Three days of snow and gales. Ops and training scrubbed. Getting out of bed, slipping on the ice on the hut floor. No wonder the Romans did not enjoy building Ermine Street, David wrote in his diary. ‘Any more than I enjoy going to Happy Valley,’ he thought. Aircraft run-up, briefing done, sitting in the aircraft, engines running, about to take off, red Very light. Infuriated crew. Briefing and scrubbing becoming monotonous. Foul foul weather. Too foul even for Bomber Command. Obviously the European winter leaves much to be desired, he wrote. Oh for the sun and warm sands of home. Two more days of snow and every wind that blows. All hands to shovels to try to keep the runways clear.

Then on 16 November they were up and away again at last and in daylight on Battle Order 196. It was another tactical raid, with the grim purpose of obliterating the town of Düren, a major supply base for the German army, and cutting communications behind German lines

Smoke clouds from bombing raid on Düren, 16 November 1944.Smoke often rose to 10 000 feet or more.

at Julich and Heinburg. A special message from Bomber Command was read at briefing, informing them that the trip was in support of the biggest operation since D-day - the American Army advance on the Rhine. ‘So we need a good prang, boys,’ the Wingco said.

Flying in G George, they were joined for the first time by their new navigator, Flight Lieutenant Charles Gardiner DFC, who was on his second tour of operations. The crew were a little apprehensive at having a screened bod of such experience. Drew was especially nervous as Gardiner was also ‘the Y King’, the station’s radar instructor, and he felt sticky in case his own technique was not approved. But David was pleased. G George was to be one of the three lead planes in a gaggle, which required accurate navigation and flying. Charles was an efficient navigator and fitted in well.

They had their first scare of the op before they even took off. While still in dispersal a gunner from another aircraft accidentally fired some rounds which passed over their heads. ‘A close shave,’ they all agreed.

The Lancasters seemed to fill the sky like a flock of giant black crows as the stream flew over England. Over France it divided into three groups, each heading for its specific target with Pathfinder Master Bombers leading the way. They had another scare when one aircraft did not follow the instruction to bomb at 10 000 feet and dropped its load from above them. ‘What bastards!’ they yelled, as David had to jink, manoeuvring violently to avoid the bombs.

Turning away from the burning and blackened ruin of what had been known as the Queen City of the Rhine, with the sickening smell of cordite and the sound of exploding flak so loud it could be heard above the engines, David joined the stream heading for England.

Flying in the fading light over Lincolnshire, featureless under snowdrifts, he was grateful, as always, to see the splendid shape of Lincoln Cathedral on the skyline. They were nearly home. Wonderful how the faith and vision of men so many centuries ago, and their magnificent handiwork, still proclaimed hope and salvation. Now, other men, in circumstances so different, also needed the message.

Breathing easily again in air unpolluted by funeral pyres, they made their way to interrogation. One of 625’s aircraft was missing.

‘That was no scarecrow we saw. Could have been our mates’ kite going down in flames,’ Drew said sombrely.

The lost crew had only been on the squadron for four weeks.

The reconnaissance photos showed a concentration of bomb craters without parallel in any previous attack by the RAF. Virtually one hundred per cent accuracy had been achieved. It was the good prang Butch Harris had hoped for.

Two days later it was back to the oil refineries at Wanne-Eickel. This time David flew with a sprog crew. All his crew went out to George in the morning for the run-up, and to show the new crew their daily inspection routine and their particular jobs. Then, after briefing and their flying meal, they took off at 1540, with second dickey pilot, wireless operator, bomb aimer, flight engineer and rear gunner. Of the regular crew, David had only his own navigator, Charles, and Birdy who took the place of mid upper gunner.

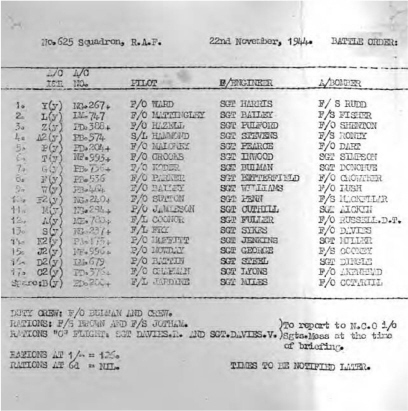

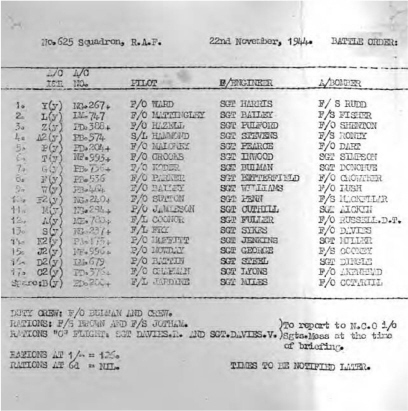

A typical Battle Order of 625 Squadron, No 200, for 22 November 1944

Pop, Cyril, Boz and Drew went out to see them safely aboard, then cycled to the take-off end of the runway.

Drew said, ‘I felt like a lost soul. For the first time it was brought abruptly home to me just how attached to one another we have become.’

They hated to think of their skipper, their Dave, going off without his team, the crew he knew he could rely on. He had a tough enough job as it was, without worrying

about men who might not cope when things got hot. They joined the Wingco, padre, airfield controller and other officers, together with another crew whose pilot had a second dickey too.

‘I damn near howled before George even came along,’ Drew said.

They gave G George the thumbs-up sign as it came abreast with their Dave at the controls. ‘Godspeed and a safe return.’

David returned the thumbs up and Birdy went one better, swinging his gun turret onto his mates and pretending to fire a burst at them.

The engines roared into life, the tailplane, fins and rudders shuddered with the blast. Moving slowly at first, George gradually gathered speed down the runway and still more speed until it took off. Drew watched until it disappeared into the mist, afraid to look at the others in case they saw the tears in his eyes. Empty and lost, they returned to the Mess, their ears reverberating with the roar of the kites circling to gain height. Five hours to wait until the first ones would return.

Aloft in George, David was not happy either, wishing he had his own crew at their posts, fearful that these sprogs might inadvertently do the wrong thing under pressure and make a fatal mistake. He told the flight engineer to do exactly as he was ordered and nothing else. He ensured that the bomb aimer did not have the doors open too early, that the w/op checked that the photoflash had gone, and that all crew members were properly on the job.

It was a clear night. The target indicators were easily visible, so the attack was concentrated. Particularly active searchlights coned several kites. But with good cooperation from Birdy, David evaded them all and wrote afterwards, This part of the attack should have proved most instructive to the new crew.

On the return flight, the w/op picked up a message near the English coast, diverting them to Knettishall, where George landed first in blinding rain. It was a US base for Flying Fortresses and the Intelligence Officer who questioned them was amazed at the bomb load they carried, compared with that of the Fortress.

They enjoyed American hospitality, delighted at the excellent meals in such stark contrast to what British services and civilians were used to. ‘Grapefruit juice, peaches and cream, and bacon and eggs! And this is just an ordinary breakfast, not a flying meal!’

At Kelstern, the others had waited up to see them home until advised of the diversion. On seeing them safely back after more than 24 hours, they disguised their relief with banter. ‘You bludgers! Living off American fat while we didn’t even leave the station, not even for a night out in Grimsby!’ Grimsby, as they all knew, was singularly devoid of attractions.

Dense fog rolling in from the North Sea brought everything to a standstill on the station. Visibility was nil. But there were two unwelcome personnel movements. Everyone was disappointed to hear of the Wingco’s posting to another station. For two months he had been a good leader and they would miss him.

The crew were sad, too, to learn that Murga had now been moved to Rauceby Hospital, and was likely to be repatriated. Another fracture, another loss.

For his part, David was keeping a close tally of his own movements. He had now completed two-thirds of his tour. His next op would be his twenty-first.

BACK TO GERMANY

David and his crew were on the Battle Order again three days later. Going into the Mess for the pre-flight meal with his friend Jack Ball, they had, as usual, to be checked off a list of crews, ensuring they were entitled to the coveted bacon and eggs.

‘Mattingley’s,’ he said, and the WAAF ticked off his name.

‘Ball’s,’ Jack said.

The WAAF looked up from her clipboard. ‘Balls to you too,’ she retorted.

The queue broke into laughter.

Jack explained, ‘Ball’s my name’.

She blushed furiously. ‘Sorry, sir.’

‘No hard feelings,’ he assured her.

Jack, David and his other English friends Clem and Sandy chuckled as they polished off their bacon and eggs. It made a good start to the op and a good story to share with the rest of the crew.

David was very glad to be flying with his own crew again, especially as it was to be their longest trip yet, to southern Germany, almost seven hours in the air. This time they were in L Love again, with a cookie and sixteen 500s. Because they were penetrating so far, it gave the enemy more time to organise defences. At briefing they were told to expect heavy opposition from fighters, so the normal strategy was to be followed. They were to change route several times to confuse the enemy and to try to lure the fighters away from the intended target. This was the railway marshalling yards at Aschaffenburg, another major supply depot, and the attack was in support of the advancing French army.

The outward flight was uneventful. Drew recorded that the only happening of note was Dave having a leak out the port window while Cyril held the plane steady.

David always flew hands on. He never used the automatic pilot, as it required precious seconds to disengage, which could be crucial in an emergency. So he could not use the Elsan like the rest of the crew. Some pilots carried a bottle or tin, but he did not. Nor did he use the flare chute, as others did, because this would also mean leaving his position at the controls.

When the bombers ran into ten/tenths cloud as they approached the target, an elaborate tactic with Pathfinder markings and Master Bomber had to be abandoned. But to everyone’s consternation sky-markers which had been dropped instead were bursting above the planes. Drew and Charles worked well together and Drew gave the Y king full credit for perfect timing as he let the bombs go over the red glow already visible below.

On the return, Pop picked up enemy aircraft on the Fishpond warning radar screen, and soon afterwards fighter flares began falling. It was a stomach-churning moment when one fell within a hundred yards and David wrote, We felt singularly naked expecting attack. Drew admitted he felt scared sick and everyone kept an extra good search going. Seven other Lancs were illuminated and they saw a number of attacks over the next half hour. All 625 Squadron’s Lancs returned, but two from the force were lost.

Over the next five days the weather was impossible for flying. Snow was falling almost daily, culminating in a mini blizzard which created drifts several feet deep in places. It was frustrating. The leave to which they had been looking forward was postponed by a week because they were needed on the squadron, and yet they were unable to fly.

As usual, when not in the flight office or out at dispersal, David put the time to good use in the intelligence library.

Sawing up wood for the Mess fire helped keep them warm. The coloured lights of half-a-dozen Very cartridges tossed into the fire made for a brighter and more lively evening. Especially as the Groupie was standing with his back to the fireplace!

There were not many options for entertainment, but as always they enjoyed simple pleasures. Making toast on the hut stove and eating anything we could scrounge was a good deal of fun.

On the Saturday they took some of the ground crew to dinner at the King’s Head in Louth. As they always serviced our aircraft so well and were most willing and helpful, it was the least we could do for them.

Then, at last, they were given their own aircraft again, D Dog. David was delighted. It is much easier having one of our own, as we can take good care of it and have everything to suit us. On their first flight in D Dog they again took a second dickey crew, mainly Canadians. The sprog w/op and gunner were sick, so David was thankful to be able to take Pop and Boz, though Drew was again left lamenting, as was Birdy this time and Cyril too. At the morning run-up they took the new crew through the routine checks and all they needed to do, and at the briefing David showed them the procedure for emptying their pockets into named paper bags.

But they could carry a talisman. And many did. Teddy bears and other soft toys were popular. Or it might be a so-called lucky rabbit’s paw, a trusty pocket knife, or perhaps a cigarette lighter with sentimental attachment. Perhaps a cherished lock of hair from a wife or child. Or a St Christopher medallion. Sandy always took his officer’s cap. On one op it was ripped by shrapnel. Much to his annoyance, while he was home on leave an uncle who was a tailor mended it very skilfully. David carried the small black Bible he had bought at St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne during his training at Somers. It fitted snugly in the left-hand pocket of his battledress, just over his heart, and it had been on every flight with him since his first at Western Junction.

After obtaining escape aids, maps and currency, David ensured that the sprogs noted all the necessary gen from the blackboard, including the method and time of target marking and the wave in which their aircraft would fly. After the talks on tactics and weather, they collected flying kit and rations from the crew room before boarding the transport out to dispersal. David was concerned that the engineer seemed uncertain about parts of his duties, so he took him through many details himself. Nor was the new crew disciplined or trained well. David found their habit of leaving their mikes switched on very annoying, as the static interfered with his concentration.

It was another long flight into southern Germany, almost seven hours overall. This time the target was Freiburg, a minor railway centre, held by German troops who would impede the advance of American and French troops from the west. In bright moonlight they were horribly exposed, so with an inexperienced crew David was extra thankful that opposition was not too heavy.

On the homeward route skirting neutral Switzerland, the sight of the twinkling lights of Basle was amazing after blacked-out cities, and the snowy grandeur of the moonlit Alps was awe-inspiring.

Descending through cloud they again experienced the uncanny effects of St Elmo’s fire playing along the wings, props and guns, turning the perspex windscreen bright blue and sending flames leaping from its framework to David’s hands. He was glad to break through the cloud at sea - a much safer alternative to coming out over land - and came in low towards Louth with its familiar radio beacon call sign.

As the weather was rapidly closing in, he was thankful to see the Kelstern searchlights making their distinctive V pattern to guide them. David ensured that the men put their names on the returned list, and took each one through his specialist interrogation, reporting any snags, then went through the general intelligence interrogation with them all. By 4 am he was more than ready for bed, glad to be finished with his duties and relieved of his responsibility for the sprog crew.

David woke at midday and went out to D Dog to check it was ready for the next trip. But during the afternoon another crew used it for a training flight and on take-off had flown into a flock of plovers, damaging perspex and two radiators. Quick to make the best of a bad situation, David collected some of the birds and while the erks worked into the night to get D Dog in flying order again, he and the MO enjoyed cooked plover for dinner.

Next morning. he was glad to have had the meal, when they were served an ordinary breakfast instead of a flying meal before being sent off on a rushed op.

It was 29 November. Dortmund was their destination, in the deadly, heavily defended Happy Valley.

And they were flying on Battle Order 204.