18 ‘It is so good to be

alive!’

It was a great day for David when, a week before Christmas, he was allowed out of bed and took his first steps with the aid of a crutch on his left side. All this left-hand business took some getting used to. First the basics of eating, drinking and washing. Then shaving. What a challenge! He felt tempted to grow a beard. Writing too. Now learning to use a crutch was another. But he was determined to master it as quickly as possible so that he could escape from his cell and fraternise with the chaps in the main ward. It was good to swap stories, reminisce and exchange information about home.

They came from all over - London, Leeds, Birmingham and Derby, Wales and Scotland, as well as some local Lincolnshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire lads. There were a couple of Canadians, a Pole and even a chap from Turkey. And he was pleased to discover four other Australians,

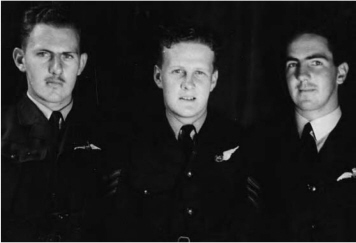

David by Spitfire, Loughborough Medical Rehabilitation Unit.Airmen from overseas who had no civvies were issued with trousers and white jumper.

one from Tasmania, two from South Australia, and a West Australian, ‘Ted’ Bear from his own squadron, who had also been wounded on the Dortmund raid. ‘We’re quite a little League of Nations here,’ they told him, pleased to greet their released cell mate. Suddenly the boundaries of his world expanded again.

David was sobered to see how severely some had been wounded - aircrew members who had lost an arm or a leg or an eye, and in the padded cell next to him an erk who had fallen on a circular saw with shocking consequences. But most of them were stoically making the best of their situation. He was thankful that burns patients were in a separate ward. Some of those poor fellows were hideously scarred. It was anguish to see them and think of what they had been through and would always have to endure.

When Alan Scott came to visit, caring as always, he took David on his first outing. ‘Have to get you out of this place for a while, old chap, before they certify you!’ They went to Sleaford, the nearest town, where Alan was keen to acquire the purple and white diagonally striped ribbon which would denote David’s award. David was too embarrassed to ask for it, but Alan certainly was not. Walking into the haberdashery, he enquired, ‘Do you have the ribbon for the DFC? It’s not for me. It’s for my friend here.’ Afterwards he wrote to David’s parents, He turned all sorts of colours! He is most modest about it. Because he wouldn’t, I had to ask one of the nurses to sew it on his uniform. It was his walking-out uniform. They had had to cut his battledress off him when he was brought in. But David refused to wear the two narrow gold stripes which denoted wounds received in two attacks.

Another coloured Christmas card available for servicemen to buy to send home

A large bough cut from a pine tree in the garden was brought to the ward for the men to decorate before Christmas. ‘We’ve got all the snow and tinsel we need,’ they said, raiding the store for cotton wool and cadging bales of Window from mates on nearby stations. It was completely different from all the Christmases David had ever known, but he wrote to his parents, I was surprised how cheerful a hospital could be at a time like this. On Christmas Eve he joined the group of staff and up patients going round the wards singing carols, and afterwards laboriously made his way out to the little chapel in the hospital grounds to attend a midnight communion service.

It was the coldest Christmas for over fifty years and the white one they had hoped for. On Christmas morning he limped again to the chapel for the service of lessons and carols, delighting in the fur of snow like ermine over the shrubs along the path and the tinsel of icicles glittering on the trees after a hard frost, while floating fog billowing around the old buildings softened their stark institutional outlines. Everyone enjoyed the luxury of a traditional Christmas dinner with all the trimmings and received presents from the Red Cross. And in the evening David shared a splendid cake from his mother.

But as ward lights were dimmed and men settled down for the night, the same thoughts were in each mind. Would he see another Christmas? Would the war be over by next Christmas? When would they be able to go home to their families? And everyone thought of families they knew where there would never again be a son or brother or father or uncle in the circle around the Christmas table.

Brian, now at Binbrook, the RAAF 460 Squadron station near Kelstern, visited on Boxing Day and together the brothers went to fog-shrouded Lincoln. They struggled along the slippery cobbled streets, glimpsing medieval buildings ghostly in the drifting mist, and slowly toiled up Steep Hill. Then suddenly as they reached the top they emerged from the fog to see the cathedral in all its ancient splendour bathed in sunshine. David caught his breath. It

David’s medals; L-R: Distinguished Flying Cross, 1939-45 Star, France and Germany Star, Defence Medal, British War Medal, Australian War Medal

seemed an epiphany, an allegory of the triumph of light over darkness. Entering through the great west door they paused to take in the sweep of the lofty arches with the light streaming through the windows above and his soul sang with the glory of the great church, hallowed by worship for almost a thousand years. As they sat quietly in the nave the sound of the mighty organ rolled forth, reverberating through them like a score of musical Merlin engines. Then from the exquisitely carved Angel Choir voices soared in the powerful anthems of Handel’s Messiah. David felt washed, bathed, soaked, steeped in its healing affirmation. He truly knew that his Redeemer lived and whatever might happen, held him in His almighty love.

Early in January David was thrilled to be given three weeks leave, the most he had ever had. Thankful to escape for a while from the sounds of pain and haunted dreams, he was determined to enjoy it. His head bandages and skullcap had been removed several weeks earlier, and he had had a second round of X-rays, much less painful than the first, which had revealed satisfactory healing. The hospital barber had cut his hair, a difficult job as it was still matted with blood, and it had now had time to grow a little and begin to cover the wound. He had discarded his crutch but still had to wear a sling on his right arm, and when he returned he would have to undergo a second operation on his right hand. But for now the horizons of his world had increased.

His first port of call was Kelstern where he was deeply touched by the warmth of the welcome he was given. Everyone was so glad to see him and he was delighted to see Birdy and Charles again and his ground crew, but not surprised to find that D Dog was still out of service. ‘The poor old Dog took a hiding and she’s still licking her wounds,’ an erk told him.

Then he went to Brighton to see Reg Murr, who was awaiting repatriation. ‘No more waiting for letters from Mary,’ he smiled at his old navigator. ‘Won’t she be pleased to have you home!’ Reg brightened. ‘Think of us shivering our socks off here when you’re basking in the warmth of sunny Queensland stuffing yourself with bananas,’ David said, half enviously.

Murga smiled. ‘I will,’ promised the man of few words. Then, suddenly serious, he said, ‘Thanks, Dave. It was an honour to be in your crew.’

David looked at the thin figure with the greying face which betrayed the stress and sickness Murga had suffered. ‘I’m glad you were part of it. You are a gen navigator. We certainly had some moments, didn’t we? But we’ve done our bit for peace and freedom.’

Murga nodded.

They shook hands, looking long into each other’s faces. Then David squared his shoulders and turned away. No looking back, he told himself. He could not bear to see Murga’s face crumpling. And he knew he could not hide his own feelings. These partings…At least this time he had been given the chance to say goodbye.

From Brighton, he made his way to Kent, where Cyril was home on sick leave. It was good to meet his parents and sisters and to be so warmly made part of a family again. Next stop was Birmingham where, in driving snow, he met up with Pop and Drew to attend Boz’s wedding. Looking at Boz’s face, so young and happy, and Ann’s bright with love, David felt a lump rising in his throat for the pair in their uniforms. ‘Let neither Hun nor gun put these two asunder,’ he prayed. He felt a pang, too, at parting again from Pop and Drew, but at least he was on his way to another reunion. David McNeill was being invalided home from the Middle East and Dights had been invited to stay with the usual warm welcome.

Arriving before his friend, Dights watched the family reunion, wondering when it would be his turn, moved by the emotion of it all, as the sturdy little Scots mother embraced her oldest laddie and wept, while his father struggled to restrain his tears. When Dights was introduced to Scottish dancing he exclaimed, ‘It certainly warms you up. Now I know why Scotsmen wear kilts.’

The highlight of the week was a Burns Supper. He was fascinated to see the fierce pride with which his Scots hosts and friends celebrated their ain poet. Robbie Burns knew about farewells and death, the pain of parting and loss. ‘When day is gone, and night is come And a’ folk bound to sleep, I think on him that’s far awa’ The lee-lang night, and weep.’ He knew the value of friendship. ‘It’s coming yet, for a’ that, That man to man the world o’er Shall brothers be for a’ that.’ Dights found himself listening with new ears, identifying with the meaning of the poems in a deeper way than ever before. When it was time for ‘Auld Lang Syne’, he was moved by its poignancy, ‘Should auld acquaintance be forgot And never brought to min’? Should auld acquaintance be forgot, And days of auld lang syne?’

‘I’ll never forget you, David lad,’ he said as they climbed the stairs to bed. ‘You’re the best friend I’ve made since I came to Britain. And your family has certainly given me ‘a cup of kindness’, full and overflowing.’

Back at Rauceby, a bumper mail awaited him - letters, airgraphs and parcels. So he set to at once to answer at least some, before the second operation on his hand. The surgeon, who was a King’s Honorary Surgeon, was still in doubt what it would achieve. Fortunately it went well. The last piece of metal was removed and the tendons rejoined. And after a few days he was allowed up and about. But it was still uncertain whether he might require further surgery.

He was writing left-handed again, as his right hand was in a splint once more. After receiving 23 more letters and five parcels in one batch, he wrote to his parents, asking them to thank the donors. Parcels are always acceptable in hospital, and I have been distributing largesse like a philanthropist or public benefactor. Alan Scott also wrote to David’s parents. He had received a letter after the second operation, but as usual David gave no personal information whatever, so Alan planned to visit and check up.

The hospital atmosphere in the grim old buildings with their barred windows was depressing. And David wondered yet again if and when he would get back to active service. He himself unwittingly caused a delay in his discharge. Italian POWs awaiting repatriation were working on local farms and one day just after the splint had been removed, a group saluted him. Without thinking he returned it, ripping stitches out of his right hand. So, more had to be inserted.

Men were moving in and out of the hospital every week. New casualties from missions were being brought in. Others were moving out, which was encouraging or unsettling, depending on whether they left by the front door on their own feet or were carried out through the back in a box. Even with those who walked out, David knew it was unlikely that their paths would cross again.

Then suddenly at the end of February, the future seemed brighter. It was decided that he would not need a third operation. After three months in hospital he was to be transferred to a convalescent and rehabilitation unit at Loughborough in Leicestershire. Run more as a club than as an Air Force station, uniform was not worn, rank was ignored and patients, who ranged from an Air Vice Marshal to Pilot Officers, mingled freely, with a fine sense of camaraderie, understanding and respect for what others had gone through. There were amputees who had lost a foot, or a leg, some below, some above the knee, others still right up to the thigh. Some had lost a hand or an arm. David counted himself lucky indeed and was inspired by their fortitude, encouraged by their positive attitudes, philosophy and humour.

The program began at 9 am and finished at 4 pm, and the men worked hard with exercises, basketball, badminton, archery and swimming. David’s first treatment for his hand was rather painful, as it was bathed in almost boiling hot wax, followed by massage and exercises to strengthen the tendons and regain mobility in his fingers. Treatment was holistic, much attention also being given to social interaction, relaxation, and mental stimulation. David particularly appreciated hearing eminent historian G.M. Trevelyan twice, and also the head of Pathfinders, Australian Air Vice Marshal Bennett, and Earl Templeton, known as ‘the father of the House of Commons’.

Every week the men were taken for a ramble in the countryside, where the loveliness of spring unfolding was a delight and played an important part in David’s healing, bringing new hope. As the milder weather thawed his winter-chilled body, spring’s promise warmed his grief-numbed heart. He revelled in each new sign - fruit trees bursting into blossom, hedgerows and hawthorns beginning to tinge with green, the first daffodils, the joyous song of birds. And in mid-March he was able to write, It is so good to be alive and about these days! Particularly as a more optimistic view can now be taken of the European war. In December the Allies had taken Ravenna in Italy; in January the Russians had captured Warsaw and Krakow and reached the Oder; while in February British troops reached the Rhine on a ten-mile front and by mid-March the Allies controlled its west bank.

He reported proudly to his parents, I have now cut down the number of letters I owe from over 100 to 27. For three months people from all over Australia and Britain had been writing to congratulate him on his DFC and wish him a speedy recovery. And in his meticulous way he was determined to answer every letter. He particularly appreciated one from Drew’s wife, Thel, who wrote, Thank you again for what you did. The thought of what might have happened still gives me the creeps. I know the boys are proud of you.

His first headmaster wrote, If your ears have been burning, it will be because you have been the subject of much talk among the young things here.

His Uncle Arthur wrote, Good for you doing your best to defend democracy and thereby helping to make the bad old world better and happier. An example of duty to country and conscience. You are young and have had the great advantage of visiting other countries, the experiences which will or should be of inestimable value to you in after life. Would that I had had them when young, my mental horizon would have been much expanded.

Back home, his parents had also been receiving telegrams and letters from every Australian state as people read in the papers of David’s feat, his devotion to duty, his award, and wrote offering congratulations and best wishes for his recovery. They ranged from an aunt who remembered nursing David as a fat and lovely baby, to those, including teachers, who had watched him grow up. All shared memories and sentiments to comfort and uphold his parents. A former neighbour wrote, My mind goes back to the first time I saw him in the garden at ‘Fairlawn’, with his red jumper, a very bonny boy. How little we realised just what the future had in store for him so young. But he has proved what sort of a man he is.

His last headmaster gave wise encouragement. He is having great experience now, and will return with a knowledge and breadth of vision that will make him a man a generation ahead in development compared with when he went away.

Peter Lord’s mother wrote, Do you know David sent me a cable from hospital. Wasn’t it marvellous of him? I do hope you will be having him home soon. Peter wrote to me about a friend of his that did not return - ‘If your number is up there is no more to it.’ We are unlucky. When David comes home I would very much like to see him.

Perhaps the most touching of all was from Frank’s mother, who wrote to David’s, No one knows but a mother, what the anxiety about our boys is to us. Frank’s brother hoped in his last letter that Frank would be home for Christmas. He only knows that he is missing. I want him to keep hoping with me that our Frank is returning. I can’t think any other way.

David also received a number of letters from parents of airmen who had been killed or gone missing, desperate for more information about their son’s fate than official communications provided. These were the most difficult letters to answer and he spent much time in correspondence with Air Force headquarters, and networking among friends and acquaintances trying to glean any available details. Usually there were none, or none that would bring any comfort to bereaved and grieving parents. But he did his best and was moved by the pathetically grateful replies he received.

The mother of Allen Morgan, one of the boys with whom he had spent time in New York, wrote, Many thanks for your letter. Yes, it was a terrible shock losing Allen. We never gave up hope until quite recently. Although I realise now he is gone, in my heart he still lives. David had sent her a snapshot taken in New York, for which she was grateful. Not a very good one of him, as you said, but the most recent. For that reason he was

L-R: Fred Clarke, Allen Morgan, David in New York. They travelled together to Britain, but after spending their first weeks at Brighton, were posted to different units and did not meet again. As a gunner, Allen was sent on ops much earlier than pilots, who needed more training.He was killed, aged 20, over Berlin on 29 January 1944.He is buried in the Berlin 1939-1945 War Cemetery.

glad he had continued the expensive practice of having studio portraits taken to send home. They could be all that was left for his parents. Mrs Morgan went on to ask for help in tracking down two of her son’s crew who had been taken prisoner, in hopes that they might be able to tell her something. So did Ron Leonard’s mother. David and Ron had trained together at Point Cook and Ron had helped celebrate David’s 21st birthday in Wellington. Now he was in enemy hands.

No wonder a friend of his mother had written, Many hearts must feel like breaking these days. Everyone was looking forward to the time ‘when the boys come home’. Not least the boys themselves.