Motivation and Emotion

Motivation is defined as a need or desire that serves to energize or direct behavior.

Learning is motivated by biological and physiological factors. Without motivation, action and learning do not occur. Animals are motivated to act by basic needs critical to the survival of the organism. For a given organism to survive, it needs food, water, and sleep. For the genes of the organism to replicate, reproductive behavior is needed to produce offspring and to foster their survival. Hunger, thirst, sleep, and reproduction needs are primary drives. The desire to obtain learned reinforcers, such as money or social acceptance, is a secondary drive.

The interaction between the brain and motivation was noticed when Olds and Milner discovered that rats would press a bar in order to send a small electrical pulse into certain areas of their brains. This phenomenon is known as intracranial self-stimulation. Further research demonstrated that if the electrode was implanted into certain parts of the limbic system, the rat would self-stimulate nearly constantly. The rats were motivated to stimulate themselves. This finding also suggests that the limbic system, particularly the nucleus accumbens, must play a pivotal role in motivated behavior, and that dopamine, which is the prominent neurotransmitter in this region, must be associated with reward-seeking behavior.

Four primary theories attempt to explain the link between neurophysiology and motivated behavior: instinct theory, arousal theory, opponent process theory, and drive-reduction theory.

Instinct theory, supported by evolutionary psychology, posits that the learning of species-specific behavior motivates organisms to do what is necessary to ensure their survival. For example, cats and other predatory animals have an instinctive motivation to react to movement in their environment to protect themselves and their offspring.

Arousal theory states that the main reason people are motivated to perform any action is to maintain an ideal level of physiological arousal. Arousal is a direct correlate of nervous system activity. A moderate arousal level seems optimal for most tasks, but keep in mind that what is optimal varies by person as well as task. The Yerkes-Dodson law states that tasks of moderate difficulty, neither too easy nor too hard, elicit the highest level of performance. The Yerkes-Dodson law also posits that high levels of arousal for difficult tasks and low levels of arousal for easy tasks are detrimental, while high levels of arousal for easy tasks and low levels of arousal for difficult tasks are preferred.

The opponent process theory is a theory of motivation that is clearly relevant to the concept of addiction. It posits that we start off at a motivational baseline, at which we are not motivated to act. Then we encounter a stimulus that feels good, such as a drug or even a positive social interaction. The pleasurable feelings we experience are the result of neuronal activity in the pleasure centers of the brain (the nucleus accumbens). We now have acquired a motivation to seek out the stimulus that made us feel good. Our brains, however, tend to revert back to a state of emotional neutrality over time. This reversion is a result of an opponent process, which works in opposition to the initial motivation toward seeking the stimulus. In other words, we are motivated to seek stimuli that make us feel emotion, after which an opposing motivational force brings us back in the direction of a baseline. After repeated exposure to a stimulus, its emotional effects begin to wear off; that is, we begin to habituate to the stimulus. The opponent process, however, does not habituate as quickly, so what used to cause a very positive response now barely produces one at all. Additionally, the opponent process overcompensates, producing withdrawal. As with drugs, we now need larger amounts of the formerly positive stimuli just to maintain a baseline state. In other words, we are addicted.

The drive-reduction theory of motivation posits that psychological needs put stress on the body and that we are motivated to reduce this negative experience. Another way to view motivation is using the homeostatic regulation theory, or homeostasis. Homeostasis is a state of regulatory equilibrium. When the balance of that equilibrium shifts, we are motivated to try to right the balance. A key concept in the operation of homeostasis is the negative feedback loop. When we are running out of something, like fuel, a metabolic signal is generated that tells us to eat food. When our nutrient supply is replenished, a signal is issued to stop eating. The common analogy for this process is a home thermostat in a heating-cooling system. It has a target temperature, called the set point. The job of the thermostat is to maintain the set point. If body weight rises above the set point, the action of the ventromedial hypothalamus will send messages to the brain to eat less and to exercise more. Conversely, when body weight falls below the set point, the brain sends messages to eat more and exercise less through the lateral hypothalamus.

The homeostatic regulation model provides a biological explanation for the efficacy of primary reinforcers such as hunger and sex. The brain provides a large amount of the control over feeding behavior. Specifically, the hypothalamus has been identified as an area controlling feeding. This control can be demonstrated by lesion studies in animals. If the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) is lesioned, the animal eats constantly. The negative feedback loop that should turn off eating has been disrupted. If we damage a neighboring portion of the hypothalamus, the lateral hypothalamus (LH), then the animal stops eating, often starving to death. In more normal circumstances, leptin plays a role in the feedback loop between signals from the hypothalamus and those from the stomach. Leptin is released in response to a buildup of fat cells when enough energy has been consumed. This signal is then interpreted by the satiety center in the hypothalamus, working as a safety valve to decrease the feeling of hunger.

The feedback loop that controls eating can be broken by damaging the hypothalamus, but the operation of this mechanism raises the question of what is actually monitored and regulated in normal feeding behavior. Two prime candidates exist. The first candidate hypothesis is blood glucose. This idea forms the basis for the glucostatic hypothesis. Glucose is the primary fuel of the brain and most other organs. When insulin (a hormone produced by the pancreas to regulate glucose) rises, glucose decreases. To restore glucostatic balance, a person needs to eat something. If cellular fuel gets low, then it needs to be replenished. The glucostatic theory of energy regulation gains support from the finding that the hypothalamus has cells that detect glucose.

The glucostatic theory is not without flaws, however. Blood glucose levels are very transient, rising and falling quite dramatically for a variety of reasons. How could it be, then, that such a variable measure could control body weight, which remains relatively stable from early adulthood onward? Another phenomenon inconsistent with a glucostatic hypothesis is diabetes, a disorder of insulin production. Diabetics have greatly elevated blood glucose, but they are no less hungry than everyone else.

A second candidate hypothesis is called the lipostatic hypothesis. As you might have guessed, this theory states that fat is the measured and controlled substance in the body that regulates hunger. Fat provides the long-term energy store for our bodies. The fat stores in our bodies are fairly fixed, and any significant decrease in fat is a result of starvation. The lipostatic hypothesis gained support from the discovery of leptin, which is a hormone secreted by fat cells. Leptin may be the substance used by the brain to monitor the amount of fat in the body.

There are several disorders related to eating habits, body weight, and body image that have their roots in psychological causes. Anorexia nervosa, which is more prevalent in females, is an eating disorder characterized by an individual being 15 percent below ideal body weight. Body dysmorphia, or a distorted body image, is key to understanding this disorder. Another related eating disorder is bulimia nervosa, which is characterized by alternating periods of binging and purging.

Another great motivator of action in humans and animals is thirst. A human can live for weeks without food, but only for a few days without water. Water leaves the body constantly through sweat, urine, and exhalation. This water needs to be replaced, and the body regulates our patterns of intake so that water is consumed before we are severely water depleted. The lateral hypothalamus is implicated in drinking. Lesions of this area greatly reduce drinking behavior. Another part of the hypothalamus, the preoptic area, is also involved. Lesions of the preoptic area result in excessive drinking.

As mentioned earlier, biological drives are those that ensure the survival not only of the individual, but also the survival of the individual’s genes. Like that of feeding and drinking, the motivation to reproduce relies on the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary gland and ultimately the production of androgens and estrogens. Androgens and estrogens are the primary sexual hormones in males and females, respectively. Without these hormones, sexual desire is eliminated in animals and is greatly reduced in humans.

As discussed in the “biological bases” of motivation, early theories on motivation relied on a purely biological explanation of motivated behavior. Animals, especially lower animals, are thought to be motivated by instinct, genetically programmed patterns of behavior. These early theories, along with arousal theory and drive-reduction theory, have given us an understanding of nature’s role in motivating behavior.

Abraham Maslow proposed a hierarchical system for organizing needs. This hierarchy can be divided into five levels. Each lower-level need must be met in order for an attempt to be made to fill the next category of needs in the hierarchy, which is illustrated in the diagram below.

Needs arise both from unsatisfied physiological drives as well as higher-level psychological needs, such as the needs for safety, belonging and love, and achievement. Along with instincts, drives, and arousal, needs provide an additional explanation for motivation. Maslow’s hierarchy is somewhat arbitrary—it comes from a Western emphasis on individuality, and some individuals have shown the ability to reorganize these motives (as, for example, in hunger strikes or eating disorders). Nevertheless, it has been generally accepted that we are only motivated to satisfy higher-level needs once certain lower-level needs have been met. The inclusion of higher-level needs, such as self-actualization and the need for recognition and respect from others, also explains behaviors that the previous theories do not.

Self-actualization occurs when people creatively and meaningfully fulfill their own potential. This is the ultimate goal of human beings according to Maslow’s theory.

Cognitive psychologists divide the factors that motivate behavior into intrinsic and extrinsic factors: that is, factors originating from within ourselves and factors coming from the outside world, respectively. A single type of behavior can be motivated by either intrinsic or extrinsic factors. Extrinsic motivators are often associated with the pressures of society, such as getting an education, having a job, and being sociable. Intrinsic motivators, in contrast, are associated with creativity and enjoyment. Over time, our intrinsic motivation may decrease if we receive extrinsic rewards for the same behavior. This phenomenon is called the overjustification effect. For example, a person may love to play the violin for fun but when he is a paid concert performer, he will play less for fun and view using the violin as part of his job.

An important intrinsic motivator is the need for self-determination, or the need to feel competent and in control. This need frequently conflicts with the pressures brought to bear by extrinsic motivators. The goal is to seek a balance between the fulfillment of the two categories of need. Related to the concept of self-determination is self-efficacy, or the belief that we can or cannot attain a particular goal. In general, the higher the level of self-efficacy, the more we believe that we can attain a particular goal and the more likely we are to achieve it, as well.

Although physiological needs form the basis for motivation, humans are not automatons, simply responding to biological pressures. Various theories have attempted to describe the interactions among motivation, personality, and cognition. Henry Murray believed that, although motivation is rooted in biology, individual differences and varying environments can cause motivations and needs to be expressed in many different ways. Murray proposed that human needs can be broken down into 20 specific types. For example, people have a need for affiliation. People with a high level of this need like to avoid conflicts, like to be members of groups, and dislike being evaluated.

Another cognitive theory of motivation concerns the need to avoid cognitive dissonance. People are motivated to reduce tension produced by conflicting thoughts or choices. Generally, they will change their attitude to fit their behavioral pattern, as long as they believe they are in control of their choices and actions. This will be discussed further in the Social Psychology chapter.

Sometimes, motives are in conflict. Kurt Lewin classified conflicts into four types. In an approach-approach conflict, one has to decide between two desirable options, such as having to choose between two colleges of similar characteristics. Avoidance-avoidance is a similar dilemma. Here, one has to choose between two unpleasant alternatives. For example, a person might have to choose between the lesser of two evils. In approach-avoidance conflicts, only one choice is presented, but it carries both pluses and minuses. For example, imagine that only one college has the major the student wants but that college is also prohibitively expensive. The last set of conflicts is multiple approach-avoidance. In this scenario, many options are available, but each has positives and negatives. Choosing one college out of many that are suitable, but not ideal, represents a multiple approach-avoidance conflict.

Emotions are experiential and subjective responses to certain internal and external stimuli. These experiential responses have both physical and behavioral components. Various theories have arisen to explain emotion.

Emotion consists of three components: a physiological (body) component, a behavioral (action) component, and a cognitive (mind) component. The physical aspect of emotion is one of physiological arousal, or an excitation of the body’s internal state. For example, when being startled at a surprise party, you may feel your heart pounding, your breathing becoming shallow and rapid, and your palms becoming sweaty. These are the sensations that accompany emotion (in this instance, surprise). The behavioral aspect of emotion includes some kind of expressive behavior: for example, spontaneously screaming and bringing your hands over your mouth. The cognitive aspect of emotion involves an appraisal or interpretation of the situation. Upon first being startled, the thought “dangerous situation” or “fear” may arise, only to be reassessed as “surprise” and “excitement” after recognizing the circumstances as a surprise party. This describes how the situation is interpreted or labeled. Interestingly, many emotions share the same or very similar physiological and behavioral responses; it is the mind that interprets one situation that evokes a quickened heart rate and tears as “joyful” and another with the same responses as “fearful.”

One class of theories relies on physiological explanations of emotion. The James-Lange theory posits that environmental stimuli cause physiological changes and responses. The experience of emotion, according to this theory, is a result of a physiological change. In other words, if an argument makes you angry, it is the physiological response (increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate) that prompts the experience of emotion.

There are many reasons why we now know that this theory is incorrect. We know that a given state of physiological arousal is common to many emotions. For example, a person might feel tenseness in his or her body as a result of being nervous, scared, or even excited. How, then, is it possible that the identical physiological state could lead to the rich variety of emotions that we experience? Another common experience that conflicts with the logic of the James-Lange theory is cutting onions. The physiological response to cutting onions is watering eyes; however, this physiological response does not make us sad.

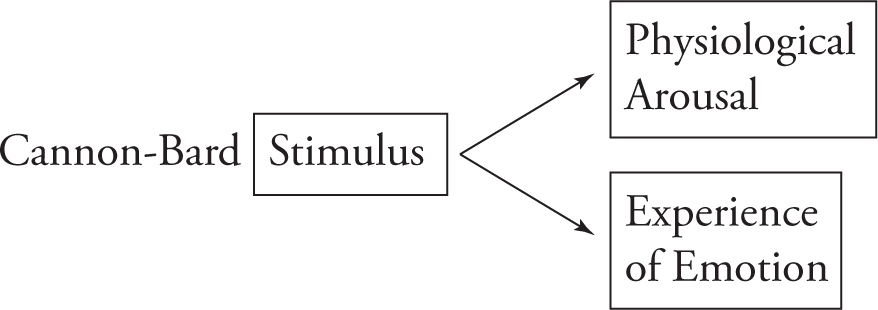

The Cannon-Bard theory arose as a response to the James-Lange theory. The Cannon-Bard theory asserts that the physiological response to an emotion and the experience of emotion occur simultaneously in response to an emotion-provoking stimulus. For example, the sight of a tarantula, which acts as an emotion-provoking stimulus, would stimulate the thalamus. The thalamus would send simultaneous messages to both the autonomic nervous system and the cerebral cortex. Messages to the cortex produce the experience of emotion (fear), and messages to the autonomic nervous system produce physiological arousal (running, heart palpitations).

The two-factor theory, proposed by Schachter and Singer, adds a cognitive twist to the James-Lange theory. The first factor is physiological arousal; the second factor is the way in which we cognitively label the experience of arousal. Central to this theory is the understanding that many emotional responses involve very similar physiological properties. The emotion that we experience, according to this theory, is the result of the label that we apply. For example, if we cry at a wedding, we interpret our emotion as happiness, but if we cry at a funeral, we interpret our emotion as sadness.

According to more recent studies by Zajonc, Le Doux, and Armony, some emotions are felt before being cognitively appraised. A scary sight travels through the eye to the thalamus, where it is then relayed to the amygdala before being labeled and evaluated by the cortex. According to these studies, the amygdala’s position relative to the thalamus may account for the quick emotional response. There are several parts of the brain implicated in emotional processing. The main area of the brain responsible for emotions is the limbic system, which includes the amygdala. The amygdala is most active when processing negative emotions, particularly fear.

Although theorists have disagreed over time about how emotions are processed, there has been a great deal of agreement about the universality of certain emotions. Darwin assumed that emotions had a strong biological basis. If this is true, then emotions should be experienced and expressed in similar ways across cultures, and in fact, this has been found to be the case. A scientist and pioneer in the study of emotions, Paul Ekman observed facial expressions from a variety of cultures and pointed out that, regardless of where two persons were from, their expressions of certain emotions were almost identical. In particular, Ekman identified six basic emotions that appeared across cultures: anger, fear, disgust, surprise, happiness, and sadness. These findings suggest that emotions and how they are expressed are innate parts of the human experience.

The evolutionary basis for emotion is thought to be related to its adaptive roles. It enhances survival by serving as a useful guide for quick decisions. A feeling of fear one experiences when walking alone down a dark alley while a shadowy figure approaches can be a valuable tool to indicate that the situation may be dangerous. A feeling of anger may enhance survival by encouraging one to fight back against an intruder. Other emotions may have a role in influencing individual behaviors within a social context. For example, embarrassment may encourage social conformity. Additionally, in social contexts, emotions provide a means for nonverbal communication and empathy, allowing for cooperative interactions.

On a more subtle level, emotions are a large influence on our everyday lives. Our choices often require consideration of our emotions. A person with a brain injury to their prefrontal cortex (which plays a role in processing emotion) has trouble imagining their own emotional responses to the possible outcomes of decisions. This can lead to making inappropriate decisions that can cost someone a job, a marriage, or his or her savings. Imagine how difficult it could be to refrain from risky behaviors, such as gambling or spending huge sums of money, without the ability to imagine your emotional response to the possible outcomes.

The limbic system is a collection of brain structures that lie on both sides of the thalamus; together, these structures appear to be primarily responsible for emotional experiences. The main structure involved in emotion in the limbic system is the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep within the brain. The amygdala serves as the conductor of the orchestra of our emotional experiences. It can communicate with the hypothalamus, a brain structure that controls the physiological aspects of emotion (largely through its modulating of the endocrine system), such as sweating and a racing heart. It also communicates with the prefrontal cortex, located at the front of the brain, which controls approach and avoidance behaviors—the behavioral aspects of emotion. The amygdala plays an especially key role in the identification and expression of fear and aggression.

Emotional experiences can be stored as memories that can be recalled by similar circumstances. The limbic system also includes the hippocampus, a brain structure that plays a key role in forming memories.

When memories are formed, the emotions associated with these memories are often also encoded. Take a second to close your eyes and imagine someone whom you love very much. Notice the emotional state that arises with your memory of that person. Recalling an event can bring about the emotions associated with it. Note that this isn’t always a pleasant experience. It has an important role in the suffering of patients who have experienced traumatic events. Similar circumstances to a traumatic event can lead to recall of the memory of the experience, referred to as flashback. Sometimes this recall isn’t even conscious; for example, for someone involved in a traumatic car accident, driving past the intersection where the incident occurred might cause an increase in muscle tension, heart rate, and respiratory rate.

The prefrontal cortex is critical for emotional experience, and it is also important in temperament and decision-making. It is associated with a reduction in emotional feelings, especially fear and anxiety, and is often activated by methods of emotion regulation and stress relief. The prefrontal cortex is like a soft voice, calming down the amygdala when it is overly aroused. The prefrontal cortex also plays a role in executive functions—higher-order thinking processes such as planning, organizing, inhibiting behavior, and decision-making. Damage to this area may lead to inappropriateness, impulsivity, and trouble with initiation. This area is not fully developed in humans until they reach their mid-twenties, explaining the sometimes erratic and emotionally charged behavior of teenagers. The most famous case of damage to the prefrontal cortex occurred to a man in the 1800s named Phineas Gage. Gage was a railroad worker who, at age 25, suffered an accident in which a railroad tie blasted through his head, entering under his cheekbone and exiting through the top of his skull. After the accident, Gage was described as “no longer himself,” prone to impulsivity, unable to stick to plans, and unable to demonstrate empathy. The accident severely damaged his prefrontal cortex, and while the reports about the change to his personality and behavior have been debated, this case led to the discovery of the role of the prefrontal cortex in personality.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for controlling the activities of most of the organs and glands, and it controls arousal. As mentioned earlier, it answers primarily to the hypothalamus. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) provides the body with brief, intense, vigorous responses. It is often referred to as the fight-or-flight system because it prepares an individual for action. It increases heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels in preparation for action. It also directs the adrenal glands to release the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine. The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) provides signals to the internal organs during a calm resting state when no crisis is present. When activated, it leads to changes that allow for recovery and the conservation of energy, including an increase in digestion and the repair of body tissues.

Many physiological states associated with emotion have been discussed. These include heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, sweating, and the release of stress hormones. An increase in these physiological functions is associated with the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) response. In order to measure autonomic function, clinicians can measure heart rate, finger temperature, skin conductance (sweating), and muscle activity. Keep in mind that different patterns tend to exist during different emotional states, but states such as fear and sexual arousal may display very similar patterns.

A concept related to emotion is the feeling of stress. Stress causes a person to feel challenged or endangered. Although this definition may make you think of experiences such as being attacked, in reality, most stressors (events that cause stress) are everyday events or situations that challenge us in more subtle ways. Stressors can be significant life-changing events, such as the death of a loved one, a divorce, a wedding, or the birth of a child. There are also many smaller, more manageable stressors, such as holidays, traffic jams, and other nuisances. Although these situations are varied, they share a common factor: they are all challenging for the person experiencing them.

As you may have inferred, the same situation may have different value as a stressor for different people. The perception of a stimulus as stressful may be more consequential than the actual nature of the stimulus itself. For example, some people find putting together children’s toys or electronic items quite stressful, yet other people find relaxation in similar tasks, such as building models.

What is most important for determining the stressful nature of an event is its appraisal, or how the individual interprets it. When stressors are appraised as being challenges, as one may perceive the AP Psychology Exam, they can actually be motivating. On the other hand, when they are perceived as threatening aspects of our identity, well-being, or safety, they may cause severe stress. Additionally, events that are considered negative and uncontrollable produce a greater stress response than those that are perceived as negative but controllable.

Some stressors are transient, meaning that they are temporary challenges. Others, such as those that lead to job-related stress, are chronic and can have a negative impact on one’s health. The physiological response to stress is related to what is referred to as a fight-or-flight response, a concept developed by Walter Cannon and enhanced by Hans Selye into the general adaptation syndrome. The three stages of this response to prolonged stress are alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. Alarm refers to the arousal of the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in the release of various stimulatory hormones, including corticosterone, which is used as a physiological index of stress. In the alarm phase, the body is energized for immediate action, which is adaptive for transient, but not chronic, stressors. Resistance is the result of parasympathetic rebound. The body cannot be aroused forever, and the parasympathetic system starts to reduce the arousal state. If the stressor does not relent, however, the body does not reduce its arousal state to baseline. If the stressor persists for long periods of time, the stress response continues into the exhaustion phase. In this phase, the body’s resources are exhausted, and tissue cannot be repaired. The immune system becomes impaired in its functioning, which is why we are more susceptible to illness during prolonged stress.

Richard Lazarus developed a cognitive theory of how we respond to stress. In this approach, the individual evaluates whether the event appears to be stressful. This is called primary appraisal. If the event is seen to be a threat, a secondary appraisal takes place, assessing whether the individual can handle the stress. Stress is minimized or maximized by the individual’s ability to respond to the stressor.

Research into stress has revealed that people generally show one of two different types of behavior patterns based on their responses to stress. The Type-A pattern of behavior is typified by competitiveness, a sense of time urgency, and elevated feelings of anger and hostility. The Type-B pattern of behavior is characterized by a low level of competitiveness, low preoccupation with time issues, and a generally easygoing attitude. People with Type-A patterns of behavior respond to stress quickly and aggressively. Type-A people also act in ways that tend to increase the likelihood that they will have stressful experiences. They seek jobs or tasks that put great demands on them. People with a Type-B pattern of behavior get stressed more slowly, and their stress levels do not seem to reach those heights seen in people with the Type-A pattern of behavior. There is some evidence that people with Type-A behavior patterns are more susceptible to stress-related diseases, including heart attacks, but may survive them more frequently than Type-Bs.

Biological Bases

motivation

primary drives

secondary drive

Olds and Milner

instinct theory

arousal theory

Yerkes-Dodson law

opponent process theory

drive-reduction theory

homeostasis

set point

ventromedial hypothalamus

lateral hypothalamus

Hunger, Thirst, and Sex

hypothalamus

leptin

blood glucose

glucostatic hypothesis

insulin

lipostatic hypothesis

anorexia nervosa

body dysmorphia

bulimia nervosa

pituitary gland

androgens

estrogens

Theories of Motivation

instinct

Abraham Maslow

self-actualization

intrinsic factors

extrinsic factors

overjustification effect

self-determination

self-efficacy

Henry Murray

need for affiliation

cognitive dissonance

Kurt Lewin

approach-approach

avoidance-avoidance

approach-avoidance

multiple approach-avoidance

Theories of Emotion

James-Lange theory

Cannon-Bard theory

Schachter-Singer two-factor theory

Paul Ekman

The Role of the Limbic System in Emotion

flashback

prefrontal cortex

autonomic nervous system

sympathetic nervous system

parasympathetic nervous system

Stress

stressors

transient

chronic

fight-or-flight response

Walter Cannon

Hans Selye

general adaptation syndrome

alarm

corticosterone

resistance

exhaustion

Richard Lazarus

Type-A pattern

Type-B pattern

See Chapter 19 for answers and explanations.

1. An example of a secondary drive is

(A) the satisfying of a basic need critical to one’s survival

(B) an attempt to get food to maintain homeostatic equilibrium related to hunger

(C) an attempt to act only on instinct

(D) an effort to obtain something that has been shown to have reinforcing properties

(E) an effort to continue an optimal state of arousal

2. An example of the Yerkes-Dodson law is

(A) the need to remain calm and relaxed while taking the SAT while letting adrenaline give a little boost

(B) performing at the highest level of arousal in order to obtain a primary reinforcer

(C) a task designed to restore the body to homeostasis

(D) the need to remain calm and peaceful while addressing envelopes for a charity event

(E) working at maximum arousal on a challenging project

3. A substance that can act directly on brain receptors to stimulate thirst is

(A) angiotensin

(B) endorphin

(C) thyroxin

(D) lipoprotein

(E) acetylcholine

4. Rhoni is a driven woman who feels the need to constantly excel in her career in order to help maintain the lifestyle her family has become accustomed to and in order to be seen as successful in her parents’ eyes. The factors that motivate Rhoni’s career behavior can be described as primarily

(A) intrinsic

(B) extrinsic

(C) hierarchical

(D) self-determined

(E) instinctual

5. Which of the following is less likely to be characteristic of a Type-A personality than of a Type-B personality?

(A) A constant sense of time urgency

(B) A tendency toward easier arousability

(C) A greater likelihood to anger slowly

(D) A higher rate of stress-related physical complaints

(E) A need to see situations as competitive

6. Sanju is hungry and buys a donut at the nearby donut shop. According to drive-reduction theory, she

(A) has returned her body to homeostasis

(B) will need to eat something else, since a donut is rich in nutrients

(C) will continue to feel hungry

(D) will have created another imbalance and feel thirsty

(E) has raised her glucose levels to an unhealthy level

7. Jorge walks into a dark room, turns on the light, and his friends yell “Surprise!” Jorge’s racing heartbeat is interpreted as surprise and joy instead of fear. This supports which theory of emotion?

(A) The opponent-process theory

(B) The James-Lange theory

(C) The Cannon-Bard theory

(D) The Schachter-Singer theory

(E) The Yerkes-Dodson law

8. A person addicted to prescription drugs started by taking the prescribed amount, but then increased the dosage more and more to feel the same effect as when she first started. This progression is consistent with the

(A) instinct theory

(B) arousal theory

(C) two-factor theory

(D) drive-reduction theory

(E) opponent-process theory

9. All of the following are symptoms of chronic stress EXCEPT

(A) hypertension

(B) immunosuppression

(C) chronic fatigue

(D) tissue damage

(E) suppressed appetite

10. The hypothalamus does which of the following?

(A) Serves as a relay center

(B) Regulates homeostasis

(C) Aids in encoding memory

(D) Regulates most hormones to be secreted

(E) Regulates fear and aggression

Respond to the following questions:

Which topics in this chapter do you hope to see on the multiple-choice section or essay?

Which topics in this chapter do you hope to not see on the multiple-choice section or essay?

Regarding any psychologists mentioned, can you pair the psychologists with their contributions to the field? Did they contribute significant experiments, theories, or both?

Regarding any theories mentioned, can you distinguish between differing theories well enough to recognize them on the multiple-choice section? Can you distinguish them well enough to write a fluent essay on them?

Regarding any figures given, if you were given a labeled figure from within this chapter, would you be able to give the significance of each part of the figure?

Can you define the key terms at the end of the chapter?

Which parts of the chapter will you review?

Will you seek further help, outside of this book (such as a teacher, Princeton Review tutor, or AP Students), on any of the content in this chapter—and, if so, on what content?