chapter four

turning the world

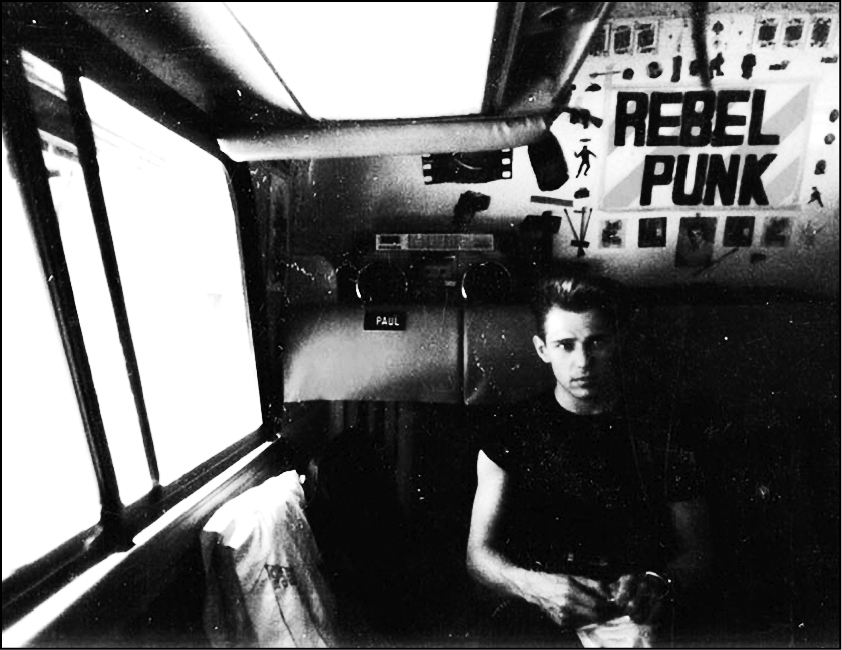

Strummer perched on TV monitors during US tour. (Photo by Bob Gruen.)

Ever since the Founding Fathers of our nation dreamed this dream, America has been something of a schizophrenic personality, tragically divided against herself. On one hand we have professed the great principles of democracy. On the other we have practiced the very antithesis of those principles.

—Martin Luther King Jr., 1964

Live your beliefs and you can turn the world around.

—Henry David Thoreau

The crowd’s applause was deafening, exhilarating. Already drenched in sweat only two songs into the night, Joe Strummer stepped to the microphone. Smiling, clearly lifted by the power of the people in the room, he shouted one word: “Lights!”

Instantly, the glow radiating from the stage was swallowed up as powerful house lights revealed a packed audience of nearly four thousand at the Sunrise Musical Theater near Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The division between performer and audience dissolved and all stood joined together by the wash of incandescent lighting.

As the other members of The Clash prepared their next salvo, Strummer spoke: “I’d like to welcome you here tonight. I’d personally like to thank each and every one of you for showing up, proving that maybe the world can be turned!”

The crowd roared again. After introducing the rest of the band, the ebullient singer quipped: “And, last but not least, my name is Ratso Rizzo!” As this reference to Midnight Cowboy’s doomed antihero seemed to fly over the heads of most of the audience, Strummer gathered himself and chanted a simple mantra: “Take drugs—don’t vote—get ready—for war!”

Knowing this as the count-off to the next song, the band returned to the fray.

This was only the third date on a two-month tour, but the new Clash was already hitting its stride. The opening “London Calling” and “Safe European Home” had always been performed fervently, but now they came across with a sort of swing, the clear sign of a band coming into its own.

Strummer’s curt intro to an equally kinetic “Are You Ready for War?” had outlined the tour’s message—and it was hardly a happy vision. Yet his hopeful energy also resonated, suggesting a rallying cry behind the critique.

The Clash had left behind a homeland just entering into what would prove to be its biggest conflict since World War II. The huge country they were about to traverse over the next months was itself at a crucial crossroads.

Reagan had defeated incumbent Jimmy Carter four years before. Now, as the world teetered on the edge of a catastrophic war, poverty in the US was on the rise, racial tension simmered, and desperation festered where once a mighty industrial economy had thrived. As a result, millions loathed Reagan.

Yet many—even some of those displaced by the economic tides—found pride, even hope, in the unapologetic vision of national renewal put forward by this conservative revolutionary. The question once asked by Reagan hung in the air: Are you better off than you were four years ago? A bitterly divided American public would render its verdict in a little over seven months.

Beyond the politics, America held a special fascination for Strummer and the rest of The Clash culturally. “I’m So Bored with the USA” notwithstanding, it was—as Vince White noted—“the home of country music and rock and roll!” So much of Strummer’s own inspiration came from there, from Woody Guthrie, the blues, the MC5, even political figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., whose speeches the singer would sometimes listen to in order to get psyched up to perform.

As such, Strummer brought a conflicted passion to the band’s US tours. “We appreciate lunatics and individuals and madmen,” he told an interviewer after the new Clash’s first show in California. “America had millions of them. All the lunatics and madmen in the entire world came to America at one time!”

But if this once-upon-a-time USA had been an inspiration, the present was less uplifting. Strummer: “So why have these corporations got in their little boardrooms, and made all these rules and anybody who breaks these rules gets fired? And nobody wants to get fired . . . Where has the pioneering spirit gone?”

America remained more than cookie-cutter corporate consumerism to Strummer. Onstage at the historic Township Auditorium in Columbia, South Carolina, five days after their blistering Fort Lauderdale show, he paused to pay tribute to “James Brown, Otis Redding, and all the greats” who had performed there.

While some called the band hypocritical for dismissing the US while so obviously besotted with it, this was not entirely fair. As Strummer would note later, there were at least two Americas: King and Reagan, the dream and the nightmare, freedom and control, pioneering innovators and corporate conformists.

Ironically, in a way, the musicians were themselves employees of a huge American corporation. Part of their spark came from that dynamic tension, a rub of ideal vs. real, as they walked the fine line separating them from their own critique of corporate power. The Clash waged war from that ambiguous space.

There was also a commercial angle. The band was venturing back into the vast American market—the biggest in the world, one that made and broke bands.

Two short years ago The Clash had gone from successful cult band to one of the biggest draws in the world on the Combat Rock tour—a jaunt that almost didn’t happen due to the internal crisis with Headon. Success had nearly swallowed the group; it had also provided muscle to push back against their overlords.

This tour itself might be seen as an example. The Clash had returned, trawling across this vast country—but in blatant violation of basic rock business mores, and much to the dismay of their label, they had no new record to flog. Asked about this, Strummer responded, “We’re just going out and playing for the hell of it. We all have a common goal now: we want to become a real band.”

Strummer also felt the moment required The Clash, not as some abstract idea, but as a signal to rally the troops before it was too late. It was no accident that the frontman introduced himself as “Paul Revere” at one of the US dates. “We’ve been elected to do a job here,” Strummer insisted. “It takes commitment.”

Yet the band was not surrendering its pop ambitions. As Strummer had told Richard Cook, “We want to take rebel rock to Number One!” This was less for the money than for the impact. Calling US underground punk heroes Bad Brains and Black Flag “closet cases” because they were on independent labels and thus might not get heard by most, Strummer wanted to get his message out to all.

Likewise, Vinyl saw no point in aiming too low. Combat Rock “was just a foot in the door,” the rooster-haired rabble-rouser declared to one interviewer. “What’s the point of getting enthusiastic about selling a million when Michael Jackson’s sold thirty million, and is probably selling another million while we talk?”

How this was going to work was unclear, and Cook had understandably been left a bit stumped. America had never embraced punk as the UK had done—and even in Britain, it was now often seen as yesterday’s news. The only punk-related acts that had made it big in the US—Blondie, the Police, even The Clash—had done so with songs that were hardly incendiary “rebel rock.”

While “Rock the Casbah” was far more substantive than any of these, its serious message was masked by its novelty appeal. This was intentional, for Strummer had often decried “preachy” performers, even noting, “I put some jokes in [“Are You Ready for War?”] so it wouldn’t be too depressing!” Flashes of humor added balance and accessibility to hyperserious themes.

However, none of the band’s relentless new material fit the “Casbah” mold, much less that of the poppy love songs “Train in Vain” or “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” This tour was a leap of faith, continuing the job that The Clash had set out to do. With forty-plus dates packed between March and May, it was also hard work.

In part, the aim was to build solidarity within the new lineup. The Clash had begun its tour in the South, slowly working down and up the Atlantic seaboard in a no-frills bus. As White recalls, “The whole tour was by Greyhound bus. No flying was allowed. It was structured this way so that we had a down-to-earth real traveling experience. We weren’t allowed to be pampered rock stars.”

Strummer celebrated the road warrior vibe: “We got a Greyhound bus, without a bunk, without a TV, without a bar . . . We just sit on the bus, we drive fourteen hours straight. We fucking road hog it!” Not everyone was so enthused. “I hated being on that hellish tin can,” Howard says.

For most, however, there was a “we’re all in it together” spirit as the tour set off. Eddie King—who was doing video for the band—recalled a determined vibe on the bus: “We were listening to a lot of Bo Diddley, the first Run-DMC album, and a song that used the Malcolm X ‘No Sell Out’ speech in a loop. That was on the tape deck all the time, it became a kind of theme: No Sell Out.”

“Rebel punk” Paul Simonon on US tour bus. (Photographer unknown.)

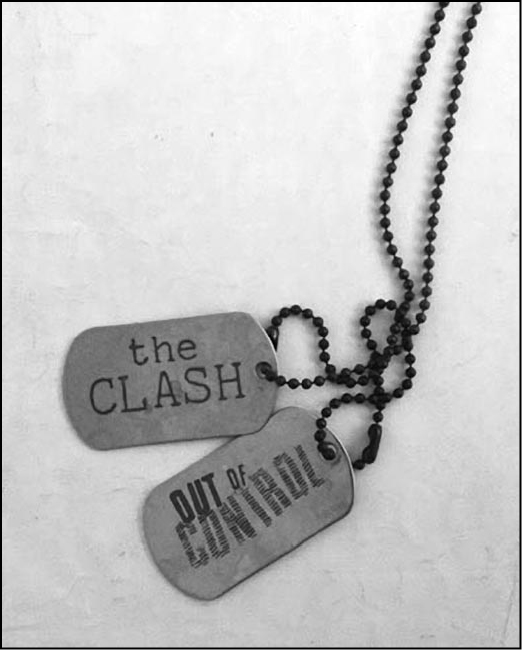

Prototype for Clash dog tags, never produced. (Designed by Eddie King.)

The spartan approach had an aim—to share hardship and build cohesion, as in an actual military unit. The entire band now wore dog tags, items originally used to identify dead or wounded soldiers. As Sheppard explains, “The dog tags were given to us by some fans that had painted them up before [the three new members] joined . . . beautifully done, with enamel paint. It was all part of the whole Combat Rock image, and the gear that we were wearing.”

Strummer told one journalist: “In my mind, I liken us to a new platoon and we’re going to go out and crawl right in front of enemy lines, get fired upon, and then look at each other to see how we’re bearing up. Can I rely on this guy when my gun jams? We’re under fire and we’re sharing that experience.”

If the metaphor was presumptuous, it signaled the band’s serious intent and special challenges. This Clash was a new entity, thrust almost immediately into an extremely demanding position by the band’s popularity. To succeed required intangible but very real glue, what analyst Jennifer Senior has called the “psychologically invaluable sense of community and interdependence” that comes “only during moments of great adversity [where] we come together.”

For Senior, the experience of combat illustrated this: “War, for all of its brutality and ugliness, satisfies some of our deepest evolutionary yearnings for connectedness. Platoons are like tribes, [giving] soldiers a chance to show their valor and loyalty, to work cooperatively, to demonstrate utter selflessness.”

Given this, she argues, “Is it any wonder that so many soldiers say they miss the action when they come home?” But if the theory behind Strummer’s “platoon” analogy was sound, it remained to be seen how it would work.

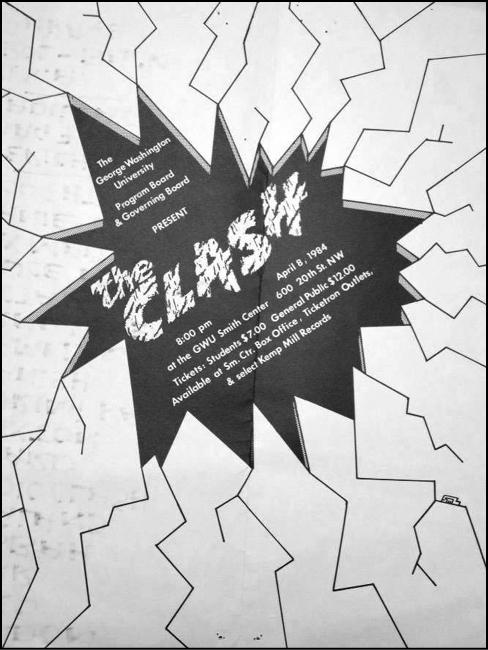

Given the fan base built over the long Combat Rock tours, expectations were high. The reengineered Clash aimed to exceed them. While Gavin Martin had scorched the band for its “massed light banks, three-prong guitar chunder and video screen backdrop,” Washington Post rock critic Mark Jenkins had a different take after seeing them in front of a sold-out crowd of five thousand at George Washington University’s Smith Center on April 8.

Jenkins was often hard to please, and had been left dissatisfied by the band’s two previous DC shows: “When I first saw The Clash, they were trying that amazing everything-coming-together-on-the-edge-of-falling-apart sound they had pulled off on their first album—but it didn’t work very well live. They’d be racing around onstage and you’d suddenly think, ‘Where’d the song go?’ It was very entertaining to watch but the music didn’t really come across.”

Jenkins was impressed by the new lineup’s energy and its music: “It was ‘the Joe Strummer show’ for sure, but with two guitar players, he didn’t have to worry about doing anything but calling everyone to war or whatever. The band had their commando ‘state of attack’ theatrics but the musical presentation was far better than the Jones-era Clash, and the new songs fit nicely with the older ones.”

Jenkins sensed an outfit with a future: “The Clash had been a bit like a club band that hadn’t figured out how to play to arena crowds. This was the first time they seemed able to project in the necessary way to be convincing at this level.”

Although two guitars seemed like overkill to some, they did bolster the Clash attack, making the sound savage and direct. Sheppard: “We were playing two Les Pauls, very loud, very punk, you know, very rock and roll—a bit too rock and roll for some people.” The twin guitars not only generated extraordinary sound and fury, but also—as Jenkins witnessed—reproduced the full power of the songs’ original arrangements which had sometimes suffered amid Strummer’s stop-and-start playing and Jones’s overly busy, effects-laden approach.

Strummer’s set list from Smith Center show, Washington, DC, April 8, 1984.

Flyer for the show.

Not all observers were as taken with the new Clash—understandably enough, given how central Jones had been. White had his own criticism of Strummer and a white suit that he sometimes wore onstage. While the Mohark Revenge T-shirt remained, the bulky suit coat suggested a Mohawked lounge singer. The guitarist derided Strummer’s “deep-orange hair and white suit under the spotlight, cabaret entertaining in an Out of Control shirt . . . the solo star. He’d become a bit of a caricature of something.”

To Howard, the singer’s sartorial displays suggested “a banana republic dictator” or “Captain Scarlet meets something out of [the Woody Allen film] Bananas.” The drummer laughs: “Sometimes, honestly, he would walk in the room and me, Nick, and Vince would look at each other: What the hell is he wearing today?”

Strummer offered few apologies. “We need an image,” he insisted. “I’m out there fighting like tigers against all these slinky, funky, junkie mothers. I’m out there in a three-ring circus, I need an image to grab some attention.” He had a point, and White—in the band, but often its biggest critic—allowed, “Despite everything, the shows continued to be good. There was something there. I felt it.”

The band also exercised artistic self-criticism, adjusting both the set lists and the song arrangements. There still was no sign of “Should I Stay or Should I Go,” and “We Are The Clash” and “Glue Zombie” had also disappeared.

While White missed “Zombie,” he was not worried about the absence of the former song. The musician didn’t embrace the song’s punk-socialist message, but his main critique was artistic: “The song just felt lumpen, with a nursery rhyme sing-along chorus . . . I felt stupid singing it.” Echoing this, Sheppard notes, “We tried different approaches with the song, but it had never really come together.”

As the band sought a creative chemistry, the sense of mission remained central, proving infectious. White: “The general consensus seemed to be that the new band had reignited. [This] return to the basic primal sound of The Clash [had] energy and conviction where two years ago there had been boredom.”

Skepticism still remained, especially among more mainstream outlets, which seemed less willing to let the departed Jones go easily. For Boston After Dark’s Doug Simmons, songs like “Sex Mad War”—one of three new ones aired at the Worcester Centrum—struck him as a paler echo of The Clash’s original intensity. He questioned how this revamped band could breach the pop mainstream without sound musical reinforcement: “Without fresh tunes, and for that matter, fresh lyrics, Strummer’s radical message is not going to sink in.”

The negative write-ups often struck Sheppard as reflecting an old-fashioned generation gap: “The decision had been made to go out and be a punk rock band. It doesn’t surprise me that [mainstream] reviewers would find [the new approach] a bit much. Presumably, they’d be older, not able to keep up with it.”

There may have been some truth here, for college papers tended to be more sympathetic to the ferocious new Clash. “Clash Is a Smash,” the Hofstra University Chronicle proclaimed. The reviewer wrote: “Guitarists Nick Sheppard and Vince White and drummer Pete Howard proved the band’s regrouping successful. They performed the . . . songs with excellent showmanship and musicianship.”

Concert review in Hofstra University’s Chronicle, April 1984.

Reviewing the Colgate University gig, Robert Capiello agreed: “Any pretensions of funk, reggae, or pop [are gone, replaced by] power strumming.” Though he wondered how The Clash might convert listeners chiefly concerned with “obtaining a comfortable corporate position and a large record collection,” to him, the band seemed up for the task: “If their new music, particularly a song called ‘This Is England,’ is any indication, a new album will be worth hearing.”

Other observers—especially European ones—criticized The Clash for a US-centric approach, assuming a monetary motivation. This was not entirely wrong. The band had to pay its bills, and the income from tickets and merchandise sales was considerable. While the absence of a new record was felt, the shows generally sold out, mostly in college venues ranging from three thousand to ten thousand in capacity.

Strummer often exhibited a disarming self-deprecation, telling a North Carolina audience, for example, “You’ve probably come to realize you’re not watching a slick operation, selling hot dogs and T-shirts as they go, spreading boredom in their wake! No, indeed, it is real human beings fucking up before your very eyes!”

The singer also offered more lofty aims, however. Challenged by one skeptical interviewer, Strummer sounded a messianic note, evoking Christ’s journeys amid prostitutes and other “disreputables.” Such urgency might seem pretentious; it was also real. The US was not only the world’s biggest music market—it also held the earth’s fate in its hands. What happened here inevitably affected the entire world—and here The Clash must thus take its campaign.

This seemed especially true as the US election drew nearer. Having rebounded from their 1982 doldrums, Reagan and his campaign coterie were sharpening their rhetorical knives for the race. At the same time, the Democrats were in the midst of the contentious process of picking their standard bearer.

Edward Kennedy, the great liberal hope, had declined to run. In his absence, the front-runner was Walter Mondale, a Minnesota Democrat who had been Carter’s vice president. If hardly charismatic, Mondale was a centrist Democrat with a reputation for integrity. A large pack of other candidates had been winnowed down on March 13—dubbed “Super Tuesday” for its concentration of primary contests—leaving Mondale neck-and-neck with a new contender, Gary Hart of Colorado.

Youthful and relatively unknown, Hart styled himself a “New Ideas” candidate, railing against Mondale as a continuation of “failed policies” that had brought Reagan to power. This tact foreshadowed the “Third Way” movement that would bear mostly sour fruit in both the UK and US in the 1990s.

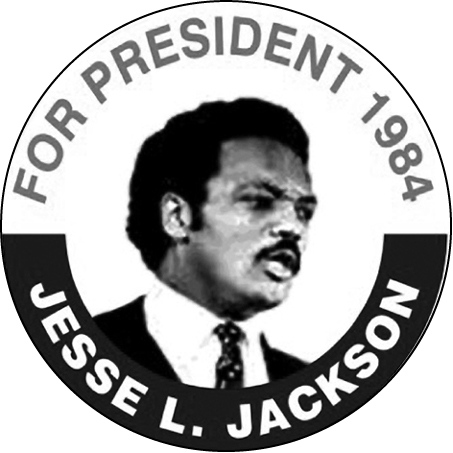

On March 17, however, a “dark horse” scored an upset victory in the South Carolina primary. African American minister Jesse Jackson electrified audiences with powerful oratory, resurrecting the hopeful energy of the civil rights and antiwar movements. A former lieutenant to Martin Luther King Jr., Jackson saw himself as the candidate of a “Rainbow Coalition,” a grassroots movement aiming to mobilize an increasingly diverse America to defeat Reagan, remake the Democratic Party, and realize an unfinished American revolution.

Jesse Jackson 1984 campaign button.

Not surprisingly, Jackson found favor with Strummer, and the Clash singer endorsed him in interviews as the “only real opposite to Reagan.” Yet Jackson was a long shot at best, and hurt his cause with anti-Semitic remarks to a Washington Post reporter. Nonetheless, Jackson’s presence helped push an inclusive and progressive agenda, suggesting the kind of vision that might be needed to challenge the Republican president’s crowd-pleasing narrative.

Strummer saw Reagan as less a rousing leader than an undeserving recipient of an accidental gift, tracing his 1980 victory to a sad legacy of the 1960s: “Ronald Reagan is the product of the drug culture. The two are synonymous in my mind. Reagan is there because we didn’t care. We kept goofing up, we copped out, and we let Reagan in. Same with Thatcher in England.”

This argument illuminated Strummer’s words onstage in Florida, making explicit his connection between drug taking and a warmonger in charge of the world’s deadliest arsenal. While this remained arguable, it is true that the sixties countercultural politics—which included a celebration of drugs as liberation—fed a backlash that helped bring elements of the working class to support Reagan.

These so-called Reagan Democrats had voted against their party—and their own economic self-interest—amid post–Vietnam/Watergate ennui, the humiliation of the Iranian hostage crisis, and the sting of “stagflation,” a deadly combo of increasing prices and lagging growth. Reagan’s promise to “make America great again” had convinced enough such voters to send him to the White House.

Would they do so again? Did 1980 herald a historic realignment of the US electorate like FDR’s 1932 election, or was it an aberration? No one yet knew.

Strummer was aware of how Thatcher’s breakthrough victory in 1983 presaged the life-or-death miners’ strike now nearing its third hard-fought week back home. However, under the cloud of possible nuclear war, he saw the stakes as even higher in the US election: “Maybe we have to be burned to learn. Hopefully people will be less apathetic about it now, or nothing will be left.”

While Strummer had no vote in this coming election, he was determined to put his thumb on the scale as much as possible. Over the past months, the singer had often urged his listeners to engage in the electoral process. He had told an Italian crowd, “Please, I ask you to use your vote—use your vote before we die!” Similar statements peppered surprised crowds on this trek across America.

Such public service announcements might seem odd coming from a band that celebrated a “White Riot” and the “Guns of Brixton.” For many on the revolutionary left, voting was often seen as a feeble, even counterproductive endeavor. It also could seem uncool for a radical rock band: “If voting could change things / they’d make it illegal,” sang the Lords of the New Church. “Whoever you vote for, government wins,” warned Crass.

Strummer was aware of the limitations of the ballot box. His new song “The Dictator” lampooned what historian Peter Kuznick termed “death squad democracy” underwritten by the US: “Yes I am the dictator / my name is on your ballot sheet / But until my box has your cross / you know this form is incomplete.”

Strummer was referring in particular to El Salvador. To justify the military aid being sent to turn back a growing guerrilla movement, Reagan had called for elections to shore up his allies. Human rights groups like Americas Watch questioned the validity of voting amid the horrific ongoing violence, the vast majority of it committed by the US-backed government forces.

Reagan nonetheless pushed forward, and the vote duly endorsed the preferred party, enabling military aid to continue. The election, however, was widely criticized. On March 7, 1984, the Christian Science Monitor reported, “Two days before balloting, the [Salvadoran] Electoral Commission estimated 720,000 people would vote. But the official count was 1,551,680—out of a voting population estimated by the US State Department at 1.5 million.”

Reagan shrugged off such inconvenient reports. The pretense of democracy had been preserved, even as death squads roamed freely. This was not surprising, as the US had a long and sordid history in the region. As Martin Luther King Jr. had warned, America had something of a schizophrenic personality: “On one hand we have professed the great principles of democracy. On the other we have practiced the very antithesis of those principles.”

Like King, Strummer was outraged by the hypocrisy, saying, “The Clash believe in freedom—even in Central America,” and noting, “American taxes are supporting quite a few [dictators] right around the world at the moment.”

The singer was scarcely less acidic about his own country’s foreign policy. Describing the UK as “the little island that once crushed the world in its fascist grip,” Strummer explained his anti-imperialist stance: “How do you think I come to write these songs? We [British] are the fucking experts.”

The US and the UK were hardly alone in organizing sham elections or supporting oppressive regimes. Such “realpolitik” was distressingly common, and the Soviet Bloc had regularly rigged polls as a way to justify faux “people’s” governments.

Why then would an aspiring revolutionary like Strummer suggest voting as a way to dislodge Reagan or any other malefactor? Simple political realism, grounded in a sense of the utter urgency of the moment.

The calculation was simple, but compelling. Absent a mass movement like that of the 1960s, the only way to stop Reagan was at the polls. Just as the miners’ victory was essential, so was denying Reagan more time in office to complete his conservative counterrevolution.

Screaming “Revolution now!” was a self-indulgence that the world could not afford, not in this moment of nuclear danger. So, night after night, Strummer would temper his rabble-rousing to advocate the mundane act of voting as an essential way to prevent war and turn the conservative tide.

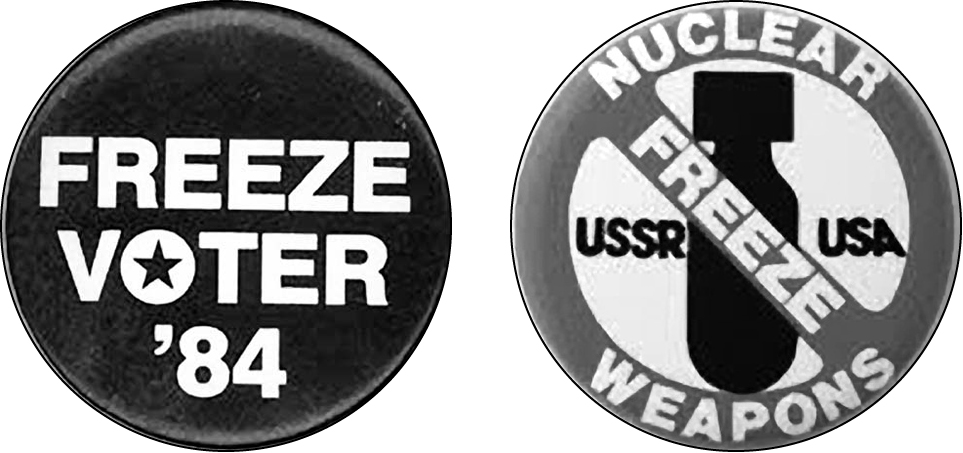

In this, the band was also acknowledging a hopeful development. Even as the band had been preparing for the US tour, Reagan’s Undersecretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger wrote an internal memo about “an important problem we face with our European allies,” warning, “The steady decline of public confidence in US policies is a real concern and one we must all work to correct.”

Nor was it just a European “problem.” Arms Control and Disarmament Agency director Eugene Rostow—a hawk, notwithstanding his title—worried that “there is participation [in the freeze movement] on an increasing scale of three groups whose potential impact should be cause for concern. They are the churches, the ‘loyal opposition,’ and, perhaps most important, the unpoliticized public.”

Nuclear Weapons Freeze buttons. (Courtesy of Mark Andersen.)

The power of the grassroots peace movement was becoming worrisome to Reagan as it spread from the fringes into mainstream America. White House communications director David Gergen later noted, “There was a widespread view in the administration that the nuclear freeze was a dagger pointed at the heart of the administration’s defense program.”

But if the band could sense this shift in popular opinion, and sought to boost it rhetorically, it did not take the next step: inviting voter registration tables to their shows. Only moral support was being given, divorced from practical politics, despite the stakes of the presidential campaign.

The impending election and possible nuclear cataclysm were not the only issues on Strummer’s mind. In Fort Lauderdale, the singer had introduced “This Is England” by saying, “We like to provide you with some information, we like to bring you the news straight from England . . . Here it is, England 1984, underneath the worst government we’ve had in living memory!”

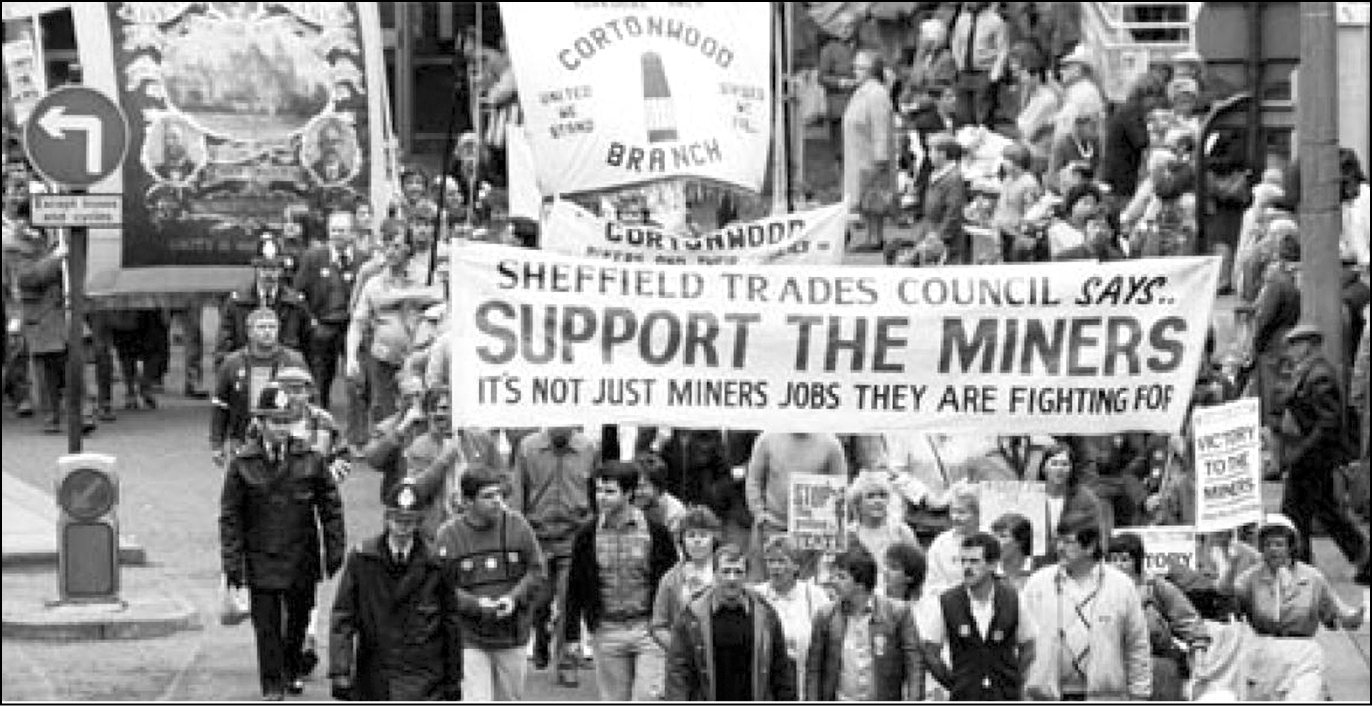

While Strummer had a broad range of complaints about Thatcher, the strike now stood at the forefront. Simon Parkes, owner of the Brixton Academy, recalls, “At first things went well for the miners. Much of the country rallied behind them, responding to the message of livelihoods lost and communities destroyed.” But, he continued, “Thatcher’s Conservatives had prepared for this battle. They were not going to fold in the face of industrial action as previous governments had.”

Sheffield and Cortonwood delegations at “Support the Miners” march, 1984. (Photographer unknown.)

A divide in the NUM helped them. While the vast majority of miners were on strike—160,000 strong—most in Nottinghamshire refused to join. The constant official drumbeat against “mob rule” and “violent” picketing encouraged this. Local courts, in turn, limited free speech, even banning picketers from decrying their errant workmates as “scabs,” leading to numerous arrests on dubious grounds.

The mines in the Nottingham region were relatively new and profitable, thus safe from closure. Why then, some asked, should we risk our jobs for the others? In addition, a national strike vote still had not been called. This crack in the miners’ solidarity was a godsend to Thatcher, one upon which she would capitalize.

This was not the main topic of conversation on the Clash tour bus, however. “Being on tour,” Sheppard says, “is like being in your own little world . . . It’s hard to pay attention to anything else.” King agrees: “England was not on my mind much, I remember feeling really cut off. Once you hit the road and start moving, you just get swallowed up, consumed by it all.”

Nonetheless, events in the UK weighed heavily on Strummer. Almost every night, he would preface “This Is England,” “Three Card Trick,” or “In the Pouring Rain” with an explicit nod to the drama. In Atlanta, Strummer took it further, coupling “Rain” with “an old English folk song”—1977’s “Career Opportunities.” This description not only underlined the continued relevance of the Clash catalog, but suggested how it connected to a centuries-long struggle for economic justice.

Although Strummer was generally skilled at balancing the “edutainment” equation, not everyone in The Clash was happy. White recalls, “Joe was pushing the political thing really hard,” adding, “I didn’t give a shit, I just wanted to play music.” If this suggested growing alienation from the band’s agenda, it also carried truth. Like any band, the new unit would rise or fall on its musical power.

For Strummer, it was a delicate balance: “We’re not being really preachy. First I want to rock and roll, to hell with the lyrics! But if the words come in handy, if they are topical, if they mean something to real life, that’s extra.” At a Worcester show, Strummer lambasted the likes of Culture Club and Wham!, shouting, “Music can do something more than put a poster on a thirteen-year-old girl’s bedroom wall!”

But what was that “something”? As The Clash took on a journey that sought—in Strummer’s mind—to help “turn the world,” it seemed likely that music’s power would prove insufficient to the task.

Such ambition was not new, however. It had helped win The Clash its famously fervent following. A Clash not straining toward “death or glory” wouldn’t be the genuine article. But a stretch of such magnitude was likely to fall short. It also might come at some real human cost.

For now, there were more mundane challenges—getting to the next show on time or keeping bandmates on good terms. Shadowing them all was a simple fact: The Clash soon needed to make a new record—a great one. As Cook had pointed out in NME, only this could solidify, define, and justify the new Clash: “They have to wipe the slate of years of their own torpor. They have to make astounding rock and roll records, iron-hard music.”

This was exactly what Strummer had in mind. Taking his moody guitarist aside, Strummer told White the US tour’s deeper purpose: to help finance the recording of a new album, while building the unit’s cohesion and shaping the songs. “We’ve gotta get into the studio as soon as possible and bang it out raw,” Strummer explained. “I don’t want to make the same mistakes we made in the past.”

Once again, the skeptical White was swept up in the force field of Strummer’s passion, envisioning a “brilliant, raw, exciting album like the first.” Despite legal challenges presented by Jones’s blizzard of injunctions, this was the goal toward which all the exertion was aimed. “We’re gonna get this album out by the end of the year,” Strummer told White. “We’ve got to.”

Strummer would relate the same ambition to whoever would listen. All the struggle and stress of the road, the building of this new platoon under fire was “what is going to make our [new] record great!” Strummer told Creem’s Bill Holdship after the Detroit show.

Holdship was a hard sell, as was his publication. For those in the know, Creem was “America’s only rock roll magazine.” It had been home to trailblazing critics like Lester Bangs and Dave Marsh. In a 1971 issue, Marsh coined a new phrase to describe a raw garage-band sound: punk rock.

As rock aficionados, The Clash loved Creem, but they had a stormy relationship with it. Holdship was also skeptical of them. Once “an idealistic college kid who believed rock and roll could ‘save’ the world,” now he had adopted the “meet the new boss / same as the old boss” credo of the Who’s “Won’t be Fooled Again.”

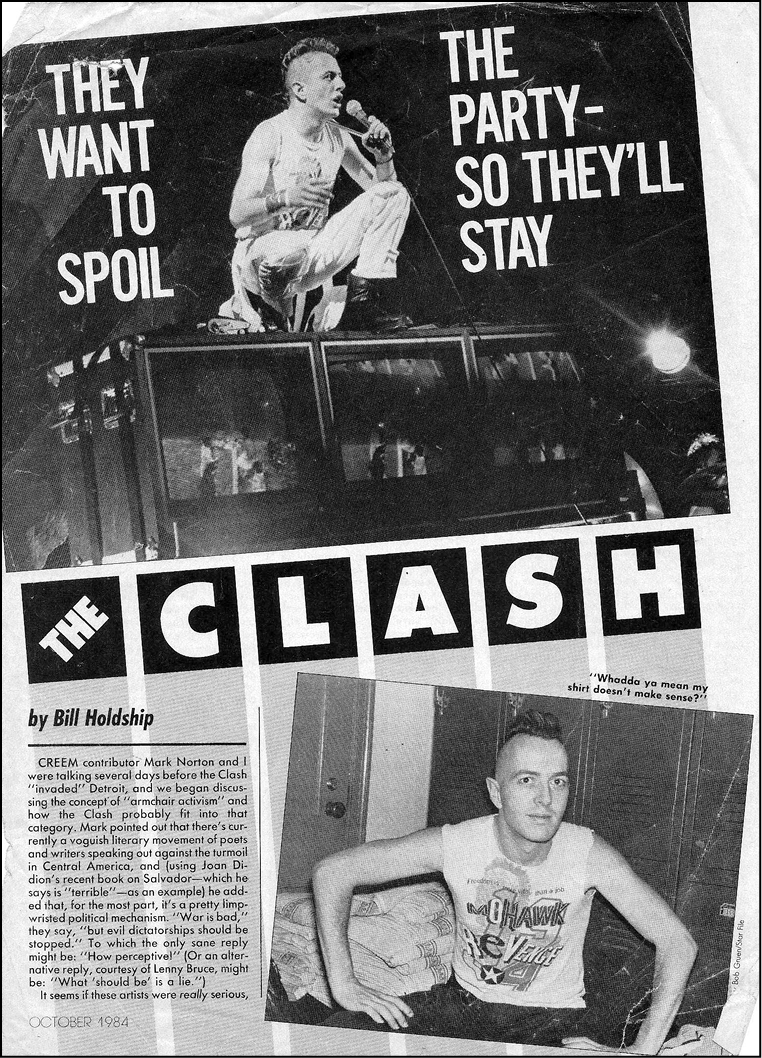

Bill Holdship article from Creem magazine, October 1984. (Photos by Bob Gruen.)

Holdship spoke for a lot of older rockers who now questioned activism’s value, especially related to music. First critiquing The Clash as “armchair activists” who should emulate Ernest Hemingway—or George Orwell—in the Spanish Civil War by donning actual military uniforms to fight for their Central American causes, Holdship then flipped to embrace resignation: “As I grow older, I’m beginning to believe that there simply are no political solutions . . . Things rarely change.”

Holdship’s fatalism echoed UK writers like Martin and Barber whose “I’m older and wiser now” stance came off more as self-serving cynicism rather than insight. One can almost hear them straining to vanquish their younger, more idealistic selves.

Martin mourned the “seven long years since I first ripped that T-shirt, scowled that scowl, and danced that dance.” Barber evoked “the good old days“ when “we could actually believe that The Clash were some sort of radical force,” claiming Strummer “still seems to think he can shoot Margaret Thatcher dead by commanding one of his guitarists to thrum an E chord like a machine gun in the direction of the House of Parliament.”

Their dismissals seemed aimed as much at reassuring themselves over convenient choices made and dreams abandoned as assessing the band’s performance. Nonetheless, Holdship’s “million-dollar question” for Strummer hit home: “What does an orange Mohawk have to do with changing the political structure in the 1980s?” Holdship suggested that symbolic actions were not enough. In this, he—as well as Martin and Baker—surely had a point.

“Music isn’t a threat, but the action that music inspires can be,” argued Chumbawamba, a group of Crass devotees then building its own underground following.

As any self-aware punk might agree, 1984 was no time for anyone to expect a band to fight your battles for you. Strummer told Holdship he wanted fans to “get out from under our shadow, be your own person. I’m proud to inspire people, and from then on, they should take it from there.” This, of course, could be a cop-out. What exactly was The Clash doing to aid its fans in making this crucial next step?

Yet Strummer’s patience with tough questions won Holdship over, as did the passion of the band’s performance. While the writer wasn’t impressed by many of the new songs, he allowed “the new band sounds tighter and better than the old lineup.” Holdship grudgingly granted, “Maybe Joe Strummer was right. Maybe we do need The Clash . . . A little optimism ain’t a bad thing.”

One of the themes Strummer hammered with Holdship was the band’s antidrug stance, as he did consistently on the rest of the tour: “We’re not born again or anything like that. All we want to do is think clearly, and you can’t think clearly on any drug. And I’ve found that my life is much better.”

There were broad implications here. After the rousing DC show, Strummer had once again linked drugs to Reagan’s ascent, while paying tribute to a punk antidrug movement inspired by the DC hardcore band Minor Threat: “I’m pleased to see there is a straight edge scene . . . It is something separate from us, yet we happen to be traveling on parallel paths. It reinforces my belief that it is right.”

Ironically, at that moment, another antidrug movement—one far less grassroots in conception—was taking shape within a building less than a mile away at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW. After a visit to a Brooklyn drug rehabilitation facility during the 1980 campaign, Nancy Reagan had made fighting drug abuse her central cause as America’s first lady.

“Just Say No” was about to become her mantra. Legend suggested Reagan came up with it spontaneously in response to a child’s question. According to The Yale Book of Quotations, however, the slogan “closely identified with Nancy Reagan” was “originated by the advertising agency Needham, Harper & Steers.”

Agency representative Carolyn Roughsedge told the New York Times in 2016: “Bob Cox and David Cantor came up with ‘just say no’ because that’s what a little kid would say.” When Mrs. Reagan visited the agency in October 1983, “they presented it . . . and she absolutely loved it,” Roughsedge said.

The Just Say No campaign would be announced later in 1984, and clubs touting the slogan would soon sprout at hundreds of schools around the country. Nancy Reagan’s initiative was surely well intended and driven by genuine concern about a very real problem. Meanwhile, however, her husband moved forward on a more ominous tack.

In October 1982 Ronald Reagan had revived the “War on Drugs,” an initiative first launched by the Nixon administration for reasons that went far beyond concern for public health. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people,” former Nixon domestic policy chief John Ehrlichman told Harper’s writer Dan Baum in 1994. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and by criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

This initiative had more than symbolic consequences, Ehrlichman made clear: “We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.”

By the time these quotes surfaced in 2016, Ehrlichman was dead, and his family disavowed his words. In any case, the “War on Drugs” revived by Reagan would have a far more dramatic effect than “Just Say No”—one not so far from what Ehrlichman suggested.

This was not the only disturbing twist in this particular tale. As Reagan denounced drugs, some of his contra allies—with US support cut off by a disapproving Congress—were using cocaine sales to help finance their attacks on the Sandinistas.

Some of these drugs made their way to American streets as something new called “crack”: cocaine cooked solid then chipped into rocks meant to be smoked, not sniffed. Crack would soon generate panicked headlines as a cheap, highly addictive drug spreading violence and community disintegration.

While crack’s carnage was very real, the most destructive drugs in American society remained far more mundane: alcohol and tobacco. The Reagans were painted as hypocrites by some observers for opposing drugs, yet indulging in martinis and the like. The Clash shared this contradiction. Strummer’s love for alcohol and tobacco was well known. He saw nicotine as a spark for creativity and alcohol as a “revolutionary drug” because it got people talking.

Clash biographer Salewicz even suggests that as Strummer’s pot use dropped in 1984, his alcohol consumption went up—and he was not alone in this excess. While the band limited alcohol before a show, afterward copious amounts of it helped them wind down, often in bars where they encountered their fans.

For Strummer, this was part of his punk ethic. He liked being accessible to his audience, often listening more than talking. Yet the toll of such heavy drinking was significant. White’s girlfriend would josh him at the end of the US tour about the belly he had developed despite the almost daily shows. The abuse of bodies with alcohol, lack of sleep, bad food, the grind of constant traveling . . . it was bound to take its toll. This was especially so for Strummer, still harboring the grief over his father’s death as well as aching over the distance from his wife and child.

Perhaps having a young daughter was making Strummer more sensitive to other issues, as suggested by “Sex Mad War.” Like many of the best Clash songs, the tune was a bit of glorious jumble: whip-sharp punkabilly with a blistering feminist message that Strummer underlined nightly with stinging onstage commentary.

Aware that The Clash was seen as a “lad’s band” with a mostly male following, the Clash frontman began to talk about a “new man”—or “a new human being’’—who was “antiracist and antisexist.” Strummer encouraged female involvement, pausing to honor “some brave girls down here” in front of the stage in Eugene, Oregon.

That night Strummer also expressed his hope “that some men here will realize that pornography is rape, which the women already realize . . . and they can’t walk [safely] in the dark!” He was echoing feminist activists such as Robin Morgan who asserted, “Pornography is the theory and rape is the practice,” and Andrea Dworkin who saw it as part of what she would later describe as a “war on women.” This line of argument could be disputed—and was, even by other feminists—but regardless, “Sex Mad War” was not your average rocker.

The song also resonated in a moment where concerns about sexual violence were rising on college campuses, the main venues for the Clash tour. Strummer had even rewritten the opening lines—“Going to the party / never made it to the party / she’s gone”—making the song even more relevant to college communities where “Take Back the Night” marches were becoming more widespread. If the musical vehicle was hardly groundbreaking, the message was—at least for a popular all-male rock group—and the song evoked an eerie atmosphere of violent foreboding with jagged stop-and-start guitar, bass, and drums.

At least some Clash members, however, felt a twinge of conscience about the tune. Sheppard: “We didn’t treat women that well, did we?”—a sentiment sadly seconded by White. If The Clash rhetorically was miles away from rockers such as Mötley Crüe—who Creem’s Holdship scorched as “morons” yelling out witticisms like “We love fucking the girls in Detroit because their pussies taste so good!” from stage—it was not entirely divorced from the groupie scene.

White had started out keeping to himself, excited by touring. He soon grew wary: “The great United States of America—miles and miles of synchronized bland nothingness. For me, it got essentially boring pretty quick.” White also bristled at controlling behavior like the enforced regimen of certain music and artists on the tour bus.

Playful high jinks could help ease the tension. For example, the Mohawk imagery that dominated on the tour’s T-shirts, posters, and handbills took on a life of its own. In Hartford, the band started up a good-natured debate with its Texan road crew. “One of the guys had really long, luxurious black hair,” Sheppard recalls. “We started kidding him in the bar: ‘You should have a Mohawk.’ So he said, ‘Well, hell, if you give me a thousand dollars, I will.’ In five minutes, there was a thousand dollars on the bar—and he crapped out. He wouldn’t do it.”

Just then, however, one of the truck drivers agreed—if the money could go to his favorite charity, “which was homeless [children], or something like that,” Sheppard continues. “So we all trooped off to this local bar that had a stage, set up a chair, and starting giving Mohawks to all and sundry.”

The same had happened a couple nights earlier, before the band’s April 22 show at the Philadelphia Spectrum. The band found themselves sharing the same hotel as the Grateful Dead, whose own hair could stand a bit of shearing—or so ran the thinking in the Clash camp. Sheppard laughs: “Kosmo went on a Mohawk spree that night. By the next day, he had a bagful of hippie hair that he’d cut.” But the Dead’s locks were not among the trophies.

Not all diversions were as benign, however. As tedium set in, and alienation from the rest of the band grew, White began embracing casual sex with the band’s followers. Egged on by twin groupies, White even indulged in that most clichéd of rock star antics, trashing his hotel room and hurling a TV out the window. He had to pay for the damage, getting a Vinyl tongue-lashing to boot.

White had taken matters to an extreme, but he was hardly alone in acting out. Given that hedonism had long been one of rock’s core pursuits, this was hardly headline news. Still, a banner of “If it feels good, do it” hung uneasily on a band touting “a new antisexist man”—and Sheppard and White knew it.

One man stood at the center of the operation, carrying immense weight. How was Joe Strummer doing? It was hard to tell, as he tended to keep his deepest thoughts and feelings to himself. The singer may have been taking his own measure as much as the band’s in telling one reporter, “Yeah, let’s go for the top, let’s take it all on at once—that’s always been our speciality!”

Occasionally, telling bits would slip out. Coming offstage after a frenetic, soul-drenched New Jersey show in late April, a momentarily unguarded Strummer told someone close to the band, “You know, sometimes I almost believe in this!” The self-doubt exposed by Johnny Green had clearly not disappeared.

Salewicz reports that after the Long Island show Strummer shared his darker side with longtime friend Jo-Anne Henry: “The death of his father was still in his thoughts, and now Joe was beating himself up for being away while Jazz was a baby. ‘I could be any bloke going off and leaving her,’ he said,” Henry recalled. “Jazz being born brought up tons of stuff about his childhood . . . Deep down he seemed to be in a really awful state. There was this anger that he was not able to let come out, the swirling emotions inside him that he couldn’t admit to.”

As with the others, touring wearied Strummer. He had to summon enormous amounts of energy and passion every night. In one TV interview in late April, Strummer was asked how he felt about the new band. Flanked by the other members, Strummer responded: “Great!” Then, as if to underline his point, he leaned forward and repeated even more loudly: “GREAT!” His defiant response seemed intended to convince himself more than anyone else.

Behind this shout, Howard suspected, was a person struggling to deal with a growing array of demons—personal, social, and professional—that the relentless tour schedule wouldn’t allow a chance to address. “He was getting quite mental, quite desperate, and he was drinking an awful lot,” Howard says.

Yet the near-nightly shows seemed to help Strummer focus. Whatever his private qualms, the singer didn’t let them show onstage. Even critics rarely found Strummer’s performances anything but convincing.

Changing things up helped with this. Three weeks into the tour, another song disappeared from the set: “In the Pouring Rain.” A live version from the April 14 show at New York’s Hofstra University suggests why. While featuring powerful lyrics and music that blasted off after the chorus, the song was hamstrung by a clunky beginning. Other bands, notably Gang of Four, had overlaid dark social observations atop dance beats—a sound that some writers took to calling “plague disco.” But the chunky, repetitive funk riff chosen to drive home “Rain’s” message actually served to undercut its intense lyrical bent. The result seemed a bit herky-jerky and off balance, having never fully blossomed from its original demo.

Shaking up the set a bit, Strummer got the band to work up “Broadway” in its place. Since the new band had never played the song, “We had to go out and get a record to figure it out!” Sheppard laughs. At the same time, “Junco Partner,” “Jimmy Jazz,” and “Koka Kola” were also brought up from the basement. None were among the stronger of the band’s catalog—not really a match for the newly dropped “In the Pouring Rain,” or maybe even “We Are The Clash” and “Glue Zombie”—but they added variety, helping Strummer keep his performing fresh.

Unlike with “We Are The Clash,” Sheppard wasn’t satisfied to see “Rain” disappear: “Some songs have space, you can find your way into them, do you know what I mean? I found the way in on ‘Pouring Rain.’” Stripping out Strummer’s rhythm guitar, Sheppard had experimented with a different arrangement that opened with graceful, descending chords. Slowly shaping it up, he’d shared his ideas with White and the others during free time at sound checks.

As the tour wore on, Strummer leaned on his absurdist humor. At one show, he dedicated “Armagideon Time” to “anyone who has turned down a Hostess Twinkie and felt the better for it.” In a stiflingly hot Chicago club, he kicked off “White Riot” with a wry query: “What I’d like to know, judging by the temperature in this room—if this is the Windy City, where’s the fucking wind?”

Above all, Strummer sought solace in his Clash platoon—or at least his romantic conception of it. In New York, he motioned to the rest of the band, telling the crowd, “We ain’t pretending to be friendly with each other when we are standing in front of you. When we go into the back room, we actually are friends. I tell you a lot of famous groups hate each other’s guts, they won’t even get in to the same car with each other . . . I don’t want to go forward into that situation.”

When the entire band was interviewed by a cable TV show in Toronto, Strummer took this one step further. Asked about his personal life, the singer blurted out, “If you are really serious, you haven’t even got time for a personal life!” Later in the interview, he added, “I have no friends.”

The interviewer asked the obvious follow-up: Why not? “Because when we started this group we realized we had to dump everything that we’d had previous, and that included everybody we’ve known, everybody we’d lived with.” As Simonon seconded that, Howard jumped in: “Yeah, that’s why we don’t need a personal life outside this group, because this is it. This is it.”

The reporter probed: “Why don’t you have any friends, is it because your views are so pure that you can’t let in any outsiders?” Strummer nodded: “You can, but it is weakening in some way. You’re getting at it with what you said about ‘pure’—when we put the group together, we tried to reinvent the world from scratch.”

The journalist persisted: “But when you reinvent the world, you have to invite some other people to come with you . . . ?” Strummer clenched a fist and launched an empathic rejoinder: “Yeah, but I mean ‘reinvent the world’ because we are looking for an idea, not because we are throwing a party!”

The vision Strummer and the band put forward was a demanding one—the platoon, whole unto itself, tight-knit, self-sustaining, unstoppable. The image presented in the interview was not exactly untrue. The band had surely come together musically, as well as somewhat on a personal level. For example, Simonon and Sheppard had bonded enough for a jealous White to notice.

However, there were worrisome elements. Strummer seemed to share his inner life with no one in his band. By pushing down the feelings, channeling it into his performances, he might be a riveting frontman—but was he happy, healthy, centered? If not, his creative momentum was not likely to be sustainable.

Another unresolved tension remained. After soldiers endured punishing boot camps, real effort was made to build group solidarity. This was not so in The Clash, where boot camp never ended. As King ruefully admitted, “Bernard wanted it uncomfortable, he wanted it vital and raw, at each others’ throats. He kept you edgy, on your toes—he would antagonize just to make something happen.” If this approach could accomplish some things, it hardly fostered unity.

Other factors also tended to divide, including money—specifically, why there wasn’t more of it, especially for the newer members. White tried to get Sheppard and Howard to join him to press Rhodes for more pay midtour. “Fucking socialism in action, I thought,” chortled an unrepentant White later. Finding no takers, the guitarist went to Rhodes anyway, only to be flatly refused and left feeling like a “greedy capitalist.”

At the band meeting later that day, White expected to get roasted by the irascible manager. To his surprise, Howard instead became the focus of fire from both Rhodes and Strummer for supposed lack of commitment, in what White later described as a “mafia meeting.” Invited by Rhodes to either shape up or find new employment, Howard walked out.

While Howard was brought back in time for the evening show, the incident suggested the internal band situation was more complicated than Strummer let on. That was underscored when White and Howard came to blows onstage at the May 25 show in Denver. Henry David Thoreau—one of those uniquely American “lunatics, individuals, and madmen”—had argued, “Live your beliefs and you can turn the world around.” If so, how well was The Clash doing this?

If aspects of the new Clash appeared dodgy, the music was not. The strongest proof was a refurbished “In the Pouring Rain” which returned to the set in Dayton on May 8. There could hardly have been a more appropriate moment for its reappearance, as the show began a swing through America’s Rust Belt.

The song had been inspired by what Strummer called the “ghost towns” of the northern UK, devastated by an increasingly globalized economy, accelerated by Thatcher’s polices. It fit the similar doldrums of this once-vibrant heartland. This descent into rust had been worsened by Reagan’s policies. A global “race to the bottom” was underway, one that slashed American jobs in favor of foreign workers who received slave wages while corporate profits boomed. Though cheaper consumer goods also resulted, this was little comfort for previously comfortably middle-class workers who now couldn’t afford even inexpensive products.

“Rain” was immensely strengthened by the revamp. The verses breathed and built momentum throughout the song. Even if the postchorus blastoff was missed, something extraordinary was coming together, a song worthy of its weighty subject matter: the wrenching pain and dislocation felt in such hard-hit communities.

Strummer carefully linked Rust Belt tragedy to the ongoing struggles at home, telling one audience that the “situation is bad in the UK, just like this country.” Back on the British picket lines, neither side had been able to strike a knockout blow. A grim war of attrition was developing, a situation that might not favor the miners.

Realizing this, Scargill decided to target the Orgreave coking plant with mass pickets. Thatcher feared this would become a reprise of “The Battle of Saltly Gate” where striking miners joined with other workers to close the Saltly coke works in Birmingham and effectively win the strike in 1972. Determined to prevent this, the Tory leader put pressure on the police to increase roadblocks to stop flying picketers, and embrace mass arrests and other rougher tactics—effectively outlawing dissent and easing the way for brutality.

Locked in their alternate reality, The Clash was unaware of much of this. The musicians were now racing toward the end of their sojourn in the US—a tour that, despite the obstacles, had been a significant success.

Strummer’s exhaustion was starting to show. Introducing “In the Pouring Rain” in St. Louis on May 21, he was boozy and bereft: “All the towns are dead! I mean it! I’ve been in more towns the past eight weeks that I can even think of and they are all dead! They are all dead in Europe, they are all dead everywhere! This is ‘In the Pouring Pouring Motherfucking Pouring Rain,’ jacko!” His outburst muddled the song—not all towns were dead, only those whose hearts had been ripped out by free-market policies—and suggested the singer’s ragged spiritual state.

The performance was nonetheless potent, and Strummer showed no further signs of strain that night. He was back on message over the week, announcing “Rain” as “news straight from England!” Audience tapes capture the fan reaction: in St. Louis, one deems the song “fucking great”; in Eugene a few days later, a woman can be heard gasping, “That was beautiful!” at the song’s end.

So it was. With three weeks of continued growth and polish, “In the Pouring Rain” had become a stunning achievement, on the level of truly great Clash songs like “Straight to Hell,” “Complete Control,” and “White Man in Hammersmith Palais.” Sheppard’s descending chords drew listeners into the tale, and White’s leads added to its pathos. The guitars played off one another, conjuring a sense of utter desolation, as if lost in a driving storm, drenched to the very soul.

Could there be a way to turn this tide, a current that seemed as relentless and unforgiving as the English weather? Perhaps. In the US, it was becoming clear that Mondale—a longtime union supporter who spoke passionately against Reagan’s economic policies—was to be the nominee of the Democratic Party. In May 1984, he also pledged his commitment to ending the nuclear arms race, reaching out to activists like Helen Caldicott to press the issue on the campaign trail.

Reagan’s team was watching closely. National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane later admitted, “We took [the nuclear freeze] as a serious movement that could undermine congressional support for the nuclear modernization program and potentially a serious partisan political threat that could affect the election.” It would not be easy, but most observers thought Mondale had a fighting chance to defeat Reagan, denying him a legacy-sealing victory.

Meanwhile on the UK picket lines, pressure was growing day by day, as a decisive confrontation loomed. As in America, a bitter contest for the country’s future was underway. Who would emerge victorious remained to be seen.

The Clash was winding up its US campaign, bone-tired and homesick, but justifiably proud. In Seattle, Strummer sparred with overzealous security while shepherding a fervent crowd so no one got hurt. Communing with three thousand souls packed into the Paramount Theatre, the singer led his bandmates through a blistering set.

After four months of intense touring, the group was a rock dynamo, with new songs played with a ferocity and skill that made the promise of an amazing new record seem real. The band’s eighty-minute set was clockwork paced, with the final half hour a breathless sprint through highlights of the band’s catalog.

Just before the show—the second to last on the tour—Simonon mailed a postcard to old friend Moe Armstrong in California: “Howdy! Well, after two months and 20,000 miles of American roads, we are now ready for home!”

Were they really ready? Outwardly, the collective mood remained as bullish as ever. “We certainly don’t fall into the category of people that are willing to shut up,” Vinyl offered backstage at the University of Oregon. “We like to get in an argument, right? Once you get a big argument going, you get all kinds of people involved, and then you get—maybe you get a few answers.”

But had the band found its own answers? The unit was not truly unified, and a costly bill for unresolved issues would soon come due. Meanwhile, the band was headed back to a country on the brink of something close to civil war.