On 21 April David wrote in his diary, Today is the great day - at last I am free from hospitals and similar institutions. Five months have been quite sufficient, and the doctors have done a good job, although my right hand is still much weaker than my left. His hand had been declared fit for flying a heavy bomber again. But in another irony of war, he was told that because of the damage to the tendons he would not be able to play the piano.

Never again would he feel the cool smooth ivories rippling beneath his fingers. Never again would he hear melodies produced by his hands. Never again would the organ respond to his touch. He thought of the piano waiting in the sitting room at home, the small organ in the corner of the dining room, the organ in the little church at Bridport where he sometimes played hymns for the Christmas and Easter services. He remembered the walks, the bike rides, winter and summer, to music lessons. His

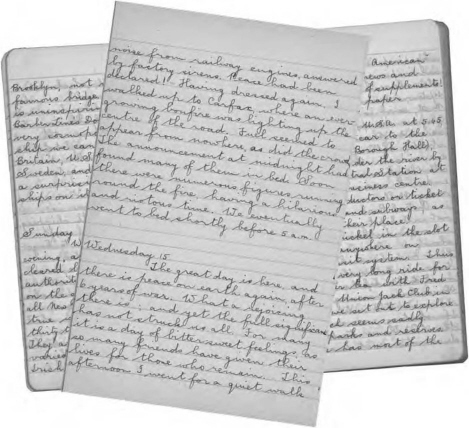

Page from David’s pocket diary, later copied into his regular diary

painstaking teacher who on frosty nights always put an eiderdown over the grand piano, which was his pride and joy. David was one of the few pupils allowed to play it. The hours and hours of practice, concerts, exams, theory with which he wrestled. The pile of music books. The thrill of mastering a new piece. Etudes, mazurkas, waltzes, sonatinas flooded back through his mind as he stood swaying in the train to London, going on nine days’ leave.

His first stop of course was the Boomerang Club, where his confidence was rather shaken when fellows with whom he had trained commented on how his hospital stay had aged him.

Cambridge was David’s next destination for three therapeutic days with Dr and Mrs Noble. Physically relaxed and mentally rejuvenated, he then went to Nottingham for his next commitment - as best man to Des Hadden at his wedding to a local girl. Sheila was one of the prettiest brides I have seen, and Des was extra happy, he wrote.

Festivities over, he caught a train to Lincoln to meet Drew, Pop and Boz and spend a cheerful evening reminiscing.

‘So when are you going to get married?’ Drew asked Pop and David. ‘Who’s going to be first?’

They looked sheepish. Pop shrugged his shoulders. David replied, ‘No plans.’

‘It would have been more interesting if you’d said “No comment”,’ Drew teased.

‘You don’t know what you’re missing,’ Boz told them. ‘You ought to start looking and get yourselves an English bride too before we go home,’ he urged.

Flying Officer David Mattingley in 1945

Wedding of Des Hadden and Sheila Houghton, David as best man, Brian (R in cap) in guard of honour

Drew would not give up. ‘Surely there were a couple of pretty bridesmaids at the wedding?’ he persisted.

‘No comment,’ David grinned.

Going home. It was on everyone’s mind and something that everyone talked about now. Surely the war in Europe could not last much longer. But it was far from over on the Japanese front. They could be sent to India. Or Burma. Or the Pacific. They all knew that for Australians there was still more action. But at least they would be closer to home.

With the decreasing need for air offensive, wartime airfields which had sprung up all over Lincolnshire and Yorkshire were being closed. David found many changes at Kelstern.

It took two days to track down, collect and repack all his kit for the move to his next posting with the squadron. He wrote, I do not like breaking the ties with Kelstern. But the last op from Kelstern had been flown on 4 April, and next day, 4 May, he also was off to rejoin the squadron now based at Scampton. There the Personnel Officer wanted to send him back to a Heavy Conversion Unit.

David, however, had other views. He phoned the Wingco, he was most pleased to have me back, and the Wingco arranged that he should take over the crew of the B Flight Commander, who had finished his tour - an all-British crew except for one lively Irishman. It is remarkable how few folk I know on 625 now - there are only two crews who were on the squadron when I left. The others have ‘had it’ or have been screened. Today the Wingco left. He was very good to me and I am sorry to see him go, he wrote.

On 25 April 625 Squadron had flown its last mission. The target had been Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s retreat in the Bavarian Alps. It proved to be the last daylight bombing operation of the war.

With 23 missions to his credit, David’s days and nights as a bomber pilot were over.

Now with growing excitement he and everyone on the station anticipated the collapse or capitulation of Germany, and listened eagerly to every fresh news bulletin.

On 7 May he wrote, I was in the Mess most of the day listening to the news bulletins. Each one has been better than the previous one and the climax came with the great news of unconditional surrender. Immediately he went over to Hemswell to be with Drew, Pop and Boz, with whom we did our little bit towards victory. They were sorry that Murga had gone back to Australia and that Cyril and Birdy were on screening leave. But, he wrote, it was great for the four of us to be together.

Tuesday 8 May, the official VE Day, dawned fine at Scampton, where all personnel attended a thanksgiving church parade in No. 1 Hangar. David wrote to his parents, It is as if a cloud has been lifted from the face of Britain.

In his diary he wrote more soberly: It is wonderful to think that the victory for which we have striven for over five and a half years is at last here. What losses there have been in this struggle which has come to such a happy conclusion! Bomber Command in the course of dropping almost 1 000 000 tons of bombs has lost nearly 10 000 aircraft by enemy action alone. Others were brought down by ice, some crashed in England, and others were too badly damaged to be of further use.

Over 50 000 men were killed, while others were POW or wounded, out of 110 000 men who passed through the Command. This is the price that one branch of one service has paid.

In fact nearly 26 000 of those who died flew from Lincolnshire, and the anniversary of Frank’s death, on a mission from Scampton, was only days away. David spent the afternoon quietly; reflecting, remembering. Frank, Peter, Tas, Allen, Ollie, Arthur, Jimmy, the Brock brothers Jim and Joe…and so many others he had known.

He listened to Churchill’s historic speech and went with friends into Lincoln, where they found a gala atmosphere, streets and buildings bedecked with flags of many nations. At 9 pm they gathered in the celebrated White Hart Hotel to hear the King’s speech. After darkness fell, the cathedral was illuminated by searchlights, a magnificent sight which David would never forget. From its towers rang out peal upon peal of victory joybells. People thronged the narrow streets and began dancing. Joy and thankfulness embraced everyone as strangers hugged and laughed and sang in the elation of victory. Back at Scampton, although all pyrotechnics had been locked up, David and a mate had managed to secure a substantial supply, and he wrote We made good use of them and eventually got to bed as dawn was breaking.

David, being now in the position on the squadron that I can do almost anything I wish, decided to go flying with a scratch crew. There seem to be a number of chaps, including some erks, who want to fly with me, so we shall take them whenever possible. All 625 staff seem pleased to see me back again, but I am the one who is most glad. It was exhilarating to be in the air again. David hoped to go on mercy missions, dropping food to the starving Dutch, bringing back POWs, and also taking ground crew on ‘Cooks Tours’ to view some of the op sites.

But on 25 May all Australians were grounded and withdrawn from crews.

David had made his last flight as a Lancaster pilot.

The consolation was that they would get some leave. He headed for London where victory celebrations continued. A gala atmosphere still reigned, with flags and bunting brightening the drab, war-weary streets whose buildings had not had a coat of paint throughout the war. It was thronged with service men and women, and after the years of stress and tension an air of relief prevailed.

Eager to catch up with friends and acquaintances and to find out all he could about others, he spent two days at the Boomerang Club. Most POWs he met were fitter than he expected. But he wrote, Some have had very gruelling experiences in German hands. Many had to do forced marches in the depths of winter, with very little food. Those who were liberated by the Russians did not enjoy the treatment by them. He was glad to meet Ron Leonard, who with his whole crew had been POWs. Another POW was the only survivor when the ‘Oh! My profile!’ pilot’s plane was shot down.

He spent time at Kodak House, too, on the grim business of making enquiries about casualties, and he wrote, The toll of war is not light and there are many faces that one misses in the Air Force, which has had such heavy casualties. Looking back on the happy times we all had at Church Broughton I thought of those we shall never see again. Out of 19 crews only 3 survived their ops intact. He listed them in his diary. Seventy two men out of 133 became casualties. Three men were wounded, 23 became prisoners of war, and 46 were killed.

But they were not just numbers. Not just statistics. They were men. Each had a name. And every one of them had a family. And friends. So the pain and suffering spread far beyond each man who had gone through the horrors of hell and the valley of the shadow of a hideous death. Into distant homes where they would live on as a photo on a mantelpiece, a snapshot in an album, a bundle of letters in a drawer, a story of courage and gallantry remembered and recounted at Christmas. Into faraway communities where, when snow lay in drifts over Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and Derbyshire, heat would be rising from parched grass or dust would be blowing in willy-willies. Where names newly chiselled into monuments topped by a statue of a World War I digger would glint more brightly than the heroes of Anzac. For a time. Until they too were faded, lichened. Names. Not men driving tractors across wide paddocks. Or standing in front of classes of upturned faces. Out on a cricket pitch on a Saturday afternoon. Taking their sons fishing. Or their daughters to ballet lessons. Sitting on the verandah with their wives, watching the sunset, talking about the future.

David still had many places on his must-see, must-do list, so after days listening to POW stories, it was a relief to take time out to visit Windsor Castle with Pop, and Runnymede, where Magna Carta was signed. ‘Another seminal site in the history of England that I’ve now seen!’ he exclaimed.

When he met his cousin Eric, back from almost two years in the Middle East, they made the trip into Hampshire together to visit Mattingley. They were thrilled to discover a picture-book village with charming thatched cottages clustered around the green and a 13th century church. Well pleased with their excursion into family history, they quaffed a pint in the Leather Bottle Inn.

In Nottingham catching up with Des, David fulfilled another long-held wish. Wandering among the great oak trees in Sherwood Forest, he said to Des, ‘I’ve always wanted to come here. Do you remember we did Robin Hood as a play in primary school?’

‘How could I forget?’ Des replied. ‘You were Robin Hood!’

‘And now you’re a Merry Man indeed, with your Maid Marian,’ David teased his old friend about his local lass, Sheila. But as he scuffled through last year’s leaves and rolled silken-smooth acorns in the palm of his war-damaged hand, he wondered, not for the first time, if he would ever find his own Maid Marian.

Reg Watson and David enjoying leave in Wales

A concert at London’s Albert Hall was a highlight, and David was able to write home that he was standing only a few feet from the Queen and the Princesses. But he told his parents nothing of his private grief as he had listened to the celebrated pianist Dame Myra Hess, knowing that he would never again be able to play.

One memorable day, after collecting eleven parcels at the Base Post Office at Kodak House he calculated that his mother alone had sent him more than seventy parcels, over one third of a ton of food! ‘But I must write and tell everyone not to send any more,’ he reminded himself. ‘They mightn’t arrive before I sail for home.’

Sailing for home. It was in all their thoughts. In all their conversations. But David hoped his embarkation call would not come just yet. He had signed up for a week’s British Council course in Stratford-upon-Avon, a week at Cambridge University, and a month at Oxford University. And he was keen to do them.

Back at Scampton, it was time to pack up yet again. As David surveyed all that he had accumulated since his last move, he consoled himself that he did not have a frying pan to pack, as did his Irish crew member!

But the letters… Oh, the letters. Although he had always discarded most after answering them, there were still too many to keep and he would have to discard more. Sitting on his bed, he began re-reading them, smiling, chuckling, blinking away tears. He would have to destroy those from his parents. But he wanted to keep the many messages of congratulation and well wishes for his recovery. From Drew and the rest of the crew. And the Wingco and the padre. And the last letters. He bit his lips as he picked up envelopes with the familiar handwriting of Frank, Peter, Tas and others. This was not the time to read them. Later. Much later. Perhaps when his heart was stronger again.

On the last night everyone joined in a farewell party in the Mess and eventually they made their way to bed at 4 am. ‘What a night! It’s a party we’ll all remember.’

More farewells were yet to be said before leaving next day for Gamston, the base where all Australians in Bomber Command had to hand in their surplus gear and be processed for repatriation. Twelve hundred men had already been through since VE Day, and had gone on to Brighton to await embarkation. The air was tense with expectation and excitement, loud with laughter, greetings and cries of ‘Australia, here we come!’ ‘And I’m drooling at the thought of lemon meringue pies again!’ Birdy crowed.

David met up with Drew, Pop and Boz and others. Drew was counting the days till he might see his Thel, but Boz was trying to get his time in Britain extended, to be as long as possible with his English Ann.

David was pleased that he and Pop had managed to get their departure deferred. But sad indeed to wave goodbye to Drew, who shouted ‘Bomb doors closed!’ and gave his usual cheeky thumbs-up sign as the bus pulled away through the station gates and passed out of sight. No longer would it be ‘Enemy coast ahead’ for him, but ‘Australia ahoy!’

Entry in David’s diary for 15 August 1945, describing Victory celebrations in Oxford. Entry in open diary below describes his first impressions of New York on 15 August 1943.