Introduction |

The Roman theatre in Orange with its towering back wall of ochre stone, the only one to survive in Europe, was once an entertainment centre for the flourishing colonial colonies of southern France. I sat on the top row, where the rabble used to sit, and listened as the disembodied voice from the audio guide told me that at first the Romans had followed the Greeks and Etruscans, performing serious drama, but later they grew tired of tragedies, preferring jugglers, clowns and gymnasts. Later still, the shows were devoted entirely to pornographic displays, until the early Christians came along, smashed up the theatres and banned all secular entertainment. Distant in time though these events might be, they seemed tellingly to prefigure a possible future for contemporary culture. As pornography floods the internet and celebrity culture swamps the global media, perhaps it is only a matter of time before Evangelicals or Islamists bring a decaying Western culture crashing to the end it deserves.

Late Roman culture was in fact by no means entirely given over to trash any more than is our own. After the Romans, with their mosaic flooring, central heating and vineyards, left Britain, the island took 500 years to recover. Today, innovative culture and learning flourish in all sorts of places. Religious fundamentalists have certainly denounced contemporary Western consumer societies as decadent. However, a society is not a single organic entity like a vegetable marrow, but is a complex conglomeration of multiple systems and formations. Some may be flourishing, others in decay. Sometimes new forms grow from the dead, just as the florid vitality of a cemetery’s ivies and flowers draws nourishment from human remains. Contemporary culture is diverse and contradictory, yet even if the Western world avoids being plunged into a new dark ages in the near future, a sense of anxiety and melancholy pervades cultural comment. Pundits and politicians alike view the society of consumption with ambivalence.

Consumption was a vernacular nineteenth-century term for tuberculosis, then an incurable wasting disease. It would be tempting to suggest that we do in that sense live in a society suffering from consumption. The individual suffering from consumption experienced periods of exaltation and sometimes creativity. John Keats and Emily Brontë owed the intensity of their writing in part to their fatal illness.

By the time they were writing, markets were already developing for the commercial provision of the arts and ‘entertainment industries’. This produced a division between what came to be seen as ‘high’ art and ‘mass’ culture. That division continues to set the terms of cultural debate.

In the following chapters, I focus on the emotional commitment audiences and users bring to the objects of their desire and to the performances in which they find meaning. By focusing on this, I hope to transcend the division between ‘high’ and ‘low’. In practice, the tastes of many, perhaps the majority of individuals, do cross this boundary, yet the division between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture continues to set the terms of debate.

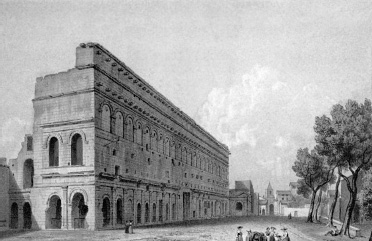

Figure 1: The Roman theatre at Orange in the eighteenth century.

Figure 2: Today the Roman theatre is once again the arena for opera and other spectacles.

This divide has always been moral and political as well as aesthetic. Two well-established positions set the parameters. On one side stand those who bewail the ‘dumbing down’ of culture. This was the position taken by Frank Furedi in his Where Have All the Intellectuals Gone?, published in 2004. Furedi argued that the role of the intellectual and respect for the figure of the intellectual have been undermined as education has been transformed from a search for truth to a managerial training. Students are to be inducted into a role in which they will not question the utilitarian status quo – the idea, for example, that the chief goal of society is economic expansion. Furedi further argued that contemporary society is characterised by a deep philistinism – a philistine being an individual ‘devoid of liberal culture and whose interests are material and commonplace’. He illustrated this philistinism with the words of former British education minister, Charles Clarke, who expressed the opinion that the teaching of history and indeed any sort of ‘education for education’s sake’ was ‘a bit dodgy’. Furthermore, suggested Furedi, ‘democracy’ in the allegedly democratic societies is little more than a façade masking deep social inequalities. This façade is partly created precisely by the philistine and supposedly ‘anti-elitist’ suspicion of the pursuit of learning, and includes a preference for mass culture over high art. Traditional ‘high art’ is also, after all, ‘a bit dodgy’.1

Contempt for learning as an end in itself is one aspect of a rhetoric that claims to speak for the majority, presenting this as democratic, when it is in fact merely populist. The populist is an important ally of the philistine, aiming to speak for and include ‘ordinary people’, to cater to and share the tastes of the mass public and to respect the authenticity of the ordinary. There would be nothing wrong with that – on the contrary – were it not that it slides into the rejection of anything that is assumed to be above the heads of ‘ordinary people’: the patronising assumption that they are too thick to enjoy anything complicated. A love of classical art is cynically denounced as snobbery. Minority tastes for complex works are viewed with suspicion as pretentious and ‘highfalutin’.

Such a position can masquerade as progressive in speaking for the majority. Yet surprisingly often it is related to a second ‘progressive’ view that deems cultural works acceptable only when they produce the right attitude of mind in their audiences. For example, in March 2004 another former education minister (and, like Clarke, a member of the Labour Party), Estelle Morris, was invited, when she became Minister for the Arts, to guest edit the cultural section of the left of centre magazine The New Statesman. As minister, Morris understandably focused on issues surrounding state provision. Predictably too, the articles she commissioned privileged ‘inclusion’: a review of a play performed by children with learning difficulties; an assessment of changing attitudes towards black and minority performers; a debate about the value of the Arts Council. She needed, she thought, to ‘cover everything: each of the art forms, nothing too London based, a balance of men and women, and a proper acknowledgement of the diversity of the arts sector’. All perfectly acceptable, if rather bland, and speaking for all sections of society – and displaying the right social attitudes. The minister’s choices illustrated not that ‘political correctness’ is wrong in promoting neglected sections of society, but in censoring out anything deemed too unacceptable, effectively too radical.

But as Hans Arp, the Swiss Dadaist sculptor, once said: ‘Art just is.’ It cannot automatically be recruited to a progressive – or for that matter a conservative – agenda. The Estelle Morris agenda is not culture; it is social engineering. Also, as Furedi suggested, the well-meaning intentions of the Estelle Morrises of this world succeed only in being very patronising. As an Afro-Caribbean student once expressed it after a lecture on modernism: ‘why have we been excluded from all this?’

The populist critic takes for granted that the ‘ordinary people’ can never warm to works that he (himself almost certainly the product of advanced higher education and with a doctoral degree) has designated as ‘elitist’. But if whole sections of the population have never been to an art gallery or listened to Beethoven this is at least partly because the educational system and commercial pressures act to keep them away. A crippling sense of ‘it’s not for the likes of us’ is reinforced by a narrow idea of ‘relevance’: the belief that what is designated as high culture can never mean anything to working class or ethnic minority students.

Frank Furedi was equally critical of a relativism that rejects any cultural hierarchy – the idea that some cultural works could be better than others. Yet the origins of cultural relativism were in themselves intended as progressive or potentially progressive.

Until the 1950s a strong boundary between ‘high’ art and popular culture was maintained, along with an assumption that ‘great art’ was to be the more valued. F. R. Leavis, for example, was a leading advocate, both before and after the Second World War, of culture, specifically literature, as a realm in which there were absolute standards of excellence, and which expressed absolute moral values. In the 1930s he warned of the dangers arising from the massification and commercial exploitation of culture and in his critical works on English literature he defended many of them as great moral texts. Above all, great art taught universal values. It had to have a universal character. The plays of Aeschylus (or indeed of Seneca) were as relevant today as they had been when written.

The 1960s saw the rise of cultural studies in universities. This pioneered the analysis – not necessarily the uncritical endorsement – of popular forms. Going beyond television and film to include the study of ‘subcultures’ such as teddy boys and later punk, the new cultural research sought to explain their appeal and investigate their social meanings. This project not only discovered new objects of research but also had different goals, being more interested in the effects on audiences of mass culture and what new forms said about the society in which they appeared than in the quality of paint or the humanistic moral message of a given work. This was a step away from the detachment that had long been considered the proper stance when confronting a work of art. The new generation of cultural researchers were interested in how the audience felt.

This emphasised the subjective element in the reception of culture and it followed from this that the new researchers effectively broke with universalism. Frank Furedi defended the idea of universal truth and criticised the way in which this was abandoned in favour of relativism – the idea that there is no ‘truth’ but only a plurality of ‘truth claims’, all or none of which may or may not be valid (but which even if they are not may somehow still be emotionally valid). The development of relativist views – one aspect of what came to be loosely termed postmodernism – by influential writers, perhaps most of all Michel Foucault, was essentially an attack on the whole Enlightenment project, the belief in reason and progress, and in particular on its Marxist variant. In view of the history of the twentieth century such disillusionment is understandable, but to abandon all effort to find common ground and a common cause, and to reject also the idea that any one assertion can be truer than any other, is in the end to endorse a Hobbesian view of human life as the war of all against all, and to reproduce at the level of thought and cultural production the competitive anarchy of capitalism.

In the 1970s the ‘new art history’, following in the footsteps of cultural studies, ‘prioritised social and political contexts over older concerns of authorship and appreciation or connoisseurial value’.2 In literature too, claims about ‘objective’ standards of beauty and perfection of technique were supplanted by the view that such objectivity was false, and served largely to prioritise the work of an elite over that produced by women, ‘minorities’ and working-class writers.

One variant of the new approach was to claim that there can be no hierarchy of art forms, that – to use a clichéd example – Beethoven cannot be judged better than The Beatles, but simply different. Yet it is quite possible to recognise the differences and the merits of both while at the same time arguing that Beethoven really is ‘better’ than The Beatles, because, for example, his music addresses a wider and deeper range of thought and emotion than the Fab Four; or, on the other hand, to criticise The Beatles’ sometimes fey whimsy, but also the clunking facetiousness of Beethoven at times.

In any case, Beethoven is today one of the most popular of all composers, while the fictions of many writers who belong to the ‘canon’ of the classics, such as Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, have proved to resonate with contemporary readers, encouraged by television and film adaptations to return to the books themselves. The narratives remain fast and compelling and their meaning, if not universal, at least transcends a century or two.

It would not be difficult to develop an argument suggesting that Pride and Prejudice is better than Harry Potter, but this would be to move outside the parameters of what is polite to say. The ‘soft’ policing of cultural taste means that understandably no one wants to appear a snob. By contrast, it is fine to say that you watch The X Factor because it is so camp. Cultural positioning of this sort has nothing to do with criticism, but is a function of social fashion; which may also have been the reason for Charles Clarke’s remark about history.

The serious study of popular culture took on a systematic form when in 1964 Richard Hoggart set up the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University. This was an attempt to widen the parameters of cultural debate – and to challenge not only the divide between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, but also that between the active producer and passive consumer set up by the cultural theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, discussed later. Yet by the 1980s the enterprise had too often degenerated into an uncritical endorsement, by at least some cultural researchers, of almost any popular form and an automatic self-distancing by tastemakers and social elites from anything approaching ‘elitist’ culture. ‘Elitist’ and ‘elitism’ have become simply terms of abuse, a label for those who are said to consider themselves superior to other people and who sneer at the low tastes of others, but who have no rightful claim to their positions of cultural power. This seems to be due to a confusion of two meanings of the word: ‘elite’ in the sense of individuals or groups who excel in some field – for example, a great musician or scientist, each of whom could be said to belong to an elite of the brightest and best in that field; and ‘elite’ simply in the socio-economic sense of belonging to a group in society who are privileged not on account of talent and hard work, but merely by reason of inheritance, whether of wealth or lineage.

In any case, the term elitism came originally from the idea of election. The elite consisted of persons who had been chosen, which implies a democratic process. Surely there is nothing wrong – on the contrary – in acknowledging the outstanding achievements of certain individuals; of allowing, for example, that Pavarotti was a great singer who sang better than most other singers. Yet today, to endorse ‘elitism’ is allegedly to be undemocratic. It is also old fashioned and uncool, to the extent that politicians, those weather vanes of the fashionable, might be more likely to cite Harry Potter than Trollope or (heaven forbid) Proust as their holiday reading. One can only feel satirical about these pretentions, when at the same time many cabinet ministers attended private schools and when it is virtually impossible to succeed in the media industries without an Oxbridge degree.

No one seems to have noticed that the celebrity culture to which craven obeisance is paid is also, of course, entirely elitist. It bears no relation even to a meritocracy, since individuals are shot to fame and notoriety often for no other reason than their novelty or, at best, on the basis of a charismatic personality or that most undemocratic of attributes: beauty, or striking looks. And if television programmes or sports with high ratings and huge followings crowd out the less popular, then this too is considered democratic, when it may be rather the tyranny of the majority.

So to object to the use of ‘elitism’ as a form of condemnation is not a simple reversion to the position that high culture is better than mass culture. The objection is to the bad faith and disavowal with which it is used and its lazy failure to admit that some artistic works are better than others, or at least that it is legitimate to make a case for discrimination.

Some postmodern relativists are, or were, not content simply to claim that all cultural forms are different and cannot be compared. One popular way of expressing this is to claim that if Shakespeare were alive today he would be writing soap operas. There is merit in this claim to the extent that Shakespeare wrote for a popular audience and for profit in his day and might well have embraced the many virtues of the soap opera format. On the other hand it seems unlikely that future generations will be reading the scripts of East-Enders in 500 years time. As literature they simply do not stand up.

Nevertheless, there were postmodern fundamentalists who promoted a populist view of all high culture as inherently oppressive. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, authors of a scathing attack on American mass culture in the 1940s, were the enemy. In The Dialectic of Enlightenment they had denounced mass culture as a form of brainwashing. It pacified the masses and induced a false consciousness that prevented the proletariat from engaging in revolutionary struggle. Their postmodern critics judged the argument as illegitimate since it was, they maintained, uttered from a position of high-minded, patrician contempt.

An individual’s (or a group’s) tastes are certainly influenced by class position, upbringing and education. Yet to argue, as John Fiske did, that ‘taste is social control and class interest masquerading as a naturally finer sensibility’ positions an elite in permanent control of high culture and everyone else – the ‘masses’? – the working class? – as incapable of appreciating what is labelled as high culture. This is also a political project: the idea that any meaningful aesthetic judgements are possible must be destroyed in order to destroy the hierarchy of value implied in the judgement of art. This is considered necessary because it is cynically assumed that to judge a cultural work is also to judge – morally – those who like it. If you read Proust you are a snob; if you watch EastEnders you are a man (or more likely, woman) of the people.

These are themselves, of course, moral judgements. To take up such positions fails to acknowledge that individuals may appreciate both. It also ignores how it is neither a cultural elite nor a mass audience that controls taste, but to a large extent commercial interests.

It may be that Fiske himself has moved on from the rather ludicrous positions he took up at the end of the 1980s. Such judgements, however, filtered down into the broadsheet press and journalism, to the extent that in 2011, for example, the British Observer devotes most of its arts section to popular music and celebrities.

To position ‘low’ against ‘high’ as crudely as Fiske did assumes that not only audiences but art forms themselves can never migrate from one category to another. Yet cultural works are no more static than taste itself. In pre-unification Italy, for example, opera was a popular form, expressing in works such as Verdi’s Nabucco revolutionary nationalist aspirations. In Brussels, in 1830, a performance of Daniel Auber’s La Muette de Portici, the plot of which concerned an uprising against the Spanish, inflamed the audience to such an extent that they rioted, hanged the Spanish representative from the nearest lamp post and set in train the revolt of this part of the Netherlands against Spain, leading to the formation of modern Belgium.

The contemporary view of opera as ‘elitist’ (perhaps particularly in Britain) has more to do with the expense and difficulty of obtaining seats, and its association with corporate hospitality and wealth in general, than with the opera form itself. The content of the majority of operas is perfectly accessible and the reverse of ‘elitist’, since it combines catchy tunes with romantic and melodramatic plots; the Puccini aria ‘Nessun Dorma’ was even chosen as the theme tune for the 1990 football World Cup, held in Italy, the home of opera, and topped the charts as a result. More recently an experiment by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, when tickets were offered at much reduced prices, resulted in a new, different and enthusiastic audience. Filmed performances of the New York Met’s productions have also been very popular.

Another example of movement from ‘low’ to ‘highbrow’ is cinema in general and ‘film noir’ in particular. The French cinema journal, Cahiers du Cinéma, coined the label after the Second World War to refer to a series of mostly Hollywood films made during the 1940s, but shown in France only after 1945. Whether film noir constitutes a genre has been disputed. Typically, nevertheless, these films combined thriller plots, crime, femmes fatales and weak heroes in often melodramatic narratives. Many, though not all, had originally been made as low-budget B-movies and were ignored by critics. In the 1980s these movies were revived on late night television and this may have been what aroused the interest of students and critics, their attention drawn to these forgotten works. A whole academic literature on film noir developed and films such as Double Indemnity, Cat People and The Big Sleep were subjected to advanced critical analysis. Their moody, downbeat and often misogynistic tales could be interpreted as expressive of a post-war mood of cultural pessimism and reaction, while the edgy glamour of their off-beat photography, unusual looking stars (Joan Crawford, Robert Mitchum), strange camera angles and use of mirrors and shadows became a widely recognised style. To watch film noir now became a matter of connoisseurship rather than escapism. Film noir became highbrow, became high art rather than low culture.

Equally dramatic was the move in the opposite direction of impressionist and post-impressionist painting. Greeted with horror when first viewed in the Paris salon, by the mid-twentieth century the paintings of Monet and his peers had become a staple of popular taste, reproductions found not only on sitting-room walls, but on biscuit boxes, birthday cards, tea towels, jigsaw puzzles and calendars.

The postmodern populists, however, at least in the heyday of postmodernism, refused to recognise the changing status of art forms. Fiske argued that ‘the popular … can be characterised by its fluidity’, as if what is traditionally labelled as ‘high art’ were incapable of ‘fluidity’ – whatever that means. With similar inflexibility, other critics asserted that ‘rigid hierarchical divisions’ are ‘embodied in traditional elite culture’.

The rigid separation of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture assumes that not only cultural forms, but also audiences themselves, are permanently cordoned off into clear and unchanging categories, thus preserving the class system Fiske presumably dislikes. Fiske recognised that an individual ‘may at different times form [different] cultural allegiances’, yet the ‘people’, the ‘subordinate’, remain forever separated from the ‘elite’ by the latter’s insistence on the disciplinary system of aesthetics, which illegitimately tries to establish standards of excellence: ‘Aesthetics is naked cultural hegemony’. If this is the case, then logically no one can ever even write a film review – much less a book, as Fiske himself did – without claiming ‘hegemony’ over his readers. 3

Fiske was also a subjectivist who claimed that the cultural value of a given work lies exclusively in the meaning it has for a particular person’s life at a particular moment. While it is true that every work of art has meaning for the individual who responds to it and that each individual varies in their ability to respond to this or that artwork, Fiske appeared to deny the possibility of any collective aesthetic experience. He also failed to acknowledge that there is a value in understanding cultural artefacts beyond our own subjectivity. Yet cultural artefacts and spectacles are, after all, our history and the history of others.

In a sense technology encourages a solipsistic subjectivism, the individual’s iPod playlist expressing his or her taste and no one else’s. Indeed, iPod owners talk not about ‘music’, but about ‘my music’: the playlist they have constructed. Your tastes express your personality, rather than even joining you to a taste community – although such communities exist and continue to flourish.

Ironically, beneath the claims Fiske made for pluralism and choice (i.e. democracy) lurked – and still lurks – a more sinister agenda. For him, as for Estelle Morris, the determining criterion for art is ‘social relevance’ rather than aesthetic quality; ‘the evaluative work of popular criticism becomes social or political, not textual’, says Fiske. He seems oblivious to the way in which this could lead straight to Stalinist ‘socialist realism’, which I suspect he would not favour. And who decides what is ‘relevant’? Is it John Fiske? The government? It certainly is not, except in the restricted sense of purchase, the ‘ordinary people’, since the consumer can only buy what has been offered by those who run the ‘creative industries’.

Arguments against ‘high culture’ were in part a move to legitimate the academic disciplines of cultural studies and media studies as the study of mass culture, and as such constituted at times rather blatant political special pleading. This was understandable, given the hostility to these new disciplines from those who labelled them as ‘dumbing down’. The populist defence was nevertheless often guilty of crude overstatement. Even more seriously, the arguments as often as not simply inverted categories of ‘high’ and ‘low’ rather than seeking to move beyond them.

Fiske was writing when postmodernism was at the height of its popularity and today postmodernism has waned. Academics grew bored with the dead end to which it led them and simply forgot about it. Its formulations have nevertheless become sedimented into a default cultural posture: Elitophobia. As Furedi partly defined it: ‘the denunciation of “Western rationality” or “male logic” assumes that … the path to truth is above all through subjective experience rather than theorising or contemplating’.4

The importance of Furedi’s arguments notwithstanding, it would be a mistake to present an uncritical picture of the whole Enlightenment project, or mount a seamless defence of universalism. Pope Benedict, spoke as fervently as Furedi for universalism and has on several occasions preached against relativism. Yet his universal truths – or rather beliefs – directly conflict, one assumes, with Furedi’s. Of course, many individuals adhere fervently to the truth of beliefs that cannot be verified. That does not mean, however, that there exist no truths that can be verified. Nor does it mean that no aesthetic judgements can ever be made, for, after all, aesthetic judgements are made all the time in everyday conversation. A meal in a restaurant will invariably include a discussion of the merits or otherwise of the food; friends and bystanders comment continually on the fashion choices made by those around them.

The optimism of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment can appear complacent, to say the least, as for example when Edward Gibbon wrote at the conclusion of his history of the decline and fall of Rome:

The experience of four thousand years should enlarge our hopes and diminish our apprehensions. We cannot determine to what height the human species may aspire in their advance towards perfection; but it may safely be presumed that no people … will relapse into … barbarism… We may therefore acquiesce in the pleasing conclusion that every age of the world has increased and still increases the real wealth, the happiness, the knowledge, and the virtue of the human race.

But reason has not brought harmony to humankind and it can barely be imagined what Gibbon would have thought had he returned to this earth during the Nazi period, or indeed the present day. On the other hand, we cannot abandon reason altogether. We have to persist with the Freudian project of trying to bring reason to bear on the unruly and rapacious realm of the emotions.

There would be no need to revisit this debate, were it not that it continues. A 2011 example of the continued existence of the high art/low culture divide was a debate on the demise of the professional critic in the London Observer. There, Neal Gabler argued that passionate engagement has replaced the reasoned assessment of trained writers and that this amounts to the triumph of populism over an elite of pundits, as ‘amateur’ critics launch themselves across the web in blogs, Facebook, Twitter and a host of opinion sites of all kinds. John Naughton and Philip French disagreed and did attempt to move beyond the high/low division, arguing respectively that deference disappeared long ago and that the divide between elitist critics and ‘ordinary people’ is a false one; but Jessica Crispin of the website Bookslut set the enthusiasm of internet contributors against official critics, the real role of the latter, she suggested, being economic – to sell the product.5 So while Naughton and French strove to move forward, they were still constrained by the very traditional parameters of the other contributors to the debate. It is still the ‘people’ versus the ‘elitists’.

In the following chapters I discuss certain artefacts, practices and performers, some of which are both popular and despised, or at least viewed ambivalently. This raises a further issue: of a general suspicion of beauty itself, of the aesthetic, which subtly relates to both ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

Suspicion of the aesthetic dimension of life has a long history. It has taken a specific form now that we live in a consumer society increasingly viewed with ambivalence and even alarm. So too populism may be added to the Puritanism that surreptitiously informs so much cultural and social criticism. The moral fervour that fuels the indignation of those both for and against high art/low culture seems often related to this suspicion of the aesthetic itself.

Devotees of high culture used to be known as ‘aesthetes’, but the aesthete was always a dubious figure, caricatured as an essentially frivolous character focused on the fripperies of life rather than on serious matters such as politics and making money, and concerned with decoration rather than with meaning. Even if not a dilettante, the aesthete represented the aesthetic approach to life, which was accused of lacking moral depth. Suspicion of the aesthete expressed the traditional separation of the material and the spiritual. Too great a preoccupation with the material world, even in the sense of works of art, was equated with materialism and hedonism.

A further criticism of the ’classic’ aesthete was that he was essentially an individual who already had money, typically a rentier, but possibly an aristocrat and anyway a gentleman of leisure, whose wealth freed him to enjoy the refinements of art. He was aloof from the toiling poor, whose lives were consumed in labour, who were shut out from his rarefied existence, even as they worked to support his way of life and produce the beautiful objects he worshipped. This is certainly a valid point, since the enjoyment of cultural experiences has largely depended on the availability of both education and leisure. What care assistant, working a 60-hour week on the minimum wage, has time to loiter through Marcel Proust’s immensely long novel, In Search of Lost Time? It is, of course, not Proust’s fault if no one has time to read his novel. Often, however, resentment at the terms and conditions of a life of toil are directed at the wrong target: instead of blaming ‘the system’, cultural commentators (who, ironically, do have time to read) focus on those pretentious individuals who sneer at Big Brother and The X Factor. Moreover, as we shall see, Proust himself was for long not taken seriously because he himself was viewed as a dilettante and aesthete.

Yet the advance of technology has saturated the environment with visual images and music and has made available a wider variety of the written word than ever before. Today, the urban, and to a large extent (and in a different way) the rural environment, are more highly aestheticised than it has ever been. In a sense, therefore, today we are all aesthetes whether we like it or not.

In addition, the cultural industries and new media permit the emergence of the fan as a more democratic kind of aesthete. And, although the aesthete has traditionally been pictured as a detached and rarefied creature, it is perfectly possible for him to be politically engaged – as Marcel Proust was in the stand he took on the great fin de siècle political scandal in France, the Dreyfus case. The fan, as I shall suggest later, is wholly committed to an emotional engagement with culture, but that does not mean that s/he is uncritical or apolitical.

The aesthete has come to be associated primarily with the Aesthetic Movement of the 1870s to 1890s in Britain and also in France, where the movement, significantly, was known as the Décadence. Fatally associated in Britain with Oscar Wilde, the denunciations of its opponents were essentially against its morals, not its taste.

The movement arose as a critique of and protest against what artists and connoisseurs felt was the ugliness of much of Victorian life: its social system and its culture. They objected to the way in which the wealth of the society they lived in was built on the exploitation of the poor, who were condemned to lead lives of bitter want in hideous and unhealthy surroundings. It was not even as if the consumer products of this wealth were beautiful or even sometimes useful; the aesthetes rejected Victorian bourgeois taste as much as their Gradgrind hard-heartedness and economic utilitarianism.6

The Grosvenor Galleries in London became a rallying point. Painting and poetry were at the forefront of the movement, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, for example, expressing its ideals both on his canvases and in his verse – but its social dimension meant that aesthetic values were particularly expressed in the domestic interior and in dress. The beautiful aesthetic interior was lighter and simpler than the conventional Victorian drawing room, but it was not simply a question of decoration. The styles developed by the aesthetic movement exemplified an ideal of appropriateness and the relationship of form to function as well as the cult of beauty. The aesthetes did not merely swoon over the beauty of a flower or a vase; they desired that their ideals for an appropriate way of life be extended to all members of society.

Aesthetic clothing also played a central role: beautiful garments following the form of the body without the distortions and exaggerations of Victorian female fashion and made from materials in soft, ‘indescribable’ colours. Male followers of the movement equally rejected the utilitarian garments of their peers, opting for more picturesque styles and in particular breeches, which showed the form of the male leg.

All aspects of the aesthetic movement were savagely satirised. The Victorian poet Robert Buchanan penned an outright attack on what he called The Fleshly School of Poetry as early as 1872, but although his wrath focused on the poetry of Rossetti, he effectively denounced the whole of the aesthetic movement; and, slim as his volume is, it contains only a single idea: the aesthetic movement is pornography.

George du Maurier’s cartoons in Punch and in the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, Patience, first performed in 1881, weighed in. These satires expressed a real fear of the sexual radicalism that the aesthetic movement was also suspected of expressing. Rebecca Mitchell has shown how in Punch caricatures the aesthetic woman not only defied the conventional prettiness of the Victorian woman, but was also portrayed as hysterical and a bad mother who had, moreover, abandoned her role as ‘angel in the house’ – paradoxically, given that the aesthetes were so anxious to design and promote harmonious interiors. But Punch versions of the aesthetic woman show her as scrawny and almost diseased, with dangerous feminist and perhaps immoral intentions.7

Male aesthetes on the other hand were shown as effete. The hints of homosexuality came luridly into the light of day with the Oscar Wilde trials, aestheticism fatally tainted by the fear of the sexual deviant, the absolute opposite of the Victorian and Edwardian muscular Christian. So aestheticism challenged established and conventional beliefs in the stability and above all the social and moral necessity of traditional gender roles.

Walter Pater’s The Renaissance, published in 1873, is the clearest statement of radical aestheticism. The aesthetes’ slogan of ‘art for art’s sake’ had been interpreted as a demonstration of a lack of purpose and meaning in their work, an absence of a moral centre. This is not so surprising when you read Pater, who announced that ‘to burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life’, and who seems to advocate the cultivation of sensations and new experiences at all costs. His famous description of the Mona Lisa smile attributes to it something sinister and definitely decadent; he even claimed that ‘like the vampire she has been dead many times and learned the secrets of the grave’, and saw in her enigmatic expression ‘the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias’.8

Pater’s overripe rhetoric has tended to win out over the radical dimension of aestheticism, while William Morris’ sincere commitment to socialism tends to be questioned in light of the fact that his enterprise, designing and producing aesthetic wallpapers and fabrics, became a massive commercial success with the Victorian bourgeoisie he despised. In fact, the political right quite often has had less difficulty with the aesthetic than the left, always bedevilled by another either/or question: whether art should be subordinated to politics, or whether politics should have a duty in regard to art whether art, if it is to be considered ‘good’, must always purvey a progressive message, or whether the artist’s first duty is to be true to his or her vision.

The following essays discuss the aesthetic dimension of a range of cultural experiences and practices and in particular their emotional significance for participants. The anthropologist Georges Devereux once wrote that all academic research is a form of autobiography and has roots in the personal, and it is obvious to supervisors that doctoral students (at least in the humanities) usually have an emotional investment in the subject of their PhDs. Enjoyment of all cultural works – from Agatha Christie to Schoenberg – is emotional. Cultural criticism may lay claim to detachment, but it is emotion that draws the audience to follow a star or ‘devour’ the work of a favourite author: love – actually. Yet this does not conflict with the impulse to analyse and to judge. The two are mutually reinforcing, not opposed. The cultural experiences I discuss are freighted with autobiographical memories and connections, and a significant, even if minor, part of the friction of excitement and engagement aroused by attending a concert or exhibition, is – of course – that connection between art and life.

I once dreamt that I was in the music wing of my former school. Traversing a corridor and descending a short flight of steps, I found a door I had never before noticed, painted white, unlike the wooden doors of the corridor through which I had just passed. Through this door there was, I realised, another whole wing of the building, which I had never known existed.

At the time I interpreted this dream as a representation of my thwarted relationship with my mother, who had recently died. ‘In my house are many mansions’ and those mansions, those rooms, that could never now be explored, represented what might have been and could not now be.

But the house with many mansions stands also for the diversity of cultural experience. To classify culture as ‘high’ or ‘low’, ‘populist’ or ‘elitist’ is to cut off possibilities, to not open the door into the unexplored rooms. Elitists and populists alike graft their political prejudices onto aesthetic works and events. On the other hand, what cultural criticism has taught us is that each work, each event does carry a political, an ideological and moral meaning. There is no such thing as ‘just entertainment’.