Death’s no respecter in this unjust spring, No chooser under the callous rain: but, brothers, All is won when men who find a cause to die for, live.

John Pudney, ‘Spring’, 1942

Back in Tasmania, David visited more families he knew whose sons did not return. Then, after some very welcome home leave, he had to go to Heidelberg Military Hospital in Melbourne for further tests prior to discharge. He was finally demobilised in January 1947, four and a half years after enlistment. Twenty months after VE Day, 17 months after VJ Day, David’s war was over. Officially. But its marks have remained for over sixty years.

During these years, David has paid three more instalments of the cost of his years as a pilot. While he was still at university in Tasmania he had to return to the Repatriation Hospital in Hobart for six months, delaying the completion of his Arts degree by a year. Then his fledgling career in Commonwealth Archives was brought to a close by another period of war-related illness.

David and I met at the University of Tasmania in March 1948. He was a few months off 26, a Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme Student in his second year. I was a fresher, just over 16 years old.

He was one of the few students on campus who had a car. But it was the man, not the car, to whom I was instantly attracted. Tall, good-looking, in his grey Savile Row suit, and grey and green tie from Burlington Arcade, he stood out.

First appearances did not lead to disappointment. He proved to be quietly spoken, courteous and chivalrous, thoughtful, with a wisdom even beyond his more mature years. And his sense of humour was most endearing. We began to meet regularly in the morning when our timetables allowed, to walk downtown for coffee. One day David told me that he would not be able to meet me next morning. I knew it was not because of lectures, but he gave no explanation. For two days and nights I wondered if it was the end of our friendship.

Then at breakfast on the third day, my mother, reading the Mercury, exclaimed, ‘David Mattingley was invested with the Distinguished Flying Cross at Government House yesterday morning!’

Our friendship deepened and five years later we were married.

My parents liked and respected David immensely but were concerned about his health record and its possible future effects. So they insisted that I should acquire professional qualifications beyond my degree before we married. Our marriage took place in December 1953 and we went off to David’s beloved England, thinking we might settle and make our life there. But with ‘only a colonial degree’, an appointment to the sort of school where David wanted to teach was not easy to obtain, and the pay was minimal, less than half of what he could earn in Australia. After some short-term contracts including a year at Marlborough College, we regretfully decided that it was better for us to return to Australia to raise a family.

But we had had almost two years to see some of Britain. We renewed some of David’s wartime friendships. In London David bought books on British, German, French and Russian history at Bumpus’ Bookshop in Oxford Street. We visited the RAF Memorial at Runnymede, where airmen with no known grave, including Hugh Brodie, are commemorated. We went to Lincoln and even drove along the deserted runways at Kelstern, now reverted to farmland. We made a pilgrimage to the ancient cathedral of St David’s in Wales, where the jackdaws chuckled and swooped round the squat grey building, laboriously built stone by stone so long ago to the glory of God. We explored quite a lot of Europe, where the effects of war were still painfully evident in many places. The great cemeteries of World War I spread over the fertile fields of northern France were especially moving. And shocking.

In 1960, before the birth of our second child, David paid the final instalment of the cost of being a pilot and was out of action for most of my pregnancy. In all, his war participation has cost him almost three years in hospitals. But throughout bad times and good his faith has upheld him. We have worshipped in our parish church, St David’s,

Burnside, for 49 years. In 1989 he attended a 625 Squadron reunion at Scampton and at the Squadron memorial at Kelstern, and in London was delighted to see St Clement Dane’s beautifully restored as the Royal Air Force church. We also visited Harewood House and Lincoln Cathedral, where we spent some time in the Airmen’s Chapel. Later, realising the ongoing need for support for the cathedral’s restoration, and how much it meant to David, I made him a life member of the Friends of Lincoln Cathedral.

David gave devoted service for 32 years, teaching English and Modern European history and coaching rowing at Prince Alfred College, Adelaide. He also wrote a small book on two of his heroes, both Lincolnshire men, Matthew Flinders and George Bass. (Matthew Flinders and George Bass, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1961, reprinted 1971).

On his long-service leave in 1974 we took our three children to Europe so that they might learn something of their English heritage and other cultures too, experiencing what it was like to be a foreigner, and hopefully becoming world citizens. Subsequently they have all returned to Europe. Two worked for many years in other countries and married partners from South Africa and Sweden. We have visited Germany a number of times, lived there for several months in the 1970s and have many good German friends.

Since 1958, David has been active in the Australian Institute of International Affairs and the University of Adelaide has named a prize in his honour. He has maintained his involvement with Community Aid Abroad (now Oxfam), since we started the South Australian arm of the organisation in 1964.

Sadly, he lost touch with the McNeill family after a letter in 1968 was returned ‘No longer at this address’, and also with the Bailey family after taking our children to visit in 1974. Mrs Bailey was in ill-health, but ‘held on so that she could see David again’. She died soon afterwards. Since beginning work on this project we have managed to re-establish links to both families by writing letters to the local newspapers in Kent and East Lothian, and this has been a great joy.

At the baptism of each of our three children, David’s mother wore the suit made from the Scottish tweed he had bought for her. At his 80th birthday party in 2002 we used the handmade lace tablecloth he had bought for her in Ceylon on his way back to Australia in 1946.

On the eve of our 50th wedding anniversary in December 2003 we were present at the unveiling of G for George, the newly restored Lancaster at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, where the sound and light recreation of an operation over Germany reduced veterans to tears. We placed scarlet poppies by seven names on the Wall of Honour and in the late afternoon sun we stood in the Court of Remembrance as it echoed with the sound of the Last Post. We remembered. And gave thanks.

On the day I was finishing the last chapter, the Sunday psalm proclaimed:

Though I walk in the midst of danger yet will you preserve my life: you will stretch out your hand against the fury of my enemies and your right hand shall save me. The Lord will complete his purpose for me. Psalm 138: 7-8a.

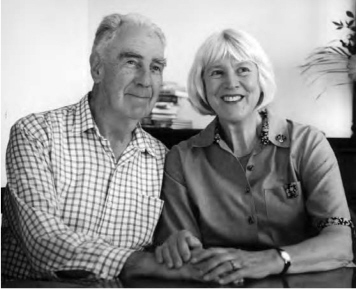

David and Christobel while working on this story