Chuffed to find three cakes in the mail awaiting him at Brighton, David exclaimed, ‘Let’s have a party!’ and invited some mates to warm their new sixth-floor room in the Metropole Hotel. Then, keenly aware that seamail took three months to reach Australia, he wrote Christmas letters and five dozen cards.

Now the course intensified. The men studied signals, armaments, airmanship encompassing modern combat methods, aerodrome control, navigation and operations, intelligence, leaving a ditched aircraft, and evasion and escape from enemy territory. Operational crews were provided with some ingenious aids to help them escape. A silk scarf, which could be tucked easily into a pocket, was printed with a map. A compass was concealed in a comb or a button, or under the eraser of a pencil. Flying boots concealed a special blade to cut off the tops, leaving footwear like normal shoes. There was a razor for maintaining appearance, and for survival

Metropole Hotel, Brighton, England, home to newly

arrived Australian aircrew

a collapsible rubber water bottle and high sustenance Horlicks tablets. A wallet full of money in the currencies of countries in which the airmen might find themselves completed the kit.

A card detailing The Responsibilities of a Prisoner of War, printed NOT TO BE TAKEN INTO THE AIR, was issued to each airman, who was required to memorise the information. It was impressed upon all aircrew that under the 1929 Geneva Convention a prisoner of war is required to give only his name, rank and number. The Enemy is known to attach the utmost importance to the interrogation and search of prisoners, but he can learn nothing from a silent and resolute prisoner whose pockets are empty.

The men were urged to remember that a prisoner who systematically refuses to give information is respected by his captors and that a silent and resolute prisoner without articles or papers of any sort is an interrogator’s nightmare.

Point by graphic point instructions were given on behaviour under interrogation: what the Enemy would try to find out; how information would be obtained by the Enemy. Sources included examination of captured aircraft and material, search of prisoners for notebooks, letters, diaries and any other incriminating documents or papers, and interrogation either by direct questioning or by indirect methods. Among many others, both subtle and crude, methods might involve fraternisation, intimidation, bribery, ill treatment, hidden microphones, agents, stool pigeons and propaganda. Do’s and dont’s and the rights of a prisoner were reiterated, as well as the warning, A prisoner is always surrounded by his enemies. Trust no one.

Instructors from three Advanced Flying Units spoke about their courses, and David wondered, ‘Where will I be posted?’ The men were shown films which dealt with aircraft recognition, camouflage from air observation, protection from gas. They also saw a British film showing the North Africa campaign, plus one about Russian guerrilla warfare and even a German film on the Nazi invasion of Poland. And although they laughed at the poster to be seen everywhere - Be like Dad, keep Mum - the film Next of Kin, shown twice to drive home the message - careless talk costs lives - was very sobering. No airman wanted his family to receive one of those telegrams KILLED IN ACTION or MISSING, PRESUMED DEAD. David also spent hours in the intelligence library, studying the ‘gen’ on German aircraft and equipment, location of German units and details of the different war fronts.

There was plenty of practical work too, with more sessions in the Link Trainer, substituting for actual flying. Gunnery practice included clay pigeon shooting - ‘Much harder than it looks,’ David declared - and firing practice with Brownings from different types of turrets, aircraft cannon, Sten guns, sub-machine guns and pistols.

Nobody enjoyed the afternoon spent in the baths practising how to escape from a ditched aircraft. ‘This is no fun,’ they spluttered. But the memory of the unforgiving Atlantic motivated everyone to master the skill. Clambering into and out of aircraft dinghies in full flying kit, heavy, sodden and cumbersome, demanded real effort. David, knowledgeable in lifesaving, took it very seriously, encouraging and assisting the others. He was used to small boats and rowing fours, but handling these circular rubber dinghies was quite another matter.

‘They’ve certainly got a will of their own!’ he muttered after several attempts to get one right side up. ‘Let’s hope we never have to use one.’ A hope fervently echoed by all the shivering airmen, choking and spitting mouthfuls of water.

‘You look like a drowned possum.’

‘Well, you look as miserable as a bandicoot.’

The men joked as they stripped off their wet clobber, leaving it to be donned by the next group, but they all knew ditching was no laughing matter.

After the cricket season ended, David continued swimming, and enjoyed trying badminton. He also gave boxing a go, but quickly gave it up, joking to Peter, ‘A bloody nose doesn’t suit me.’

Now in addition to blackout duty and gun watch there was fire watch, fortunately uneventful, although there were four successive nights of air raid alerts as the German offensive against London increased again. David discovered stargazing and learned to identify the unfamiliar Northern Hemisphere constellations, pleased to be able to recognise the North Star in the Plough. He missed Alan’s company when his friend was posted to an Advanced Flying Unit, but an unexpected visit from cousin Phil provided another opportunity to talk about family and home. Phil was in Coastal Command, flying Liberators from Northern Ireland, and David was envious hearing that on recent flights he had been diverted to Iceland and Gibraltar. ‘You lucky blighter!’

David and his mates seized every chance to explore more of England’s beautiful south coast by double-decker buses, which gave splendid views of country and coastline. David and Ian spent a day’s leave at Shoreham Air/Sea Rescue Station, glad to learn how dinghies were dropped to ditched airmen. A Mosquito doing aerobatics with one engine stopped was really impressive.

‘I wouldn’t want to try that in a Spitfire!’ David exclaimed.

‘Nor would I,’ grinned Ian, appreciating the joke that Spitfires are single-engined.

David and Peter visited Newhaven, base for motor torpedo boats, which they watched on manoeuvres. Travelling west, through woods of yellowing chestnut trees, David was enthralled by the layers of history which every mile revealed - Roman roads, Saxon forts, Norman castles, medieval churches. The most recent layer, imposed by this 20th century war, consisted of well-concealed military encampments in belts of forest, and trip wires at a height of 15 feet above open fields to prevent enemy planes from landing troops.

Quaint place names appealed to his sense of humour and he joked about Henfield, ‘Where are the chooks?’; Burpham, ‘Who cooked the dinner?’; and Bury, ‘How big is the cemetery?’ Peter usually responded in kind to David’s play on words, but on this day he was quiet. As they wandered into the ancient graveyard of a little Norman church, David could not help quoting from Gray’s ‘Elegy’: ‘Each in his narrow cell forever laid, The rude Forefathers of the hamlet sleep’. He roamed among lichened and leaning headstones, reading epitaphs: informative, fulsome, sometimes unintentionally funny, but always revealing in their grappling with mortality.

Peter usually joined David and they would muse and ponder and sometimes chuckle together. But this day Peter sat on an old stone wall, staring at the lengthening shadows, gazing towards the setting sun, ‘leaving the world to darkness and to me,’ he quoted in return, as David came and sat beside him.

‘Do you ever wonder how many more sunsets we will see?’ Peter asked.

David nodded. ‘Every day.’

In the unit the men did not talk about the likelihood of death which hung over them. Each confronted his own demons in private, secretly. Some considered it bad form to discuss it. Others, more superstitious, feared it might jinx them. Occasionally, someone deeply troubled might talk it over with the padre.

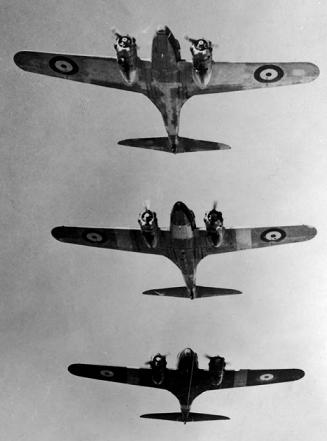

They had survived the perils, day by day and night by night, of the three-month sea voyage. They had seen the devastation of London. They had watched a German pilot plummet to his unmarked grave in the English Channel. They had observed the bombers in purposeful formation heading for Germany. Every man knew his name could be on a casualty list any day - KILLED, or MISSING IN ACTION. Every man knew it could be his next-of-kin, his loved ones, receiving a telegram which would plunge them into mourning and a grief which time would never heal.

So they soldiered on, doing their duty to their nation, upholding the ideals of peace, justice and freedom. They drilled, trained, learned about weapons of destruction, and nurtured the spirit of survival by making fun out of hardships and joking about adversity. Laughter was their most powerful weapon against fear and despair.

‘Death is so final, isn’t it?’ Peter said. ‘Or is it?’ He turned to David, desperate for the reassurance he knew David could give. They had both been at the same church school, they had attended chapel services together, sung the same hymns, listened to the same talks by the chaplain. David’s faith had always seemed so sturdy. He had always seemed so sure, never doubting that this life was a prelude to something even better.

David summoned all his strength for his friend in crisis. With one hand he gripped Peter’s cold one. With the other he pointed to a nearby monument, a weatherbeaten cross, on which could still be deciphered the inscription, I know that my Redeemer liveth.

‘Heaven’s real,’ he said. ‘Some of us will make it sooner than others to our Father’s house of many rooms. And the place is ready - for you, for me, whenever…’

‘I worry about my sister,’ Peter blurted out. David knew she had been badly burned as a child and Peter was very protective of her. ‘I’ve left her all I’ve got, in my will. That’s why I might sometimes seem a bit of a Scrooge. I want to make sure there’s something for her, if I’m not there to take care of her after Mum and Dad go.’

David nodded in quiet sympathy. He knew intuitively that it would be harder for those left behind than for those who went ahead. He stood up. ‘Let’s look inside the church before it gets dark, shall we?’ They walked past the brooding bulk of yew trees and entered the little church, solid and still under its ancient stone arches. As they were about to kneel in a pew at the back, the vicar came down the chancel steps.

‘Hullo, lads,’ he greeted them, and noting the flashes on their jackets, he went on, ‘You won’t find a church like this in your part of the world. People have been praying here for over 900 years. Quite a thought, isn’t it? I’m sorry there’s not time to show you round. But if you miss the last bus, it’s a long way to walk. At least I can say a blessing over you before you go.’

And so the words which had brought peace to the hearts and minds of many generations were said yet again to comfort the young airmen so far from home.

It was a silent ride back. As they climbed the stairs to their room, Peter said, ‘Thanks, Dave.’ ‘Any time,’ David replied. That night they had their 12th consecutive air-raid alert. It was Brighton’s 876th.

Two days later, David bought a copy of Cassell’s Anthology of English Poetry bound in maroon leather. At twelve shillings and sixpence it cost almost a day’s pay, but was worth every penny. He immersed himself in it in spare moments, finding solace in the words of others who had rejoiced in life and grappled with its deepest questions. Then, on Remembrance Sunday, while all 800 trainees attended a special parade service at 1100 hours, the alert went. David wrote in his diary, One could not but think what an excellent target we were! It was a sombre day.

Blustery cold winds had stripped the last crimson leaves from creepers clinging to cottage walls. In the woods, only the oaks still held fast to a remnant veil of their dense summer canopy, dull gold against their massive dark trunks, when David and Ian made another excursion, to Portsmouth. Here sights waited which they would never forget. Britain’s chief naval base since Tudor times, Portsmouth had been heavily blitzed. Acre upon acre of the city, especially the old town, had been flattened. Many buildings of great historic importance had been gutted or completely destroyed. Their rubble still lay in great piles along both sides of the streets. Only the occasional building stood intact in the wasteland.

‘It’s a ghost city!’ David exclaimed, more appalled by the utter devastation than he had been so far. ‘And this is what we’re being trained to do to German cities,’ he grieved silently.

They wandered down to the landing where sailors and emigrants in past centuries had embarked for the six-month voyage to Australia. David thought of his great-great-grandmother who had taken a clock inlaid with mother-of-pearl and a fine gilt-framed mirror among her possessions when she set out for Tasmania in 1836. What had been her thoughts, her feelings, as she boarded the sailing ship, leaving behind everyone, everything she knew?

David and Ian walked along the docks to see one of Britain’s great national treasures, Nelson’s ship Victory. The crucial Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 marked triumph over Napoleon, but resulted in Nelson’s death. ‘What were his last thoughts?’ David wondered.

London was still a magnet, with its wealth of places to discover. Thirty-six and forty-eight hour leave passes gave more opportunities for catching up at the Boomerang Club with friends from other units, like Tas Williams from Derby. Tas, sturdy in build and spirit, so typical of the little mining town from which he came, and so worthy of his proud name, Tasman. As he and David laughed at the monkeys in London Zoo, they recalled boyhood days watching other monkeys in Launceston’s City Park, and basked in warm memories of Bridport summers they had shared. At Madame Tussaud’s Waxworks, wandering among amazingly lifelike figures of the illustrious and the notorious, they laughed again, hearing another visitor mistake one for an attendant and ask for directions.

David visited the Tower of London with Ian, rapt to be shown over it by a Beefeater in traditional livery. On a very different occasion the Agent-General for Tasmania, a family friend, took him to the London Rotary Club weekly lunch, when three lemons auctioned for charity brought £3 each, and a banana, rare indeed in wartime Britain, fetched £3/5/!

After eleven weeks at Brighton, David was promoted to Flight Sergeant and they all learned of their new postings. According to mustering, classification by specific skills, pilots, bomb aimers, navigators, air gunners and wireless operators were sent on to their relevant units for further training. It was time to say goodbye to many whom David had got to know well since the first days at Somers.

‘Be good! Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do,’ they told each other.

‘Then that gives me plenty of scope!’ came the laughing reply.

But underneath the banter, they were wondering if they would ever meet again.

David was glad Peter and Ian were going with him to No. 3 Advanced Flying Unit at South Cerney near Cirencester in Gloucestershire. After two busy days packing up, obtaining all the necessary clearances and saying farewells, on 23 November they rose before dawn and set out on the next stage of their journey. It would be their third flying course, and they were looking forward to getting back in the air.