adding primary keys in a moment.)

At first glance, it may appear as though the book titles are indeed dependent on the Order ID. After all, the reason the book titles are in the table is because they’re part of the order. However, a moment’s thought will clarify the violation of second normal form. The title of a book is completely independent of the book order in which it is included. The same book title appears in multiple book orders; therefore, the Order ID has nothing to do with how a book is named. Given an arbitrary Order ID, you cannot tell anything about the books contained in the order other than looking at the Orders table.

The Order Date, however, is completely dependent on the Order ID. For each Order ID there is one and only one Order Date. Therefore, any Order Date is dependent on its associated Order ID. Order Dates may be duplicated in the table, of course, because multiple orders may be received on the same day. For each Order ID, however, there is one and only one valid Order Date value.

Second normal form often means breaking up a monolithic table into constituent tables, each of which contains fewer fields than the original table. In this example, second normal form is achieved by breaking the books and orders table into separate Orders and OrderDetails tables.

The order-specific information (such as the order date, customer, payment, and shipping information) goes into the Orders table, while the details of each order item (book, quantity, selling price, and so on) are contained by the OrderDetails table (not all of this data are shown in our example tables).

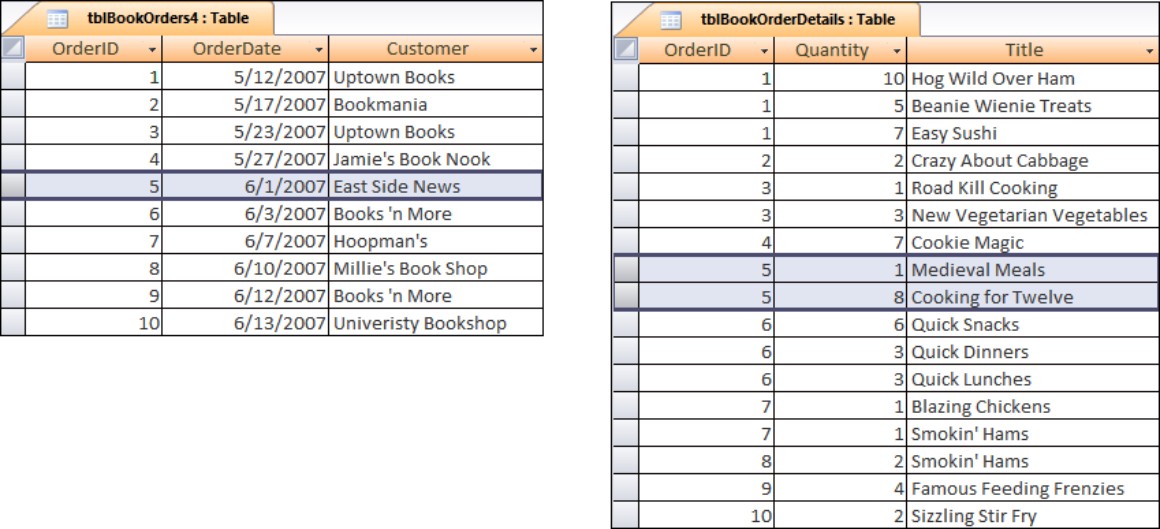

The new tables are shown in Figure 3-5. The OrderID is the primary key for the tblBookOrders4 table. The OrderID field in the tblBookOrderDetails is a foreign key that references the OrderID primary key field in tblBookOrders4. Each field in tblBookOrders4 (OrderDate and Customer) is said to be dependent on the table’s primary key.

Figure 3-5

Second normal form: The OrderID field connects these tables together in a one-to-many relationship.

The tblBookOrders4 and tblBookOrderDetails are joined in a one-to-many relationship. tblBookOrderDetails contains as many records for each order as are necessary to fulfill the requirements of the order. The OrderID field in tblBookOrders4 is now a true primary key. Each field in tblBookOrders4 is dependent on the OrderID field and appears only once for each order that is placed. The OrderID field in tblBookOrderDetails does not serve as the primary key for tblBookOrderDetails. In fact, tblBookOrderDetails does not even have a primary key, but one could be easily added.

The data in tblBookOrders4 and tblBookOrderDetails can be easily updated. If a bookstore cancels a particular book title in an order, the corresponding record is deleted from tblBookOrderDetails. If, on the other hand, a bookstore adds to an order, a new record can be added to tblBookOrderDetails to accommodate an additional title, or the Quantity field can be modified to increase or decrease the number of books ordered.

Breaking a table into individual tables that each describes some aspect of the data is called decomposition, a very important part of the normalization process. Even though the tables appear smaller than the original table (shown in Figure 3-2), the data contained within the tables are the same as before.

It’s easy to carry decomposition too far—create only as many tables as are required to fully describe the dataset managed by the database. When decomposing tables, be careful not to lose data. For instance, if the tblBookOrders4 table contained a SellingPrice field, you’d want to make sure that field was moved into tblBookOrderDetails.

Later, you’ll be able to use queries to recombine the data in tblBookOrders4 and tblBookOrderDetails in new and interesting ways. You’ll be able to determine how many books of each type have been ordered by the different customers, or how many times a particular book has been ordered. When coupled with a table containing information such as book unit cost, book selling price, and so on, the important financial status of the book wholesaler becomes clear.

Notice also that the number of records in tblBookOrders4 has been reduced. This is one of several advantages to using a relational database. Each table contains only as much data as is necessary to represent the entity (in this case, a book order) described by the table. This is far more efficient than adding duplicate field values (refer to Figure 3-2) for each new record added to a table.

Further optimization: Adding tables to the scheme

The design shown in Figure 3-5 is actually pretty good. Yet, we could still do more to optimize this design. Consider the fact that the entire name of each customer is stored in tblBookOrders4. Therefore, a customer’s name appears each time the customer has placed an order. Notice that Uptown Books has placed two orders during the period covered by tblBookOrders4. If the Uptown Books bookstore changed its name to Uptown Books and Periodicals, you’d have to go back to this table and update every instance of Uptown Books to reflect the new name.

Overlooking an instance of the customer’s name during this process is called an update anomaly and results in records that are inconsistent with the other records in the database. From the database’s perspective, Uptown Books and Uptown Books and Periodicals are two completely different organizations, even if we know that they’re the same store. A query to retrieve all of the orders placed by Uptown Books and Periodicals will miss any records that still have Uptown Books in the Customer field because of the update anomaly.

Also, the table lacks specific information about the customers. No addresses, phone numbers, or other customer contact information are contained in tblBookOrders4. Although you could use a query to extract this information from a table named tblBookStores containing the addresses, phone numbers, and other information about the bookstore customers, using the customer name (a text field) as the search key is much slower than using a numeric key in the query.

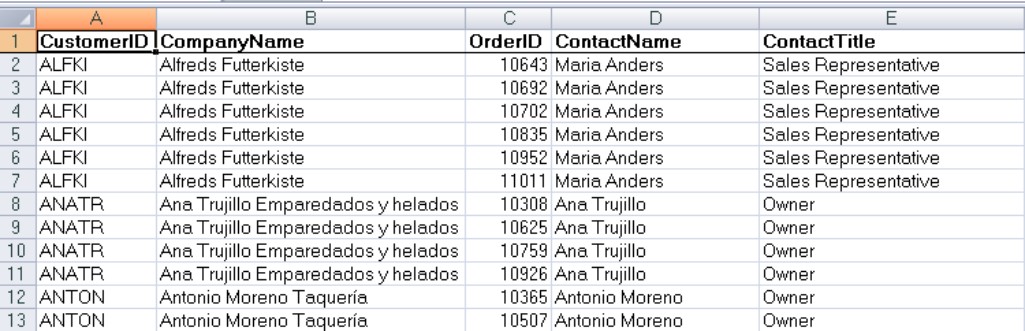

Figure 3-6 shows the results of a refinement of the database design: tblBookOrders5contains a foreign key named CustomerID that relates to the CustID primary key field in the tblBookStores table. This arrangement uses tblBookStores as a lookup table to provide information to a form or report.

Figure 3-6

The numeric CustomerID field results in faster retrievals from tblCustomers.

Part of the speed improvement is due to the fact that the CustomerID field in tblBookOrders5 is a long integer (4-byte) value instead of a text field. This means that Access has to manipulate only 4 bytes of memory when searching tblBookOrders5. The Customer field in tblBookOrders4 was a text field with a width of 50 characters. This means that Access might have to manipulate as many as 50 bytes of memory when searching for matching records in tblCustomers.

A second advantage of removing the customer name from the orders table is that the name now exists in only one location in the database. If Uptown Books changes its name to Uptown Books and Periodicals, we now only have to change its entry in the tblBookStores table. This single change is reflected throughout the database, including all forms and reports that use the customer name information.

Breaking the rules

From time to time, you may find it necessary to break the rules. For instance, let’s assume the bookstores are entitled to discounts based on the volume of purchases over the last year. Strictly following the rules of normalization, the discount percentage should be included in the tblCustomers table. After all, the discount is dependent on the customer, not on the order.

But maybe the discount applied to each order is somewhat arbitrary. Maybe the book wholesaler permits the salespeople to cut special deals for valued customers. In this case, you might want to include a Discount column in the book orders table, even if it contains duplicate information in many records. You could store the traditional discount as part of the customer’s record in tblCustomers, and use it as the default value for the Discount column but permit the salesperson to override the discount value when a special arrangement has been made with the customer.

Third normal form

The last step of normalization, called third normal form (3NF), requires removing all fields that can be derived from data contained in other fields in the table or other tables in the database. For instance, assume the sales manager insists that you add a field to contain the total value of a book order in the orders table. This information, of course, would be calculated from the book quantity field in tblOrderDetails and the book unit price from the book information table.

There’s no reason why you should add the new OrderTotal field to the Orders table. Access easily calculates this value from data that are immediately available in the database. The only advantage of storing order totals as part of the database is to save the few milliseconds required for Access to retrieve and calculate the information when the calculated data are needed by a form or report.

Removing calculated data has little to do with maintaining the database. The main benefit is saving disk space and memory, and reducing network traffic. Depending on the applications you build, you may find good reasons to store calculated data in tables, particularly if performing the calculations is a lengthy process, or if the stored value is necessary as an audit check on the calculated value printed on reports. It may be more efficient to perform the calculations during data entry (when data are being handled one record at a time) rather than when printing reports (when many thousands of records are manipulated to produce a single report).

Although higher levels of normalization are possible, you’ll find that for most database applications, third normal form is more than adequate. At the very least, you should always strive for first normal form in your tables by moving redundant or repeating data to another table.

More on anomalies

This business about update anomalies is important to keep in mind. The whole purpose of normalizing the tables in your databases is to achieve maximum performance with minimum maintenance effort.

Three types of errors can occur from an unnormalized database design. Following the rules outlined in this chapter will help you avoid the following pitfalls:

• Insertion anomaly: An error occurs in a related table when a new record is added to another table. For instance, let’s say you’ve added the OrderTotal field described in the previous section. After the order has been processed, the customer calls and changes the number of books ordered or adds a new book title to the same order. Unless you’ve carefully designed the database to automatically update the calculated OrderTotal field, the data in that field will be in error as the new data are inserted into the table.

• Deletion anomaly: A deletion anomaly causes the accidental loss of data when a record is deleted from a table. Let’s assume that the tblBookOrders table contains the name, address, and other contact information for each bookstore. Deleting the last remaining record containing a particular customer’s order causes the customer’s contact information to be unintentionally lost. Keeping the customer contact information in a separate table preserves and protects that data from accidental loss. Avoiding deletion anomalies is one good reason not to use cascading deletes in your tables (see “Table Relationships,” later in this chapter, for more on cascading deletes).

• Update anomaly: Storing data that are not dependent on the table’s primary key causes you to have to update multiple rows anytime the independent information changes. Keeping the independent data (such as the bookstore information) in its own table means that only a single instance of the information needs to be updated. (For more on update anomalies, see “Further optimization: Adding tables to the scheme” earlier in this chapter.)

Denormalization

After hammering you with all the reasons why normalizing your databases is a good idea, let’s consider when you might deliberately choose to denormalize tables or use unnormalized tables.

Generally speaking, you normalize data in an attempt to improve the performance of your database. For instance, in spite of all your efforts, some lookups will be time-consuming. Even when using carefully indexed and normalized tables, some lookups require quite a bit of time, especially when the data being looked up are complicated or there’s a large amount of it.

Similarly, some calculated values may take a long time to evaluate. You may find it more expedient to simply store a calculated value than to evaluate the expression on the fly. This is particularly true when the user base is working on older, memory-constrained, or slow computers.

Be aware that most steps to denormalize a database schema result in additional programming time required to protect the data and user from the problems caused by an unnormalized design. For instance, in the case of the calculated Order Total field, you must insert code that calculates and updates this field whenever the data in the fields underlying this value change. This extra programming, of course, takes time to implement and time to process at runtime.

You must be careful, of course, to see that denormalizing the design does not cause other problems. If you know you’ve deliberately denormalized a database design and are having trouble making everything work (particularly if you begin to encounter any of the anomalies discussed in the previous section), look for workarounds that permit you to work with a fully normalized design.

Finally, always document whatever you’ve done to denormalize the design. It’s entirely possible that you or someone else will be called in to provide maintenance or to add new features to the application. If you’ve left design elements that seem to violate the rules of normalization, your carefully considered work may be undone by another developer in an effort to “optimize” the design. The developer doing the maintenance, of course, has the best of intentions, but he may inadvertently reestablish a performance problem that was resolved through subtle denormalization.

Table Relationships

Many people start out using a spreadsheet application like Excel or Lotus 1-2-3 to build a database. Unfortunately, a spreadsheet stores data as a two-dimensional worksheet (rows and columns) with no easy way to connect individual worksheets together. You must manually connect each cell of the worksheet to the corresponding cells in other worksheets—a tedious process at best.

Two-dimensional storage objects like worksheets are called flat-file databases because they lack the three-dimensional quality of relational databases. Figure 3-7 shows an Excel worksheet used as a flat-file database.

Figure 3-7

An Excel worksheet used as a flat-file database

The problems with flat-file databases should be immediately apparent from viewing Figure 3-7. Notice that the customer information is duplicated in multiple rows of the worksheet. Each time a customer places an order, a new row is added to the worksheet. In this particular instance, only the order number is recorded as part of the worksheet, although the entire order could be included in the worksheet, including the order details. Obviously, this worksheet would rapidly become unmanageably large and unwieldy.

Consider the amount of work required to make relatively simple changes to the data in Figure 3-7. For instance, changing a customer’s address would require searching through numerous records and editing the data contained within individual cells, creating many opportunities for errors.

Through clever programming in the Excel VBA language, it would be possible to link the data in the worksheet shown in Figure 3-7 with another worksheet containing the order detail information. It would also be possible to programmatically change data in individual rows. But such Herculean efforts are needless when you harness the power of a relational database system such as Microsoft Access.

Connecting the data

Recall that a table’s primary key uniquely identifies the records in a table. Example primary keys for a table of employee data include the employee’s Social Security number, a combination of first and last names, or an employee ID. Let’s assume the employee ID is selected as the primary key for the employees table. When the relationship to the payroll table is formed, the EmployeeID field is used to connect the tables together. Figure 3-8 shows this sort of arrangement (see the “One-to-many” section, later in this chapter).

Figure 3-8

The relationship between the tblEmployees and tblPayroll tables is an example of a typical one-to-many relationship.

Although you can’t see the relationship in Figure 3-8, Access knows it’s there and is able to instantly retrieve all of the records from tblPayroll for any employee in tblEmployees.

The relationship example shown in Figure 3-8, in which each record of tblEmployees is related to several records in tblPayroll, is the most common type found in relational database systems but is by no means the only way that data in tables are related. This book, and most books on relational databases such as Access, discuss the three basic types of relationships between tables:

• One-to-one

• One-to-many

• Many-to-many

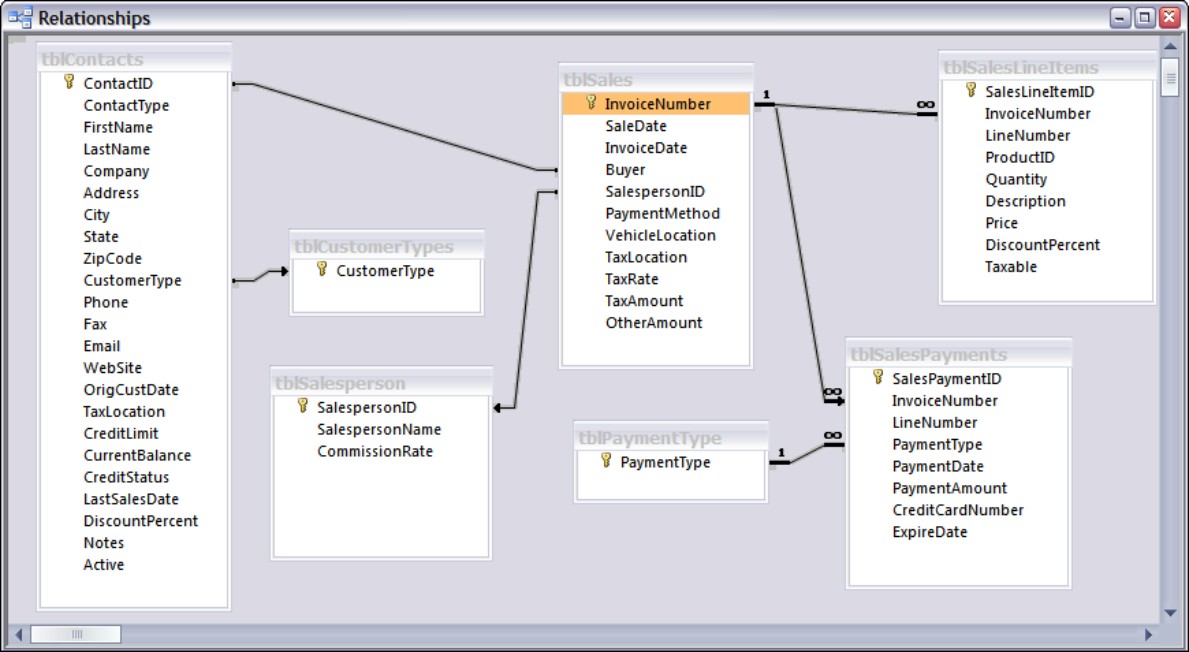

Figure 3-9 shows the relationships in the completed Access Auto Auctions database.

Figure 3-9

The Access Auto Auctions tables relationships

Notice that there are three one-to-many relationships between the primary tables (tblSales- to-tblSalesPayments, tblSales-to-tblSalesLineItems, and tblContacts- to-tblContactsLog), two one-to-many relationship between the primary tables (tblSalesLineItems-to-tblProducts and tblSales-to-tblContacts), and five one-to-many relations between the five lookup tables and the primary tables. The relationship that you specify between tables is important. It tells Access how to find and display information from fields in two or more tables. The program needs to know whether to look for only one record in a table or look for several records on the basis of the relationship. The tblSales table, for example, is related to the tblContacts table as a many-to-one relationship. This is because the focus of the Access Auto Auctions system is the sales. This means that there will always be only one contact (buyer) related to every sales record; that is, many sales can be associated with a single buyer (contact). In this case, the Access Auto Auctions system is actually using tblContacts as a lookup table.

Relationships can be very confusing; it all depends upon the focus of the system. For instance, when working with the tblContacts and tblSales tables, you can always create a query that has a one-to-many relationship to the tblSales table, from the tblContacts. Although the system is concerned with sales (invoices), there are times that you will want to produce reports or views that are buyer-related instead of invoice-related. Because one buyer can have more than one sale, there will always be one record in the tblContacts table for at least one record in the tblSales table; there could be many related records in the tblSales table. So Access knows to find only one record in the customer table and to look for any records in the sales table (one or more) that have the same customer number.

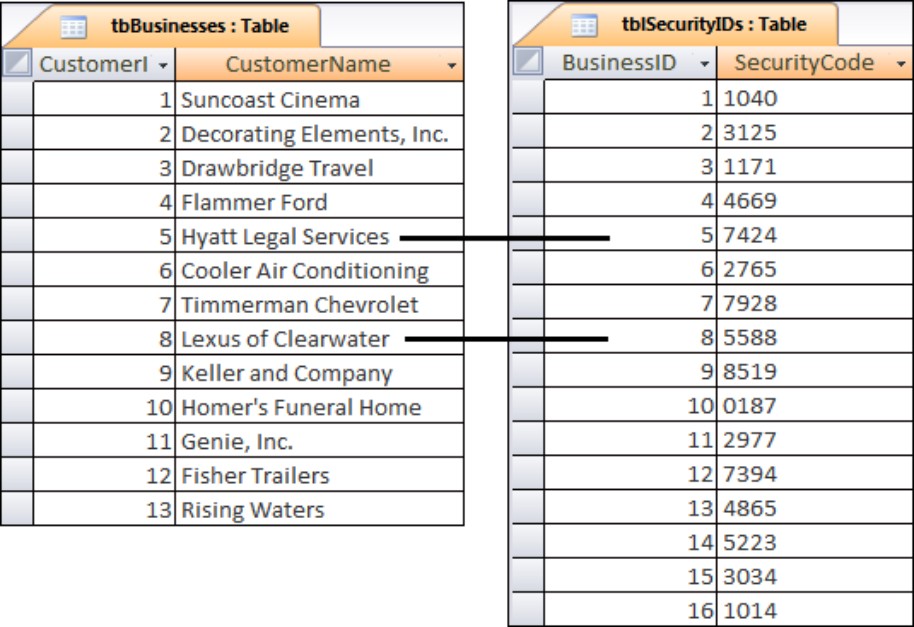

One-to-one

A one-to-one relationship between tables means that for every record in the first table, one and only one record exists in the second table. Figure 3-10 illustrates this concept.

Figure 3-10

A one-to-one relationship

Pure one-to-one relationships are not common in relational databases. In most cases, the data contained in the second table are most often included in the first table. As a matter of fact, one-to-one relationships are generally avoided because they violate the rules of normalization. Following the rules of normalization, data should not be split into multiple tables if the data describe a single entity. Because a person has one and only one birth date, the birth date should be included in the table containing a person’s other data.

There are times, however, when it’s not advisable to store certain data along with other data in the table. For instance, consider the situation illustrated in Figure 3-10. The data contained in tblSecurity are confidential. Normally, you wouldn’t want anyone with access to the public customer information (name, address, and so on) to have access to the confidential security code that the customer uses for purchasing or billing purposes. If necessary, the tblSecurity table could be located on a different disk somewhere on the network, or even maintained on removable media to protect it from unauthorized access.

Another instance of a one-to-one relationship is a situation where the data in a table exceed the 255-field limit imposed by Access. Although they’re rare, there could be cases where you may have too many fields to be contained within a single table. The easiest solution is simply to split the data into multiple tables and connect the tables through the primary key (using the same key value, of course, in each table).

Yet another situation is where data are being transferred or shared between databases. Perhaps the shipping clerk in an organization doesn’t need to see all of a customer’s data. Instead of including irrelevant information such as job titles, birth dates, alternate phone numbers, and e-mail addresses, the shipping clerk’s database contains only the customer’s name, address, and other shipping information. A record in the customer table in the shipping clerk’s database has a one-to-one relationship with the corresponding record in the master customer table located on the central computer somewhere within the organization. Although the data are contained within separate .accdb files, the links between the tables can be live, meaning that changes to the master record are immediately reflected in the shipping clerk’s .mdb file.

Tables joined in a one-to-one relationship will almost always have the same primary key—for instance, OrderID or EmployeeNumber. There are very few reasons you would create a separate key field for the second table in a one-to-one relationship.

One-to-many

A far more common relationship between tables in a relational database is the one-to-many. In one-to-many relationships, each record in the first table (the parent) is related to one or more records in the second table (the child). Each record in the second table is related to one and only one record in the first table. Without a doubt, one-to-many relationships are the most common type encountered in relational database systems. Examples of one-to-many situations abound:

• Customers and orders: Each customer (the “one” side) has placed several orders (the “many” side), but each order is sent to a single customer.

• Teacher and student: Each teacher has many students, but each student has a single teacher (within a particular class, of course).

• Employees and paychecks: Each employee has received several paychecks, but each paycheck is given to one and only one employee.

• Patients and treatments: Each patient receives zero or more treatments for a disease.

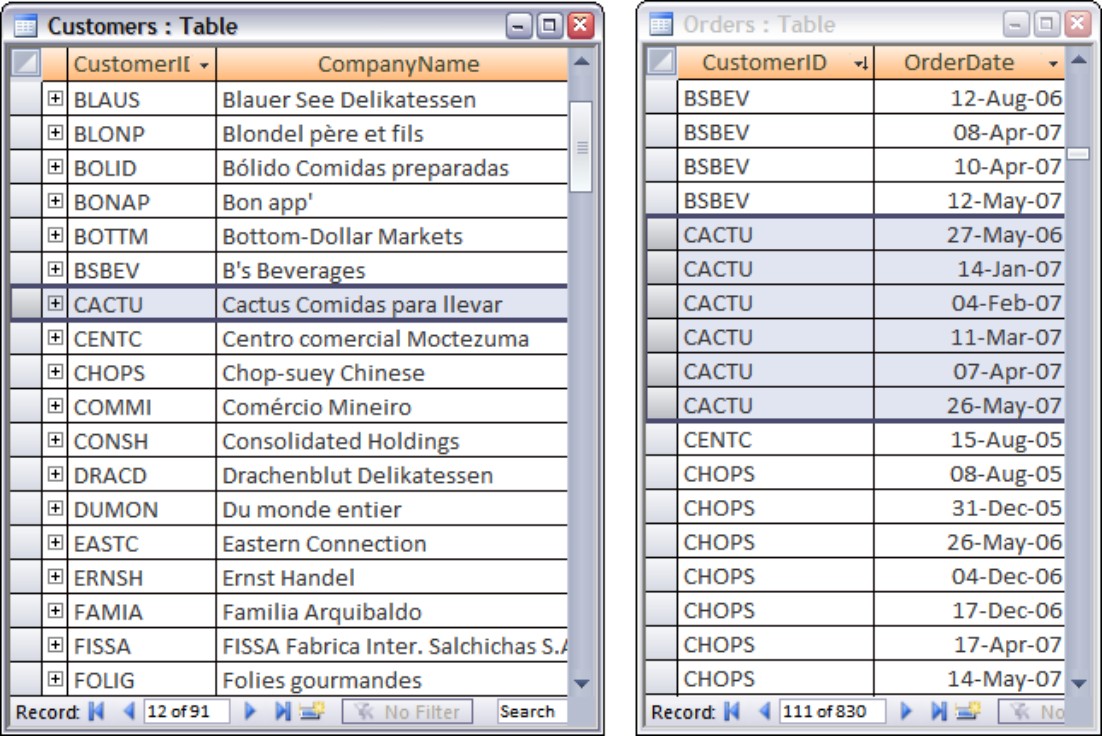

As we discuss in the “Creating relationships and enforcing referential integrity” section, later in this chapter, Access makes it very easy to establish one-to-many relationships between tables. A one-to-many relationship is illustrated in Figure 3-11. This figure, using tables from the Northwind Traders database, clearly demonstrates how each record in the Customers table is related to several different records in the Orders table. An order can be sent to only a single customer, so all requirements of one-to-many relationships are fulfilled by this arrangement.

Figure 3-11

The Northwind Traders database contains many examples of one-to-many relationships.

Although the records on the “many” side of the relationship illustrated in Figure 3-11 are sorted by the CustomerID field in alphabetical order, there is no requirement that the records in the many table be arranged in any particular order.

Although parent-child is the most common expression used to explain the relationship between tables related in a one-to-many relationship, you may hear other expressions used, such as master-detail applied to this design. The important thing to keep in mind is that the intent of referential integrity is to prevent lost records on the “many” side of the relationship. Referential integrity guarantees that there will never be an orphan, a child record without a matching parent record. As you’ll soon see, it is important to keep in mind which table is on the “one” side and which is on the “many” side.

Notice how difficult it would be to record all of the orders for a customer if a separate table were not used to store the order’s information. The flat-file alternative discussed in the “Table Relationships” section, earlier in this chapter, requires much more updating than the one-to-many arrangement shown in Figure 3-11. Each time a customer places an order with Northwind Traders a new record is added to the Orders table. Only the CustomerID (for instance, CACTU) is added to the Orders table as the foreign key back to the Customers table. Keeping the customer information is relatively trivial because each customer record appears only once in the Customers table.

Many-to-many

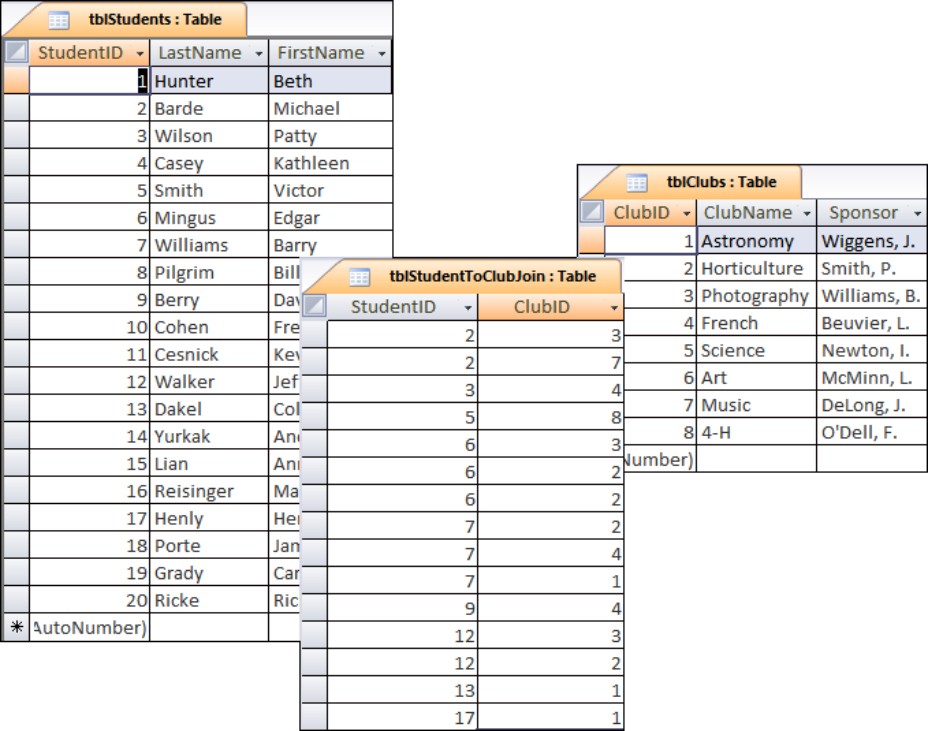

You’ll come across many-to-many situations from time to time. In a many-to-many arrangement, each record in both tables can be related to zero, one, or many records in the other table. An example is shown in Figure 3-12. Each student in tblStudents can belong to more than one club, while each club in tblClubs has more than one member.

Figure 3-12

A database of students and the clubs they belong to is an example of a many-to-many relationship.

As indicated in Figure 3-12, many-to-many relationships are somewhat more difficult to understand because they cannot be directly modeled in relational database systems like Access. Instead, the many-to-many relationship is broken into two separate one-to-many relationships, joined through a linking, or join, table. The join table has one-to-many relationships with both of the tables involved in the many-to-many relationship. This principle can be a bit confusing at first, but close examination of Figure 3-12 soon reveals the beauty of this arrangement.

In Figure 3-12, you can easily see that student ID 2 (Michael Barde) belongs to the music club, while student ID 12 (Jeffrey Wilson) is a member of the horticulture club. Both Michael Barde and Jeffrey Wilson belong to the photography club. Each student belongs to multiple clubs, and each club contains multiple members.

Because of the additional complication of the join table, many-to-many relationships are often considered more difficult to establish and maintain. Fortunately, Access makes such relationships quite easy to establish, once a few rules are followed. These rules are explained in various places in this book. For instance, in order to update either side of a many-to-many relationship (for example, to change club membership for a student), the join table must contain the primary keys of both tables joined by the relationship.

Many-to-many relationships are quite common in business environments:

• Lawyers to clients (or doctors to patients): Each lawyer may be involved in several cases, while each client may be represented by more than one lawyer on each case.

• Patients and insurance coverage: Many people are covered by more than one insurance policy. For instance, if you and your spouse are both provided medical insurance by your employers, you have multiple coverage.

• Video rentals and customers: Over a year’s time, each video is rented by several people, while each customer rents several videos during the year.

• Magazine subscriptions: Most magazines have circulations measured in the thousands or millions. Most people subscribe to more than one magazine at a time.

The Access Auto Auctions database has a many-to-many relationship between tblContacts and tblSalesPayments, linked through tblSales. Each customer may have purchased more than one item, and each item may be paid for through multiple payments. In addition to joining contacts and sales payments, tblSales contains other information, such as the sale date and invoice number. The join table in a many-to-many relationship often contains information regarding the joined data.

Given how complicated many-to-many joins can be to construct, it is fortunate that many-to-many relationships are quite a bit less common than straightforward one-to-many situations.

Although Figure 3-12 shows a join table with just two fields (StudentID and ClubID), there is no reason that the join table cannot contain other information. For instance, the tblStudentToClubJoin table might include fields to indicate membership dues collected from the student for each club.

Pass-through

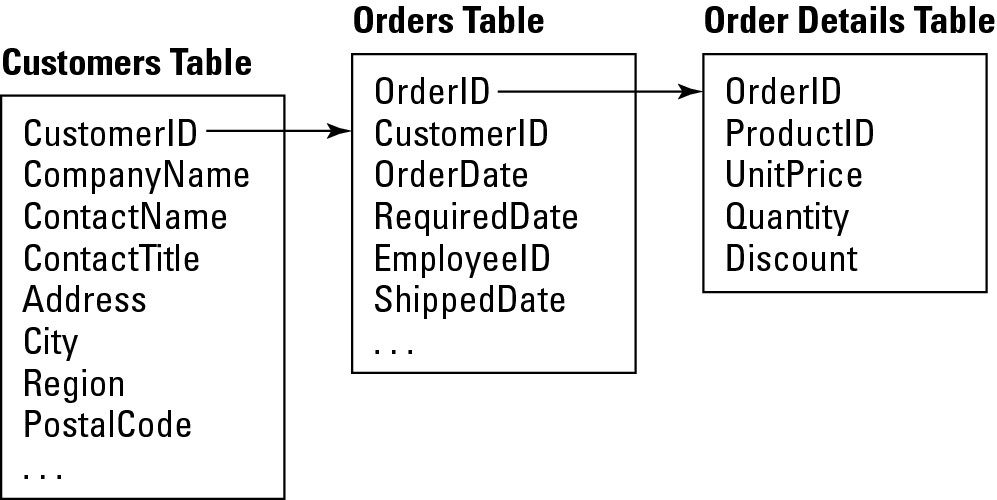

The last type of relationship we’ll explore involves more than one table. Much as a many-to-many relationship involves an intermediate table, a pass-through relationship (which is sometimes called a grandparent-grandchild relationship) is necessary in some situations. In this type of relationship, the data in the grandparent table are related to records in a grandchild table through a third table. An example taken from Northwind Traders is diagrammed in Figure 3-13.

Figure 3-13

The order details information is related to the Customers table through the Orders table.

There is no direct connection between the Customers table (the grandparent) and the Order Details table (the grandchild). The Order Details table contains all of the information on the specific items included in a particular order. As indicated by Figure 3-13, you must use the Orders table (the parent table) to determine how many of a particular item have been purchased by a customer.

The only way to get information from the OrderDetails grandchild table is to first use the CustomerID field to reference all of the associated records in the Orders table. Then use the OrderID field to find all of its related items in the OrderDetails table.

From time to time, you’ll find yourself building Access queries to extract just this kind of information. When you build these queries, you’re actually constructing a pass-through relationship between the tables involved in the query.

The relationship between any two of the tables involved in the pass-through relationship (Customers to Orders or Orders to OrderDetails) is a one-to-many relationship.

Integrity Rules

Access permits you to apply referential integrity rules that protect data from loss or corruption. The relational model defines several rules meant to enforce the referential integrity requirements of relational databases. In addition, Access contains its own set of referential integrity rules that are enforced by the Jet database engine. Referential integrity means that the relationships between tables are preserved during updates, deletions, and other record operations.

Imagine a payroll application that contained no rules regulating how data in the database are used. It’d be possible to issue payroll checks that are not linked to an employee, or to have an employee who had never been issued a paycheck. From a business perspective, issuing paychecks to “phantom” employees is much more serious than having an employee who’s never been paid! After all, the unpaid employee will soon complain about the situation, but paychecks issued to phantom employees raise no alarms. At least, that is, until the auditors step in and notify management of the discrepancy.

A database system must have rules that specify certain conditions between tables—rules to enforce the integrity of relationships between the tables. These rules are known as referential integrity; they keep the relationships between tables intact in a relational database management system. Referential integrity prohibits you from changing your data in ways that invalidate the relationships between tables.

Referential integrity operates strictly on the basis of the tables’ key fields; it checks each time a key field, whether primary or foreign, is added, changed, or deleted. If a change to a value in a key field creates an invalid relationship, it is said to violate referential integrity. Tables can be set up so that referential integrity is enforced automatically.

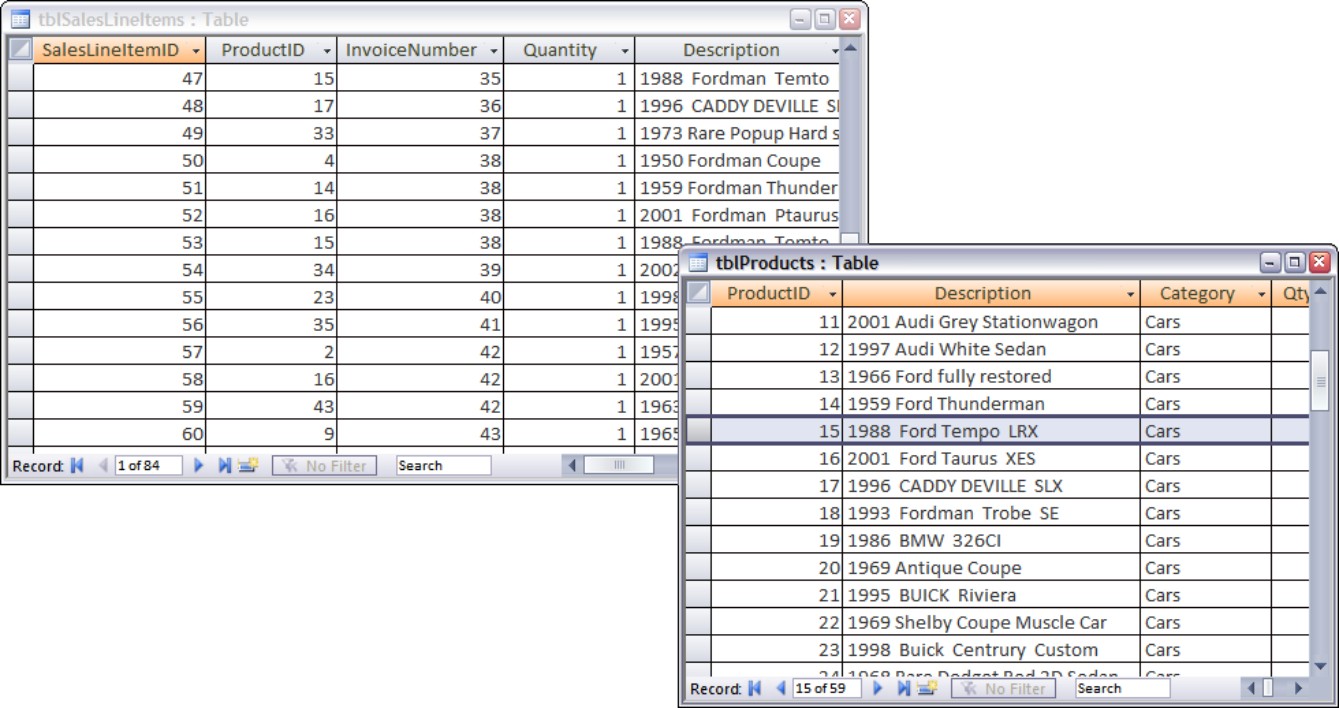

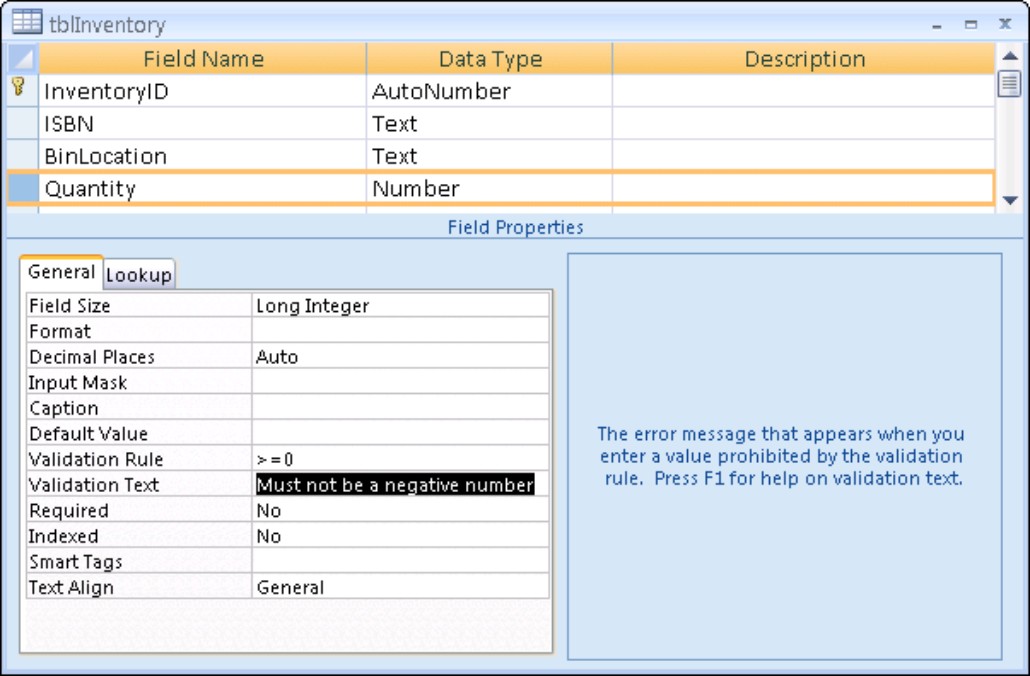

Figure 3-14 illustrates one of several relationships in the Access Auto Auctions database. The Products table is related to the SalesLinesItem table through the ProductID field. The ProductID field in tblProducts is that table’s primary key, while the ProductID field in tblSalesLineItems is a foreign key. The relationship connects each product with a line item on a sales invoice. In this relationship, tblProducts is the parent table, while tblSalesLineItems is the child table.

Figure 3-14

A typical database relationship

Orphaned records are very bad in database applications. Because payroll information is almost always reported as which paychecks were issued to which employees, a paycheck that is not linked to an employee will not be discovered under most circumstances. It’s easy to know which paychecks were issued to John Doe, but given an arbitrary paycheck record, it may not be easy to know that there is no legitimate employee matching the paycheck.

Because the referential integrity rules are enforced by the Access database engine, data integrity is ensured wherever the data appear in the database: in tables, queries, or forms. Once you’ve established the integrity requirements of your applications, you don’t have to be afraid that data in related tables will become lost or disorganized.

We can’t overemphasize the need for referential integrity in database applications. Many developers feel that they can use VBA code or user interface design to prevent orphaned records. The truth is that, in most databases, the data stored in a particular table may be used in many different places within the application. Also, given the fact that many database projects extend over many years, and among any number of developers, it’s not always possible to recall how data should be protected. By far, the best approach to ensuring the integrity of data stored in any database system is by utilizing the power of the database engine to enforce referential integrity.

The general relational model referential integrity rules ensure that records contained in relational tables are not lost or confused. For obvious reasons, it is important that the primary keys connecting tables be protected and preserved. Also, changes in a table that affect other tables (for instance, deleting a record on the “one” side of a one-to-many relationship) should be rippled to the other tables connected to the first table. Otherwise, the data in the two tables will quickly become unsynchronized.

The first referential integrity rule states that no primary key can contain a null value. A null value is one that simply does not exist. The value of a field that has never been assigned a value (even a default value) is null. No row in a database table can have null in its primary key field because the primary purpose of the primary key is to guarantee uniqueness of the row. Obviously, null values cannot be unique and the relational model would not work if primary keys could be null.

Access automatically enforces the first referential integrity rule. As you add data to tables, you can’t leave the primary key field empty without generating a warning (one reason the AutoNumber field works so well as a primary key). Once you’ve designated a field in an Access table as the primary key, Access will not let you delete the data in the field, nor will it allow you to change the value in the field so that it duplicates a value in another record.

When using a composite primary key made up of several fields, all of the fields in the composite key must contain values. None of the fields are allowed to be empty. The combination of values in the composite primary key must be unique.

The second referential integrity rule says that all foreign key values must be matched by corresponding primary keys. This means that every record in a table on the “many” side of a one-to-many relationship must have a corresponding record in the table on the “one” side of the relationship. A record on the “many” side of a relationship without a corresponding record on the “one” side is said to be orphaned and is effectively removed from the database schema. Identifying orphaned records in a database can be very difficult, so you’re better off avoiding the situation in the first place.

The second rule means that the following situations must be handled by the Jet engine:

• Rows cannot be added to a “many” side table (the child) if a corresponding record does not exist on the “one” side (the parent). If a child record contains a ParentID field, the ParentID value must match an existing record in the parent table.

• The primary key value in a parent table cannot be changed if the change would create orphaned child records.

• Deleting a row on the “one” side must not orphan corresponding records on the “many” side.

For instance, in our payroll example, the foreign key in each record in the tblPayChecks table (the “many” side) must match a primary key in tblEmployees. You cannot delete a record in tblEmployees (the “one” side) without deleting the corresponding records in tblPayChecks.

One of the curious results of the rules of referential integrity is that it is entirely possible to have a parent record that is not matched by any child records. Intuitively, this makes sense. A company may certainly have employees who haven’t yet been issued paychecks. Or, the Access Auto Auctions company may recruit a new seller who doesn’t have any cars for sale at the moment. Eventually, of course, most parent records are matched by one or more child records, but this condition is not a requirement of relational databases.

A somewhat less obvious outcome of these rules is that it is possible to have a child record that is not matched by a parent record, as long as the parent foreign key field does not contain a value. As you will recall, referential integrity requires that any value in a child table’s foreign key field must be matched by the same value in the parent table. However, if the foreign key field in a child record is completely empty, there is no violation of referential integrity between the tables.

In practical terms, this situation is quite rare in Access applications. Virtually all database fields have some default value, such as zero, or an empty string (“”). In the case of a numeric foreign key, by default, Access inserts zero into the field as new records are added to the table. Unless zero appears somewhere in the parent table, a referential integrity violation exists, and the new record will not be added. The only way around this situation is to delete the default value of zero for the foreign key field, or to ensure that the foreign key value is set to a valid ParentID value before adding the new record to the child table.

As you’ll see in the next section, Access makes it easy to specify the integrity rules you want to employ in your applications. You should be aware, however, that not using the referential integrity rules means that you might end up with orphaned records and other data integrity problems.

Understanding Keys

When you create database tables, like those created in Chapter 2, you should assign each table a primary key. This key is a way to make sure that the table records contain only one unique value; for example, you may have several contacts named Michael Heinrich, and you may even have more than one Michael Heinrich (for instance, father and son) living at the same address. So in a case like this, you have to decide on how you can create a record in the Customer database that will let you identify each Michael Heinrich separately.

Uniquely identifying each record in a table is precisely what a primary key field does. For example, using the Access Auto Auction as an example, the ContactID field (a unique number that you assign to each customer or seller that comes into your office) is the primary key in the tblContacts table—each record in the table has a different ContactID number. (No two records have the same number.) This is important for several reasons:

• You do not want to have two records in your database for the same customer, because this can make updating the customer’s record virtually impossible.

• You want assurance that each record in the table is accurate, thus the information extracted from the table is accurate.

• You do not want to make the table (and its records) any larger than necessary.

The ability to assign a single, unique value to each record makes the table clean and reliable. This is known as entity integrity. By having a different primary key value in each record (such as the ContactID in the tblContacts table), you can tell two records (in this case, customers) apart, even if all other fields in the records are the same. This is important because you can easily have two individual customers with a common name, such as Fred Smith, in your table.

Theoretically, you could use the customer name and the customer’s address, but two people named Fred D. Smith could live in the same town and state, or a father and son (Fred David Smith and Fred Daniel Smith) could live at the same address. The goal of setting primary keys is to create individual records in a table that guarantees uniqueness.

If you don’t specify a primary key when creating Access tables, Access asks whether you want one. If you say yes, Access uses the AutoNumber data type to create a primary key for the table. An AutoNumber field automatically updates each time a record is added to the table, and cannot be changed once its value has been established. Furthermore, once an AutoNumber value has appeared in a table, the value will never be reused, even if the record containing the value is deleted and the value no longer appears in the table.

Deciding on a primary key

As you learned previously, a table normally has a unique field (or combination of fields)—the primary key for that table—which makes each record unique. The primary key is an identifier that is often a text or AutoNumber data type. To determine the contents of this ID field, you specify a method for creating a unique value for the field. Your method can be as simple as letting Access automatically assign a value or using the first letter of the real value you are tracking along with a sequence number (such as A001, A002, A003, B001, B002, and so on). The method may rely on a random set of letters and numbers for the field content (as long as each field has a unique value) or a complicated calculation based on information from several fields in the table.

Table 3-1 lists the Access Auto Auctions tables and describes one possible plan for deriving the primary key values in each table. As this table shows, it doesn’t take a great deal of work (or even much imagination) to derive a plan for key values. Any rudimentary scheme with a good sequence number always works. Access automatically tells you when you try to enter a duplicate key value. To avoid duplication, you can simply add the value of 1 to the sequence number.

Even though it is not difficult to use logic (implemented, perhaps, though VBA code) to generate unique values for a primary key field, by far the simplest and easiest approach is to use AutoNumber fields for the primary keys in your tables. The special characteristics of the AutoNumber field (automatic generation, uniqueness, the fact that it cannot be changed, and so on) make it the ideal candidate fore primary keys. Furthermore, an AutoNumber value is nothing more than a 4-byte integer value, making it very fast and easy for the database engine to manage. For all of these reasons, the Access Auto Auction exclusively uses AutoNumber fields as primary keys in its tables.

You may be thinking that all these sequence numbers make it hard to look up information in your tables. Just remember that, in most case, you never look up information by an ID field. Generally, you look up information according to the purpose of the table. In the tblContacts table, for example, you would look up information by customer name—last name, first name, or both. Even when the same name appears in multiple records, you can look at other fields in the table (zip code, phone number) to find the correct customer. Unless you just happen to know the contact ID number, you’ll probably never use it in a search for information.

Recognizing the benefits of a primary key

Have you ever placed an order with a company for the first time and then decided the next day to increase your order? You call the people at the order desk. They may ask you for your customer number. You tell them that you don’t know your customer number. Next, they ask you for some other information—generally, your zip code or telephone area code. Then, as they narrow down the list of customers, they ask your name. Once they’ve located you in their database, they can tell you your customer number. Some businesses use phone numbers or e-mail addresses as unique starting points.

Database systems usually have more than one table, and these tend to be related in some manner. For example, in the Access Auto Auctions database tblContacts and tblSales are related to each other via a link field named Buyer in tblSales and ContactID in tblContacts. The tblContacts table always has one record for each customer (buyer or seller), and the tblSales table has a record for the sales invoice that the customer makes (every time he purchases something). Because each customer is one physical person, you only need one record for the customer in the tblContacts table.

Each customer can make many purchases, however, which means you need to set up another table to hold information about each sale—thus, the tblSales table. Again, each invoice is one physical sale (on a specific day at a specific time). Each sale has one record in the tblSales table. Of course, you need to have some way to relate the buyer to the sales that the buyer makes in the tblSales table. This is accomplished by using a common field that is in both tables—in this case, the Buyer field in tblSales and ContactID in tblContacts (which has the identical type of information in both tables).

When linking tables, you link the primary key field from one table (the ContactID in the tblContacts table) to a foreign key field in the second table that has the same structure and type of data in it (the Buyer field in the tblSales table).

Besides being a common link field between tables, the primary key field in an Access database table has these advantages:

• Primary key fields are always indexed, greatly speeding up queries, searches, and sorts that involve the primary key field.

• Access forces you to enter a value (or automatically provides a value, in the case of AutoNumber fields) every time you add a record to the table. You’re guaranteed that your database tables conform to the rules of referential integrity.

• As you add new records to a table, Access checks for duplicate primary key values and prevents duplicates entries, thus maintaining data integrity.

• By default, Access displays your data in primary key order.

An index is a special internal file that is created to put the records in a table in some specific order. For instance, the primary key field in the tblContacts table is an index that puts the records in order by ContactID field. Using an indexed table, Access uses the index to quickly find records within the table.

Designating a primary key

From the preceding sections, you’re probably very well aware that choosing a table’s primary key is an important step towards bulletproofing a database’s design. When properly implemented, primary keys help stabilize and protect the data stored in your Access databases. As you read the following sections, keep in mind that the cardinal rule governing primary keys is that the values assigned to the primary key field within a table must be unique. Furthermore, the ideal primary key is stable.

Single field versus composite primary keys

Sometimes, when an ideal primary key does not exist within a table as a single value, you may be able to combine fields to create a composite primary key. For instance, it is unlikely that a first name or last name alone is enough to serve as a primary key, but by combining first and last names with birth dates, you may be able to come up with a unique combination of values to serve as the primary key. As you’ll see in the “Creating relationships and ensuring referential integrity” section, later in this chapter, Access makes it very easy to combine fields as composite primary keys.

The rules governing composite keys are quite simple:

• None of the fields in a composite key can be null.

• Sometimes composing a composite key from data naturally occurring within the table can be difficult. Sometimes records within a table differ by one or two fields, even when many other fields may be duplicated within the table.

• Each of the fields can be duplicated within the table, but the combination of composite key fields cannot be duplicated.

However, as with so many other issues in database design, composite keys carry a number of issues with them. First of all, composite keys tend to complicate a database’s design. If you use three fields in a parent table to define the table’s primary key, the same three fields must appear in every child table. Also, ensuring that a value exists for all of the fields within a composite key (so that none of the fields is null) can be quite challenging.

Most developers avoid composite keys unless absolutely necessary. In many cases, the problems associated with composite keys greatly outweigh the minimal advantage of using composite keys generated from data within the record.

Natural versus surrogate primary keys

Many developers maintain that you should only use natural primary keys. A natural key is derived from data already in the table, such as a Social Security number or employee number. If no single field is enough to uniquely identify records in the table, these developers suggest combining fields to form a composite primary key (we describe this process later in this section).

However, there are many situations where no “perfect” natural key exists in database tables. Although a field like SocialSecurityNumber may seem to be the ideal primary key, there are a number of problems with this type of data:

• The value is not universal. Not everyone has a Social Security number.

• The value may not be known at the time the record is added to the database. Because primary keys can never be null, provisions must be made to supply some kind of “temporary” primary key when the Social Security number is unknown, then other provisions must be made to fix up the data in the parent and child tables once the value becomes known.

• Values such as Social Security number tend to be rather large. A Social Security number is at least nine characters, even omitting the dashes between groups of numbers. Large primary keys unnecessarily complicate things and run more slowly than smaller primary key values.

By far the largest issue is that adding a record to a table is impossible unless the primary key value is known at the time the record is committed to the database. Even if temporary values are inserted until the permanent value is known, the amount of fix-up required in related tables can be considerable. After all, you can’t change the value of a primary key if related child records exist in other tables.

A majority of experienced Access developers have come to consistently use AutoNumber fields as the primary keys in their tables. Although an AutoNumber value does not naturally occur in the table’s data, because of the considerable advantages of using a simple numeric value that is automatically generated and cannot be deleted or changed, in most cases an AutoNumber is the ideal primary key candidate for most tables.

An artificially generated primary key is called a surrogate key. Historically, surrogate keys were only used as a last resort when no suitable natural key was available. Increasingly, however, surrogate keys are finding greater acceptance among database developers.

Creating primary keys

A primary key is created by opening a table in design view, selecting the field (or fields) that you want to use as a primary key, and clicking the Primary Key button on the toolbar (the button with the key on it). If you’re specifying more than one field to create a composite key, hold down the Ctrl key while using the mouse to select the fields before clicking on the Primary Key toolbar button.

If you choose to use a surrogate primary key, such as an AutoNumber field, add the field to the table, select it, and click the Primary Key button on the toolbar.

The primary key is created when you save the table after designating the table’s primary key. You’ll see an error message if Access detects a problem (such as null or duplicate values) during the save process. Of course, there will be no problems with the selected primary key if the table contains no records.

Creating relationships and enforcing referential integrity

The Relationships window Database Ribbon icon lets you specify the relationships and referential integrity rules you want to apply to the tables involved in a relationship. Creating a permanent, managed relationship that ensures referential integrity between Access tables is easy:

1. Choose Database Tools⇒Relationships.

The Relationships window appears.

2. Click on the Show Table button.

The Show Table dialog box (see Figure 3-15) appears.

Figure 3-15

Add the tables involved in a relationship in the Relationships window.

3. Drag the primary key field in the one-side table and drop it on the foreign key in the many-side table.

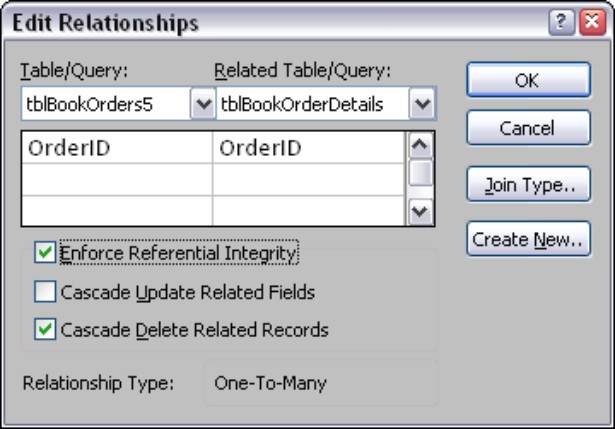

In Figure 3-15, you would drag the OrderID field from tblBookOrders5 and dropping it on OrderID in tblBookOrdersDetails. Access opens the Edit Relationships dialog box to enable you to specify the details about the relationship you intend to form between the tables. Notice that Access recognizes that the relationship between the tblBookOrders5 and tblOrderDetails is a one-to-many.

4. Specify the referential details you want Access to enforce in the database.

In Figure 3-16, Access ensures that deletions in the tblBooksOrders5 table are rippled to the tblOrderDetails table, deleting the corresponding records there.

Figure 3-16

You enforce referential integrity in the Edit Relationships dialog box.

In Figure 3-16 if the Cascade Delete Related Records check box were left unchecked, Access would not permit you to delete records in tblBookOrders5 until all of the corresponding records in tblOrderDetails were first manually deleted. With this box checked, deletions across the relationship are automatic.

5. Click the Create button.

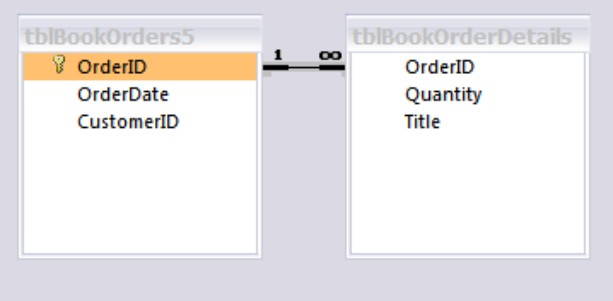

Access draws a line between the tables displayed in the Relationships window, indicating the type of relationship. In Figure 3-17, the 1 symbol indicates that tblBookOrders is the “one” side of the relationship while the infinity symbol designates tblOrderDetails as the “many” side.

Figure 3-17

A one-to-many relationship between tblBookOrders5 and tblBookOrderDetails.

Specifying the Join Type between tables

The right side of the Edit Relations window has four buttons: Create, Cancel, Join Type, and Create New. Clicking the Create button returns you to the Relationships window with the changes specified. The Cancel button cancels the current changes and returns you to the Relationships window. The Create New button lets you specify an entirely new relation between the two tables and fields.

By default, when you process a query on related tables, Access only returns records that appear in both tables. Considering the payroll example from the “Integrity Rules” section, earlier in this chapter, this means that you would only see employees that have valid paycheck records in the paycheck table. You would not see any employees who have not yet received a paycheck. Such a relationship is sometimes called an equi-join because the only records that appear are those that exist on both sides of the relationship.

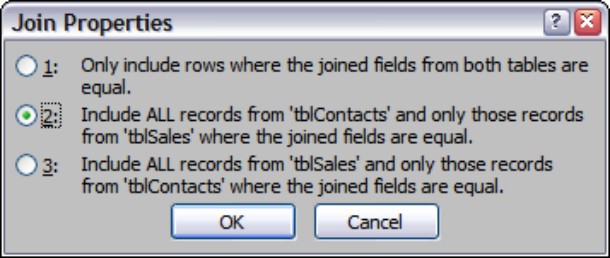

However, the equi-join is not the only type of join supported by Access. Click on the Join Type button to open the Join Properties dialog box. The alternative settings in the Join Properties dialog box allow you to specify that you prefer to see all of the records from either the parent table or child table, whether or not they are matched on the other side (it is possible to have an unmatched child record as long as the parent foreign key is null). Such a join (call an outer join) can be very useful because it accurately reflects the state of the data in the application.

In the case of the Access Auto Auction example, seeing all of the contacts, whether or not they have records in the Sales table, is what you’re shooting for. To specify an outer join connecting contacts to sales, perform these steps:

1. Click the Join Type button.

The Join Properties dialog box appears.

2. Click the Include ALL Records from ‘tblContacts’ and Only Those Records from ‘tblSales’ Where the Joined Fields Are Equal check box.

The relationship between these tables should now look like what you see in Figure 3-18.

3. Click OK.

You’re returned to the Edit Relationships dialog box.

4. Click OK.

You’re returned to the Relationships window. The Relationships window should now show an arrow going from the Contacts table to the Sales table. At this point, you’re ready to set referential integrity between the two tables.

Figure 3-18

The Join Properties dialog box, used to set up the join properties between the Contacts and Sales tables. Notice that it specifies all records from the Contacts table.

Establishing a join type for every relationship in your database is not absolutely necessary. In the following chapters, you’ll see that you can specify outer joins for each query in your application. Many developers choose to use the default equi-join for all the relationships in their databases, and to adjust the join properties on each query to yield the desired results.

Enforcing referential integrity

After using the Edit Relationships dialog box to specify the relationship, verify the table and related fields, and specify the type of join between the tables, you should set referential integrity between the tables. Select the Enforce Referential Integrity check box in the lower portion of the Edit Relationships dialog box to indicate that you want Access to enforce the referential integrity rules on the relationship between the tables.

If you choose not to enforce referential integrity, you can add new records, change key fields, or delete related records without warnings about referential integrity violations—thus making it possible to change critical fields and damaging the application’s data. With no integrity active, you can create tables that have orphans (Sales without a Contact). With normal operations (such as data entry or changing information), referential integrity rules should be enforced.

Enforcing referential integrity also enables two other options (cascading updates and cascading deletes) that you may find useful. These options can be checked in the Edit Relationships dialog box, as shown in Figure 3-19.

Figure 3-19

Referential Integrity set between the tblSales and tblContacts tables

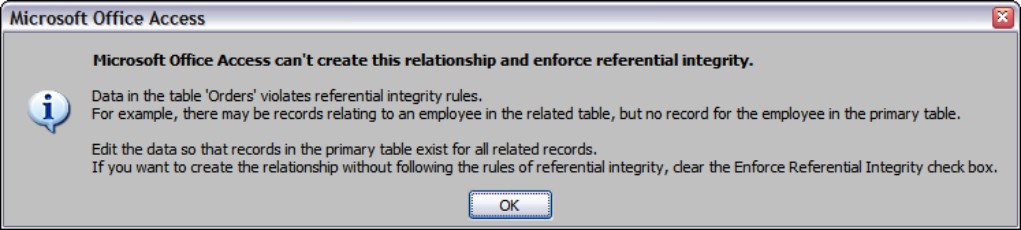

You might find, when you specify Enforce Referential Integrity and click the Create button (or the OK button if you’ve reopened the Edit Relationships window to edit a relationship), that Access will not allow you to create a relationship and enforce referential integrity. The most likely reason for this behavior is that you’re asking Access to create a relationship that violates referential integrity rules, such as a child table with orphans in it. In such a case, Access warns you by displaying a dialog box similar to that shown in Figure 3-20. The warning happens in this example because there are some records in the Sales table with no matching value in the Salesperson table. This means that Access cannot enforce referential integrity between these tables because the data within the tables already violate the rules.

Figure 3-20

A dialog box warning that referential integrity cannot be created between two tables due to integrity violations

To solve any conflicts between existing tables, you can create a Find Unmatched query by using the Query Wizard to find the records in the many-side table that violate referential integrity. Then you can convert the Unmatched query to a Delete query to delete the offending records or add the appropriate value to the SalespersonID field.

You could remove the offending records and return to the Relationships window and set referential integrity between the two tables. However, you should not do this, because Salesperson is not a critical field that requires referential integrity to be set between these tables.

Choosing the Cascade Update Related Fields option

If you specify Enforce Referential Integrity in the Edit Relationships dialog box, Access enables the Cascade Update Related Fields check box. This option tells Access that, as a user changes the contents of a related field (the primary key field in the primary table—ContactID, for example), the new ContactID is rippled through all related tables.

If this option is not selected, you cannot change the primary key value in the primary table that is used in a relationship with another table.

If the primary key field in the primary table is a related field between several tables, this option must be selected for all related tables or it won’t work.

Generally speaking, however, there are very few reasons why the value of a primary key may change. The example we give in the “Connecting the Data” section, earlier in this chapter, of a missing Social Security number is one case where you may need to replace a temporary Social Security number with the permanent Social Security number after employee data have been added to the database. However, when using AutoNumbers or other surrogate key values, there is seldom any reason to have to change the primary key value once a record has been added to the database.

Choosing the Cascade Delete Related Records option

The Cascade Delete Related Records option instructs Access to delete all related child records when a parent record is deleted. Although there are instances where this option can be quite useful, as with so many other options, cascading deletes come with a number of warnings.

For example, if you have chosen Cascade Delete Related Records and you try to delete a particular customer (who moved away from the area), Access first deletes all the related records from the child tables—Sales and SalesLineItems—and then deletes the customer record. In other words, Access deletes all the records in the sales line items for each sale for each customer—the detail items of the sales, the associated sales records, and the customer record—with one step.

Perhaps you can already see the primary issue associated with cascading deletes. If all of a customer’s sales records are deleted when the customer record is deleted, you have no way of properly reporting historic financial data. You could not, for instance, reliably report on the previous year’s sales figures because all of the sales records for “retired” customers have been deleted from the database. Also, in this particular example, you would lose the opportunity to report on sales trends, product category sales, and a wide variety of other uses of the application’s data.

To use this option, you must specify Cascade Delete Related Records for all of the table’s relationships in the database. If you do not specify this option for all the tables in the chain of related tables, Access will not allow cascade deleting.

Viewing all relationships

With the Relationships dialog box open, Choose View⇒All Relationships to see all of the relationships in the database. If you want to simplify the view you see in the Relationships window, you can “hide” a relationship by deleting the tables you see in the Relationships window. Click on a table, press the Delete key, and Access removes the table from the Relationships window. Removing a table from the Relationships window does not delete any relationships between the table and other tables in the database.

Make sure that the Required property of the foreign key field in the related table (in the case of tblBookOrders5 and tblBookOrderDetails, the foreign key is OrderID in tblBookOrderDetails) is set to Yes. This ensures that the user enters a value in the foreign key field, providing the relationship path between the tables.

The relationships formed in the Relationships window are permanent and are managed by Access. When you form permanent relationships, they appear in the Query Design window by default as you add the tables (queries are discussed in detail in Chapters 3 and 4). Even without permanent relationships between tables, you form temporary relationships any time you include multiple tables in the Query Design window.

If you connect to a SQL Server back-end database or use the Microsoft Database Engine and create an Access Data Project, the Relationships window is different. You can find more about this subject in Chapter 28.

Deleting relationships