TheLake District is a land somehow apart, reminding one of A Midsummer Night’s Dream or some similar fantasy, David wrote to his parents. Five idyllic days quickly passed. Walking, climbing, rowing, swimming nude in secluded bays, breathing the soft, clear air, the young airmen were refreshed and reinvigorated in body, mind and spirit by nature and the magnificent scenery. It was too late for the daffodils immortalised by Wordsworth, but David revelled in discovering other associations with both poets Wordsworth and Coleridge, and novelist Hugh Walpole. He had been having difficulty filling a weekly one page airgraph to his parents, as so much about life on an RAF station could not be mentioned. But now he had something to write about, and happily filled eight pages, reporting to his mother that despite all the exercise in those five days he had put on five pounds!

Lancaster main instrument panel

After a pilgrimage to historic York, David caught another train to Doncaster in Yorkshire to meet his crew again and go on to No. 1656 Heavy Conversion Unit, Lindholme. Here, pilots learned to fly Halifaxes, four-engined planes much bigger than the twin-engined Wellingtons, with longer range and increased bomb capacity. The controversial Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, Commander in Chief of Bomber Command, widely known as ‘Bomber’ Harris, was convinced that Germany could be defeated by air power, with strategic bombing to destroy military infrastructure and demoralise civilians. In order to carry out his strategy of mounting 1000 bomber raids over Germany he sometimes used aircraft and crew from these training units. To aircrew who bore the brunt of these operations, he was ‘Butcher’ or ‘Butch’ Harris. And David and his crew were aware that, although technically still in training, they might be called any time for an operation. The war was very close now.

The men were issued with more flying kit, including silk gloves and woollen mittens to be worn under leather gauntlets, and began lectures immediately. These covered tactics, enemy anti-aircraft measures, medical aspects of flying and vital survival equipment, parachutes, and Mae West life jackets, with further wet cold dinghy drill. PT featured heavily in the program, and a route march, never appreciated, brought home the point of the nursery rhyme. The grand old Duke of York, He had ten thousand men, He marched them up to the top of the hill, And he marched them down again.

David and two others, sent off to do another short course at No. 1 Engine Control Demonstration Unit, had to stand all the way to London, four hours on a packed train in hot muggy weather. The men had been shown a film on the latest Nazi weapon, V1, the dreaded flying bomb, whose speed and unpredictable fall made it very hard to intercept. When David and his companions arrived in London to find a V1 attack in progress they were very glad to catch another train on to their destination. David again came across people he had known on earlier courses, eagerly swapping stories and enquiring for news of others with whom he had lost touch. Four solid days of lectures and practical work on the latest Rolls Royce Merlin engines were relieved by a light-hearted evening on the dodgems at the local fair. After a three-hour exam on the fifth day, it was back to London.

Here the effects of the flying bomb attacks were immediately apparent. Streets were deserted. Many servicemen were now in France and many civilians, especially women and children, had been evacuated to the country, as they were during the Blitz. David was shocked to find that all the glass in Australia House had been blown out, and the noise of the bomb engines and sirens kept him awake most of the night. Standing on another crowded train for nearly five hours they returned to Doncaster.

Then, in the last week of July, the men had to pack up again to transfer from the reception depot to the main camp at Lindholme, a peacetime station with more comfortable quarters. David was very pleased to welcome their flight engineer and introduce him to the rest of the crew. Nineteen-year-old fair-haired Cyril Bailey from Kent was the only Englishman among them.

‘An English rose among blue orchids,’ they joked.

‘Don’t you mean colonial thorns?’ he retaliated, and the bond was cemented.

Cyril Bailey, Flight Engineer, at home, Birchington, Kent

The course began with a general lecture series that everyone attended before each crew member went to his own specialised section. Sessions on engines, navigation, gunnery and the mechanisms of various gun turrets, evasion and escape tactics filled many hours, both day and evening. They were shown over a Halifax to learn its layout, and spent time in the spotlight trainer, a gun turret sighted on to aircraft projected by film onto a large dome, which David found good practice in sighting and manipulation. They also watched a film about radar, the Y or H2S. This device, which enabled an image of a town, river, lake or coastline to be picked up and shown on a screen in the aircraft, together with bearing and distance, had already proved its value in operations.

On the long summer evenings the crew cycled between fields of golden grain splashed with red poppies. A visit to a village named Spittle-in-Street evoked some joking. ‘How unhygienic! Not a desirable address!’

David was annoyed when his bike was stolen, putting an end to jaunting. He wrote to his parents, News is scarcer than ever, as I have not been out for ten days. Somebody stole, pinched, swiped, thieved, misappropriated, confiscated or otherwise feloniously removed my bike.

Early in August they had their familiarisation flight in a Halifax. In good hands the Hali flies well, except that it is heavy on the aileron controls, David commented. Later, at the controls himself, he found he had to work hard doing circuits and bumps. Twenty feet high, with a 100-foot wingspan and four engines, The Hali is distinctly different from any other aircraft I have flown, he declared. When he started to fly solo at night, he was very glad to have Cyril standing beside him, assisting with the four throttles. He wrote in his diary, The engineer is an invaluable aid - in fact a necessity - for taking off and landing. Later, on a cross-country in an aircraft with dual control, he took the opportunity to teach Cyril some flying skills.

As ever, training was often interrupted, not only by rain and fog, but because early Mark II Halifaxes were discards from operations because of age or damage. They frequently became unserviceable. ‘Hallibags! Clapped out old kites!’ the crew grumbled. A bombing exercise was aborted when the sight became u/s. Circuit practice had to be discontinued because of a flat tyre. A cross-country flight had to be abandoned when a broken pipe poured oil onto the hot exhaust. David feathered the propeller and turned back to base, only to find that another aircraft had pranged on the Lindholme runway. They were diverted to nearby Sandtoft, which had earned the unenviable nickname Prangtoft, and landed on three engines. The crew’s confidence in their skipper, already considerable, increased further. After another training flight the crew were in the transport on their way back when Pop suddenly exclaimed, ‘Where’s Boz?’

They returned at once to the aircraft to find Boz asleep in his turret!

‘That’s a tribute to your landing skills, Skip!’ the crew laughed.

But David’s awareness of their mortality, already considerable, had also increased. In July, just two months before David was to go on operations, the war had struck deeper than ever into his heart. He learned from his parents that his cousin Frank, a gunner in 463 Squadron RAAF, was missing on a raid over Germany. He and Frank had met only once because Frank lived in Western Australia. But Frank had trained at Western Junction after him. They had been looking forward to meeting and had been exchanging letters in anticipation. Frank had been in Lincolnshire for a week when he wrote in May, As you can see, I’m just about in the war now. No ops until last night when the skipper went on a second dickey. We should be off next time, I guess.

They were. And they did not return. Posted MISSING.

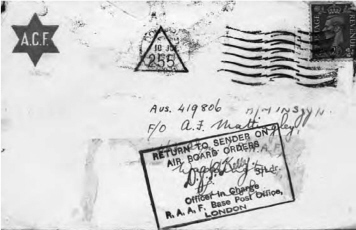

But a letter David had written to Frank did return. Unopened. Stamped in purple: RETURN TO SENDER ON AIR BOARD ORDERS.

He cringed as he re-read what he had written when unaware that Frank had gone missing six weeks earlier on his first op. How are you enjoying life with 463? Apparently they work you fairly hard these days, so you should get through your tour quickly…If you want a quiet leave, the Lake District is to be recommended.

Frank would never get through his tour. He had barely begun it. He would never know the delights and serene beauty of the Lake District. What were his last moments? What horrors did he see? What did he know? What were his feelings?

David’s last letter to his cousin Frank Mattingley

Frank Mattingley, Gunner, killed aged 21, over Handerath,Germany, 22 May 1944, on his first operation

Frozen with pain, David hid his grief. It was his to bear, not to share. Not even with Brian. Certainly not with his crew. Nothing he did or said must affect their morale. And their lives were dependent on his skills and judgment. This stupid senseless war. This hideous loss of young lives. This sorrow inflicted on parents. On friends. The waste of it all. The wicked waste. But he must not dwell on it. He had a job to do. And he must not let himself think about those other lives that would be lost if he did his job well. About the waste that his skills and judgment would cause. He must not. And he must do his job well. For the sake of peace.

But silently he read and re-read poems by another serving RAF officer, John Pudney, who wrote in ‘The Dead’, ‘These, wishing life, must range the falling sky, Whom an heroic moment calls to die.’ And silently he agreed, ‘You shall have your revenge who flew and died, Spending your daylight hours before the day began’, and made a vow for Frank. Then later, caressed and warmed by his first English summer, he read in ‘Men Alive’: ‘Enough of death! It looms too large in words…Enjoy the sky, Possess the field of air, Cloud be your step, The west wind be your stair.’

David took comfort again in the delights of flying. On a daytime cross-country to the Welsh coast he was exhilarated to fly at 18 000 feet, the highest he had been yet. But a six-hour cross-country two nights later proved very wearying. With no visible horizon and in thick cloud part of the way, he had to fly on instruments the whole time. David, always making light of difficulties, simply wrote in his diary, We were not sorry to land. Even under good conditions night flying was a strain. And when they commenced ops, many would be flown at night under horrendous conditions.

One evening a highly concentrated bomber stream passed overhead.

‘Just think how the Dutch and French must feel seeing them!’ the crew gloated.

Then suddenly it was their turn to gladden the hearts of the French. On 18 August, only 14 days after their familiarisation flight on Halifaxes, David and his crew found themselves listed for a diversionary exercise over the Normandy battlefields, where the fight between the Nazi occupying army and the Allied invasion forces was still raging. This was one of Butch Harris’s strategies. Smaller groups of aircraft were often deployed over areas away from the main target to confuse the enemy and divert attention from the Main Force. The casualty rate in Bomber Command was always higher than in Fighter, Coastal or Transport Commands. Although aircraft production had been stepped up, even in 1944 the replacement rate for planes and crews could not keep pace with casualties. During the invasion month of June alone almost 2600 Bomber Command aircrew were lost. To make up the required numbers sprog crews in aircraft that had been retired from active service were pressed into use.

So it was that on the night of 18 August, many young men, not fully trained, set off in defective aircraft to fly as decoys over enemy territory.

‘It’s one of those sitting duck flights we’ve heard about,’ they quipped as they climbed aboard. ‘Let’s hope the old girl doesn’t conk out tonight.’

David’s notebook with details of corkscrew manoeuvre for evading enemy aircraft attack

They flew over the Channel to Caen, where they could see the mayhem of the battle below, before they headed for Bayeux and on to the Irish Sea. They were chased by an enemy fighter, but it sheered off when they took evasive action. This was fortunate, David, master of understatement, wrote in his diary, as we had no mid-upper gun turret. Thankfully, they flew home through a strong cold front, to land in rain at base.

‘All that corkscrew practice sure paid off, Skipper,’ the crew commented. ‘And the old crate made it!’

The rain continued for three days and flying was washed out. Then, although they had completed only two out of nine bombing exercises, they had sufficient hours overall, and were deemed to have completed the course.

David, with a total of 381 flying hours and nine training courses over 22 months, was assessed as a proficient heavy bomber pilot.

Next day he left for London to complete the formalities for his commission, which had come through early in August. Now as Pilot Officer Mattingley he dined in the Officers’ Mess. He was sorry to be separated from his crew, but appreciated the opportunity to mix with more experienced men. London was still under flying bomb attack, so Australians were allowed there only on official business. After dealing with his, David went to a tailor in Savile Row to be measured for his officer’s uniform. Not only did he now have to pay Mess charges for meals, he was also responsible for providing his uniform. ‘Just as well my pay’s gone up a bit,’ he thought ruefully as he enquired the cost. ‘But it’ll take more than a few weeks at nineteen shillings and tenpence a day, to cover this lot.’

A flying bomb landed nearby while he was at the tailor’s, and on leaving he was stopped by Service Police who checked his pass, then gave him a lift to RAAF Central Stores. Here he bought the rest of his necessary kit, pleased to be at last entitled to a raincoat and a tin trunk. No longer would he have to cram all his possessions into kitbags.

But David still wasn’t finished with training. A transport took him and his crew the 20 miles from Lindholme to No. 1 Lancaster Finishing School, Hemswell, and more lectures. On the second day David learned about Lancaster engines and airframes and they all spent time in an aircraft finding out the whys and wherefores of everything so that each crew member knew where every item of equipment was located.

Lancaster returning home (Photo by Paul A. Richardson)

‘She’s longer than a cricket pitch,’ Birdy marvelled, ‘and I’m on the boundary!’

Everyone forbore to remark that the rear gunner’s position, most vulnerable in the plane, was more like silly mid-on.

The Lancaster, almost 70 feet long, stood nearly 20 feet high on massive wheels nearly as tall as a man, with a wingspan of 102 feet. Powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, it had a cruising speed of 216 miles per hour, bomb load capacity of 14 000 pounds, fuel for up to 2000 miles and could climb to 22 000 feet. It was ideally suited for penetration over Europe. ‘What a wizard kite!’ they all agreed, appreciating that its black belly made it harder to see from below, and its upper surfaces, painted in camouflage colours and patterns, disguised it from above.

Air-sea rescue and parachute and dinghy drill again featured large. A dummy fuselage fitted with devices registering each crew member’s actions made dinghy drill very realistic. As pilot, David would be the last to leave the aircraft and his exit was not easy. The main escape was a hatch on which the bomb aimer lay, forward of the pilot’s position in the nose. This would be used by bomb aimer, flight engineer, navigator, w/op and mid-upper gunner, who would all bale out before the pilot. The rear gunner would also leave through the main escape hatch if time permitted, or if necessary direct from his turret.

After a week at Hemswell, and fifteen months since David’s first thrilling sight of a Lancaster in New Zealand, they had their first flight. He was ecstatic. The Lanc is a really beautiful kite, by far the best I have flown. She is remarkably manoeuvrable for her size and is light on the controls. On this flight they saw a Halifax on fire make a forced landing. Then after a couple of circuits David went solo in a blinding thunderstorm, which tested everyone’s nerves.

Lincoln Cathedral, welcome landmark for aircrews returning from ops

David was also ecstatic about a visit to Lincoln. This is obviously a cathedral city and one can feel the atmosphere. They climbed the steep hill, and he wrote afterwards, The famous cathedral almost beggars description. Nevertheless, he filled more than a page of his diary, extolling its beautifully proportioned towers, west front, wonderful stained glass, superb wrought iron choir screens and the carved angels adorning the choir. But he did not yet know how comforting the sight of the great towers on the horizon were to become to the crew returning from ops.

The following day, 3 September, marked five years since war had been declared. ‘How much longer will it go on?’ everyone was wondering. ‘How many more aircrew will be lost before the carnage ends?’ It was also the first anniversary of David’s arrival in Britain and he was pleased that Reg Murr had returned from London where he had received his overdue commission. Australian aircrew were often frustrated that despite their intensive training and qualifications, they seemed to be passed over in favour of English crew. Rain interfered with flying, as did an unserviceable aircraft, forcing them to continue until 0300 hours to complete the required number of circuits and bumps. And they had had only one fighter affiliation practice.

At the end of the week, after only three days in Lancs, it was time to pack up again. David’s tenth course was over. He and his crew had passed and were ready to join their Lancaster squadron.