Cognitive Psychology: Memory, Language, and Problem-Solving

According to the modal model, memory is divided into three separate storage areas: sensory, short-term, and long-term. Each type of memory has four components: storage capacity, duration of code, nature of code, and a way by which information is lost. Consider each type of memory in turn.

Sensory memory is the gateway between perception and memory. This store is quite limited. Information in sensory memory is referred to as iconic if it is visual and echoic if it is auditory. The iconic store lasts for only a few tenths of a second while the echoic store lasts for three or four seconds. The items in sensory memory are constantly being replaced by new input, with only certain items entering into short-term memory.

The nature of sensory memory is clarified by certain types of events. If you have ever watched someone jump rope quickly, you may have noticed the perception of the rope being at many points in its rotation at once. A quickly moving fan also may generate such a perception. This phenomenon is called visual persistence. Sensory information in sensory memory remains in attention briefly; the speed of the rope or fan causes the sensory information to run together.

In 1960, researcher George Sperling experimented on memory and partial report. He first presented participants with a matrix of three rows of four letters each for just milliseconds.

Next, he asked participants to either recite the entire matrix or to recollect just one of the rows. He found that while participants were not able to recall all twelve letters presented due to the rapid decay of iconic memory, they were generally able to accurately recall the cued row, meaning they had an image of the entire matrix stored in memory. Sperling called this ability to recall these lines of letters iconic memory or short-term visual memory. This suggests that the capacity for iconic memory is quite large, but the duration is incredibly short, and the information is not easily manipulable. Additionally, further studies emphasized the brief window for retention—the longer the amount of time between seeing the matrix and being cued to recall the row, the worse the participants performed.

Short-term memory holds information from a few seconds up to about a minute. Psychologist George Miller found that the information stored in this portion of memory is primarily acoustically coded, despite the nature of the original source. Short-term memory can hold about seven items, plus or minus two (convenient for telephone numbers). Items in the short-term store are maintained there by rehearsal. Rehearsal can be divided into two types: maintenance rehearsal and elaborative rehearsal. Maintenance rehearsal is simple repetition to keep an item in short-term memory until it can be used (as when you say a phone number to yourself over and over again until you can dial it). Elaborative rehearsal involves organization and understanding of the information that has been encoded in order to transfer the information to long-term memory (as when you try to remember the name of someone you have just met at a party). Elaborative rehearsal is more effective than maintenance rehearsal for ensuring short-term memory information is sent to long-term memory; therefore, it is a preferred way to study.

There is some evidence that the depth of processing is important for encoding memories. Information that is thought about at a deeper level is better remembered. For example, it is easier to remember the general plot of a book than the exact words, meaning that semantic information (meaning) is more easily remembered than grammatical information (form) when the goal is to learn a concept. On the other hand, rhyme can be useful in aiding phonological processing. Another useful mnemonic device is to use short words or phrases that represent longer strings of information. For example, ROYGBIV is an acronym that is helpful in memorizing the colors of the rainbow (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). A mnemonic device is any technique that makes it easier to learn and remember something.

The dual-coding hypothesis indicates that it is easier to remember words with associated images than either words or images alone. By encoding both a visual mental representation and an associated word, there are more connections made to the memory and more of an opportunity to process the information at a deeper level. For this reason, imagery is a useful mnemonic device. One aid for memory is to use the method of loci. This involves imagining moving through a familiar place, such as your home, and in each place, leaving a visual representation of a topic to be remembered. For recall, then, the images of the places could be called upon to bring into awareness the associated topics.

It is also easier to remember things that are personally relevant, known as the self-reference effect. We have excellent recall for information that we can personally relate to because it interacts with our own views or can be linked to existing memories. A useful tool for memory, then, is to relate new information to existing knowledge by making it personally relevant.

Items in short-term memory may be forgotten or they may be encoded (stored and able to be recalled later) into long-term memory. Items that are forgotten exit short-term memory either by decay—that is, the passage of time—or by interference—that is, they are displaced by new information. One type of interference is retroactive interference, in which new information pushes old information out of short-term memory. The opposite of retroactive interference is proactive interference, in which old information makes it more difficult to learn new information.

An additional feature of short-term memory is that it seems to store items from a list sequentially. This sequential storage leads to our tendency to remember the first few and last few items in a list better than the ones in the middle. These effects are called the primacy (remembering the first items) and recency (remembering the last items) effects. The recency effect tends to fade in about a day; the primacy effect tends to persist longer. The overall effect is called the serial position effect.

An interesting feature of short-term memory is that its limit of about seven items is not as limiting as it would seem. The reason is that what constitutes an item need not be something as simple as a single digit. In fact, it can be a fairly large block of information. George Miller defined grouping items of information into units as chunking. For example, when learning a friend’s phone number (typically seven digits), you probably chunk the information into a 3-digit and a 4-digit number in order to better retain the information.

Long-term memory is the repository for all of our lasting memories and knowledge, and it is organized like a gigantic network of interrelated information. It is capable of permanent retention for the duration of our lives. Evidence suggests that information in this store is primarily semantically encoded—that is, encoded in the form of word meanings. However, certain types of information in this store can be either visually encoded or acoustically encoded.

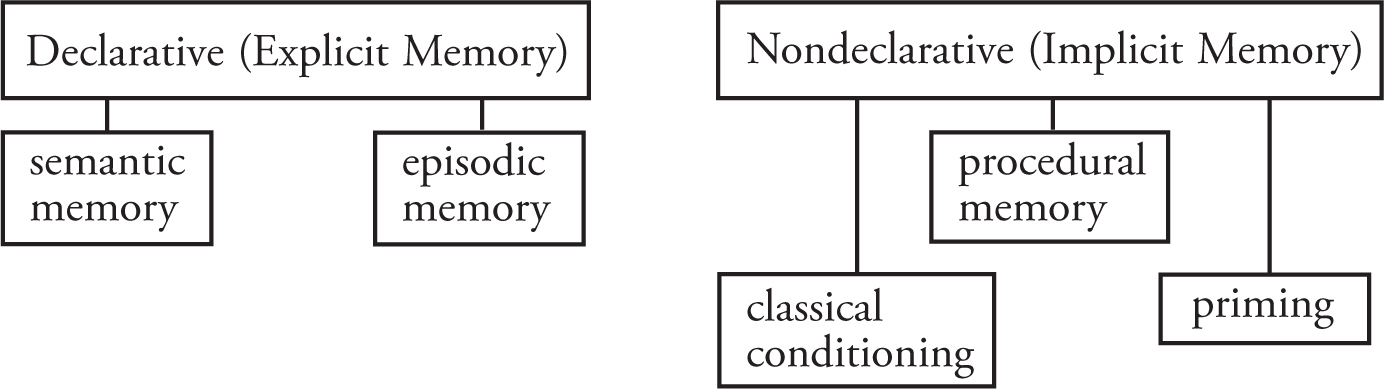

Information in the long-term store can be stored in different ways, depending on the type of information it is. One kind of storage is through episodic memory, or memory for events that we ourselves have experienced. Another kind is through semantic memory, also known as declarative, which comprises facts, figures, and general world knowledge. A third type is procedural memory—that is, consisting of skills and habits. Because these memories are stored in the striatum, they are frequently not subject to damage and injury. A final way to classify memory is into categories based on whether or not it can be accessed consciously or not. Declarative (or explicit) memory is a memory a person can consciously consider and retrieve, such as episodic and semantic memory. In contrast, nondeclarative (or implicit) memory is beyond conscious consideration and would include procedural memory, priming, and classical conditioning.

Recalling items in long-term memory is subject to context-dependent memory. This principle states that information is more likely to be recalled if the attempt to retrieve it occurs in a situation similar to the situation in which it was encoded. For example, if you memorize information about psychology while in a classroom, you should remember it better in that same classroom than if the information was memorized at home. State-dependent memory also applies to states of mind, meaning that information memorized when under the influence of a drug is easier to access when in a similar state than when not on that drug.

Some psychologists believe there is an additional type of memory called working memory. Within the modal model, it is argued that working memory would fall between the sensory registry and short-term memory, and it can last up to about 30 seconds before decaying or being transferred into either short- or long-term memory. It is believed that the information stored in working memory can be manipulated in a way that iconic or echoic memory would not be, which helps distinguish working memory from other more evanescent forms of memory. For example, iconic memory would allow a person to remember five letters presented visually, whereas working memory would allow a person to remember those five letters and rearrange them in alphabetical order. While some psychologists are certain that working memory is a distinct part of the memory system, other psychologists believe that working memory is simply a part of short-term memory.

The process of retrieval is thought to involve the activation of semantic networks. If our long-term memories contained isolated pockets of information without any organization, they might be more difficult to access. A person might have numerous memories for directions, people’s faces, the definitions of tens of thousands of words, and other such content; with that much information, it could be nearly impossible to find anything. Just as hierarchies are useful for handling information during the encoding process, it is believed that information is stored in long-term memory as an organized network. In this network exist individual ideas called nodes, which can be thought of like cities on a map. Connecting these nodes are associations, which are like roads connecting the cities. Not all roads are created equal; some are superhighways while others are dirt roads. For example, for a person living in a city, there may be a stronger association between the nodes “bird” and “pigeon” than between “bird” and “penguin.” According to this model, the strength of an association in the network is related to how frequently and how deeply the connection is made. Processing material in different ways leads to the establishment of multiple connections. In this model, searching through memory is the process of starting at one node and traveling the connected roads until one arrives at the idea one is looking for. Retrieval of information can be improved by building more and stronger connections to an idea. Because all memories are, in essence, neural connections, the road analogy provides a useful visual aid in understanding access to memories: strong neural connections are like better roads.

Like any neural connection, a node does not become activated until it receives input signals from its neighbors that are strong enough to reach a response threshold. The effect of input signals is cumulative: the response threshold is reached by the summation of input signals from multiple nodes. Stronger memories involve more neural connections in the form of more numerous dendrites, the stimulation of which can summate more quickly and powerfully to threshold. Once the response threshold is reached, the node “fires” and sends a stimulus to all of its neighbors, contributing to their activation. In this way, the activation of a few nodes can lead to a pattern of activation within the network that spreads onward. This process is known as spreading activation. It suggests that when trying to retrieve information, we start the search from one node. We do not then “choose” where to go next; rather, that activated node spreads its activation to other nodes around it to an extent related to the strength of association between that node and each other. This pattern continues, with well-established links carrying activation more efficiently than more obscure ones. The network approach helps explain why hints may be helpful. They serve to activate nodes that are closely connected to the node being sought after, which may therefore contribute to that node’s activation. It also explains the relevance of contextual cues in state-dependent memory.

A phenomenon that many psychologists believe occurs in the long-term store is the flashbulb memory, which is a very deep, vivid memory in the form of a visual image associated with a particular emotionally arousing event. For example, many people remember exactly what they were doing when they heard that planes had crashed into the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. However, some psychologists believe that recall of such events is no more accurate than recall of other memories.

Sometimes what we remember happened only in part or even not at all. Memory reconstruction occurs when we fit together pieces of an event that seem likely. Source confusion is one likely cause of memory reconstruction. In this case, we attribute the event to a different source than it actually came from. For example, if children read and reread a story, they may come to think the events of the story happened to them rather than to the character. Similarly, childhood memories of both trivial and serious events can be reconstructed (falsified) by repeated suggestion. Elizabeth Loftus and other psychologists are studying the existence of false or implanted memories. They have demonstrated that repeated suggestions and misleading questions can create false memories. This is called framing. Similarly, eyewitness accounts, thought to be very strong evidence in courts of law, are accurate only about half the time. This is particularly true when dealing with children as eyewitnesses. The degree of confidence in the testimony of the witness does not necessarily correlate to accuracy of the account.

Before we move on, let’s mention types of interference that we discussed briefly in the short-term memory section. Retroactive interference occurs when newly memorized information interferes with the ability to remember previously memorized information. Proactive interference occurs when previously memorized information interferes with the ability to learn and memorize new information. To give an example of retroactive interference, when you learn a new language (such as Spanish), it can interfere with your memory of a language that you learned previously (for example, Italian).

Language is the arrangement of sounds, written symbols, or gestures to communicate ideas. Language has several key features.

First, language is arbitrary—that is, words rarely sound like the ideas that they convey.

Second, language has a structure that is additive in a certain sense. For example, words are added together to form sentences, sentences to form paragraphs, and so on.

Third, language has multiplicity of structure, meaning that it can be analyzed and understood in a number of different ways.

Fourth, language is productive, meaning that there are nearly endless meaningful combinations of words.

Finally, language is dynamic, meaning that it is constantly changing and evolving.

Language can be broken down into subcomponents. Phonemes are the smallest units of speech sounds in a given language that are still distinct in sound from each other. Phonemes combine to form morphemes, the smallest semantically meaningful parts of language. Grammar, the set of rules by which language is constructed, is governed by syntax and semantics. Syntax is the set of rules used in the arrangement of morphemes into meaningful sentences; this can also be thought of as word order. Semantics refers to word meaning or word choice. Prosody is the rhythm, stress, and intonation of speech.

Children acquire language in stages. Infants make cooing noises, which consist of the utterance of phonemes that do not correspond to actual words, until roughly 4 months of age. The next stage after cooing is babbling, which is the production of phonemes only within the infants’ own to-be-learned language. Sounds not relevant to this language drop out at this stage, which usually lasts until the first year of life. Soon the infant uses single words to convey demands and desires. These single words filled with meaning are called holophrases. Holophrases are single terms that are applied by the infant to broad categories of things. For example, it is not uncommon to hear an infant call any passing woman “mama.” This type of error is known as an overextension, and it results from the infant not knowing enough words to express something fully. Underextension is when a child thinks that his or her “mama” is the only “mama.” Infants develop vocabulary as time goes on and tend to have up to 100 words in their vocabulary by 18 months.

At about two years of age, infants start combining words. Two- or three-word groups are termed telegraphic speech. This speech lacks many parts of speech. For example, a two-year-old would say, “mommy food,” which means “mommy, give me food.” This is called “telegraphic speech” because people used to remove what they deemed unnecessary words when sending telegrams, in order to save money.

Vocabulary is increasing rapidly at this point. By age 3, children know more than 1,000 words, but they frequently make overgeneralization errors. These are errors in which the rules of language are overextended, such as in saying, “I goed to the store.” Go is an irregular verb, but the child applies the standard rules of grammar to it. By age 5, most grammatical mistakes in the child’s speech have disappeared, and the child’s vocabulary has expanded dramatically. At 10 years old, a child’s language is essentially the same as an adult’s.

Noam Chomsky postulated a system for the organization of language based on the concept of what he referred to as transformational grammar. Transformational grammar differentiates between the surface structure of language—the superficial way in which the words are arranged in a text or in speech—and the deep structure of language—the underlying meaning of the words. Chomsky was struck by the similarities between the grammars of different languages, as well as by the similarities of language acquisition in children, regardless of the language they were learning. Based on this similarity, he proposed an innate language acquisition device, which facilitates the acquisition of language in children, and a critical period for the learning of language. B.F. Skinner, a noted behaviorist, countered Chomsky’s argument for language acquisition. Skinner explored the idea of the “language acquisition support system,” which is the language-rich or language-poor environment the child is exposed to while growing up. Chomsky’s language acquisition device (LAD) provides the foundational structure of language, while the language acquisition support system (LASS) provides the scaffolding to help young children learn language.

Language and thought are interactive processes. Language can influence thought, and cognition can influence language. Benjamin Lee Whorf, in collaboration with Edward Sapir, proposed a theory of linguistic relativity, according to which speakers of different languages develop different cognitive systems as a result of their differences in language. A popularly cited example of this idea is illustrated by the Garo people of Burma, who have many words for rice. English speakers have only a few words to describe rice. The hypothesis is that rice is critical to the Garo way of life and so involves more categorization and complexity of thought than it does for someone in an English-speaking culture.

We are constantly being inundated with information about our surroundings. In order to organize all of this information, we devise concepts. A concept is a way of grouping or classifying the world around us. For example, chairs come in a large variety of sizes and shapes, yet we can identify them as chairs. The concept of chairs allows us to identify them without learning every possible trait of all chairs. Typicality is the degree to which an object fits the average. What are the average characteristics of a chair? When we picture “chair,” an image emerges in our brain. This typical picture that we envision is referred to as a prototype. But we can imagine other images of a chair that are distant from the prototype to varying degrees.

Concepts can be small or large, more or less inclusive. A superordinate concept is very broad and encompasses a large group of items, such as the concept of “food.” A basic concept is smaller and more specific—for example, “bread.” A subordinate concept is even smaller and more specific, such as “rye bread.” Concepts are essential for thinking and reasoning. Without such categorization, we would be so overwhelmed by our surroundings that we would be incapable of any deeper thought.

Cognition encompasses the mental processes involved in acquiring, organizing, remembering, using, and constructing knowledge.

Reasoning, the drawing of conclusions from evidence, can be further divided into deductive and inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is the process of drawing logical conclusions from general statements. Syllogisms are deductive conclusions drawn from two premises. For example, consider the following argument:

All politicians are trustworthy.

Janet is a politician.

Therefore, Janet is trustworthy.

The logical conclusion is that Janet is trustworthy. This is drawn from the general statements that all politicians are trustworthy and that Janet is a politician. In general, statements can be sound (the conclusion follows from the premises), unsound, valid (the conclusion is true—Janet is trustworthy), or invalid.

Inductive reasoning is the process of drawing general inferences from specific observations. For example, you might notice that everybody on the football team seems to be a good student. You could infer that all people who play football are good students. However, this is not necessarily true. You are drawing an inference based on a common occurrence. Inductive reasoning, while useful, is not as airtight as deductive reasoning.

Problem-solving involves the removal of one or more impediments to the finding of a solution in a situation. The problems to be solved can be either well-structured, with paths to solution (for example, “What is the square footage of my room?”), or ill-structured, with no single, clear path to solution (for example, “How can I succeed in school?”). In order to solve problems, we must decide whether the problem has one or more solutions. If many correct answers are possible, we use a process known as divergent thinking. Brainstorming is an example of divergent thinking. If the problem can be solved only by one answer, convergent thinking must be used. Convergent thinking, then, requires narrowing of the many choices available.

When solving well-structured problems, we often rely on heuristics, or intuitive rules of thumb that may or may not be useful in a given situation. There are a number of types of heuristics and all may lead to incorrect conclusions. The availability heuristic means that the rule of thumb is judged by what events come readily to mind. For example, many people mistakenly believe that air travel is more dangerous than car travel because airplane crashes are so vividly and repeatedly reported. The representativeness heuristic also can lead to incorrect conclusions. In this case, we judge objects and events in terms of how closely they match the prototype of that object or event. For example, many people view high school athletes as less intelligent. However, most high school athletes must meet certain academic standards in order to participate in sports. A person’s particular view of the athlete will determine whether the representativeness heuristic is leading to a correct or incorrect conclusion. Unfortunately, such erroneous conclusions are how racism, sexism, and ageism persist. Heuristics contrast with algorithms, which are systematic, mechanical approaches that guarantee an eventual answer to a problem.

Ill-structured problems often require insight to be solved. Insight is the sudden understanding of a problem or a potential strategy for solving a problem that usually involves conceptualizing the problem in a new way. Recent studies have demonstrated that insight is more likely to occur when the problem-solvers are able to create some mental and/or physical space between themselves and the problem.

A famous example of insight is the example of Köhler’s chimps. Wolfgang Köhler had a chimp in a cage with two sticks. Outside of the cage were some bananas. The chimp wanted the bananas but could not reach them with either stick. After struggling for a while, the chimp took the two sticks, and put the thinner end of one into the hollow end of the other, making one long stick of sufficient length to reach the bananas. The novel approach of combining the sticks was presumably the result of an insight.

Problems requiring insight are often difficult to solve because we have a mental set, or fixed frame of mind, that we use when approaching the problems. An example of a mental set is functional fixedness, which is the tendency to assume that a given item is useful only for the task for which it was designed. For example, many people might see this AP Psychology book as a source of information for the AP Exam, but it can also serve as a bed support, a writing surface, a source of kindling, or much more!

Other obstacles to problem-solving include confirmation bias, hindsight bias, belief perseverance, and framing. Confirmation bias, the search for information that supports a particular view, also hinders problem-solving by distorting objectivity. The hindsight bias, or the tendency after the fact to think you knew what the outcome would be, also distorts our ability to view situations objectively. Similarly, belief perseverance affects problem-solving. In this mental error, a person sees only the evidence that supports a particular position, despite evidence presented to the contrary. Framing, or the way a question is phrased, can alter the objective outcome of problem-solving or decision-making.

Creativity can be defined as the process of producing something novel yet worthwhile. The elusive nature of creativity makes it a difficult topic to study. For example, what is truly novel, and who is the judge of what is or is not worthwhile? Briefly, creative people tend to be motivated to create, primarily for the sheer joy of creation, rather than for financial or material gain. Creative people also seem to exhibit care and consideration when choosing a specific area of interest to pursue. Once they have chosen that area, they tend to immerse themselves in it and to develop extensive knowledge of all aspects of the topic. Creativity seems to correlate with nonconformity to the rules governing the area of creativity. For example, Copernicus had to disregard the common belief that the Earth was the center of the solar system to make his discoveries about planetary motion.

Memory

modal model

sensory memory

short-term memory

long-term memory

iconic

echoic

visual persistence

George Sperling

partial report

short-term visual memory (iconic memory)

George Miller

maintenance rehearsal

elaborative rehearsal

mnemonic device

dual-coding hypothesis

method of loci

self-reference effect

encoded

decay

interference

retroactive interference

proactive interference

primacy effect

recency effect

serial position effect

chunking

semantically encoded

visually encoded

acoustically encoded

episodic memory

semantic memory

procedural memory

declarative (or explicit) memory

nondeclarative (or implicit) memory

context-dependent memory

state-dependent memory

working memory

spreading activation

flashbulb memory

reconstruction

source confusion

framing

Elizabeth Loftus

Language

phoneme

morpheme

grammar

syntax

semantics

prosody

holophrases

overextension

underextension

telegraphic speech

overgeneralization

Noam Chomsky

transformational grammar

surface structure of language

deep structure of language

language acquisition device

critical period

B.F. Skinner

Benjamin Lee Whorf

Edward Sapir

theory of linguistic relativity

Concepts

concept

typicality

prototype

superordinate concept

basic concept

subordinate concept

Cognition

cognition

reasoning

deductive reasoning

syllogisms

inductive reasoning

Problem-Solving and Creativity

divergent thinking

convergent thinking

heuristics

availability heuristic

representativeness heuristic

algorithms

insight

Wolfgang Köhler

mental set

functional fixedness

confirmation bias

hindsight bias

belief perseverance

framing

creativity

See Chapter 19 for answers and explanations.

1. The main difference between auditory and visual sensory memory is that

(A) visual memory dominates auditory memory

(B) visual sensory memory lasts for a shorter period of time than auditory sensory memory

(C) visual sensory memory has a higher storage capacity than auditory sensory memory

(D) a phone number read to an individual will be lost before a phone number that was glanced at for 15 seconds

(E) if both visual and auditory stimuli are presented at the same time, the visual stimulus is more likely to be transferred to the long-term memory than is the auditory stimulus

2. The greater likelihood of recalling information from memory while in the same or similar environment in which the memory was originally encoded is an example of

(A) retroactive interference

(B) chunking

(C) elaborative rehearsal

(D) context-dependent memory

(E) procedural memory

3. The term given to that part of language composed of tones and inflections that add or change meaning without alterations in word usage is

(A) syntax

(B) grammar

(C) phonemics

(D) semantics

(E) prosody

4. Which of the following would NOT be an example of a two-year-old’s usage of telegraphic speech?

(A) “Where ball?”

(B) “Boy hurt.”

(C) “Milk.”

(D) “Mommy give hug.”

(E) “Go play group.”

5. Students are given a reasoning task in which they are asked, in 60 seconds, to come up with as many ways as possible to use a spoon that do not involve eating or preparing food. The number and diversity of responses could most accurately reflect the students’

(A) divergent thinking abilities

(B) convergent thinking abilities

(C) intelligence quotients

(D) working memories

(E) subordinate concepts

6. Recalling the fact that Abraham Lincoln was the president of the United States during the Civil War is an example of

(A) procedural memory

(B) implicit memory

(C) semantic memory

(D) episodic memory

(E) nondeclarative memory

7. Stefano tries his hardest to learn German, but he continues to replace words with Spanish words by accident. This is most likely a result of

(A) proactive interference

(B) retroactive interference

(C) telegraphic speech

(D) surface structure of language

(E) semantic encoding

8. Ben continues to get stuck on a physics problem, approaching it the same way every time. This is an example of

(A) functional fixedness

(B) a mental set

(C) a representativeness heuristic

(D) insight learning

(E) framing

9. Which of the following is an example of a representativeness heuristic?

(A) Kelly creates a perfect mental image of a rose in her mind.

(B) Malik thinks that cancer is more deadly than heart disease because he sees advertisements for cancer research frequently.

(C) Priscilla uses a box as a stepstool to reach the highest shelf.

(D) In an effort to prove her theory true, Jennifer interprets the otherwise objective facts as supporting evidence for her claims.

(E) Looking back, Justino feels he should have been able to predict the ending of the horror movie all along.

10. Sheldon memorizes organic chemistry functional groups by relating them to his passion and understanding of landscaping. This memorization technique is known as

(A) functional fixedness

(B) chunking

(C) maintenance rehearsal

(D) state-dependent memory

(E) self-referential effect

Respond to the following questions:

Which topics in this chapter do you hope to see on the multiple-choice section or essay?

Which topics in this chapter do you hope not to see on the multiple-choice section or essay?

Regarding any psychologists mentioned, can you pair the psychologists with their contributions to the field? Did they contribute significant experiments, theories, or both?

Regarding any theories mentioned, can you distinguish between differing theories well enough to recognize them on the multiple-choice section? Can you distinguish them well enough to write a fluent essay on them?

Regarding any figures given, if you were given a labeled figure from within this chapter, would you be able to give the significance of each part of the figure?

Can you define the key terms at the end of the chapter?

Which parts of the chapter will you review?

Will you seek further help, outside of this book (such as a teacher, Princeton Review tutor, or AP Students), on any of the content in this chapter—and, if so, on what content?