David was only six when his father hired a launch to take the family on an expedition to explore Twenty Day Island in Bass Strait, about twelve miles from the fishing village of Bridport where they always spent the summer. The launch’s engine had sputtered into silence near the rocky shore, when David heard the drone of another engine. There was not a boat to be seen in any direction.

Then, above in the sun-bright blue, David glimpsed something extraordinary. An aeroplane! The first he had ever seen! David nearly jumped off the launch into the water in his excitement. He waved and waved. And watched and watched until the little plane disappeared beyond the horizon. He knew then that he wanted to fly too. One day. When he was a man. Bobbing about in a boat over choppy sea was an adventure. But surely it could not compare with rushing through the air, up among the clouds, looking down on the world spread

The vice-free de Havilland Tiger Moth (AWM neg. no. 002157)

out below like a multi-coloured tapestry. The pilot was pioneer aviator Bert Hinkler and David’s passion for planes had been kindled.

In 1931, when David was eight, Charles Kingsford Smith came on a barnstorming visit. On 1 March, Tasmania had its first Air Pageant at the recently established Western Junction airfield. Interest was intense and so many people flocked to see the show that the newspapers reported Tasmania’s first traffic jam, with cars banked up for a mile or more.

Impatient to reach the display, David hopped out of his father’s Essex car and eagerly walked the final stretch. His unmarried aunt, a feisty woman who lived with the family, gladly parted with ten shillings to go up with the famous pilot on a brief circuit beyond the airfield.

‘Can I go up too?’ David begged.

‘No!’ said his parents, very firmly.

In those Depression years, times were tough for his father, a dentist whose patients could not always pay their bills. And because David was their youngest son, his mother always worried about him. He had to content himself with inspecting the amazing machine on the ground and questioning his aunt over and over about every detail of the flight.

David cut photos of the historic event out of the paper. Then over the next months he saved the tuppence his uncle gave him each week for a pie from the tuckshop, until he had enough money to buy a big scrapbook, into which he carefully pasted all the cuttings. Over the years he added other items about aviation as he found them. All the while, watching and waiting for his chance to fly.

David, Bow in Launceston Church Grammar School First Four, 1940

By the time David was thirteen he spent most summer Saturdays on the water. He loved the wide brown Tamar River studded with swans, its tidal waters ebbing and flowing between reedy banks where native hens ran with raucous calls. Training in the mornings, racing in the afternoons, year by year he had progressed from the Junior rowing crew to the Seconds and at last to the Firsts, rowing at Number Three or Bow. He loved the teamwork, the camaraderie, the shrill voice of the young coxswain chanting, ‘In. Out. In. Out,’ and the deep voice of the coach shouting instructions across the water through his megaphone. He thrilled to the thrust, the glide, the power generated by four sets of shoulders, four pairs of arms pulling on the oars. It seemed like the steady beat of wings making the boat fly across the water.

Winter Saturdays were different. On wild wet days, or when fog seeped up from the river, or dark clouds shrouded the Western Tiers, he stayed home, disappointed but determined, plugging away at the maths he would need if he was ever to become a pilot. But when the clouds were light and playful and the sun danced over Mount Barrow, he would slap together two sandwiches thick with cheese, peanut butter or blackberry jam, wrap them hastily and shove them in a pocket, stuff two apples in the other, and grab his bike, shouting ‘I’m off, Mum!’

Whistling, he would pedal uphill out of town. When he reached the flat road that led to the Western Junction airfield, speeding by the clipped hawthorn hedges still speckled with red berries, he laughed as he felt the wind rushing through his hair. He counted down the minutes - fifty, forty-five, forty - until he would catch his first glimpse of a windsock, a hangar, a plane… The Northern Tasmanian Aero Club had set up its headquarters in a shed at the airfield and members gave joy flights at the weekends. David soon learned to distinguish between the different types of Moth aircraft, boxy little biplanes constructed of wood and fabric. There were Gipsy Moths, Fox Moths, and a Leopard Moth. But his favourite was the Tiger Moth. Each Saturday he promised himself that one day he would learn to fly a Tiger Moth.

He prowled round all the machines, watching preflight checks, listening to conversations between pilots and mechanics, thrilled when someone called ‘Lend a hand, will you, lad,’ or even, ‘Want to look at the instrument panel?’ The sights, sounds and smells would later fill his dreams.

At school, David persevered with maths, but English and history were his favourite subjects, especially poetry and modern European history. As he scanned the papers for any items about aviation, he could not help noticing news about the growing unrest in Europe. At first, small paragraphs were tucked away in back pages, behind local and Australian news. But as the months went by they moved closer to the front of the paper and had bigger headlines, as the Nazis grabbed more and more power in Germany.

In March 1938, German troops entered Vienna, the once-proud capital of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Austria was declared part of the German Reich. By August, as Germany began to mobilise, the name Hitler had become a household word, evoking anxiety and fears for the stability of the precarious peace established after the Great War.

In September, half a world away, schoolboy David studied cartoons of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain caving in to Hitler at the infamous Munich Conference, which established Nazi Germany as the dominant power in Europe, with Fascist Italy under Mussolini in support. As France and Britain followed a policy of appeasement, Nazi troops occupied Czechoslovakia. But in Britain an outcry against Chamberlain arose, and David noted the name of its leader, Winston Churchill, soon to become another household word epitomising resistance to Nazism and Fascism.

If Britain went to war, Australia would follow. It threw a long shadow over the eagerly awaited summer holidays, spent, as usual, at the family beach house. The young people partied around the bonfire on Mattingleys Beach, as they did every New Year’s Eve, but lads whose eighteenth birthday would fall in 1939 were quieter than usual.

Staring into the leaping flames, sixteen-year-old David had a heavy feeling he was looking into the fire which seemed about to engulf Europe, its fierce heat scorching and destroying lives around the world.

But despite the foreboding, it was a glorious summer, that last summer of peace. David and his friends swam, sunbaked and walked for miles along the pristine beaches of the great sweep of Andersons Bay. At dusk, they threw their lines into the Brid River for blackfish, though David secretly hoped he wouldn’t catch any. On shooting expeditions in the bush with his father and brothers, he deliberately missed the gentle wallabies in the gun’s sight, unable to bring himself to kill them.

David had gained the Royal Lifesaving Society’s Award of Merit and Instructor’s Certificate and now drilled younger swimmers in lifesaving techniques. He had never forgotten the terrible day six years before, when, despite the efforts of his older brothers Max and Brian to save them, two boys, one also named David, had drowned.

When David turned seventeen on 14 June 1939, war in Europe seemed inevitable. Hitler and Mussolini had signed ‘The Pact of Steel’, a ten-year military and political alliance, and although non-aggression pacts between Germany and other countries were collapsing, a new one with the USSR strengthened Germany’s position. Poland’s sovereignty was threatened. Britain and France had warned Germany they would stand by Poland. But Germany invaded on 1 September. Two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany.

David, Launceston Church Grammar School prefect, 1939

The heavy black print of the Launceston Examiner headline of 4 September seared itself into David’s brain. BRITAIN AT WAR WITH GERMANY.

A second headline, TASMANIAN TROOPS CALLED TO THE COLOURS, appeared over a photo. David studied the photo closely. ‘How long before I’m in uniform?’ he wondered.

By the end of September, when Germany and the USSR had invaded and divided Poland between them, Britain had sent 158 000 men to fight in France and the

Royal Air Force (RAF) had begun its propaganda raids, dropping thousands of leaflets over Germany. David’s album bulged with newspaper pictures of warplanes, both British and German.

In December, celebrations marking the end of the school year were subdued. Some boys who had turned eighteen went straight off to enlist. Through Christmas and January, David was aware of faces missing from the beach scene. His older brother Max, home on holidays from teaching in Brisbane, talked of enlisting in the Royal Australian Navy, because the sea had always been his passion. And when term began in February 1940, David found that teachers at his school had left to join the Services.

By Easter, Germany had invaded Norway and Denmark, and a British force sent to help Norway singe Herr Hitler’s moustache failed for lack of air power. In May, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium and pierced French defences. On 29 May the heroic evacuation of British forces began at Dunkirk in France.

Then, on David’s eighteenth birthday, the Germans entered Paris. For the free world it was a day of mourning as this great city, symbol of culture and popular revolution, fell once more victim to tyranny.

Every day, David rose early to read the war news in the paper before setting off for school. In the evening he gathered with the family round the wireless to hear the latest broadcast, watching their expressions become more serious as the news worsened. In July, the RAF began night bombing of Germany. Germany had unleashed the force of its Luftwaffe on Britain, in an attempt to knock out as many airfields and defences as possible prior to invasion. But the German planes met with valiant opposition. Avidly, David pored over the accounts of the courage and daring of the fighter pilots in their Spitfires and Hurricanes, who with such skill and tenacity harried and attacked the Heinkels, Junkers and Messerschmitts sent by Hitler to blast Britain into submission. The stories of this small band of weary but indomitable airmen in their battle-worn planes, patrolling the English skies, repulsing invaders, inspired him and strengthened his determination to join them in defending the heart of Empire. He was moved by Winston Churchill’s tribute, ‘Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.’

By mid-August, when the Battle of Britain was at its peak, one hundred and eighty German planes had been shot down. But still more came over in wave after relentless wave, pounding London day and night - the beginning of the Blitz.

At sea, German U-boats threatened vital supplies of food and fuel, and troops arriving from Commonwealth countries.

At eighteen David was not old enough to vote. But he could pay taxes and legally drive a car. And he could join the armed forces, which seemed the right thing to do. The only thing. Everyone in the free world had to take responsibility for opposing the evils of Nazi aggression. But war meant mayhem and mass destruction on both sides. Created widows and orphans. Destroyed homes. Robbed parents of children in whom they had invested so many years of care and love and hope. ‘How will Mum and Dad feel if I enlist?’ he asked himself again and again.

One spring evening David was walking home with his father through City Park, where since he was small he had always loved to watch the monkeys’ antics. The question which had kept his heart and mind in turmoil for months spilled out.

‘Dad, when I leave school, I want to join the Air Force. That’s all right with you, isn’t it?’

His father was silent, but a blackbird scratching among the oak leaves scolded loudly. His father’s footsteps slowed, then stopped. Two children ran by, laughing as they pelted each other with acorns.

‘I’ve been expecting this,’ his father replied at last. ‘And so has your mother. Of course we aren’t happy about it. But we understand. And you have our blessing.’

David gripped his father’s strong square hands. The hands which extracted teeth in the surgery and tended flowers in the garden. The hands which had shown him how to hold a cricket bat, wield an axe, plant a rosebush, prune an apple tree.

‘Will you tell Mum or shall I?’ he asked.

‘Let me break it to her first,’ his father said. ‘Then you can talk to her.’

When they sat down to tea, David’s mother’s eyes were red and he knew at once that his father must have spoken to her. But the family talked of other things, focusing on end of year plans and David’s brother Brian’s return from teaching in Armidale.

After the meal, everyone gathered as usual around the wireless, listening intently to the progress report on the newly opened North Africa campaign, hearing with dismay that the Germans had extended their bombing raids over Britain.

David carried the teacups out to the kitchen where his mother was running water into the sink. ‘Dad’s told you,’ he said. It was more a statement than a question. His mother nodded, not trusting herself to speak. He hugged her and held her close for what seemed a moment, but was actually almost three wordless minutes as he realised, looking up at the trusty old clock on the dresser, which had already ticked through World War I.

‘When?’ she asked, holding him at arm’s length so she could gaze on him.

‘As soon as I’ve left school.’

She nodded again. ‘Your father and I expected this. After all, you’ve always loved planes and this is your chance to learn to fly.’ She smiled wanly. ‘But you’re doing it for the right reason, Viddy,’ she added with pride. ‘We have to stand up to those bullies. There must always be an England and England shall be free,’ she said, referring to a song David had been playing for months on the sitting room piano. ‘Now you must get back to your homework. Only six more weeks to your final exams.’

David needed no reminding. He was a conscientious student, and wanted to do well. Before the war had blown up he had set his sights on going to university and becoming a teacher. It was something of a family tradition. His father’s parents had been teachers, with their own school at Emerald Hill in Melbourne. Now both his older brothers were teachers. It was a good profession.

In his last week at school, the headmaster called David to his study.

‘Has the war affected your plans too?’ he enquired. ‘Will you be joining up like so many others?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘The Air Force, I suppose.’ The headmaster knew David’s passion for planes.

‘I hope so.’

‘Well, they’ll be getting a good recruit in you. But if you’re not called up for a while - lots of fellows have enlisted but had to wait for their call-up - I’d be glad if you’d help us out here. We’re losing another couple of teachers to the forces and need replacements. Think about it.’

‘I don’t know whether I could change from schoolmate into teacher, sir,’ David demurred.

The headmaster looked at the tall, fresh-faced young man, whose modesty, quiet humour and sense of responsibility had endeared him to students and staff alike. ‘You’ve been a prefect, wicket-keeper in the Second Eleven, and rowed in the First Four. You’re respected and well liked. You won’t have any trouble. I’ll give you classes in the lower school, where you’re looked up to. Share your passion for poetry with them and tell them stories from English history which they’ll never forget. Anyway, see how you go at the recruiting office. If they can’t take you straightaway, we’ll be glad to have you back and pay you for your time and effort.’

His mother was pleased when David told her of the headmaster’s offer. It was a good fallback position, if his call-up didn’t come straight through. He knuckled down to revision and the approaching exams with some peace of mind, if not confidence.

The final school speech night was emotional. Would David ever again see some of these fellows he had grown up with over the last twelve years? How many would still be around in a year’s time? How many names would be up on the school honour board, with a gold asterisk beside them denoting the final sacrifice? Would his? Or would the war be over before he had the chance to make his contribution?

It was a quiet Christmas and New Year. With growing impatience, David awaited his exam results and a response to his application for entry into the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). At last one of the letters he was hoping for came. He had passed all his Leaving Certificate (Year Twelve) subjects, with As in English and history, Bs in the rest. Now he must wait for his call-up.

And wait he did, through much of 1941. Processing applications took time, and there were not enough places in the Empire Air Training Scheme for the volunteers who wished to become aircrew. Month after month he waited for the envelope which seemed as if it would never come, while increasingly grim news came from the war zones. These now spanned the Sudan, Eritrea and Abyssinia, (Ethiopia), Greece, Crete, Syria, Iran and the Baltic States. And Germany had launched a new North Africa offensive where the Diggers’ heroic resistance led to the insulting Nazi epithet ‘Rats of Tobruk’ becoming a byword for courage and tenacity.

Air raids on London had been stepped up again. In the industrial city of Coventry, the superb Gothic cathedral was reduced to rubble. Britons had stoically endured the devastation and disruption of their lives caused by the Blitz. But the destruction of such beauty and tradition galvanised a new spirit of determination and resistance. U-boat attacks also intensified. The battle cruiser Hood, pride of the Navy, was sunk off Greenland by the

German super battleship Bismarck, which was in turn sunk by the Royal Navy. In June, eight days after David’s 19th birthday, Hitler broke the non-aggression pact and German forces invaded Russia.

‘It’s come at last!’ David announced to his parents in October, on receiving the letter requesting him to attend an interview for entry to the RAAF.

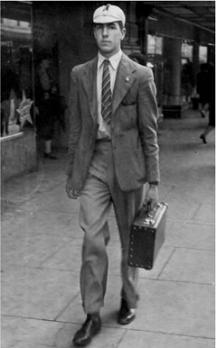

Wearing his best jacket and tie, shaven, his thick dark hair carefully combed, his shoes polished, David presented himself at the recruiting office. After completing a plethora of forms, answering a myriad of questions, he was called for a short interview. Standing straight and attentive before three uniformed officers, he noted their ranks and focused on the most senior.

‘Why do you want to join the Air Force?’ the Flight Lieutenant asked.

‘To serve my king and country, sir,’ David answered without hesitation.

‘Do you know anything about flying?’ another asked.

‘I’ve been keen on planes, sir, ever since I saw Bert Hinkler, then Charles Kingsford Smith at the Air Pageant.’

The officers smiled for the first time. ‘That was a good show!’ one exclaimed. After a medical examination David returned by train to Launceston to await results yet again.

On 2 December a letter arrived On His Majesty’s Service, notifying him that he had been placed on the Royal Australian Air Force Reserve. Call-up was unlikely before April 1942, but he was required to commence a course of ground subjects immediately. Disappointed yet pleased, David began night classes, the first step towards his goal. More maths and some physics, with morse code and aircraft recognition stimulating new interest and promising action in the air eventually.

International events escalated dramatically. Japan, which had invaded China and Manchuria in the 1930s, suddenly revealed further imperial expansionist ambitions. On 7 December, the Japanese Air Force bombed the American naval base Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, and British Malaya. Next day Britain and Australia declared war on Japan. So did the USA, up until then neutral. Three days later the USA declared war on Germany and Italy.

Now the world was at war.

With the fall of Malaya to the Japanese before Christmas, and war raging on Australia’s doorstep, David grew increasingly frustrated, chafing to be in uniform. Earlier in the year, the biggest contingent ever to leave Tasmania had embarked on the liner Queen Mary, now converted to a troopship. Although the movement was an official secret, it was impossible to disguise the presence of such a large and impressive vessel in Hobart, and people flocked to see the splendid ship and to farewell loved ones.

David caught a special train from Launceston, travelling over four hours, to join the crowds gaping at the great grey giant towering above the fishing boats in the historic deepwater harbour. He took in every detail and would have given anything to change his civvies for uniform, to be striding up the gangplank, kitbag on shoulder. Instead he just had to trudge to the station for the rackety trip home in the cold and dark, with a long walk at the end.

At the New Year’s Eve beach party there were now many more girls than boys. David had little heart for celebrating. He just wanted to be up and away. Then, early in January 1942, an unexpected letter arrived. It was a compulsory call-up for Army service. Within days he was in khaki, drilling at the Launceston Showgrounds with more than a hundred other raw young recruits. For four months he marched and trained.

Just before his 20th birthday the long-awaited summons to the Air Force came. David went straight to Hobart for a stringent medical examination, after which he was sworn in.

Australia was a participant in the Empire Air Training Scheme to provide aircrew to supplement Britain’s Royal Air Force. Recruits might eventually be sent for flying training to Canada or Rhodesia, but they all did their initial training in Australia. As one of a group of Tasmanians entering No. 1 RAAF Initial Training School at Somers, Victoria, on 19 June, David became a Blue Orchid, as RAAF personnel were dubbed in army slang. Air Force blue was the colour he was to wear for the next four and a half years.

RAAF officer’s cap badge, which David hoped eventually to wear