… never seen except when feared …

Don’t forget: they hit the streets …

—Léo Ferré, Les anarchistes

The Black Blocs are today’s best political philosophers.

—Nicolas Tavaglione

One day, history will vindicate us.

—Black Bloc participant, Toronto, June 2010

Amid clouds of tear gas, police officers in full riot gear face off with silhouetted figures bustling in the street. Masked and dressed in black, those figures are the “Black Bloc.” The black flag of anarchism waves above the commotion as bottles, rocks, and even the occasional Molotov cocktail fly overhead. The police fire volleys of tear gas and rubber bullets. Sometimes the bullets are real. The action unfolds against a backdrop of banks and multinational retail shops smeared with anarchist and anti-capitalist graffiti, their windows shattered. Since the epic “Battle of Seattle,” fought on November 30, 1999, during the meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the media have enthusiastically captured such scenes.

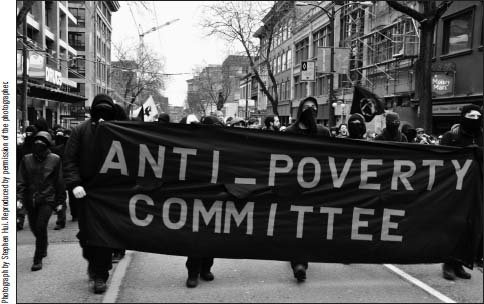

According to a widespread myth, there is only one Black Bloc, which is thought to be a single permanent organization with numerous branches throughout the world. In fact, the term Black Bloc represents a shifting, ephemeral reality. Black Blocs are composed of ad hoc assemblages of individuals or affinity groups that last for the duration of a march or rally. The expression designates a specific type of collective action, a tactic that consists in forming a mobile bloc in which all individuals retain their anonymity thanks in part to their masks and head-to-toe black clothing. Black Blocs may occasionally use force to express their outlook in a demonstration, but more often than not they are content to march peacefully. The primary objective of a Black Bloc is to embody within the demonstration a radical critique of the economic and political system. Metaphorically speaking, it is a huge black flag made up of living bodies, flying in the heart of a demonstration. As one activist put it, “the Black Bloc is our banner.”1 To make their message more explicit, Black Blocs generally display a number of anarchist flags (black or red and black) and banners bearing anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian slogans.

The Black Bloc tactic allows individuals to retain their anonymity by wearing masks and head-to-toe black clothing. May 1, 2013, Berlin.

There is no social body organized on a permanent basis that answers or lays claim to the name Black Bloc, although on occasion people involved in a Black Bloc have released an anonymous communiqué after a protest to explain and justify their deeds. More recently, in 2013, Facebook pages associated with the Black Blocs in Egypt and in Brazil offered explanations about civil disobedience, justifications for resorting to force in street protests, and criticisms of the structural violence of capitalism and the state system.

Voices decrying the “theoretical confusion” and “theoretical poverty” of Black Blocs and their allies can be heard even on the far left.2 But this sort of criticism is specious, because it assesses the theoretical value of direct actions using criteria that are foreign to such gestures, comparing them, for instance, to treatises of social or political philosophy. For many of its participants, the Black Bloc tactic enables them to express a world view and a radical rebuke of the political and economic system, yet they are certainly not so credulous as to believe that doing so can frame a general theory of liberal society and globalization. The Black Bloc is not a treatise in political philosophy, let alone a strategy; it is a tactic. A tactic is not about global power relations, or about how to take power, or even better, how to get rid of power and domination. A tactic is not about global revolution. Does this imply renouncing political thinking and action? No. A tactic such as the Black Bloc is a way of behaving in street protests. It may help empower the people protesting in the street, by giving them the opportunity to express a radical critique of the system, or by strengthening their ability to resist the police’s assaults on the people.

By and large, the men and women who take part in Black Blocs assign a clear political meaning to their direct actions. Their tactic, when it involves the use of force, enables them to show the “public” that neither private property nor the state, as represented by the police, is sacred, and to indicate that some are prepared to put themselves in harm’s way to express their anger against capitalism or the state, or their solidarity with those most disadvantaged by the system. A woman who had participated in many Black Blocs told me their actions against businesses and media vehicles are designed “to show we don’t want companies and media with unbelievable profit rates and that benefit from free trade at the expense of the population.”3 The Black Bloc type of action falls largely within the bounds of the media spectacle, inasmuch as it strives to introduce a counter-spectacle, albeit one somehow dependent on the official spectacle and public and private media.4 A participant in a Black Bloc in Toronto in 2010 put it this way: “The Black Bloc will not make the revolution. It would be naive to think that, in itself, the selective targeting of private property can change things. It remains propaganda of the deed.”5

A Black Bloc can vary in size from a few individuals to hundreds. During the Quebec student strike of 2012, it was not uncommon for people to refer to a lone individual wearing the appropriate outfit as “a Black Bloc.” In some cases, several Black Blocs are at work simultaneously during a single event. This happened, for example, at the marches protesting the Quebec City Summit of the Americas in April 2001. The largest Black Blocs are still found in Germany, where the participants number from a few hundred to several thousand. In principle, anyone dressed in black can join the black contingent. At the “anti-cuts” marches held in London on March 31, 2011, one member of the Black Bloc explained: “We had no idea of the numbers before the event on Saturday, and no idea it would be so radical in its actions. The black bloc idea spread like a ripple through the march. As people saw others in black, they changed into black themselves. Some marchers even left the protest to buy black clothing.”6 That said, calls to form a Black Bloc are sometimes sent out into cyberspace as part of a major mobilization, as was the case ahead of the 2001 Summit of the Americas, or by means of wall posters, as in Berlin before May Day of 2013. For very important events, affinity groups may meet hours or days before a demonstration to plan and co-ordinate their actions, and co-ordination meetings held weeks or even months in advance are not unheard of. It is far more common, however, for Black Blocs to emerge spontaneously.

A Black Bloc at the anti-cut protest in Trafalgar Square, London, UK, March 26, 2011.

“Wearing black allows you to strike and then fall back into the Black Bloc, where you’re always just one among many,”7 a veteran of various Black Blocs explains, noting that anonymity makes it possible to partly thwart surveillance by the police, who film all demonstrations and who requisition images from the media to identify, arrest, and subpoena “vandals.”8 Depending on the situation, the same activist adds, people involved in direct actions may also choose to “disperse, change clothes, and vanish amid the crowd.” This tactic, which proved effective in the follow-ups to the Battle of Seattle, has today lost some of its surprise effect, making it easier for the police to repress or manipulate demonstrators who employ it. Nevertheless, it can still be effective at times, because, for one thing, the police and security services are not all-powerful and all-controlling.

By 2002, after a number of spectacular events in Washington, Prague, Göteborg, Quebec City, and Genoa, activists like Severino, a member of the Bostonian Barricada Collective of the Northeastern Federation of Anarcho-Communists (NEFAC), were wondering whether “the Black Bloc tactic [had] reached the end of its usefulness.”9 In response to the intense repression following the 9/11 attacks on the United States in 2001, to the relocation of the major international summits to inaccessible venues, and to the outlawing of rallies, others bluntly declared, “the Black Bloc is dead.”10

Notwithstanding these announcements of its demise, the Black Bloc has revived itself a number of times over the past few years. In September 2003, about a hundred Turkish anarchists organized into Black Blocs marched against “the system and war” on the streets of Ankara. At the end of the event they burned their flags before dispersing.11 In 2005, a Black Bloc was active in the protest against the G8 in Scotland. In 2007 a Black Bloc of several thousand individuals marched against the G8 in Heilingendamm/Rostock, Germany. Bank windows were broken, a police car vandalized, a Caterpillar office torched—no doubt because Caterpillar equipment was employed to forcibly displace Palestinian communities in Israeli-occupied territories12—and 400 police were injured.13 In the fall of 2008, a Black Bloc went into action in Vichy, France, during the European Union (EU) summit on immigration. Then on December 6, 2008, in Greece, following the death of a 15-year-old anarchist named Alexandros Grigoropoulos at the hands of the Athenian police in the Exarchia district, countrywide demonstrations, in which many Black Bloc contingents took part, often turned into riots. Solidarity marches were held in the Kreutzberg district of Berlin and in Hamburg, where a Black Bloc of several dozen people chanted, “Greece—it was murder! Resistance everywhere!” Similar scenarios played out in Barcelona, where bank windows were shattered; in Madrid, where a police station was attacked; and in Rome, where stones rained down on the Greek embassy.14 The next year, the Black Bloc tactic was deployed in Strasbourg, during the NATO Summit; in Poitiers, where a prison and some storefronts belonging to Bouygues Telecom were hit; in London, at the G20 (April); and in Pittsburgh, again at the G20 (September). A few months later, in February 2010, a Black Bloc was formed in Vancouver during a rally as part of the “No Olympic Games on Stolen Native Land” campaign. Windows of The Bay department store, a sponsor of the Games, were shattered. The same year, a Black Bloc fought the police during the May Day march in Zurich. Yet in 2010, during the meetings held to prepare for mobilizations against the G20 Summit in Toronto, anti-capitalist militants in Montreal suggested that the Black Bloc belonged to history and that it was time to move on.

Nevertheless, in Toronto, despite nearly a billion dollars spent on security, months of police infiltration efforts, and numerous preventive detentions, a Black Bloc of between 200 and 300 individuals, accompanied by about 1,000 demonstrators, managed to outmanoeuvre the police and smash dozens of display windows along the city’s commercial arteries.15 Within barely an hour, the Black Bloc struck banks and financial services outlets (CIBC, Scotiabank, Western Union), multinational telecommunications conglomerates (Rogers, Bell), fast food chains (McDonald’s, Starbucks, Tim Hortons), clothing companies (Foot Locker, Urban Outfitters, American Apparel), and an entertainment corporation (HMV),16 not to mention media vehicles (including those of the CBC) and police property (the Police Museum and four police cars were set on fire, though not all of them by the Black Bloc17). Many Torontonians criticized these actions because some small businesses, such as the Horseshoe Tavern and Urbane Cyclist, also sustained damage, apparently for no political reason. By way of a feminist critique, the Zanzibar strip bar was also targeted.18 A sign over the front entrance had read, “175 sexy dancers—Forget G8 Try G-strings—G20 leaders solve world peace in our VIP rooms.”19 Speaking to a journalist, a protester explained: “This is all part of the sexist, male-dominated war machine we live in.”20 For activists, the political significance of these actions was unmistakable. “This isn’t violence,” said one. “This is vandalism against violent corporations. We did not hurt anybody. They are the ones hurting people.”21

Heart Attack protest against the 2010 Olympics, West Hastings Street, Vancouver, Canada, February 13, 2010.

In the wake of the Toronto G20 Summit, Black Blocs arose during the anti-austerity mobilizations in London (March 2011); a small Black Bloc was mobilized against the G8 in Deauville, France (May 2011); and a much larger one was formed as part of the “No TAV” movement opposing the construction of a high-speed rail line in the Val di Susa, Italy (July 2011). In September 2011, a Black Bloc took part in the annual human rights march in Tel Aviv. The Occupy Movement, which had put up tents in a number of Western cities in the fall of 2011, called for demonstrations in October of that year. Black Blocs appeared during Occupy rallies in Oakland, where actions were carried out against the Chase Bank, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Whole Foods Market, and the office of the president of the University of California. Meanwhile, in Rome, Black Blocs targeted several banks and dozens of police officers were injured. In 2012, Black Blocs were seen during the largest and longest student strike in the history of Quebec. There was also a Black Bloc on March 29, 2012, at a general strike against labour law reforms on Plaza Catalunya in Barcelona, and another at a mass rally in Mexico City protesting the inauguration of the new president. Black Blocs were active as well in Greece during the wave of protests against austerity policies. In January 2013 a group calling itself “Black Bloc” (in English) appeared among the demonstrators in Egypt. According to the BBC,

Black Bloc activists march during the annual human rights march in Tel Aviv, December 9, 2011.

members of the group appeared in Tahrir Square on 25 January, banging drums and saying they would “continue the revolution” and “defend protesters” … The Black Bloc describes itself as a group that is “striving to liberate people, end corruption and bring down tyrants” … Filmed at night, short video shows men wearing black clothes and black masks. Some hold the Egyptian flag while others carry black flags with an “A” sign—an international symbol of anarchism.22

In addition, Black Blocs were present at May Day marches in Montreal and Seattle, and a small-scale Black Bloc had confronted the police at the demonstrations against the Chicago NATO summit in May 2012. Finally, in Brazil during the summer of 2013, Black Blocs were involved in street protests in Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, and Belo Horizonte, during the social unrest against the high cost of living.

The black-clad activists known as Black Blocs are not the only masked protesters to be found taking part in contemporary political riots and confrontational demonstrations. Palestinian youths, their faces wrapped in the traditional keffiyeh, and armed with no more than stones, have been confronting Israeli soldiers for many years. In Latin America, young encapuchados (hooded ones) have long battled with police—for example, during the student mobilizations in Chile.23 That said, the Black Bloc has drawn special attention and constituted itself as a distinct political subject, in part thanks to its unique aesthetic, but also because it has been associated somewhat indiscriminately with anarchy and destructive irrationality. For instance, a Toronto Star report on the mass rally against the G20 identified “anarchists from the notorious Black Blocs,” specifying that there were “about 100 Black Bloc anarchists in head-to-foot black clothing, leading an angry mob of about 300 … destroying store fronts and generally creating the kind of havoc they’re known for at G8 and G20 summits worldwide.”24

The fascination with the Black Bloc is such that it has become a “newsworthy” topic. On the day after the major anti-G20 demonstration in Toronto, the Toronto Star ran the headline, “Behind the Black Bloc: G20 Violence.” A day later, the same newspaper ran a piece titled “Who is the Black Bloc?” When the Black Bloc first appeared in Egypt, in January 2013, the news was covered by the Canadian, French, German, British, Japanese, Israeli, Spanish, Swiss, Tunisian, and US media. In Brazil, there was such a fuss about the Black Bloc that in August 2013 the progressive magazine Carta Capital polled its readers with this question: “The Black Bloc, an anti-establishment form of protest, resorts to destruction against banks and stores. What do you think about that? (1) I am against all vandalism at all times. (2) I am in favour of it in the case of stores, if nobody is hurt.” The result? 11,835 people answered, 7,793 (66 percent) in favour of the Black Bloc’s actions.25

Very often, the English words “Black Bloc” are borrowed by other languages. For instance, in Brazil in 2013, the media ran headlines such as “Conheça a estratégia ‘Black Bloc,’ que influencia protestos no Brasil” (Discover the “Black Bloc” strategy that influenced the demonstrators in Brazil [G1 Globo, July 12, 2013]), and “Para especialistas, ideario ‘black bloc’ permanecera ativo” (Specialists say the ideology “black bloc” remains active [Folha de S.Paulo, August 4, 2013]).26 In Italy on July 4, 2011, following the mobilization of the No TAV movement, newspapers carried front-page headlines such as these: “TAV, guerriglia dei black bloc” (TAV, Black Bloc guerrilla [Rome edition of Metro]); “I black bloc contro il cantiere” (Black Bloc against the construction site [Corriere della Sera]); and “I black bloc armati venuti de lontano” (Armed Black Blocs come from afar [La epubblica]).27 Yet some newspapers prefer to translate the English designation into the local language, as when the phrase “Bloque negro” appeared in an El Pais report on the protest rallies held in December 2012 at the presidential palace in Mexico City.28 In Greece, the media and the state coined the term “Koukoulofori” (the hooded ones).

In the weeks and days preceding international summits and other important events, articles in the media focus on the Black Blocs, depicting them, for instance, as “the anarchists who could be the biggest … security threat.”29 When a Black Bloc goes into action, the media’s response often follows a recognizable pattern. The same evening or the next morning, editorialists, columnists, and reporters rail against the Black Bloc troublemakers, branding them “thugs.” The following day, however, the tone generally becomes more neutral. Readers are informed that anarchists are behind the tactics involving weapons such as rocks, clubs, slingshots, and Molotov cocktails, as well as the use of shields and helmets for defensive purposes. Such articles sometimes allude to major Black Blocs of the past. Then some academics are quoted, as well as representatives of the police and spokespersons for institutionalized social movements, who dissociate themselves from the “vandals.” At best, the journalist quotes some participants in the Black Bloc, who then have a chance to speak for themselves and to explain why they do what they do.

Media references to the Black Bloc are sometimes freely adapted for a variety of situations. During the 2012 student strike in Quebec, allusions to the Black Bloc became so commonplace that the term popped up in a column on environmental issues. Deriding the spread of camouflage designs in outdoor apparel, the columnist claimed this makes “rabbits, raccoons, foxes, partridges, and deer scatter like Black Bloc members catching sight of the paddy wagon.”30 In a more serious vein, the disturbances provoked by the Black Bloc at the 2007 G8 were compared by some German media to the positions of certain participants in the official Summit. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, for example, reported that “the Black Bloc isn’t the only group to use this monstrously big annual event as an opportunity to make an impression on the public. Two participants, the American and Russian presidents, already tried to do this by arriving in an unusual way.”31

The Black Bloc has even become a cultural icon. It has been represented, for instance, in various films. Predictably, the Black Bloc shows up in the 2007 fictional film Battle in Seattle, directed by Stuart Townsend. In one sequence a demonstrator shatters the display window of a large store, behind which two female shoppers are talking. Having gotten over her initial surprise, one of the women challenges him: “What are you doing? This woman is pregnant!” He snaps back, “Oh, yeah, you’re going to have a kid? … And you want your kid to work to death in a sweatshop making baby clothes?” “Of course not,” the pregnant woman answers. “So don’t fucking shop here!” the man yells, before scurrying away. In the next scene a member of the Black Bloc is taken to task by a man and woman who support nonviolent civil disobedience. The ensuing heated debate on violence and the media ends in a scuffle, with the Black Bloc member finally running off to join his comrades. Another instance is the sixth episode of the 2012 season of Continuum, a second-rate sci-fi television series, which opens with a scene of pillaging set in the distant future. The pillagers seem to be part of a Black Bloc. A female member of the anti-riot squad laments, “What a waste … They call themselves revolutionaries but all I see is vandalism, with no respect for private property.” Her partner sighs, “If there is a message, I’m not getting it.” Later in the episode, the action, now back in the present, has a Black Bloc intruding on a protest rally at the headquarters of a corporation. An individual reviewing the video recording of the subsequent riot claims to recognize “a guy who I think may be leading the anarchists amongst the legitimate protesters.” The opening episode of the second season of the series XIII also includes a demonstration featuring a Black Bloc. In Cosmopolis, David Cronenberg’s film adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel, an anti-capitalist rally has all the trappings of a Black Bloc. A documentary directed by Carlo A. Bachschmidt and released in 2011 under the unadorned title Black Block—even though this subject is barely mentioned in the film—deals with the events at the 2001 G8 in Genoa. The Black Bloc has also become the subject of comic books32 and novels,33 such as Black Bloc, a French detective novel by Elsa Marpeau, published by Gallimard in 2012. In Brian Heagney’s ABCs of Anarchy (2010), a book for kids, the letter B “is for Black Bloc: A black bloc is a group of people dressed in black to represent either mass solidarity for a cause, or mass resistance to oppression.” In a more upscale mode, “Black Block” was the name of the gift shop (closed in 2012) in the contemporary art museum at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. On sale there were “I Love Black Block” badges and a fashion line including a pair of jeans priced at €240. As indicated on the shop’s website, “Blackblock offers clothes in a shop that invites regularly personalities from the world of art, fashion or music to use the space of Blackblock to create their universe.”34

Certain artists, rather than co-opting the Black Bloc image for commercial or entertainment purposes, use it to make a cogent social statement. This is what the visual artist Francesco di Santis did in the United States, when he produced a series of portraits of Black Bloc activists.35 Another example is Packard Jennings, an American West Coast artist, who in 2007 created an “Anarchist Action Figure,” a 40-centimetre-high figurine representing a young man dressed entirely in black and wearing a black hood. As part of the obvious reference to the Black Bloc, the “action figure” was boxed like a toy together with a few accessories: a gas mask, a jerry can, a paint bomb, and a Molotov cocktail. In addition to the title of the work, the box carried the slogan, “Arm your dissent!” Having deposited the package on the shelf of a toy store, the artist filmed the moment when a customer took it and went to pay for it at the cash register. The artist’s aim was to denounce the co-opting of images of radical protest for commercial purposes.36

Who Says What About the Black Blocs?

The public image of the Black Blocs has been skewed by the hatred and contempt harboured by their many critics: politicians, police officials, right-wing intellectuals, journalists, academics, the spokespersons for many institutionalized progressive organizations, and other protesters, who feel that they endanger people who are neither able nor prepared to deal with police violence.37 These detractors are united in denigrating the Black Blocs—or indeed any demonstrators who resort to physical force—portraying them as individuals bereft of political convictions and whose only purpose in joining a demonstration is to satisfy their craving for destruction. Quite often, they are also depicted as coming from afar—for example, from Eugene, Oregon, to protest against the WTO in Seattle, in 1999; from Germany to protest against the G8 in Genoa, in 2001; from Quebec to protest against the G20 in Toronto, in 2010; or from all around Europe, to protest against the TAV in Italy, in 2011.

This derogatory discourse is no surprise, coming from the police. In July 2011, following the disruptive demonstrations of the No TAV movement, police officials stated that “there were about three hundred Black Blocs who had come from Spain, France, Germany, and Austria” with the goal of generating “maximum violence against the authorities.” These activists were nothing but “delinquents and cowards” who were “well known to the police and [had] nothing to do with the Val di Susa issue.”38 In London, a few months earlier, Metropolitan Police commander Bob Broadhurst, commenting on the Black Bloc contingent in the “anti-cuts” march, had declared: “I wouldn’t call them protesters. They are engaging in criminal activities for their own ends.”39

Such statements are nothing new. Here, for example, is what Jean-Claude Sauterel, police spokesman in the Vaud district of France, told Le Figaro in June 2003, when the G8 leaders were meeting in Évian: “These people have come for the sole purpose of wreaking havoc.”40 His words seemed to echo the statement made ahead of the Summit of the Americas in April 2001 by Florent Gagné, director of the Sûreté du Québec (SQ, Quebec’s provincial police force), who said he was concerned about “the so-called direct action groups. These are violent groups with no real ideology. They are vandals, anarchists.”41 That same year, a report by the Office fédéral suisse de la police titled “The potential for violence residing in the antiglobalization movement” was similarly dismissive:

It is difficult, moreover, to grasp the potential for violence currently displayed by certain youths. Such violence often comes in the shape of a destructive frenzy, apparently unprovoked, or of extreme aggressiveness toward others. Consequently, public events, whatever they may be, are increasingly marred by acts of vandalism devoid of any political or ideological justification.42

Explicitly denied here is the political nature of such direct actions, which are thereby cast out beyond the pale of political rationality.

Like the police, politicians attempt to divest the “vandals” of all political reasoning. During the G20 meeting in Toronto, a comment on the website of Canada’s left-of-centre political party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), called on progressives to denounce “the Black Bloc thugs. They are not fighting for social justice, they are criminals looking for an excuse to be criminals … A thug is a thug, regardless of their rhetoric.”43 Such criticism sometimes emanates from the upper echelons of the state. In March 2011, following the “anti-cuts” demonstrations in London, British Home Secretary Theresa May said: “I want to condemn in the strongest terms the mindless behaviour of the thugs responsible for the violence.”44 London’s Deputy Mayor Kit Malthouse compared the Black Bloc to “fascist agitators,” adding that “they were a nasty bunch of black-shirted thugs and it was pretty obvious they were intent on rampaging around and would be difficult to control.”45 In 2010, in the wake of the Toronto G20 Summit, Dimitri Soudas, then head of communications for the Prime Minister of Canada, appealed to patriotic sentiments, declaring that “the thugs that prompted violence earlier today represent in no way, shape or form the Canadian way of life.”46 Already in the early 2000s, politicians were depicting Black Bloc actions as completely lacking in political significance. “I exclude the vandals,” said Guy Verhofstadt, the Prime Minister of Belgium and President of the EU, with reference to the G8 Summit in Genoa in July 2001. “They do not express an opinion. They seek violence and that has nothing to do with the G8.”47 German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, speaking on the same occasion, declared: “It is futile to dialogue with those who have no political beliefs.”48 Meanwhile, the Prime Minister of Canada, Jean Chrétien, stated bluntly that “if the anarchists want to destroy democracy, we won’t let them.”49

Apparently convinced that the Black Blocs have nothing to do with politics, both police officials and politicians have claimed either that they are composed of hooligans, sports fans who surge out of the stadiums and instigate riots (as happened in Rome on the occasion of an Occupy rally in October 201150), or that, on the contrary, sports riots are triggered by anarchists whose only goal is to destroy everything, whatever the occasion. Thus, in 2011, commenting on the riot that had erupted after a defeat of Vancouver’s professional hockey team, the Canucks, police chief Jim Chu declared that the rioters were “criminals, anarchists and thugs who came to town bent on destruction and mayhem,” terms that would be echoed by the city’s mayor, Gregor Robertson, when he pinned the blame for the riot on “anarchists and thugs.”51 Later, however, Chu was obliged to admit he had erred and that anarchists had in no way been involved in the hockey riot.52

Journalists are no exception to the rule whereby the actions of “vandals” must be denied any political dimension. Indeed, they sometimes indulge in sneering, categorical value judgments about the Black Blocs and their allies. After the May Day protest of 2012, the Berlin Kurier, under the headline “The Hour of the Idiot-Rioters,” ran an article that stated: “These hateful fans of chaos [were ready] for rioting and wreckage. They wanted at all cost to do battle in the street!”53 In 2010, the Toronto Sun published a commentary about the G20 demonstrations. This columnist enlisted an “expert” to help readers distinguish between rioters and “real protesters, with a real cause, and real concerns”:

In a perfect world, the protests would go on peacefully, people would make their point, whatever the heck that might be, and all would be fine … As security expert John Thompson of the Mackenzie Institute54 told me before the summit, there’s 2% of the crowd who are there for the criminal free-for-all, with no cause at all.55

In an interview with another newspaper, the same John Thompson described people participating in a Black Bloc as “adrenaline junkies … What the Black Bloc protesters do is basically an extreme sport at public expense.” In the same article, concerning the Black Bloc, Peter St. John, a University of Manitoba professor who “specialize[s] in security issues,” opined that “when you start using violence, you’re really coming under the rubric of a terrorist organization.”56

Regarding the Black Bloc in Egypt, an Al Jazeera article in Arabic reported, on the basis of information from an “anonymous source,” that this group had been trained in a military zone of the Negev Desert and was believed to be operating under the supervision of active or retired Israeli secret service officers assisted by Israeli military experts in security and psychology. According to Ibrahim al Brawi, the director of the Palestinian Studies Centre in Cairo, the Egyptian Black Bloc was linked to a global network of human rights organizations and Western security companies and was dedicated to overthrowing the regime.57 These assertions sound like the figments of highly paranoid imaginations; nevertheless, they have helped construct the public perception of the Black Bloc as a shadowy menace.

The mainstream media consistently describe most demonstrators who resort to force as “very young.”58 Frequent variations include “young extremists,”59 “young hotheads,”60 and “young vandals.”61 This line of vilification has been a staple among media professionals since the early 2000s, as illustrated by an Agence France-Presse article asserting that the aim of the “vandals” at Genoa in 2001 was “to destroy everything,” and, moreover, that they constituted—as the left-wing intellectual Chris Hedges would echo a few years later—“a veritable cancer within the movement.”62 Regarding the demonstrations in Genoa, French TV news viewers were informed that “the sole objective [of] the notorious Black Blocs,” composed of “ultraviolent anarchists” and other “extremists” (who were “thirsting for violence and destruction”), was to “globalize their hate and violence.”63 Five journalists of the French magazine L’Express managed to condense into a few lines all the clichés concerning the Black Blocs: “Their discourse, at any rate, is that of anarchism. They advocate the use of violence against anything representing a form of state organization.” Rehearsing the stereotypes one by one, the Express team observed that “more and more young, somewhat confused Americans” were getting sucked into the Black Bloc phenomenon and eventually involved in demonstrations, “not so much to protest and oppose as to smash and burn.”64

Journalists also relay the opinions of “ordinary” citizens and “nonviolent” demonstrators who disapprove of the use of force. After the 2001 G8, for example, an anonymous resident of Genoa remarked that the “vandals and radicals” had “no specific target in view but simply wanted to destroy things.”65 In another instance, “a sympathiser of the movement” was quoted: “Those people have no political ideas. They represent no one and can be compared to hooligans.”66 Similarly, a reporter covering the demonstrations against the G8 held in France in June 2003 quoted an activist and passed judgement on the Black Bloc at the same time: “Summing up the situation, a sincere alter-globalization activist dismayed by the disturbances at the marches observed, ‘They are motivated only by destruction and vandalism.’ The same individual added angrily, ‘They are just some little idiots who came to smash windows for the fun of it.’”67

Although some spokespersons for mainstream social democratic institutions, such as socialist parties and trade unions,68 have censured both police violence and the brutality of capitalism, their attacks against the Black Blocs are not unlike those launched by police officials and centrist or rightist politicians. Yvette Cooper, a British Labour MP, when remarking on the above-mentioned events in London, denounced the “few hundred mindless idiots [for engaging in] thuggish behaviour of the worst kind.”69 Chris Hedges, a progressive antiwar intellectual and writer well known in the United States, had this to say about the Occupy Movement’s call for demonstrations in November 2011: “The Black Bloc anarchists, who have been active in the streets in Oakland and other cities, are the cancer of the Occupy movement … They confuse acts of petty vandalism and repellent cynicism with revolution … There is a word for this—‘criminals.’”70 During the Toronto G20 Summit in 2010, Jack Layton, the leader of Canada’s left-leaning New Democratic Party, stated that “vandalism is criminal and totally unacceptable” and expressed the hope that order would be quickly restored for the sake of peaceful and respectful dialogue.71 Once again, this is nothing new. Susan George, vice-president of ATTAC, the Association pour la taxation des transactions financières et l’aide aux citoyens (Association for the taxation of financial transactions and aid to citizens), commenting on the demonstrations against the EU in Göteborg in 2001, said that “the violence of the anarchists or vandals is more antidemocratic than the institutions they are supposedly fighting against.”72

Voices on the far left have taken up the same refrain. The Communist Party of Canada and the Communist Party of Quebec have denounced the Black Bloc and anarchists for their “infantile foolishness” at the 2010 G20 Summit in Toronto, deriding the “childish black-bloc tactic.”73 In France, Rouge, the official organ of the Ligue communiste révolutionnaire (LCR), published unequivocal criticisms of the use of force during demonstrations in an article titled “‘Black Bloc,’ violence et intoxication.” The author, Léonce Aguirre, later associated with the alter-globalization Social Forum, began by declaring that he wished to avoid “the trap of the nice demonstrators on one side and the nasty vandals on the other.” Yet he then immediately launched a bald attack against the Black Blocs, arguing for an “uncompromising critique of the fantasy of a possible ‘military’ confrontation between a tiny minority and the state apparatus.”74

As a sidelight to all of this, it is worth quoting the Toronto priest who, addressing his Sunday congregation the day after the massive anti-G20 demonstration, condemned “the cowardice of those who hide behind masks, whether they be white hoods or black ones.”75

So we have come full circle, from the police officer and the politician to the communist commentator, with, along the way, the capitalist ideologue, the good protester, the spokesperson for progressive forces, the editorialist, the reporter, and the priest. All share the same sentiments and arrive at the same conclusions.

“Cancer,” “idiots,” “mindless thugs,” “anarchists,” “young bums,” “devoid of political beliefs,” “thirsting for violence,” “vandalism,” “cowardice” … Mere epithets under the guise of explanations? Perhaps. But words like these have very real political effects, because they rob a collective action of all credibility by reducing it to a vehicle for the supposedly brutal, irrational violence of young people.

Only one thing is missing from this unanimous chorus: the voices of those who have taken part in a Black Bloc.76 When we listen to them, the reality becomes more complex and more interesting, and the phenomenon—its origins, dynamics, and objectives—easier to understand. I do not claim to speak on behalf of the Black Blocs; anyone acquainted with the subject knows that such a claim would be absurd. My goal, rather, is to go back to the roots of the phenomenon and examine it on the basis of Black Bloc actions, many of which I have observed firsthand,77 communiqués (distributed primarily online),78 and interviews with participants who have been willing to share their experiences, be it with me or with professional journalists. All told, several dozen Black Blockers active in a number of countries have spoken out in these communiqués and interviews over some 15 years, often expressing themselves in very similar terms.

After retracing the history of the Black Bloc, describing how it functions, and analyzing its political motivations, we will be able to soberly assess the shortcomings of this type of collective action and its effects on social and political mobilizations and struggles. Furthermore, we will be able to grasp more fully the political consequences of the intense criticism to which the Black Blocs have been subjected, especially the ways in which that criticism has enhanced the legitimacy of the political and social elites at the expense of anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian protesters, thereby encouraging police repression.