The trains taking David and Peter north to their next posting at Lichfield in Staffordshire passed through lush pasturelands and orchards bright with blossom. At No. 27 Operational Training Unit they would be introduced to their first heavy bomber, the Wellington, dubbed Wimpey, or as David described it to beat the censor in his letters home, The Iron Duke.

Lichfield was also a permanent station, the biggest they had been on so far, requiring Service Police to direct traffic at rush periods. For two weeks the pilots enjoyed comfortable quarters while they did an intensive Wellington theory course and inspected the planes on the ground. The lecturers were experienced airmen who had completed a tour of operations and, transferred to other duties, were said to be ‘resting’. Most had ‘gongs’, which impressed David. Lectures started at 8 am and finished at

Vickers Armstrong Wellington, or ‘Wimpey’, David (centre) with Noel Ferguson (L), Drew Fisher (R), at Church Broughton, 1944

6.30 pm, even on Sundays after church parade. Physical training was held every second evening.

Now, as well as learning about the biggest aircraft they had yet flown, there was an enormous added pressure on the pilots. At Lichfield, men from all musterings were thrown together, and on the fifth day ‘crewing up’ was to take place. Each pilot had to select the men who would form his crew. At 21, David had to make the most important choices of his life so far. For the first few days the pilots moved around the intake of other musterings, talking to navigators, wireless operators, gunners and bomb aimers; observing; quietly assessing personalities and potential. Each pilot was aware of the long-term implications of his choices - it could be a matter of life or death. It was essential for crew members to be compatible, to be able to work as a team under the most demanding conditions. Two nights before making his selection, David took a long, reflective bike ride, to ponder his choices.

On the morning of Monday 17 April 1944, the aircrew of No. 27 OTU, predominantly Australians, gathered in an empty, echoing hangar. They tended to cluster with others from their own mustering, some stamping their feet on the cold concrete, staring absently into space; others talking desultorily, whistling or humming under their breath. Some were relaxed, some confident, others clearly a little apprehensive.

‘It’s like a cattle market,’ one chap quipped.

‘A slave market, you mean,’ corrected another.

Meanwhile, the pilots strolled from group to group, speaking with individuals. Everyone wanted to be chosen by a pukka skipper. It was like being back at school, waiting to be picked for a team in a lunchtime game. No one wanted to be left to the last. But this was no game.

A good navigator was crucial for successful operations and David already had his eye on the one he wanted. Reg Murr had travelled to Britain with David’s brother Brian, and David approached him first. He was 35, older than most, and married. David thought his maturity would complement youthful impetuosity in others.

‘Have you been asked to join a crew yet?’ he enquired of the Queenslander, who was pale-faced like all the others after the long sunless winter. Reg, a silent type, shook his head. ‘Would you like to fly with me?’

Reg nodded. He too had been observing.

‘Think it over,’ David suggested, ‘and meet me in an hour’s time by the hangar door if you’re still on.’

Looking at brevets which denoted flying qualifications, David approached a bomb aimer he had already singled out: Drew Fisher, another Queenslander, also married. He introduced himself. ‘Would you like to serve with me?’

Drew beamed. ‘Sure would,’ he replied, and added jokingly, ‘I thought you’d never ask!’

David again went for maturity in his choice of wireless operator: 27-year-old Sydneysider Reg Watson. But he chose two gunners for their youthful alertness. Both were short, which meant they would fit more readily into their turrets, so cramped after many hours on a long op. Both were from Newcastle, New South Wales. 19-year-old Noel Ferguson had suggested 18-year-old Allan Avery, with whom he had trained, and David trusted his judgment. The original groups were dispersing and re-forming in small clusters around pilots. It was a momentous day in all their lives.

Reg Murr (Murga), Navigator; Noel Ferguson (Boz), Mid Upper Gunner; Allan Avery (Birdy), Rear Gunner (photo taken 1951)

As David’s new crew gathered by the hangar door, Drew was the first to speak, ‘I reckon we’ve got ourselves a gen skipper!’

Reg Watson agreed. ‘He won’t be flying just by the seat of his pants. Did you notice how he concentrated in those early lectures?’

Reg Murr nodded.

Allan burst out, ‘I was hoping he’d pick me.’

‘Allan and I wanted to stick together,’ Noel added, ‘and Skipper took my advice.’

They all looked at one another and the tension of the morning began to melt away. It boded well for a crew when the skipper was prepared to listen to their opinions.

David was pleased to see all the crew he had chosen waiting together for him by the hangar door. ‘Let’s eat together at lunch,’ he suggested, keen to begin their bonding.

That night he wrote in his diary: I have now decided on our crew, and listed them by name, state and function.

Some of the gen crew: L-R: David, Reg Murr (Murga), Allan Avery (Birdy), Reg Watson (Pop), Drew Fisher, Church Broughton, 1944

Three have a good deal of experience, while the gunners are young and keen, so we shall make a gen crew when training is finished.

David also made it his business to study all the aircraft on the busy station - Halifaxes, Coastal Command Liberators and Fortresses, as well as Typhoons, Hellcats, Hurricanes, Kittyhawks and Martinets. In the second week, in addition to the usual airmanship, armaments and signals, there were lectures again on intelligence, with gen on escaping from German and enemy-occupied territory. There were also further practical sessions on ditching procedures and dinghy drill appropriate to the Wellington. The men were issued with extra flying kit - wool and rayon underwear for high altitudes and a whistle for blowing in case they were unlucky enough to end up in the drink. With so many possibilities in mind, it was heartening to see a Liberator make a perfect landing on only three engines.

After eleven days of study, three solid days of exams, and a rigorous PT test, David and his crew spent some welcome leave together to continue their bonding. Then it was time to make their seventh move in under eight months.

A beautiful drive through cloth-of-gold countryside shining with buttercups brought them to another satellite airfield, Church Broughton in Derbyshire. Everyone was delighted with the new billets; modern Nissen huts, set among fine old oak and chestnut trees in full spring glory, the ground carpeted with grass and wildflowers. After Southrop’s mud it seemed like paradise.

But, best of all, it was back to flying!

The Wellington, designed for operations, was very different from the Oxford, which was mainly a trainer. Bigger, heavier, with considerably more powerful engines, it was almost twice as long, two thirds as high again, with a vastly increased wingspan and area, as well as greater maximum speed and range. David described the Wimpey as ‘sturdy and reliable, although very heavy on the controls.’

Familiarisation flights were done with a screened pilot, one who had completed a tour of operations and was resting, although going up with sprogs, as new pilots were known, could not always have been restful. The sprog had to get used to the controls, putting into practice what he had learnt in lectures, going through the actions and manoeuvres already learnt on Tiger Moths and Oxfords. Skill and speed were critical and could mean the difference between escape and being shot down by an enemy fighter. As well as the highly necessary take-offs, circuits and landings routines, popularly called bumps, David learned to put the Wimpey into steep turns and corkscrews for evasive action, and how to handle the plane with only one engine and feather a propeller to control unwanted rotation.

The crew went back to Lichfield for a ‘grope’, as a synthetic bombing trip was named. It was a five-hour simulated exercise through flak and searchlights, designed as an introduction to the real thing, particularly requiring the navigator and wireless operator to show their skills.

David continued to work in the Link Trainer. Then, flying solo, he took the crew up, stooging around at 4000 feet to give them the opportunity to get used to the aircraft. There were cross-country flights for the navigator, practice on the Gee radar for him, the wireless operator and the bomb aimer, and for the gunners exercises with dummy attacks by Martinets representing enemy fighters. These were carried out with a cine-gun, which filmed the action for later study, identifying errors to be rectified. For the bomb aimer there were runs over bombing ranges, dropping sticks of practice bombs and observing their accuracy.

Everyone was enjoying the milder weather, but the warmth brought its own problems, principally poor visibility on account of the industrial haze. Flying was still sometimes cancelled.

David seized every opportunity to develop the camaraderie so vital for good crew morale. When they had time off they caught local buses or hitchhiked, exploring Derby with its big Rolls Royce plant, now switched from making luxury cars to aircraft engines, Nottingham once renowned for lace, now for Trent Bridge cricket ground, and Burton-on-Trent, famous for its breweries. They were intrigued, too, to pass through the village of Melbourne. Nothing like the Melbourne we know, David commented to his parents.

They also enjoyed bike rides in the long summer evenings. They discovered stately homes, ancient churches, Elizabethan manor houses, and quaintly named old pubs, such as The Saltbox, which they nicknamed The Pepperpot. David was pleased to show some of these places to Brian, now posted to Church Broughton too.

One night cycling back, they overtook another pilot who was decidedly under the weather. Weaving his way along the towpath, he overbalanced and toppled into the canal. Water streaming from clothes and hair, he emerged moaning, ‘Oh, my profile! Oh, my profile!’, much to the crew’s amusement. It became their private joke, whenever they were laughing their way through a trying situation, for someone to exclaim, ‘Oh, my profile!’

On glorious summer days, their Australian issue shorts and shirts were the envy of British crews, chafing hot in their woollen jackets and trousers. They spent many afternoons by the delightful Dove River, swimming and lying lazily on the grass in the sun, chatting, chiacking, telling their stories and getting to know each other.

Reg M was a man of few words, but when they came they were always worth listening to. Observant and thoughtful, he watched the others with a quiet, almost avuncular smile, and they affectionately named him Murga, short for Murgatroyd.

Reg W, an accountant before the war, who sported a dapper moustache, was as precise in manner and speech

David and Drew outside their Nissen hut, Church Broughton

as he had been with columns of figures. He had a lively side too which made for interesting exchanges and earned him the nickname Pop.

Drew, a primary school teacher, had a quick wit and they all encouraged his quirky repartee.

Nuggety Noel, already known as Boz, had an engaging boyish grin. The shortest in the crew, his arms always seemed to be folded firmly across his chest, as if to say, ‘I may be small, but take me on! You just try it!’

Also short, solid and athletic, was Allan, whom they named Birdy. He was a bit of a larrikin, with a mischievous lopsided grin. The youngest in the crew, his old face seemed to indicate more experience than his eighteen years.

David was well pleased. They were a good bunch. Not a clot among them. None was a heavy smoker and all were only light drinkers. It augured well for ops.

In addition to getting to know each man as an individual, it was just as important for David to become fully conversant with the duties of each crew member. He attended the gunners’ aircraft recognition lectures, to keep himself up-to-date. He spent a morning in the wireless section with Reg W, and time in an aircraft where Reg showed him how to work all his equipment. He gave Drew instructions on the Link Trainer, to help ensure the critical accuracy needed in bomb aiming.

He also took close note of excellent airmanship and any unusual kites. He watched an Albemarle come in with an engine on fire, and was thrilled to see a new Spitfire Mark XIV land, and later do a remarkable steep climbing turn after take-off. He inspected a Fortress whose internal layout catered better for the crew than the Wellington. ‘But,’ he declared, ‘performances cannot be compared, British aircraft being well in the lead.’ He had been observing test pilots on highly secret experiments in jet propulsion and was very impressed with two Wellingtons modified for jets, and two twin jet fighters, known as squirts, whose speed was well in excess of 500 miles per hour. He wrote in his diary with satisfaction, Squirts should be able to make things somewhat unpleasant for Jerry.

David’s knowledge of Britain’s geography and topography was also increasing steadily, as cross-country flights extended to four hours and more. Seeing Wales, the Isle of Man, Scotland and Eire, all on one flight, was memorable. A lecture on German night defence had crews on the edge of their seats, listening intently to information about the elaborate and effective system of controlled interception by night fighters and cooperation with searchlights and flak batteries. David, who already spent many hours in the intelligence library, encouraged his crew to do likewise. A lecture by an RAF official interrogator describing how much gen can be given away by apparently harmless remarks by POWs, quoting German airmen he had questioned, was also very sobering.

At the beginning of June night flying began again. After his first flight David wrote in his diary, The circuits and bumps certainly make one sweat in a Wimpey. They were hard work. But night flying also brought the benefit of sleeping in, and much appreciated extra rations. The rigorous mental training plus strenuous physical demands meant the men were always hungry, looking for a feed, calling at farmhouses hoping to buy eggs. Parcels from home, shared among the crew, continued to supplement rather basic meals in the Mess. Everyone contributed what they could for a feast in the hut for the skipper’s 22nd birthday, and Drew ribbed David, ‘Any tip left under the plate will be gratefully received.’

They made their first night cross-country with a screened pilot, who left them to their own resources, pleased at how well the crew worked as a team. On their second, aware that Reg W had gone to relieve himself, David deliberately put the aircraft into some sharp manoeuvres. He didn’t know that the Elsan, the small portable toilet, had not been emptied from the previous flight. Reg copped the lot and was not impressed, though the others enjoyed the prank.

For a change, flying conditions were excellent, with clear starry nights and a young moon. One evening the crew were fascinated by a display of Aurora Borealis, the Northern Lights. On a non-flying night Reg W was tempted to sleep under an oak tree, but found that caterpillars falling on the bed kept him awake. ‘First it was crap, now it’s caterpillars!’ he grumbled.

At the night-flying briefing on 5 June, the men were warned to be careful of large numbers of gliders on an operation, and next morning they woke to the announcement of D-Day, the opening of the Second Front with the landing of Allied troops in Normandy. Reports that the invasion was going well led David to write in his diary, So let us hope the European war will be over within a year.

Training flights were temporarily transferred to Lichfield, as Church Broughton was in heavy use by operational aircraft. David was chuffed to see a naval fighter Fairey Firefly, still on the secret list, impressed by its short take-off and very tight manoeuvres.

Fighter affiliation, when friendly fighters took the role of attacking aircraft, was another exercise designed to improve crew responses and give them a taste of what was to come. So was a session in a mobile decompression chamber, from which the air was slowly pumped, allowing crews to experience the effects of oxygen lack at altitude. All wore oxygen masks and headsets, but when one took his off at 25 000 feet he passed out. His speedy recovery when others replaced the mask for him was convincing proof of the purpose and necessity of wearing the gear. Another who wore no mask lasted until 23 000 feet, but his writing became illegible and his calculations inaccurate. It was a telling lesson.

A ‘bullseye’ exercise involving both night fighters and searchlights on a cross-country was designed to develop crew cooperation. The gunners acquitted themselves well and David was pleased he evaded all searchlights. The final exercise in operational training was a bombing run.

The weather, night flying and gruelling cross-country flights in obsolescent aircraft led to a high accident rate. Almost one thousand Australian aircrew were killed or injured at Operational Training Units. So everyone was chuffed when the course concluded without any casualties.

‘Good show, chaps!’ the CO declared. ‘You’re the best lot to go through this OTU.’

In the last week of training, David had three successful interviews for a commission. Now I’m waiting for the paperwork to come through, he wrote home. In his diary he wrote I have enjoyed it. Church Broughton is definitely the best station on which I have been. But he was tired and had lost 22 pounds in weight over the ten months in England. The strain of flying and the heavy study program had taken their toll. He was glad that after the usual time-consuming task of obtaining clearances, in the rain as always, the men were granted leave - eight whole unprogrammed days for fun and relaxation. David and two friends from another crew headed for the Lake District.

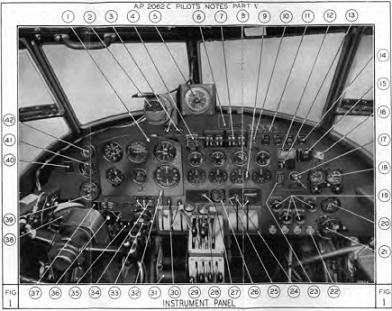

KEY TO Fig. 1

INSTRUMENT PANEL

1. Instrument flying panel.

2. D.F. Indicator.

3. Landing light switches.

4. Undercarriage indicator switch.

5. D.R. compass repeater.

6. D- R. compass deviation card holder.

7. Ignition switches.

8. Boost gauges.

9. R.p.m. indicators.

10. Rooster coil switch.

11. Slow-running cut-out switches.

12. I.F.F. detonator buttons.

13. I.F.F. switch.

14. Engine starter switches.

15. Bomb containers jettison button, if). Bomb jettison control.

17. Vacuum change-over cock.

18. Oxygen regulator.

19. Feathering buttons.

20. Triple pressure gauge.

21. Signalling switchbox (identification lamps).

22. vire-extinguisher pushbuttons.

23. Suction gauge.

24. Starboard master engine cocks.

25. Supercharger gear change control panel.

26. Flaps position indicator.

27. Flaps position indicator switch.

28. Throttle levers.

29. Propeller speed control levers.

30. Port master engine cocks.

31. Rudder pedal.

32. Boosr control cut-out.

33. Signalling svvitchbox (recognition lights).

34. Identification lights colour selector switches.

35. D.R. compass switches.

36. Autw controls steering lever.

37. P.4. compass deviation cardholder.

38. P.4 compass.

39. Undercarriage position indicator.

40. A.S.I, correction card hold.

41. Beam approach indicator.

42. Watch holder.