Three trains and six hours after they left Brighton, the young pilots arrived in Cirencester, eager for this new phase of their adventure. South Cerney, like Point Cook, was a peacetime station.

‘We’ll enjoy it here,’ they exclaimed on seeing centrally heated brick barracks with mod cons and huge permanent hangars. But, like Point Cook, it had been expanded to accommodate the wartime influx of aircrew and aircraft.

‘Let’s make the most of it,’ David declared on learning that they would only have twelve days of relative luxury before being dispersed to satellite airfields.

In contrast to Point Cook’s flat, dry, sparsely populated expanse, South Cerney was in the heart of the Cotswolds, gentle wooded hills laced with winding valleys, dotted with some of England’s most picturesque stone villages and medieval market towns. David could hardly wait to start exploring.

RAAF Avro Ansons in formation

But at first there was no opportunity. The Advanced Flying Unit program consisted of eight-period days, each period filled with lectures on new subjects as well as all the usual. It was a cosmopolitan group of pilots, consisting of French, Belgian, Dutch, Polish and Czechoslovak as well as English, Scots and Australian. The program was designed to cover every facet of the skills and knowledge required for proficient pilots, and also to develop understanding and awareness of the issues of the war in which the men were involved. Experts came to speak on a wide range of topics. This not only increased the pilots’ knowledge and expanded their overview, but also encouraged them to think, discuss and debate national and international affairs such as China, Japan and events in the Pacific. David relished these encounters with thinking, informed minds, these perspectives on history in the making. And he himself was asked to give a talk about Australia, which lasted one and a half hours!

More hours in the Link Trainer, and with the bombing teacher, gave further experience of instrument flying conditions that they would encounter on night operations. Climbing into the elevated cockpit, closing the hood which shut out all external light, the trainee pilot saw only the illuminated instrument panel on which he had to rely entirely. The instructor, seated below, gave directions through a voice tube. The pilot at the controls put them into practice and the Link Trainer’s simulated flying was automatically recorded on a chart on the instructor’s table, to be analysed at the end of the session.

Gunnery practice continued too, and they had their first hands-on experience with grenades, dummies to start with, from which they had to clean the mud after each session. Live ones came later. ‘At least we don’t have to clean these!’

David enjoyed going out on frosty mornings, crunching over the ice and whitened blades of grass, marching a mile to the firing range. But it was miserable on rainy days and there were plenty of them.

Distances on the station were considerable, so one evening David went looking for a bike, thrilled to know he was walking along an old Roman road, where the legions had marched so many centuries before. In contrast, medieval Cirencester’s streets were narrow and winding, but equally intriguing. Because of severe petrol rationing, bikes were in great demand and David considered himself lucky indeed to find the only one for sale. It was old and had obviously been pedalled many miles. ‘But I’ll have fun tinkering with it,’ he told himself, whistling as he rode back to the station.

In early December came the red letter day when David made his first flight in almost seven months. It was his first in England and his first in an Avro Anson. The Anson was similar to the Oxford, but with slightly less powerful engines. David had heard it described as ‘one of the most gentlemanly aeroplanes to fly, with no vices’. On this familiarisation flight as a passenger, David was immediately struck by the difference between Australian and British terrain, and noted in his diary the confusing multiplicity of detail and landmarks. And after rural Australia’s generally clear skies he found visibility much restricted by the haze and smoke from the extensive English industrial areas.

David did not enjoy occasional duties as Orderly Sergeant either, as they precluded him from flying. Inspecting huts for cleanliness and tidiness, David felt like a school prefect again.

However, he was amused to go into the airmen’s mess at lunchtime and yell out ‘Orderly Sergeant. Any complaints?’, muttering under his breath, ‘There’d better not be!’

South Cerney’s satellite base, Southrop, where David was sent, was only a few months old, a cold raw quagmire of mud and clay. The billets, asbestos huts in a winter-bare wood, were on a rise a mile and a half down dale and up hill from the flights, as aircraft dispersals and flight offices were known. So David congratulated himself on having acquired the bike. Each billet had a coal stove, but as coal was rationed they had to use it sparingly, soon finding it generated scarcely enough heat to take the penetrating chill off the perpetually damp air.

The day after they arrived at Southrop, the weather closed in with heavy mist and drizzle, so, much to the young pilots’ frustration, flying was scrubbed until the clamp lifted three days later. Over the next three months the weather would frequently make flying impossible. When winter gales, rain, snow and fog kept the planes grounded, the airmen played soccer in the mud instead. Even when the weather improved, the temporary airfield was still unserviceable, often for days.

Two days before Christmas, David made his first solo flight in England. But while he was up, a fellow pilot was killed when an engine cut out after take-off and his plane hit some trees and caught fire. That night seemed colder than ever before as David thought of the chaps in that other hut with its empty bed, and of the family somewhere for whom Christmas would never be the same again.

By now, many Australians who had survived the hazardous voyage halfway round the world and emerged unscathed from air raids, had developed an ‘It won’t

Tasmanian pilots at Southrop, 1943, L-R: Peter Lord, Ian Vickers, Gordon Lawson, David Mattingley

happen to me’ attitude. But a casualty on their own patch woke them again to the reality of their mortality. So they were determined to extract every ounce of fun out of living while they could. They threw themselves into making the most of every day. They savoured simple pleasures like sitting around the hut stove making toast or feasting when a parcel arrived from home, or enjoying local hospitality.

Once, the local doctor took David and his mates to his house, where he showed them an ancient well and a Roman wall in the garden, regaled them with tales of life as a country GP and gave them two fresh eggs each for tea, a rare treat that was double the monthly ration!

On Christmas Day, the squire made them welcome with sherry and mince pies. He was a Colonel, a contemporary of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff,

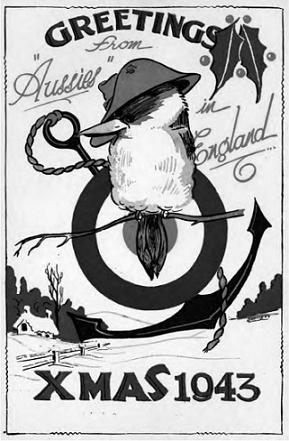

Coloured card available for Australian servicemen to buy to send home

and he entertained them with stories of the British army in pre-war India. It seemed almost too good to be true, hearing him say, ‘When I was in Poona, old chaps…’ and seeing his full dress uniform, complete with tight red tunic, striped trousers and brass hat. ‘Imagine if we had to be togged out like that!’ the boys exclaimed afterwards. David also had standing invitations from several other families, writing home, Don’t worry, Mum, there are no daughters.

Over the Christmas break, David and his friends often planned visits to the cinema or live entertainment. But the trips frequently came to nothing when the clapped-out RAF bus broke down; sometimes stranding them to walk 12 miles back to base in the wee small hours, often in rain. No wonder that they were always hungry and food parcels from home were so welcome!

Even though troops were barred from travel over the holiday season, to ease pressure on public transport, and hopes of a white Christmas were not fulfilled, it was a chance to celebrate. Contrary to station regulations, David had double-dinked a mate on his bike, and was pulled up, summoned to the Assistant Adjutant’s office.

‘Sergeant Mattingley, please explain your action,’ the WAAF officer demanded.

‘Flight Sergeant, Ma’am,’ he cheekily corrected her. ‘Just a bit of Christmas spirit.’

Interview ended!

David and the other Noncommissioned Officers (NCOs) waited on the airmen in their Mess, before enjoying their own Christmas dinner. It was a traditional meal with all the trimmings - roast pork, turkey with bread sauce, seasoning and four vegetables, followed by plum pudding with brandy sauce, and mince pies.

‘How did they conjure up all this?’ they asked in amazement, before putting on party caps and tucking in.

After carols and Christmas music on the wireless, all ranks mixed happily at a social in the Mess before returning to their huts, where partying continued as parcels from home were opened and contents shared. David’s thoughts often returned to the sunshine, blue seas and bright sands of Bridport, where his family always spent Christmas, worshipping at the little wooden church while kookaburras chortled in a nearby flowering gum ablaze with red blossom. He wrote to his parents, It was a vastly different Christmas from those I have spent in the past, but very enjoyable.

The good cheer continued for a week, as the men opened their Australian Comforts Fund hampers. David, who had just done an assignment on the French Revolution in his modern European history course, quoted Marie Antoinette, quipping, ‘Let them eat cake!’ But the allusion was lost on the others, who replied through full mouths, ‘And there’s nothing wrong with that!’ It was a bonanza - cakes, puddings, tinned peaches and cream, and chocolate - all luxuries in England where stringent food rationing affected servicemen as well as civilians. Meat, cheese, butter and milk were all rationed, as well as eggs, tea, jam, sugar, chocolate and sweets. Powdered milk, coffee and cocoa were not, honey and golden syrup were sometimes available as sweeteners, and Marmite as a spread. Vegetables were not rationed, though often in short supply. Local apples, pears, and soft fruits could sometimes be found in season, but generally fruit, especially imported, was a rarity. When given two oranges each, the men prolonged the pleasure by placing the peel on their heating stoves, to enjoy its scent before burning it for a final burst of flame and fragrance.

David was overwhelmed by the kindness of the many people who sent him parcels, and he always saved some of the contents to give to the people who showed him hospitality. The Christmas parcel from his parents contained nuts, raisins, tinned jam - apricot was always a favourite on toast at night - chocolate, his mother’s incomparable cake and pudding. The parcel also included some newspapers, which the boys eagerly passed round, frequently exclaiming ‘Look at this!’ and ‘What do you know!’ as they found hometown news items.

Despite his mother’s skill in packing, once a packet of soap flakes burst, impregnating the adjacent chocolate. They devoured it nevertheless, as the ration, only four ounces a week, was rarely available. Another time, vinegar from a jar of onions, pickled specially for him, leaked into the chocolate. David wolfed it down anyway. By the time a parcel posted in mid-August arrived in March, the coconut ice had to be broken with a hammer! But it was a welcome addition to the weekly six-pennyworth allowance of sweets. In another batch of parcels, a cake arrived without even a crack in the icing. Once, when four parcels arrived together, he saved a round tin till last, expecting it to contain a cake. Instead he found several pairs of socks and a scarf!

In contrast to Christmas, New Year’s Eve was very low key, and the men were subdued, wondering what 1944 held in store. Only a few more months of training remained before they would be dispersed to start flying operations. Then they would join the war in earnest.

But for David the ecstasy was the flying. The very heart of it. He loved the hours riding the air, looking down on the patchwork English countryside and all its landmarks, or the snow-white tops of fleecy clouds billowing up below. But in January they saw the sun only once in three weeks and the unrelenting grey was dreary indeed. Instead of being skybound, they were earthbound in mud and slush, and they were really browned off. David watched enviously as squadrons of rooks from nearby woods soared and circled in faultless formation against the sombre sky. ‘Showing off their superior flying skills!’ he exclaimed in admiration.

When fog, worsened by industrial haze, enveloped the whole area the men were given leave. David went to Brighton looking for his recently arrived old school friend, level-headed Des Hadden, whose wry sense of humour matched David’s own. It was great to laugh over old times and swap stories of all they had seen and done since they last met seven months earlier in Melbourne. Well worth the ten hours travelling each way, some of it standing in the crowded trains, and the wet five-mile walk to base.

Another 48 hour leave pass was a great boost to morale. David and fellow Tasmanian Gordon Lawson, a likeable larrikin, headed for their customary rendezvous, the Boomerang Club, where David ordered his favourite curried sausages. But he got more than he bargained for when someone accidentally tipped a plateful down his uniform!

‘I wish I’d thought of doing that!’ Gordon grinned as he helped mop up.

Later, they looked in the visitors’ book as usual, and enjoyed catching up with fellows they had known on other courses.

Next day, a notorious London pea soup fog disrupted rail services, then an air raid further delayed their departure. So their train was two and a half hours late. Standing in the guard’s van, David made the better acquaintance of Peter’s flying instructor, English Sergeant Sam Salter. He was delighted to find they were on the same wavelength, Sam’s quirky humour and way with words instantly appealing to him. But at Southrop they were annoyed to find that because the usual fog prevailed, there was still no flying.

‘Why the dickens didn’t they let us stay on leave?’ everyone grumbled.

After four more frustrating days grounded, they were again given leave and headed immediately for London. In retaliation for 2300 tons of bombs dropped on Berlin by the RAF the previous night, German fast raiders came over, dropping bombs a few hundred yards from Victoria Station, where David was staying. Several German planes caught in the searchlight were downed by anti-aircraft guns. Their shrapnel fell like rain. During a second raid at 4 am, David pulled back the blackout curtain to watch the dramatic scene. He knew he was one of the actors waiting in the wings for similar action somewhere over Europe. Soon.

The next day they returned to base, cycling the last five miles in heavy rain, only to find that they had been given another two days leave. Everyone was really cheesed off.

‘Bloody hell! We stood all the way on the trains from London for nothing again!’

So it was back to London, arriving at midnight, with the chance to see another national treasure next day, the vessel Discovery, of famous Antarctic explorer Captain Scott, one of David’s heroes.

Back at Southrop, it was more of the same. At two hours notice, the men were given five days of leave. David was both disappointed and pleased. Disappointed because it was 25 days since he had flown and he longed to be in the air again. Pleased at another opportunity to fulfil his other passion - exploring Britain.

This time David went north. Baby-faced, open-hearted Scots pilot David McNeill, whose wisdom was far beyond his short stature and nineteen years, had become one of David’s best friends on the station and had invited him home. The two Davids had to go to London and wait till 4.15 next morning for the train to Edinburgh. David found plenty to interest him on the long journey north. The Yorkshire moors were thick with airfields, and at Newcastle he was thrilled to see one of George Stephenson’s early locomotives. Then crossing the wide River Tweed, he had his first sight of bonnie Scotland. From Edinburgh they caught a bus to Tranent, a small mining town, where the McNeills lived in a council house.

David was deeply touched by the warm welcome offered by yet another kindly family, who promptly named him Dights, to avoid confusing two Davids. Mr McNeill, a miner retired after a back injury, was now a school caretaker. Mrs McNeill, a great cook, was devoted to looking after her husband and their four children. Learning of David’s interest in education, Mr McNeill showed him over the school where he worked. The headmaster explained the impressive Scottish education system and invited David to speak about Australia to two classes.

David McN took his Australian namesake touring the district, so rich in history. In the village of Prestonpans, scene of the Scots victory over the English in 1745, they

David McNeill, Pilot, with the family dog, Judy, Tranent, Scotland

had a drink at the Cross Keys pub where Bonnie Prince Charlie had stayed on the eve of the battle. But the battlefield itself was covered in slag heaps and could no longer be seen.

David found Edinburgh most attractive of all the British cities and towns he had seen, with its wide streets, beautiful gardens and gracious stone buildings, all guarded by the great castle on its rocky eminence. Watching a game between crack Scottish soccer teams was another highlight, standing shoulder to tweed-coated shoulder with passionate barrackers shouting themselves hoarse.

After divine service in the wee kirk where Bonnie Prince Charlie had worshipped, Sunday was a relaxing home and family day. The pleasure of walking the dog was followed by a memorable dinner, and visits to relatives and friends who delighted in recounting tales of the past.

On the way south, the Davids congratulated each other on finding seats on the crowded Flying Scotsman. ‘Glad we don’t have to stand overnight for ten and a half hours back to London.’ After several changes of train and the final bike ride, they arrived at Southrop in the early hours.

‘We’ve burned the candle at both ends,’ Dights said to Scottish David, ‘but it was worth it. The Scots are the most generous and kind-hearted folk I’ve ever met. And they make the best cakes! And the best porridge of course!’

In February 1944 the British winter was at its worst. January’s rain had turned to sleet. Sleet turned to snow. Snow melted to slush. Slush froze into solid chocolate chunks. Gales uprooted trees. And the cloud ceiling came down lower and lower. Flying was out of the question on most days. The trainee pilots, eager to get their flying hours up, sat disconsolate around a huge fire in the mess. Or huddled in their huts, wearing their sheepskin jackets, scarves, mittens and anything else they could put on in an effort to defy the cheek-tingling, finger-numbing, bone-chilling cold.

On one unnerving cross-country flight, David became lost. The strengthening wind had changed direction. Visibility decreased and he found himself badly off course. In sight of the south coast, with dwindling fuel supply, he made for an airfield in the distance. His radio was not on its frequency. But the weather was clamping down, so he landed regardless. Because its aircraft were returning from a mission, landing at much higher speeds, he had to touch down and clear the runway quickly.

It was Dunsfold, an operational station, near Guildford in Surrey, base for one Netherlands and two RAF squadrons. Snow and sleet kept David grounded for the next five days, but he relished the opportunity to absorb the atmosphere and experiences of an operational station, so different from a training station. He also inspected the different kites: Mitchells, flown by the squadrons, and a Beaufighter and a Lancaster which had also landed because of bad conditions. He spent time in the control tower, listening to radio telephone conversations from planes on operations. He heard two distress calls, the chilling ‘Mayday, Mayday!’ received on Darky, the emergency frequency, and he shared the general elation when both planes were successfully brought home. It was stirring, too, to watch the squadrons set off before dawn on a tactical sortie and return from France after sunrise.

Back at Southrop, where the countryside was quilted in dazzling white, the trainees had bags of fun in the snow, and two Wellingtons and a Spitfire, which landed because of sleet and icing, attracted a lot of attention. When flying was scrubbed David swotted for exams.

Late in February it was time for another move. The men were sent to a specialised course at Lulsgate Bottom in Somerset.

‘Ee, lads,’ David mimicked the Somerset accent, ‘we be goan to Zummerzet where the zoider apples grow!’

BAT Flight instruction, apt acronym for Beam Approach Training, initiated pilots into the system developed to enable planes to land in all weathers. But on the first morning they could not take off because of the weather!

On his first flight, still in the dependable Oxford, David climbed through 5000 feet of cloud and encountered icing for the first time. Thick rime coated the leading edges of the wings. Lumps of ice were flung off the propellers onto the fuselage. The controls became very stiff, and the aircraft became noticeably sluggish. He realised how important and useful it was to experience such an unnerving condition. Real operations were flown at higher altitudes, so David knew he would encounter more icing on bombing runs.

On a dull day, with the aid of the Beam, he climbed through the low cloud ceiling to a wizard new world of warm sun shining brilliantly on the fleecy clouds below. On another flight he landed, again with the aid of the Beam, at Hullavington, the Empire Central Flying School for training instructors, in Air Force slang the home of gen, or genuine information. Here, of course, it was all ‘pukka’ not ‘duff’ gen. He saw an amazing array of aircraft, including Magisters, Masters, Bostons, Wellingtons and mighty Stirlings, Halifaxes and Lancasters. And realised yet again how much there was to learn about flying.

David had not seen his brother Brian since leaving Australia ten months earlier. Brian was now an RAAF navigator, and the twenty-three hours David spent in Brighton was hardly long enough to catch up on news of family, friends and acquaintances.

‘How are Mum and Dad? I’m afraid they might be depriving themselves of hard-to-get or rationed items, so as to include them in my parcels.’

‘Don’t worry. Dad is getting a real kick out of finding things for you. I must say those packages look pretty awkward to sew up. But you know how good Mum is with her needle, and it means a lot to her to be doing it for you,’ Brian reassured David. ‘You’ve got quite a fan club at home! The Misses Campbell are knitting socks for you. Mr Ingles the grocer has sent you a tin of sugar, even though it’s rationed at home too. And the baker has made you a special cake.’‘What about Max?’ David wanted to know.

Brian laughed. ‘Last time he was home on leave he was mistaken for the Russian Consul at a special service at St John’s. Because of his beard!’

David chortled. He could tease his Senior Service brother about that!

‘How was your nav course?’ he enquired.

‘Mt Gambier? Spot on. A good bunch of chaps.’

David hesitated. What he had to say next was awkward. ‘I hope you will understand if we happen to be together on the next course and I don’t ask you to be my navigator. Too many eggs in one basket.’

Brian nodded soberly. One telegram from the War Office would be bad enough. Two from the same op would be too terrible for their parents. ‘Of course. But you should look out for a chap named Reg Murr. We came over on the same ship. He’s a bit older than me. Seemed very reliable. Genuine. He could be the nav you want.’

On that trip, David also hoped to see Des Hadden. He envied Des’s posting to an Advanced Flying Unit at the King’s private airfield, irreverently dubbed Smith’s Lawn, in Windsor Great Park. Especially when he heard the airmen were given a tour of Windsor Castle. But for now it was back to Lulsgate Bottom.

At the end of the course, the pilots returned to Southrop for the challenge of night flying. They chafed and grumbled as weather conditions again curtailed or scrubbed their exercises of beacon stooging and circuits and bumps. Fog still obliterated visibility and rain washed out the airfield. But lectures and progress checks continued. One pilot’s training came to an abrupt halt when the controls locked during a test flight and his plane pranged on a concrete pillbox. He was lucky to survive but he had two broken legs. ‘He almost went for a burton,’ they said in the Mess.

Later, another pilot’s flying career ended in a particularly grisly manner. As he put on his parachute harness, the propeller struck his arm and severed it. David pitied the men who had to pick up the arm and take it to the Flight Commander’s office.

Just when the weather cleared, flying was suspended again - this time for an exercise by units of Transport Command. Troop transport Dakotas and glider tugs flew over, releasing 38 Horsa gliders, designed to be used for invasion, each capable of carrying troops, a jeep, motor bikes or a 75 mm gun. David wrote, It was wonderful watching a sight which people of occupied countries will see in the near future. He wondered how near that future was. Weeks? Months?

Whenever the clamp lifted and the weather held good, he noted with satisfaction, We are getting bags of hours. But cross-country flying at night was even more challenging, with constant hazards of high tension lines, as well as wooded hilly terrain. When night flying was suspended as unsafe with Dakotas, Stirlings and Horsas stooging over from two newly opened bases nearby, daylight cross-country flights were reintroduced. Eastward flights revealed many operational airfields, with longer sealed runways for heavy bomber use, in contrast to the smaller grass training airfields such as Southrop, mainly in the west. Formation flying also returned to the program.

With spring in the air, romances began to blossom and one lad became engaged to a girl from Brighton. But David still had only one love - flying. He and David McNeill took advantage of double summertime evenings to explore; cycling through the countryside, admiring picturesque villages and bridges, revelling in signs of their first English spring. Tiny buds appeared on bare trees, which gradually turned to shimmering green. Waves of bluebells flooded the woods. And on a Sunday leave in Oxford late in March they delighted in the brilliant swathes of crocuses under the trees in the University Gardens.

On another trip to Oxford, while they were staying in a dormitory, several servicemen stumbled in late, much the worse for wear. In the morning, David’s acquaintance Jim got up and shouted, ‘Who’s been pissing in my shoe?’, adding expletives not usually heard from the son of a bishop.

‘Well, I hope he’s a bomb aimer or a gunner. He was spot on target!’ laughed David from his bunk. He observed that thereafter one of Jim’s shoes was noticeably duller.

Longer leave allowed the two Davids to return to Scotland for Easter, where Dights was again welcomed warmly into the McNeill family, plied with good home cooking and introduced to a poacher who specialised in salmon. At a woollen mill famous for Border tweeds, David used most of his clothing coupons to buy a length for his mother. Then an unwelcome telegram, unexpected on Good Friday, recalled him to Southrop. It was time to move on yet again.

Easter Monday was occupied by the tedious task of trekking all over the station to obtain clearances, and packing up. You’ve no idea how hard it is trying to get all one’s accumulated junk plus ordinary gear into a couple of kitbags, David wrote home. He went into Cirencester with friends, regretting that this would be the last time. He had become very fond of the interesting old town and of the Cotswolds. It was also time to say goodbye to mates who were going on to different destinations. The severing cut more deeply than ever before, as Ian and Gordon were posted to Cairo, and David McNeill, who had become his closest friend, was to be sent to the Middle East. David and Peter were grateful they were going on together.