chapter three

ready for war

Bootleg of the Stockholm show on February 17, 1984, with a photo of The Clash by Jan Bengtsson/Schlager magazine, and a photo of the Salvadoran military with victims.

The logical consequence of the preparation for nuclear war is nuclear war . . . If the world were to fall prey to such a disaster, we will take with us not only all present life, but the magnificent heritage [past generations] bequeathed . . . We hold in our hands the ability to destroy creation. It could happen any day.

—Helen Caldicott, Missile Envy, 1984

Every war, before it comes, is represented not as a war but as an act of self-defense against a homicidal maniac. The essential job is to get people to recognize war propaganda when they see it, especially when it is disguised as peace propaganda.

—George Orwell, 1937

A siren was screaming. Red lights were blinking on and off. It was just past midnight, September 26, 1983, deep in Serpukhov-15, a secret bunker outside Moscow. The message from the Soviet early warning system was clear: a nuclear missile attack from the United States was underway.

Stansilav Petrov—the lead officer on duty that night—froze in place. The unthinkable event he and his team had trained for appeared to be happening. “The siren howled, but I just sat there for a few seconds, staring at the big, backlit, red screen with the word ‘launch’ on it,” Petrov remembered years later.

The Oko alarm system was telling him that the level of reliability of that alert was “highest,” indicating there could be little doubt that America had launched a missile. “A minute later the siren went off again. The second missile was launched,” Petrov explained. “Then the third, and the fourth, and the fifth. Computers changed their alerts from ‘launch’ to ‘missile strike.’”

But something didn’t seem right. Why an attack with such a small number of missiles? The Soviets feared the Reagan administration intended a first strike, but if that was happening, there should be hundreds, maybe thousands of missiles in the air.

Knowing that his system was new and relatively untested, Petrov swiftly checked with colleagues staffing the radar early warning systems. No missiles had been sighted on their screens. Which assessment was right?

Petrov’s duty was to report this alert. Every second counted, given that US missiles, once launched, could reach Russia in minutes. He was, however, well aware that Soviet forces were on high alert, and that a false alarm might set off a cascade of nuclear dominoes that could end human life on earth as he knew it.

His career—and millions of lives—was on the line. Petrov made his decision, choosing not to report the alert up the chain of command. The next twenty minutes were agony, but when no missiles landed, Petrov knew he had been right.

It was later discovered that the “missile launch” had been simply sunlight reflected off the clouds, shockingly misinterpreted by the Oko system. In the twenty-first century, Petrov would be feted as “the man who saved the world” and September 26, 1983, would be “the day the world almost died.”

At the time, however, Petrov’s gutsy call resulted in a reprimand for disregarding protocol and subsequent early retirement. Nothing would be said publicly about the incident, which deeply embarrassed the Soviet military machine. Many years passed before anyone outside of the USSR’s nuclear program knew just how close the earth had come to annihilation due to mechanical error.

Petrov took it philosophically, loyal to his country but secure in the righteousness of his action. Meanwhile, the world continued to teeter on the abyss of nuclear holocaust, with most people blissfully, willfully unaware of the danger. Not everyone, however, was willing to accept this quietly, without words of protest.

Flash forward five months to Colston Hall in Bristol, England, 1,900 miles east of Moscow: named for Edward Colston, a well-known philanthropist who had made his money in the slave trade, this concert venue was packed with two thousand paying customers on the night of February 13, 1984.

The crowd was restless. The lead singer pacing back and forth in the spotlight—resplendent in a bright-red Mohawk—knew it. After sparring with some outspoken show-goers, the slender figure stepped to the front of the stage, defiant, eager to confront: “What you see here is one rat shouting . . .”

Few might guess that this man was identifying himself with one of the victims of the rat-catcher of Hamelin, the Pied Piper, who—legend has it—ended that town’s infestation by leading countless rodents to their deaths with his hypnotic music.

The hubbub continued unabated. The singer ignored the catcalls and continued on: “What you see here is one rat making his piteous moan!” As the crowd struggled to make sense of this, he unleashed a jarring denouement: “Okey-dokey, the Pied Piper of Hamelin can be found . . . I’ll be ready for war!”

With that, the four figures shrouded in shadow behind him sprang into action, hurtling into the light with sound and motion. The funky drums and clipped chords of “Are You Ready for War?” cut through the sweat- and cigarette-soaked air, and the “rat”—Joe Strummer—flung himself into the swirl of word and beat.

For reasons both topical and musical, “War” had come to sit early in the nouveau Clash set, usually in the third slot after “London Calling” and “Safe European Home.” The tune operated on multiple levels. Listeners might find their feet moving to the rhythm, and their minds opening to a frightening reality. This could be a song for those who wanted to both dance and riot.

“War” was made for this scary moment, speaking powerfully to the danger that faced the world in the early days of 1984. “Free your mind and your ass will follow” funk pioneer George Clinton had proclaimed more than a decade earlier. While this song sought the same kinetic connection with its audience, it offered not trippy idealism but urgent reality, targeting the Pied Pipers of world war.

The words were nursery-rhyme simple, but made their point: the nuclear competition between the US and USSR endangered the entire world. “No use running in a mobile home / everywhere is a target zone / hell is ringing / on a red, red phone.” There was no escape, only urgent confrontation. As Strummer said elsewhere at the time, “The atomic age is upon us already, it’s time to wake up!”

This “sea shanty,” as Nick Sheppard described it, sported an infectious beat with two guitars crunching and slicing in quick succession—a spoonful of sugar to make the bitter medicine go down. When the song asked, “Are you ready for war?” it was a cautionary tale about possible destruction and a call to arms.

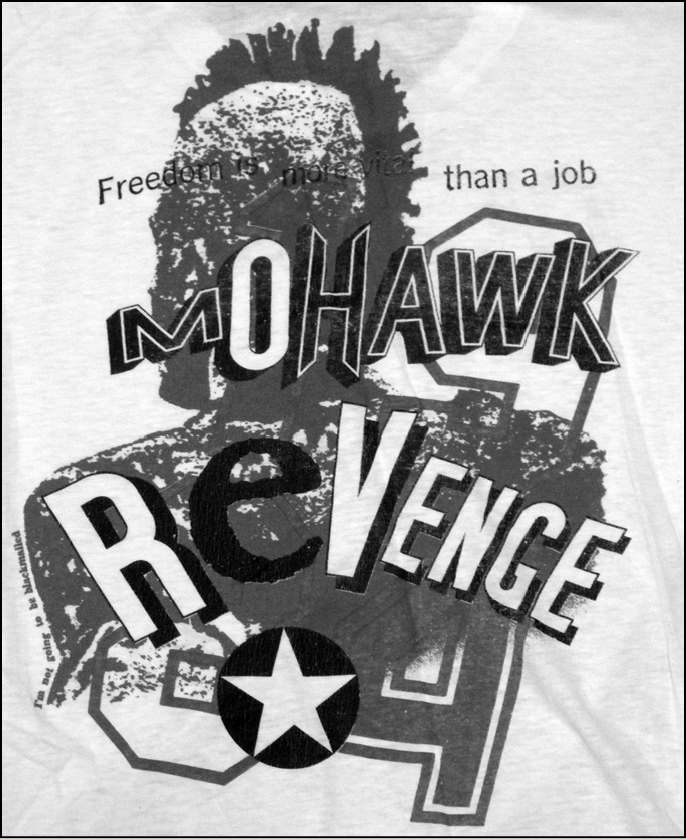

Onstage, Strummer wore a T-shirt designed by longtime Clash ally Eddie King that went well with his new hairdo. Mohawk Revenge, the shirt proclaimed, with an anonymous Mohawked punk and ghostly 1984 hovering in the background. The actual front of the shirt—Strummer wore it back to front—was equally striking. Two American paratroopers with hair trimmed into austere Mohawks stood face to face, evoking the infamous Sex Pistols “gay cowboys” shirt.

Instead of shocking with sexually graphic juxtaposition, however, this shirt suggested deadly serious resolve, for these men were preparing for the D-Day invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. The scene captured them grimly applying war paint to each other, with a giant boom box added by King as a backdrop.

Repurposing the Stars and Stripes photo as The Clash prepare for D-Day.

Freedom is more vital than a job, Mohawk Revenge, 1984. (Both T-shirts by Eddie King.)

First published in the US military journal Stars and Stripes in 1945, the photo had been brought to King’s attention by Paul Simonon some years earlier. “Kosmo knew me from when I worked next door to him at Stiff Records,” King recalls. “We became friends, and through him I met the rest of the band.”

King assisted Julian Balme with Combat Rock–era Clash graphics, designing T-shirts and record sleeves. King helped Balme turn one of Vinyl’s drawings into perhaps the most gripping and resonant of all Clash images: the words KNOW YOUR RIGHTS nestled beneath an open book with THE FUTURE IS UNWRITTEN written in bloody letters on one page, juxtaposed with a pistol-shaped hole on the other. The stark tableau was itself flanked by a large red star that evoked the band’s socialist orientation.

The new shirt had been a collaborative effort with roots stretching back to 1982. As King says, “Paul gave me a copy of the ‘Mohawked’ D-Day paratroopers and said, ‘Put this on a shirt!’” This motif had struck a chord within the Clash camp. Impressed by the vehemence of the Mohican-wearing Travis Bickle character in the film Taxi Driver, and unsettled by their pop breakthrough, first Vinyl and then Strummer adopted this militant look early in the Combat Rock era.

However, the shirt did not materialize immediately. “I did a sketchbook design using the photo and came up with the slogan Mohawk Revenge with the intention of producing a T-shirt,” King recalls, “but I never got around to it.” As the band drifted, paralyzed by internal divisions and the ambivalent impact of their Top 10 success, King moved on to other endeavors.

In late 1983, King was called up for a new tour of duty: “Bernard conducted an informal interview up in Camden. Flipping through my sketchbook, Kosmo spotted the design and said, ‘Can I show this to Joe?’ who was rehearsing across the road. Ten minutes later he came back: ‘Joe wants this on a T-shirt!’”

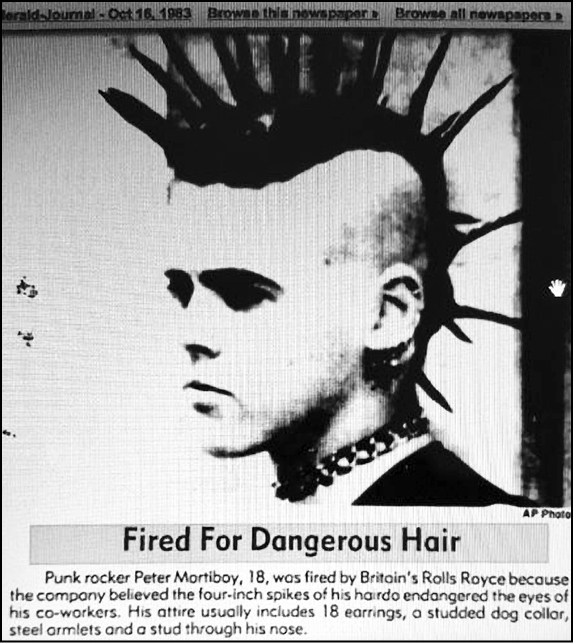

The motif gained yet another facet when the band read about Peter Mortiboy, an eighteen-year-old punk who was fired in late 1983 from his job at Rolls Royce. The cause of Mortiboy’s termination? His spiky Mohawk that—according to a Rolls Royce spokesperson—represented a “safety hazard.” Angered by this injustice, Vinyl and others in the Clash camp got involved helping Mortiboy.

Eddie King (in a photo by Nick Sheppard) created edgy, provocative graphics that complemented the neo-Clash’s raw style. His T-shirt for Mohawk Revenge (see previous image) used a photograph of the back of Peter Mortiboy’s head.

A newspaper clipping of Mortiboy. (Photographer unknown.)

While nothing ever came of plans mooted for a band or a record with Mortiboy, King designed a T-shirt as a tribute. It used an image of the back of Mortiboy’s head, with Mohawk Revenge as well as Freedom is more vital than a job juxtaposed with the photo. I’m not going to be blackmailed could also be glimpsed in small type on the edge of the image.

According to King, “Mohawk Revenge then became the theme as opposed to just a reference to the D-Day photo.” The slogan was multifaceted, he explains, drawing together “this Native American element, hardcore punk, and the military aspect, as well as this sense that an uprising is being attempted, a fight back.”

A deeply politicized artist, King was energized by his conversation with Rhodes and Vinyl, and eager to sign on to the new campaign: “Bernard really doesn’t like the way things are, he really, really does want a revolution! That inspired me, and I was excited to work on the shirt and anything else the band wanted.”

Clearly Strummer agreed, as the Mohawk Revenge shirt would almost always be on his chest for Clash shows over the next few months. With the front photo of the paratroopers now emblazoned with The Clash and Out of Control, the shirt suggested that the band found itself in its own D-Day moment.

While Europe, appropriately enough, was soon to come on the itinerary, The Clash followed its Barrowlands concert with dates in Manchester, Leicester, and Bristol. The shows quickly sold out, and audience reaction was strong, if not universally positive. While devotees of Mick Jones or British pop were likely unsatisfied, this rough-and-ready Clash was proving to be blisteringly good.

Given that it had less than two months under its belt, the band was on top of its game, and Strummer was in good spirits. The vocalist’s freshly cut Mohawk signaled confrontation, beginning with his own audience. In Leicester, he wrangled good-naturedly with some fans—including die-hard gobbers—and introduced himself as “Mick Jones” before “Are You Ready for War?”

Near the end of the set, shouting erupted in the crowd as Strummer announced “Tommy Gun.” The singer waved off the band and stopped to listen. Hearing a litany of Jones-related complaints, Strummer spoke gently: “Can I ask you one question? Who understands why we had to change?” When only a few people raised hands, he responded, “Well, that means I have to tell the rest of you . . .”

With that, Strummer’s voice shifted, rising from a conversational tone to a near scream: “The Clash was going nowhere—it was going to DIE! GOODBYE!” When this explanation failed to settle the matter, the singer challenged with biting humor: “What’s your contribution to the scheme of things? What color are your underpants? This is the question that must be answered! I’ll have the [tabloid scandal rag] News of the World on you . . .”

Satisfied with his repartee, Strummer then let the music talk. A twin-guitar crescendo ensued, heralding the long-delayed song, followed quickly by an equally fiery “I Fought the Law.” This one-two punch was intended to leave anyone hard-pressed to deny that a genuine Clash was in the house.

Skepticism nonetheless was easy to find—and not simply due to the absence of Jones. In truth, the four big UK music weeklies—NME, Sounds, Melody Maker, followed by Record Mirror—had for years tended to savage anything The Clash did. Sheppard laughs: “Somebody asked me once, ‘Were you hurt by the bad reviews that The Clash got in England?’ And I said, ‘Well, they haven’t had a good review since the first album—and that got panned by some people!’”

It was not surprising when the first review—by Jim Reid of Record Mirror—found lots to criticize about the Leicester show. Decrying a “stultifying lack of imagination,” Reid wrote, “The reconstituted Clash—three young blades, a Marlon Strummer, and a Mean Boy Paul—are five punky curators with a traveling ‘Museum of ’77.’ Muscular, energetic, and ultimately pointless.”

Reid wrote that the powerful show put Leicester “under punk rule” for two hours, and allowed, “The issues The Clash deal with are important,” before delivering the coup de grâce: “It’s just that the form they express them in has become meaningless . . . When Strummer screams ‘White Riot’ it doesn’t mean anything.”

Despite this, one gets the sense that—under his cynical pose—Reid liked the show, ranking new songs like “This Is England” and “Three Card Trick” alongside “the early—and best—Clash.” Conceding that “a Clash show is nothing if not spirited,” Reid concluded with a backhanded compliment: “As an exercise in nostalgia it sure dumps on the Alarm,” a punk-inspired band then making waves alongside the likes of Big Country and U2, who were also summarily dismissed.

Hardened by past criticism in the weeklies, the band shrugged it off. Vinyl later made it clear the new Clash was “wasn’t meant for them,” as the unit was not interested in the pop-novelty merry-go-round ridden by these publications. “The Kleenex scene,” scoffed Strummer. “Blow your nose on it and throw it away.”

Another skeptic was harder to dismiss. Since the Victoria Park “Rock Against Racism” show, teenage Clash fan Billy Bragg had begun to make some riots of his own. Bragg: “There was a time in 1977–1978, everyone seemed to be in a band, and every door seemed to be open to young nineteen-year-olds with attitude and short haircuts. It was like a cultural revolution. It was going to change the world—particularly, The Clash were going to change the world. I fervently believed that.”

Taking the folk troubadour stance and marrying it to an acerbic punk aesthetic, Bragg had won a growing, passionate following as a solo artist. Wielding an electric guitar, a romantic’s heart, an irreverent sense of humor, and a big mouth, Bragg laughed, “When I started out, I wanted to be a one-man Clash!”

Perhaps because of the band’s role in inspiring him as an artist and budding activist, Bragg had been bitterly disappointed with their trajectory: “It seemed that The Clash had completely lost the fucking plot with Sandinista! I didn’t really even listen to Combat Rock.” He sees this as part and parcel of a broader ennui: “By the mideighties, I’m becoming very disillusioned with all my hopes for punk in general. What’s happening is that the focus is moving toward the New Romantics. Style is starting to reassert its dead hand over content.”

Wincing at the thought, Bragg continues: “All of the things that I dressed like an idiot for seemed to be coming to nothing—we just seemed to have cleared the way for Spandau Ballet! Everything else was going more and more stylish, more and more huge productions—the idea of going the opposite direction, just one guy with turned-up jeans and white T-shirt and a beaten-up electric guitar was a classic ‘zag’ when everyone else was ‘zigging,’ you know?”

This was largely the critique that had led to the new Clash’s birth. Nonetheless, Bragg began to roast The Clash in his live performances. Bragg: “I’d been saying onstage that the new band that are out on the road—it would be simpler if they just drop the ‘L’ from the name and just called themselves ‘The Cash.’”

He later admitted—with a sad laugh—“That was a really nasty thing to say, wasn’t it?”

The irrepressible Vinyl makes short work of the slam: “Say what you will about the last version of The Clash, but it wasn’t designed in any way as a money-making maneuver. The record company would have been a lot happier with Mick still there . . . What a daft thing for Bragg to say!”

Billy Bragg and Joe Strummer, Colston Hall, Bristol, UK, February 13, 1984. (Photographer unknown.)

Daft or not, Bragg then found himself being asked to open for the same band he was publicly criticizing at Colston Hall in Bristol, the day after the Leicester show. On one hand, this made sense. Strummer had said, “I wouldn’t cross the road to buy a record,” except “maybe Billy Bragg’s one.”

The band had another agenda as well, however. Bragg—who had never met Strummer or Simonon before the show—found himself on the hot seat that night after sound check. “Joe and Paul buttonholed me about what I had been saying when we met, and I had to kind of sheepishly admit my wrongdoing.”

Yet Bragg was not really that chastened by the sit-down: “I was already a heretic, so it didn’t really matter.” But when he saw the band live that night, Bragg was transported: “I was dancing in the aisles . . . The spirit was still there, Joe still had the passion, and I thought they were great, actually. They were more musical than the old Clash, I felt—maybe the additional guitar helped.”

This was no small concession, for as Bragg freely admits, “I was such a Stalinist about The Clash. If they were shit, I would have been, you know, mortified, and sulked off somewhere. The fact that I was bopping in the aisles . . . Clearly, they were still The Clash, whatever else was going on.”

After seeing the band in action, Bragg also understood their tête-à-tête more deeply: “It seemed to be clear that Joe and Paul really wanted to make a point of proving that they still had it, which is why they were buttonholing me.”

The new Clash was ready to push the envelope. Pressed to explain what the band gained under its new two-guitar regime, Sheppard—interviewed for Radio West before his hometown debut in Bristol—didn’t hesitate: “A bit of desperation, a bit of energy—a lot of energy—and a bit of new blood. What they need.”

That no-nonsense ethic held true for other aspects of Clash affairs too. Asked if joining such a successful band meant not having to carry his own gear anymore, Sheppard responded, “I don’t like poncing around while somebody does stuff that you could quite easily do . . . What you [can] do, you do.”

But many skeptics remained as their campaign prepared for continental Europe. In the face of this, Strummer tried to encourage Sheppard and White. As road manager Ray Jordan recalls “Joe [told] them, ‘If the audiences give you any shit, just give it to them right back . . .’” While Jordan was skeptical himself of the new band, he admitted, “[Nick and Vince] put themselves on the line.”

It was not simply the guitarists. All the members of the new Clash were fighting for their lives on artistic terms—even as they were doing the same, in some sense, for everyone’s lives, endangered by the threat of imminent nuclear war.

Strummer had told Mikal Gilmore in 1982, “We ain’t dead yet, for Christ’s sake! I know nuclear doom is prophesied for the world, but I don’t think you should give up fighting until the flesh burns off your face.” By singing “Are You Ready for War?” night after night—with lines like “I ain’t gonna lay down and die / playing the global suicide”—Strummer was pressing the issue the best way he knew how.

In California, Strummer had argued rock music was the only way to reach young people. Few issues could be more critical than the nuclear arms race. As Vinyl noted later, “We supported groups like CND”—Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, touted on their 1980 “The Call Up”/“Stop the World” 45—“but at same time, they seemed very middle-class, university-intellectual types. We wanted to reach the kids they weren’t reaching.”

The single had risen to #40 in the UK, so was only marginally successful in this aim. The songs were gripping nonetheless. “Stop the World” was a raw stream-of-consciousness screed warning of atomic devastation. While “The Call Up” mostly spoke against the draft, it also evoked the Doomsday Clock created by The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists to dramatize the danger of nuclear holocaust.

When the Clash single came out just after Reagan’s election, the Clock stood at seven minutes to midnight. In January 1984, however, the hands were moved to only three minutes to midnight, the closest they had been since 1953. While the Bulletin criticized Soviet actions that increased the danger—such as the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan and deployment of SS-20 intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Eastern Europe—by 1984, it was especially alarmed by US policies.

Ronald Reagan was the Pied Piper that Strummer had warned of in Leicester. The singer was connecting the same dots as influential antinuclear activist Dr. Helen Caldicott, who called Reagan the “Pied Piper of Armageddon” for his disarming style, which made his warmongering seem friendly, even parental.

Caldicott later elaborated: “At a fundamental level people enjoy being cared for by supposedly strong leaders. This gives them the freedom to avoid the true responsibilities and autonomy of adulthood, with all its attendant details. They can then behave as adolescents needing a father or a mother figure. And Reagan fit this pattern. It was a pity that the father the American people had chosen was not a creative, vital figure, but such a destructive one.”

Caldicott spoke from direct experience, for she had met with Reagan in December 1982, thanks to the intervention of his daughter, Patti Davis. Reagan found Caldicott to be a “nice caring person . . . but she is all steamed up and knows an awful lot of things that aren’t true.” The doctor was horrified to discover the president was apparently unable to distinguish between Reader’s Digest allegations and top-secret intelligence data. Reagan’s emphasis on building more bombs as to prevent nuclear war seemed delusional to her.

“Peace through strength” was Reagan’s key talking point. He was a member of the Committee on the Present Danger (CPD), an advocacy group of powerful right-wing hawks who believed that the US had slipped dangerously behind the USSR in military power. This was not true—but once in office, Reagan acted on this belief by vastly ramping up arms spending, alarming the Soviets.

The danger was heightened by Reagan’s skepticism about arms control talks. For him, as for the CPD, such agreements were essentially meaningless. The Soviets couldn’t be trusted—the US had to be stronger than the Soviets, so its rival would not risk an attack. Ergo, Reagan and his ilk were the real peace activists, their preparations for war the most effective way to prevent it.

A novel interpretation, and perhaps it was true. Still, Reagan’s words recalled the prescient warning issued by George Orwell about “war propaganda . . . disguised as peace propaganda.”

After speaking with Reagan, Caldicott agreed. She saw the flaw in his argument: military buildup would make the Soviets fear attack from a stronger America, so they, in turn, would build more weapons. The US would do the same—and on and on, with tensions building toward a breaking point.

This unending arms spiral was insanely expensive, foreclosing more socially beneficial uses for the money. It also held other dangers, for its momentum would almost inevitably lead to war. In Caldicott’s 1984 book Missile Envy, she argued, “The logical consequence of the preparation for nuclear war is nuclear war”—a direct rebuttal to Reagan’s assertions in their meeting.

Reagan claimed to be misunderstood. Yet it is more likely that he believed—at least at the outset—that it was in America’s best interest to scare the Soviets with tough talk and military buildup.

In Reagan’s home state of California the previous month, Strummer had lambasted the leader: “His job is trying to press that button. And when he presses it, he wants 900 million missiles, not nine thousand. He wants the Fourth of July from here to Timbuktu! And he’s going to get it unless people snap out of it.”

This might seem wild overstatement—but the administration’s lavish wish list of superweapons gave ballast to Strummer’s claims. Reagan, as one wag put it, “had never met a weapons system he didn’t like.”

Perhaps the most destabilizing weapon of all would be the one Reagan touted as a bid to end the arms race: the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), announced in late March 1983, two weeks after his “evil empire” speech. Intended to intercept incoming Soviet missiles, SDI was derisively dubbed “Star Wars,” and dismissed by many experts as an insanely expensive boondoggle that could never work.

Reagan portrayed SDI as a defensive shield that could prevent a Russian first strike. To the Soviets, however, it appeared to facilitate a first strike, allowing the US to attack without fearing retaliation, thus fatally undermining the Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) doctrine at the heart of deterrence.

This was dangerously destabilizing, given that MAD had arguably prevented nuclear war for more than three decades by making it unthinkable, since both sides would be destroyed, no matter which struck first. According to analyst Marc Ambinder, “By November of 1983, Russia was convinced that US nuclear doctrine had been changed to include a tilt toward launch-on-warning or first strike posture.” This meant the margin for error was frighteningly slim.

The Washington Post later described 1983 as “the most dangerous year” of the US-Soviet face-off. Despite growing support for a nuclear freeze, the shooting down of KAL 007 on September 1 kicked off ten weeks of unprecedented peril. The overkill possessed by both sides, the fever pitch of anger and fear in the absence of ongoing dialogue, all made for an extraordinarily volatile cocktail.

Reagan and Thatcher star in a 1984 satirical movie poster. (Designer unknown.)

Civil Disobedience Is Civil Defense button, 1984. (Courtesy of Greg Carr.)

The Future in Our Hands button. (Courtesy of Mark Andersen.)

This is the context in which Stansilav Petrov made his fateful decision. Arms expert Bruce Blair asserts the US-Soviet relationship “had deteriorated to the point where the Soviet Union as a system—not just the Kremlin, not just [then–Soviet leader Yuri] Andropov, not just the KGB—but as a system, was geared to expect an attack and to retaliate very quickly. It was on hair-trigger alert. It was very nervous and prone to mistakes . . . The false alarm that happened on Petrov’s watch could not have come at a more dangerous phase in US-Soviet relations.”

The same was true of Able Archer 83, a massive NATO military exercise held near the Soviet border shortly thereafter. Thanks to a long-classified document finally released in 2015, it has come out that the president’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board had reported, “In [November] 1983 we may have inadvertently placed our relations with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger.”

While this near miss was long suspected, the document erased all doubt. According to the New York Times, “The fact that the Warsaw Pact’s military response to Able Archer was ‘unparalleled in scale,’ the board concluded, ‘strongly suggests that Soviet leaders may have been seriously concerned that the US would use the exercises as a cover for launching a real attack . . . Soviet forces were preparing to preempt or counterattack a NATO strike.’”

As the report concludes, “This situation could have been extremely dangerous if during the exercise—perhaps through a series of ill-timed coincidences or because of faulty intelligence—the Soviets had misperceived US actions as preparations for a real attack.” Such misperception was glimpsed, but then sidestepped, thanks to the cool head of Lt. General Leonard Perroots at Ramstein Air Base in West Germany, who, according to the report, made a “fortuitous, if ill-informed” call to not escalate in response to the Soviet moves.

The board’s report quotes Reagan describing the situation as “really scary” in June 1984 after he read “a rather stunning array of indicators” of Soviet war preparations compiled by the CIA in the wake of Able Archer. While Reagan felt America’s good intentions should be self-evident, the world was not so trusting.

Only one nation had ever used nuclear weapons: the United States. The Soviets knew this and, given Reagan’s words and actions, assumed the worst. The Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board warned, “It is an especially grave error to assume that since we know the US is not going to start World War III, the next leaders of the Kremlin will also believe that—and act on that belief.”

The fear was hard to avoid; even network TV paid heed. The Day After—an ABC dramatization of the aftermath of nuclear war—debuted on November 20, 1983, mere days after Able Archer had brought the world to the brink for the second time in three months. More than 100 million people watched the program during its initial broadcast, making it the highest-rated television film in history.

Rarely did a film seem so in tune with a specific moment, coming at the end of what were perhaps the most dangerous months of the Cold War. One of the film’s viewers was Ronald Reagan. Genuinely moved, he wrote in his diary that the film was “very effective and left me greatly depressed.”

Few had the chance to know as many of the specifics at the time as Reagan, but many made reasonable guesses about the gravity of the situation. Joe Strummer was a serious student of the nuclear threat and was thus reasonably terrified.

After the January 19 show in Santa Barbara, he gruffly challenged a skeptical interviewer—Record’s John Mendelsohn, a self-described “long-ago college radical”—about American complacency in the face of US-backed savagery in Central America and the nuclear arms buildup. Strummer: “Every American is responsible for what their government does—if it ain’t being done in your name, whose name is it being done in? I read all about the Committee on the Present Danger, and I know they are the ones calling the shots. Why doesn’t every American know this? Why are they all on drugs and goofing off?”

Unimpressed, Mendelsohn dubbed Strummer “the mouth that roared,” comparing him with a rabid dog running at “full froth,” and calling The Clash “the most shrilly self-righteous boors in pop history.” In retrospect, Strummer appears to have been largely correct. Reagan’s pursuit of policies promoted by the Committee on the Present Danger had brought the world into the gravest danger imaginable.

Words carried a deadly logic. If the USSR was simply an “evil empire” as Reagan said, acting outside the bounds of human decency, what option did the West have but military confrontation? Such language fed the feedback loop now spiraling the world toward nuclear holocaust.

Saner voices challenged both superpowers to stand down. In October 1983, in what UK activist E.P. Thompson called “the greatest mass movement in modern history,” nearly three million people across Western Europe protested nuclear missile deployments and demanded an end to the arms race. The largest crowd of almost one million people assembled outside the Hague in the Netherlands.

In London’s Hyde Park, 400,000 people participated in what was probably the largest demonstration in British history, opposing the arrival of US nuclear-armed cruise missiles. While Thatcher had asked Reagan to delay the deployment until after the 1983 election, they were due to arrive at the Greenham Airbase in early November, just before the Able Archer exercises began.

Despite knowing that British public opinion opposed the cruise missiles, Thatcher refused to bend. Thatcher biographer Charles Moore reports, however, that even she was worried by the escalation in rhetoric and the danger of war. This concern didn’t stop Thatcher from authorizing spying and harassment against the peace movement or suggesting that it served Soviet interests.

The new Clash ventured into this maelstrom of fear and mobilization with an eight-date tour of Europe. Vowing to “outwork those heavy metal bands” with relentless gigging, Strummer and the others wound their way through Norway, Sweden, West Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and France.

Before the tour’s second show—at Johanneshov Isstadium in Stockholm, Sweden—the unit posed backstage for a photo that captured the confrontational spirit of the moment. The Clash stood starkly outlined against a white backdrop in dark-colored quasi-commando gear. Strummer is in white, flanked by the others. With a newly trimmed Mohawk and brandishing his Mohawk Revenge shirt, the singer has a snarl on his lips and his fists balled up, as if ready for a rumble.

A casual observer could have been forgiven for wondering if the band was on a mission of mayhem rather than peacemaking. In fact, The Clash had long been ambiguous on the question of war and peace; the same Strummer who composed lines like “when violence is singing / silence the sound” and “I don’t want to kill” also wrote “I want a riot of my own” and “I don’t mind throwing a brick” and wore a Red Brigade/Red Army Faction T-shirt at the biggest UK show they ever played, the Rock Against Racism rally in Victoria Park.

Moreover, The Clash’s support for armed guerrilla movements such as the Sandinistas and El Salvador’s FMLN was well documented. As already noted, the martial-sounding “Are You Ready for War?” hardly came across as a pacifist ballad. One observer approvingly noted, “They looked and moved like a guerrilla unit onstage.” A more skeptical one groused, “For a group so against the machinations of violence they still get an awful lot of mileage from its imagery.”

The ambivalence was real. Strummer would argue, “Real revolutions are in the mind,” while in the next breath asserting, “Mind you, I think there’s really going to be an armed struggle between the have-nots and the haves of the world.”

Asked by one interviewer about the band’s “army surplus terrorist chic” clothing, Strummer responded, “It’s just self-defense.” With his questioner at a loss, he elaborated: “You take a Green Beret, who’s this well-trained killing machine, which is what we’re against. So how do we express what we’re opposite to—by dressing like some shambling hippie stoned on acid? The point is, if you’re going to defend yourself, you’ve got to be as fit and tough as the opposition.”

Before a sold-out crowd of eight thousand in Stockholm, The Clash seemed ready for the fight. After Vinyl’s rousing intro, the band kicked off with “London Calling,” “Safe European Home,” and “Are You Ready for War?” with “Know Your Rights” thrown in. The intense reaction led Strummer to briefly stop the show to urge the audience to step back, lest folks in front be crushed.

The show had some rough patches—a muffed, out-of-tune opening to “Complete Control,” a sluggish “Dictator”—but overall the band was hitting its marks. The tension of playing amid the expectations of the UK home crowd was absent, and no Jones advocates made themselves known. Strummer remained spirited, speaking with brevity and passion on topics like Central America, police brutality, and race relations. He also interjected shouts of “1984!” into “I Fought the Law” and “White Riot,” and called out Reagan by name in “Are You Ready for War?”

When the band returned for its first encore, “Glue Zombie,” Strummer provided fly for the ointment, shouting, “I’d like to say something to stop you all cheering at once—I say, from now on, drugs are crap!” If the rhythm was a bit static, the singer’s throat-shredding invested the tale with pathos, suggesting sympathy for—even identification with—the addict’s plight.

Meanwhile, Mick Jones was making himself present via the legal injunctions that—according to Clash scholar Marcus Gray—were greeting the band at every stop. The notices were ignored, and the shows went on, but it was getting harder to brush off rumors of a rival Clash, especially once concert impresario Bill Graham reported getting a call from Jones promising to bring “the real Clash” to tour Stateside.

So when The Clash returned for a second encore that night amid a sea of flickering cigarette lighters—a concert ritual Strummer found tiresome—this was on his mind: “We are about to play a song entitled ‘We Are The Clash.’ You way well have heard there might be two or three or four Clashes. I DON’T CARE. Let there be five hundred! As long as there is one real one . . . We need to hear TRUTH!”

The band then crashed into the song, which now featured a new opening verse evoking the 1982 conversations with fans in Australia and Japan. While a kinetic call-and-response revamp of the chorus tried on recent dates had been dropped, the song was a bit less stiff than the studio demo, with stirring guitar lines.

There were also less-fortunate adjustments, especially to the chorus. Before, the “We are The Clash” line had been used once, the focus being on “We can strike the match / if you spill the gasoline.” Now, “We are The Clash” was repeated three times, with the “strike/spill” couplet split apart and de-emphasized. The song’s title had been its weakest link; now it was front and center.

The song now seemed less about cocreation with the audience, and more about staking a simple claim to the name. If a brutal power still shone through, this lyrical shift confused the tune’s intent and undermined its resonance.

On this night, however, any doubts were dispelled by the set’s momentum, with blazing renditions of “Brand New Cadillac,” “Armagideon Time,” and “Janie Jones” following “We Are The Clash.” When the third and final encore of “English Civil War” and “White Riot”—introduced as an “old English folk song”—was over, there was a sense of well-earned triumph in the air.

As the crowd called out for more, an ebullient Strummer shouted a goodbye and strode off the stage. Gray panned the performance, but a Swedish newspaper’s verdict seemed closer to the mark: “Everything works for the ‘new’ Clash.”

Big crowds and rave reviews in Europe—“New Clash Is Excellent,” from a newspaper in Oslo, Norway.

Offstage matters were considerably less copacetic. “You can forget Joe, you can forget Paul, you can forget everybody,” White snapped later. “Bernie was the man with the controls. He was the one dictating. I was in a situation where I had to listen to him.” This was hardly encouraging, as Rhodes tended to be a drill sergeant at the best of times, albeit one of the Marxist variety, with perhaps hints of Asperger’s syndrome. Sheppard: “You’d come offstage feeling good, but there would be Bernie to bring you down . . . Nothing was ever good enough.”

Rhodes’s approach was intended to foster “self-criticism.” Knowing that rock nourished hedonism and ego-tripping far more readily than revolution, Strummer defended the value of the practice: “Every star surrounds himself with yes-men—we’d rather have a team with internal self-criticism.”

This reflected the influence of Chinese Communist leader Mao Tse-tung. In the 1940s, Mao had written, “Conscientious practice of self-criticism is still another hallmark distinguishing our Party . . . To check up regularly on our work and in the process develop a democratic style of work, to fear neither criticism nor self-criticism—this is the only effective way to prevent all kinds of political dust and germs from contaminating the minds of our comrades and the body of our Party.”

In principle, the practice was both common sense and revolutionary. Self-criticism was adopted by elements of the New Left in the late sixties and early seventies. Perhaps the best-known exponent was the Weather Underground, a splinter faction of Students for a Democratic Society, the most important US student organization of the 1960s. In 1969, the group—who soon made its name with a series of bombings, including of the Pentagon and US Capitol—put striking new lyrics to the holiday standard “White Christmas”: “I’m dreaming of a white riot.”

Whether Strummer or Rhodes knew of this turn of phrase is unclear, but they were aware of the group. While the courage of the Weather Underground was undeniable, its effectiveness was less certain. Self-criticism in their hands soon appeared to be less a tool of democracy than a means of control. This was not so different than in Mao’s China—or, some felt, within The Clash itself.

As Strummer touted self-criticism, he denounced groups who operated like businesses. He noted, “We did eight gigs with the Who and looked at them and thought, ‘Is that the end of the road? Four complete strangers, going on for an hour and then off?’” Strummer’s stand was clear: “I want to be friends with the members of my band . . . I want [us] to be a real team, not a stage-light team.”

Like self-criticism, this made sense in principle. However, the regular hectoring by Rhodes—in practice the main critic, and rarely of himself—undermined morale.

So did the gap between Strummer’s pronouncements and the fact that the three newer members were paid minimally—£150 a week, about $225—and often felt treated like hired help; janitors wielding a “guitar broom,” as White put it. The trio swiftly grew to dislike the band meetings in which Rhodes held forth on all manner of perceived failures and sometimes goaded others to do the same.

It was not an easy situation. The Clash was an unlikely combination of Top 10 pop stars and would-be revolutionaries. Howard, White, and Sheppard knew they could not expect to play a fully equal role in the band immediately. To suggest by word and deed that such full membership depended on working hard to earn the necessary trust hardly seemed out of bounds, and they granted as much.

Nonetheless, a practical reality was that The Clash, legally, was now a limited liability company whose members were Strummer, Simonon, and Rhodes. This reinforced a second-class status for the others that chafed against the oft-stated desires to have a fully bonded platoon and contribute to genuine equality in the world.

Nor did it make much sense to treat members of the team so harshly that at least one—Peter Howard—began to call band meetings “Bernie’s dehumanization sessions.” If onstage The Clash set such contention aside in order to try to give it all to the moment, such unnecessary abuse didn’t make matters any easier.

Given punk’s antiauthoritarian inclinations, this was also incentive for acting out, such as White’s impromptu bathroom liaison in Stockholm with Rhodes’s girlfriend. At best, this was White’s effort to strike back at Rhodes—who he had quickly grown to loathe—in the most painful way possible. At worst, it suggested that White had the impulse control of a three-year-old. Neither option was glad tidings for a band with such an ambitious agenda, in such a challenging moment.

This discord in the ranks wasn’t visible onstage. With the band playing night after night, the five began to truly gel musically. As the tour crossed Europe, The Clash continued to draw large crowds and enjoy ecstatic fan reactions.

The home front was never far from Strummer’s mind. Before a crowd of seven thousand in Düsseldorf, West Germany, he paused after “This Is England” to note acidly, “I’m warning you, very soon it’s going to be Margaret Thatcher über alles,” referring to the German national anthem that was associated with the Nazis.

Once again Strummer could be accused of hyperbole, yet some truth lurked. While all may have seemed quiet back home, it felt to some like the calm before the storm. Ever since the NUM had banned overtime, close observers were waiting for the other shoe to drop. That shoe fall would not be long in coming.

Yet while the war dance between Thatcher and the miners was worrisome, other developments were even more alarming. In Milan, Italy, Strummer dedicated the song “Jericho” to “all of you who went to Comiso and stood there in the pouring rain, to tell them we don’t play a Yankee game . . .” The Comiso military air base was the Italian equivalent of the UK’s Greenham, receiving US cruise missiles and thus becoming the venue for mass protests.

By the time Strummer spoke, the missiles had already arrived at Comiso despite the outcry, as they had at Greenham and Molesworth in the UK. Their mid-November arrival caused uproar in the British Parliament. Labour leader Neil Kinnock called it an act of “reckless cynicism . . . that makes Britain a more dangerous place today than it was yesterday.” Thatcher responded that it was “not true” that deploying cruise missiles meant escalating the nuclear arms race.

Referring in part to a recent decision by NATO ministers to rid the alliance’s stockpiles of outdated nuclear weapons, Thatcher claimed that there now were 2,400 fewer US nuclear warheads in Europe, even with the new arrivals. While technically true, this conveniently overlooked the fact that cruise missiles—small, easily movable, difficult for radar to detect as they could hug the ground, yet far more powerful than the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki—were qualitatively quite different than the decommissioned weapons.

The Soviets recognized this and, as a result, threatened to walk out of long-delayed Geneva arms control negotiations if the cruise missiles were deployed. Thatcher was losing the argument with the public, as polls showed that 59 percent of the British opposed taking cruise missiles. Nonetheless, she pushed back against the Greenham Women’s Peace Camp’s round-the-clock protest outside the base, with police regularly making arrests and evicting protesters.

* * *

As all of this was unfolding, Joe Strummer’s personal life was about to change fundamentally. Two days after the Milan show, on February 29, his father Ronald Mellor died suddenly of a heart attack during a gall bladder operation. While Mellor had dealt with heart difficulties for some time, the death was nonetheless shocking.

The news reached Strummer at the band’s final European date, a Paris show that had been rescheduled to March 1 when an earlier gig was scrubbed by a transportation strike. It would take some time for his band to find out, however, as Strummer played the show without telling the other musicians what had happened.

His father’s wake and funeral happened two days later on March 3, when The Clash was booked to play a gig at the Edinburgh Playhouse in Scotland. Strummer went to remember his dad, then got in a car and rode to the show. Most of his bandmates still didn’t know what had happened.

Strummer had become a father and lost his father in a matter of months. Sheppard: “Becoming a parent and losing a parent—these are two of the biggest life changes imaginable. Joe was dealing with them in the midst of trying to resurrect The Clash. The pressure—and grief—must have been immense.”

Vinyl agreed: “Looking back at it now—and not from my point of view at the time—[the rebuilding of The Clash] is really not happening at the right time for Joe in his personal life, he and Gaby are starting a family, his parents are not well. It happens all the time in a band, a gang, whatever . . . At some point, the other side of people’s lives is going to take over, it’s going to develop. And gang life becomes secondary, in certain aspects. Then you’re trying to juggle, you know?”

Vinyl also knew Strummer carried deep pain from his childhood and his relationship with his parents—often absent due to his father’s work overseas in the British foreign service—but not much beyond that. Vinyl: “Joe’s childhood was a real off-limits subject. Even to somebody like myself, who was fairly close to him.”

In a late-1976 interview with Caroline Coon, Strummer let down the wall a bit: “The only place I considered home was the boarding school my parents sent me to. It’s easier, isn’t it? I mean it gets kids out the way, doesn’t it?”

The bitter words masked a more complex reality. Strummer’s father lost his own parents in a car crash at an early age and grew up in an orphanage with his brother. One can only speculate how this trauma factored into the decision to place Strummer and his brother in boarding school at the ages of eight and ten. In any case, the pain appears to have been handed down to the next generation.

Strummer spat out adolescent venom to Coon: “[Boarding school] was great! You have to stand up for yourself. You get beaten up the first day you get there. I’m really glad I went because I shudder to think what would have happened if I hadn’t gone . . . I only saw my father twice a year. If I’d seen him all the time I’d probably have murdered him by now. He was very strict.”

The harsh remarks hinted at Strummer’s fraught relationship with his father and, by extension, his mother, Anna MacKenzie. While Vinyl senses that much had been left unsaid between the two Mellor men, he declines to speculate further.

Nonetheless, a man whose childhood was marked by long separations from his parents while at a stern boarding school, who lost his only brother to suicide during that time, would likely carry lasting wounds. Such a person might feel special guilt leaving his own newborn for long stretches as well—but this is exactly what would happen if The Clash were to be tireless road warriors as promised.

In a sign of how dysfunctional intraband communication could be, Sheppard, White, and Howard only learned about Strummer’s loss a week later. Sheppard: “There was a big to-do about something or other, and all of a sudden Bernie is laying into us, screaming about how we always complain. ‘Look at Joe, he’s just lost his father and you don’t see him moaning about it.’ I was just floored.”

Strummer didn’t ask for any support with what he was going through, and would have been unlikely to get it anyway. The pace of Clash life was fast, and—as in war—there was little time for comfort or condolence. Even Vinyl himself now bitterly regrets his lack of attention to his friend on this level: “There was just so much to do. We were on a mission. Much like somebody working on a sports team is not that interested in whether one of the star players is having a second child or whatever, do you know what I mean? The guy is thinking about winning the trophy, getting the form back, or whatever it might be. He’s not thinking about their private lives and their fulfillment on that level, you know?” While Vinyl hastens to add, “I’ve changed a lot since then,” at the time, Strummer carried the burden largely alone.

This meant charging into heavy fire on his own Normandy beach: London, where the band had started, and could expect to face the most skepticism. Shows in Edinburgh, Blackburn, Liverpool, and Portsmouth had gone well. Anticipation was high, and so were ticket sales: two shows at the Brixton Academy—capacity five thousand—on March 8 and 9 sold out so quickly that three additional shows were added, with postponed Irish dates in Belfast and Dublin sandwiched in between.

* * *

Yet another front was about to be opened. On March 1, as Strummer was absorbing the news about his father, the director of the South Yorkshire Coal Board announced that the Cortonwood coal mine would close in six weeks. This sudden pronouncement angered miners employed there, as the coal vein in their pit was not exhausted, and the enterprise remained profitable.

Immediately, agitation for a strike there began, and on March 5 a vote was taken to authorize work stoppage. As the Cortonwood miners went on strike, Ian MacGregor announced that more than a dozen other pits would close in 1984, for a net loss of over twenty thousand jobs. Furious, Arthur Scargill warned that this was just the beginning of a full-on assault that would close more than seventy pits, decimating the industry.

While this indeed was the plan, Thatcher’s government denied it loudly and consistently, painting Scargill as a hysteric. Nonetheless, the Cortonwood strike spread to other pits. More and more miners came out, determined to make their stand. By March 12, so many were out that Scargill declared it a national strike.

This decision was swiftly attacked as illegitimate by the Thatcher government, which pointed out that a national vote of the entire NUM membership to approve such strike action was required. In this, Thatcher hoped to split the miners and short-circuit the strike. It is possible the NUM would not have gotten the required majority in a vote, given that a significant portion of Nottinghamshire miners—whose pits were thought to be safe from closure—opposed this action.

However, other miners whose jobs were on the line resented the possibility that those whose jobs were safe might stand aside and watch their brothers go on the dole. As a Cortonwood miner said, “We won’t give them a vote on whether or not we lose our jobs.” If this was understandable, some worried it was a strategic error by the NUM. Thatcher would batter them for waging an illegitimate strike, thus justifying what would be ruthless tactics to undermine and destroy the NUM.

Far less convincing was the argument that the NUM was foolhardy to begin a strike as spring approached. MacGregor—and behind him, Thatcher—had struck the first blow. Whether shared with the public or not, there was now a death list. Once these mines were closed, they would almost certainly never reopen—so it was now or never if thousands of jobs were to be saved.

Thatcher had shrewdly chosen the optimal time for the confrontation. Given what was at stake, however, the miners could not afford to wait for a better moment, which would likely never come. The miners knew it was do-or-die. They took to the picket lines determined to save their communities and defeat Thatcher.

The Clash take a five-night stand at Brixton Academy. (Poster by Eddie King.)

“Resistance”—the band’s live fury at Brixton Academy as the miners strike begins. (Photographer unknown.)

* * *

As pickets went up in mining communities across Britain, The Clash brought their heavy artillery to the Brixton Academy. This was home, and the band was prepared to fight to retake this ground.

The NME had put the group on the cover of its February 25 issue in preparation for the homecoming. The resulting article by Richard Cook did not neglect the hard questions, but mixed witty jabs with a sense of taking the band seriously. Cook posed his essential query early in the article: “In nin’een-ady-FORE The Clash are back again. Do we want them back? Do we need them?”

This seemed the perfect setup for yet another takedown. Astonishingly enough, what emerged instead was a genuine give-and-take, where Cook allowed himself to be touched by Strummer and Simonon’s persistent passion.

Cook challenged Strummer’s bashing of Boy George and similarly androgynous UK popster Marilyn, saying, “They are doing what you say you want to do, changing people’s attitudes,” albeit in a different way. At the same time, Cook was clearly taken with Strummer’s call for punk to once again be like a blowtorch incinerating the dismal pop landscape.

Strummer was in fine fettle, ripping drugs, apathy, and right-wing politicians: “It’s all rubbish! With Reagan and Thatcher strolling away to victory . . . That’s why we are back. We’re needed!”

Simonon: “Basically [we’re] getting on with the job . . . it’s risky. But we are a band that takes risks.”

Strummer jumped back in: “I aim to outwork all those people and get rid of them. We’ll smash down the number-one groups . . . Pop will die and rebel rock will rule.”

Strummer paused, then unleashed a final salvo: “I’m saying stop the drugs. Vote. Take responsibility for being alive. I’m prepared to dive back down the pavement again—give me an old guitar and some shoes and I’ll fuck off . . . [but] The Clash has been elected to do a job and it has been neglected. I’d rather have a stab at it with a fresh team. That’s the path of honor for me.”

Cook found himself grudgingly convinced: “It’s a heroic manifesto, a tidal wave of convictions—and maybe we need a loudmouth bastard like Strummer just as much as we need a boy in braids who says be yourself . . . Their opportunity, at a time when pop is in its most lachrymose and indulgent doldrums, is to recreate their epiphany.” Although Cook felt “this is their last chance,” he also somewhat incredulously concluded: “Is 1984 the year of The Clash?”

The band was hoping to make this so. The five Brixton shows proved to be fairly epic, with packed houses every night and over-the-top response. Its weapons sharpened by six weeks of steady gigging, the new Clash knew it had to deliver, and it did. The Irish shows were similarly spirited, with massive, joyous crowds.

Nonetheless, reviews in the UK music weeklies were anything but raves. Lynden Barber of Melody Maker picked up where Record Mirror’s Reid left off, spewing negativity. Allowing that Strummer’s “heart was (and is?) in the right place,” Barber lacerated with descriptors like “pathetic” and “farce,” terming the whole affair “nothing more than a reactionary surrender to the forces of nostalgia.”

Some slams were strikingly personal: “Poor old Joe Strummer. It’s 1977 all over again up there onstage and he desperately wants us to believe in it. Moreover, he desperately wants us to believe in him because it ain’t too nice when people get cynical and think you don’t mean anything anymore, especially when you privately realize that they’ve probably got good reason.”

Not to be outdone for anti-Clash cred, NME published not one but two slams. A review of the opening-night show—Gavin Martin’s “Jail Guitar Bores”—tipped its hat ever so slightly to Richard Cook’s relatively upbeat take, then burned it all down: “This new Clash are no big departure, they are still entangled with all the old faults . . . The calisthenics, the heroic posturing, the riot scenes and war footage are all still there . . . [They are] still hung up on self-aggrandizement.”

On one hand, The Clash was “posed perfect rebels” engaged in “hollow myth-making.” On the other hand, substance was no-go as well. Strummer’s “disparate declarations on everything from the White House, to welfare, to women’s sorry lot,” only led Martin to complain that the singer “labors his points unnecessarily—a Clash audience (even though mostly white males) knows well the level of political import and intent without having it rammed down their throats.” Describing the night as “the heaviest and most orthodox rock show I’ve ever seen the Clash play,” Martin concluded: “Mostly they were terrible.”

Lola Borg’s short, savage review of the fourth Brixton show dismissed The Clash as “mucho butcho as ever” and denigrated the audience for its “total hero worship.” Spending as much time discussing the “classical Greek” interior of the Academy and Strummer’s “hideous demi-mohican” as the music, Borg found little of value. While she professed to be turned off by the band allegedly ignoring brutal bouncers, there is little indication Borg took the night seriously in any way.

While The Clash had little reason to expect kind—or even fair—treatment by these trend-obsessed rags, this gusher of venom was still a bit shocking. Such critics would hardly have convinced Strummer to rethink his agenda, however, let alone retreat. “The thing that Joe got from seeing the [Sex] Pistols was that you don’t have to go out there and say, ‘Please like us,’” Sheppard says. “You go out and say, ‘This is what we do. If you don’t like it, the door’s at the back.’”

Likely far more significant to Strummer was the review delivered in person by Johnny Green, his longtime Clash brother. Crucial to the Clash road machine for years, Green had parted ways with the band in 1979, feeling matters were becoming too businesslike. Green didn’t dismiss the possibility that The Clash could continue on in a valid way without Headon or even Jones; however, he simply wasn’t impressed with what he saw onstage in Brixton.

Green: “I thought it was very sterile, and kind of like a cardboard cutout, really—two guitarists trying to pick up Mick’s pieces. Joe seemed to be diminished. I mean, Joe put his heart and soul into it, of course, but he wasn’t bouncing off the other members of the band. They weren’t playing as a team, you know? It was Joe and—to a lesser extent—Paul, playing with three guys who looked real good, too good, you know? Almost like someone had made ’em up to be in The Clash.”

Here, Green seems to echo one insight from Borg’s slam: “Joe Strummer is clearly in charge and the band follow his orders.” This was quite a contrast to when Strummer, Jones, and Simonon had dodged and dived with one another out front, presenting a sense of equality and teamwork. Yet to say that something is different is not the same as demonstrating that it is worse. Indeed, the new Clash was slowly finding its own onstage interplay that could prove equally dynamic.

Another Green critique seems less solid. Green claims that the new Clash “had these wooden springboards that enhance the lift of the athletes put by the side of the drum riser, so the guitarists could jump in the air, like Mick used to do, you know? And I thought, ‘Bloody hell—the lengths that people go to, to reenact something that was entirely natural and spontaneous, once upon a time!’”

Asked about this, Sheppard bristles: “I respect Johnny Green enough to be surprised that he’d believe a story like that.” It does seem hard to believe, as both Sheppard and White—now that he had found his stage legs—exhibited unaided athleticism night after night while playing the songs.

Green also seemed to share a Jones complaint: “How can [the new guitarists] play those songs with conviction? They haven’t lived them.” Sheppard’s terse response: “I played those songs with the conviction that I had for them. And I did love those songs. I made no bones about it, I was a big fan of The Clash. There wasn’t a song that I didn’t want to play, you know?” Left unsaid was that, by the end of his tenure, Jones didn’t wish to play quite a number of Clash songs.

In any case, Green found his way backstage, dodging a disapproving Rhodes and running into Strummer in a hallway. As recounted by Chris Salewicz in his epic Strummer bio, Redemption Song, “Having rid himself of his heroin demons, Johnny had put on a large amount of weight; he hardly fit into the only suit he had to wear. ‘That’s a terrible suit,’ Joe told him. ‘It’s not as bad as your group,’ replied the Clash’s plainspoken former road manager.”

Salewicz explains, “In the forthrightness of the Clash posse, an extension of punk’s professed honesty, there was sometimes an element of ‘dare,’ incorporating a subtle mind game. But Johnny’s remark cut Joe to the quick. In front of him, in the backstage corridor, Joe burst into tears.”

Green recalled, “I said to Joe, ‘What are you doing this for, for fuck’s sake?’ He burst into tears, and he said, ‘I don’t know what else to do.’ Bernard came by, and said, ‘Don’t talk to him, Joe, he’s yesterday.’ [Joe] said, ‘Fuck off, Bernard, or I’ll smack you. You don’t understand friendship, you don’t understand loyalty.’” Green soon hustled off, leaving Rhodes in command, but his words still resonated.

Strummer’s tears were no doubt real—but what did they mean? It could have just been the sign of a man under immense pressure, bone tired. Maybe he was grieving in ways too deep to express, at least for a man raised in stiff-upper-lip England, internalizing the destructive demands of masculinity. Perhaps it meant Strummer feared that what Green said was true, that the new band was not up for the mission, and that he had betrayed a friend to pursue a fool’s errand. Maybe it just meant that Strummer was insecure, even becoming unmoored amid irreconcilable demands . . . or some combination of all of these.

Despite the apparent wrestling with profound self-doubt, it is hard to find fault with Strummer’s performances at Brixton Academy, or of the band as a whole. If the heavier sound was not for everyone, it was nonetheless powerfully realized. As another longtime ally Julian Balme recalls, “They were fantastic, really, really good . . . All the new songs live sounded brilliant. With two guitarists and Joe, it was like, WOAH! They weren’t pussyfooting around. It wasn’t apologetic; it was turn it up to eleven and right in your face! There was nothing lacking in the live performances at all.”

Nor should there have been any doubt about the band’s continued relevance, the sniping notwithstanding. Beyond the trenchant outcry of numerous new tunes, several of the older songs seemed so on target they might well have been composed for precisely this moment. Arguably the most powerful was “English Civil War.” While written amid the neo-Nazi scare that Rock Against Racism helped turn back, it also fit the drama unfolding in 1984 like a glove.

Strummer knew this. In the final encore of the last Brixton show, he chose to dedicate the song to “the cold coal miner out on the picket lines, freezing his bollocks off.” The statement suggested he saw the strike not simply as a fight between the Tories and the miners, but a struggle for the soul of the country. If Thatcher was to be stopped, it had to happen now; it had to happen here.

At Colston Hall, Strummer had paused to query the crowd before igniting a crushing version of “Clampdown,” another song seemingly tailor-made for this urgent moment: “Does Britain exist? Is Britain a dream or a nightmare?”

As Thatcher’s clampdown began to descend on William Blake’s “green and pleasant land,” this was an unavoidable question.

The fight would require much, and victory was not guaranteed. It was unclear how great of an impact a band could possibly have. As the miners stood on picket lines, The Clash was about to take its own war across the ocean for an extended US tour. They would do so carrying news from the UK, while wrestling with peculiarly American challenges as Reagan revved up his 1984 reelection campaign.

So much was now at stake: for the band certainly, but much more for millions of human beings. The battle was on, and the world seemed about to turn—but in what direction? It was time to find out.