Chapter 2

The Three Assumptions

One morning several years ago I sat down with my laptop to begin writing my first book: a workbook for teens with social anxiety. I’d never attempted to write anything of this scale before and I could hardly believe I was doing it. As a therapist I talked about anxiety every day with my clients, but writing about it was a different matter.

As I reached for the keyboard my heart began to race and my stomach clenched up. I’m not really sure how to say what I want to say, I thought to myself, adding, and an author should be. Looking at my fingers hovering above the keyboard, I noticed that my nails needed filing.

What if my premise isn’t fully formed yet? I continued. What if my conceptualization is unsuitable for a book, or worse yet, just plain wrong? If I am wrong the whole world will know that I am a fraud! I suddenly remembered an article I had meant to read. Would a bit more research give me some clarity?

If this book isn’t good I’ll disappoint my editor, my readers, and my friends and family. I’ll let everybody down! I thought. At this point my hands were visibly trembling. Looking out the window I noticed that someone really should pick up that dog poop in the backyard.

None of the tasks that were calling me away from my laptop were truly important or time sensitive. What made them suddenly compelling was that both my body and my brain were telling me that something was wrong. I was experiencing the very thing I considered myself an expert on: anxiety. I was hijacked.

If we examine my anxious thoughts that morning, we can recognize three assumptions I had made. First, I thought I had to be certain about what I was going to write. Second, I thought that if I got anything wrong I would be exposed as a fraud. Third, I thought if the book wasn’t successful I would disappoint everyone.

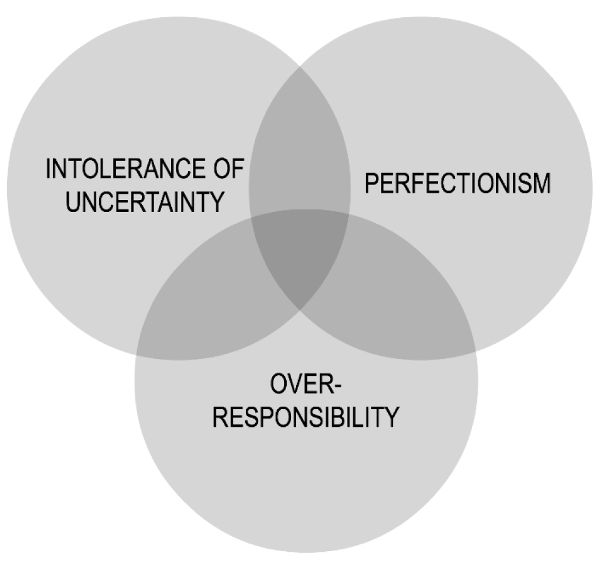

These three assumptions are universally shared by all anxious people. (Yes, reader, as you know if you read the introduction, I am one of you!) Because they echo the survival agenda of the monkey mind, I call them collectively the monkey mind-set.

- Intolerance of uncertainty: I must be 100% certain.

- Perfectionism: I must not make mistakes.

- Over-responsibility: I am responsible for everyone’s happiness and safety.

These assumptions are impossible standards. The more we attempt to live by them, the more anxious we will be, and the less likely we will be to take the risks that are necessary to take in order to live freely and follow our dreams.

That morning in the backyard, I stopped and took a look at myself. To write this book is my heart’s desire, I thought. Why am I holding a pooper scooper instead? The monkey mind-set seldom takes us anywhere we want to go. In fact, it almost always holds us back from what we long for in life.

You will recognize at least one, if not all three of these assumptions, as a central pillar of your own belief system. The first is particularly widespread. In fact, you can’t be anxious without it!

Intolerance of Uncertainty

The ability to plan for the future—to anticipate problems and opportunities—is one of the most important, if not the most important, adaptations of our Homo sapiens brains. Whether the issue is our health, our finances, or our family, we like to know what lies ahead. What if I get sick? Will the market crash? Will my loved ones arrive safely? These are our constant concerns, and we plan with them in mind. But when does reasonable planning turn into worry and obsession?

Your monkey’s central mission—keeping you alive and safe within your tribe—is best accomplished by eliminating all uncertainty. The monkey motto is What you don’t know might kill you. From its perspective, the only time it’s safe for you to relax is when you can anticipate and control every outcome. Be certain or die!

Yet the only thing we know for certain is that the sun will come up tomorrow. If we cannot tolerate not knowing what will unfold in that morning light, we won’t be able to sleep. Until we’ve eliminated every threat, we will be unable to relax or feel any pleasure. We’ll agonize over decisions because we think that with enough research and caution we can always make the right choice. Presented with something new, we’ll assume it is dangerous unless it’s proven to be safe. We’re always preparing for the worst because the worst is probably just around the corner.

This mind-set takes its toll. Constant hypervigilance keeps us worried and stressed—especially problematic at night when we are trying to sleep. Making decisions is difficult because we believe we need to be sure we are making the right one. Big decisions like choosing a college or a job are paralyzing. Even something as simple as choosing a pair of shoes can become a labyrinth of pros and cons.

Difficulty tolerating doubt can lead to compulsive checking behaviors like making sure doors are locked and appliances are turned off. You’ll tend to overplan things; even weekends and vacations have a to-do list. And when the list doesn’t get finished or things don’t go as you planned them, you become upset and have difficulty enjoying the moment.

The problem with needing to be certain is there’s a never diminishing supply of things to make certain of. Every waking minute you’ll be striving for that which is unattainable: complete certainty about all things. When your default protocol is to guarantee a good outcome in every situation, you wind up treating life itself as a threat—something to be checked on, analyzed, evaluated, controlled, and conquered. Instead of living fully and dealing with whatever may go wrong, you spend your precious days on earth worrying about what might happen.

Maria

Let me introduce a composite client of mine with this monkey mind-set. Maria’s presenting problem was her sensitivity to physical sensations, typically a sudden stabbing pain in her heart area, pressure in her head, flashes of light in her eyes, or tingling in her extremities. When she had one of these sensations, she worried that it might be a sign something was wrong, like a heart attack, a brain tumor, a detached retina, or a nervous system disorder. To ease her anxiety, she monitored the symptoms closely and looked them up on the Internet. Her doctor reassured her that they were harmless, and her tests showed that she was healthy, but Maria was spending more and more time and energy dealing with these sensations and she felt they were ruining her life. “I knew the pain I was having was probably harmless,” she told me after a trip to the ER, “but what if it was an aneurysm?”

Although Maria was smart enough to recognize that random sensations are seldom pathological, her assumption was, I must be certain. Every sensation was guilty until proven innocent, and the cost of investigating them was wearing Maria down. Maria was hijacked, acting out of an intolerance of uncertainty.

Nearly every anxiety sufferer I have met shares Maria’s mind-set: this assumption that certainty is not only possible, but necessary for our peace and happiness. The truth is just the opposite. No amount of preparedness can control every outcome. Life always provides adversity, for which we need flexibility and resilience. And life also provides pleasant surprises—joyous and peaceful moments that we can’t anticipate. These are wasted, sadly, on those of us who are only open to what we can be certain about.

Some of the problems that those of us with a need to be certain have are: difficulty relaxing; difficulty making decisions; difficulty forming opinions; worrying about health, family, and finances; overplanning and getting upset when things don’t go as planned; inflexibility; obsessive-compulsive tendencies; and being overcontrolling.

To assess how active this mind-set is for you, download the Intolerance of Uncertainty quiz at http://www.newharbinger.com/35067.

Perfectionism

Many of us like to think we have high standards. We don’t settle for ordinary; we aim for the stars. We expect the best for, and of, ourselves. This is the popular conception of perfectionist thinking.

Alas, true perfectionists rarely feel this way. With the perfectionist monkey mind-set, you have to hit what you are aiming at. There is no room for error. Anything less than a perfect outcome means failure.

While others find motivation from challenge, a higher purpose, a promised prize, or simply the joy of doing the thing itself, if you are a perfectionist your motivation is a fear of failing. Your mantra is, Don’t screw it up! Only when you’ve completed the social interaction or task without making any mistakes will you be able to relax.

This mind-set is often triggered when the perception of threat is centered on your status within your tribe. If the outcome of a situation could result in you being judged negatively by your family, friends, peers, or superiors, your monkey mind will sound the alarm. To the monkey, losing status could mean fewer allies, less money, fewer choices for a mate, even total rejection—all potentially serious threats to your survival.

When we are hijacked with anxiety we tend to think with the monkey. We overestimate the threat and underestimate our ability to cope with whatever rejection may result if the threat were to manifest. As a result, our daily agenda consists of a hundred little failings that need to be prevented. In social situations we must not get a fact wrong in a conversation, or worse, have nothing intelligent or funny to say. We dare not arrive late, dress incorrectly, or forget to use mouthwash. We must never make a fool of ourselves or be criticized for our behavior. We wonder, Did I make a good impression? Our social life is like a house of cards—one sneeze and everything tumbles down.

The perfectionist strives to be the best, thinking that when you are the best nobody can criticize you. But since there is always someone who is better, or threatening to become better, you’ll always have something to prove. So you compare yourself to others, hoping to find that you are as good or better.

More often you come up short. Perfect is pretty hard to pull off. The result is that you feel like an impostor and you work harder so that no one will suspect it. You put in extra hours at work yet never quite feel secure. The perfectionist can’t seem to hit the sweet spot where she just fits in.

Yet our culture glorifies perfection. Successful business leaders are often self-proclaimed perfectionists, treating the label as a badge of honor. The great artist, musician, or sports hero’s “quest for perfection” sounds noble, but in fact, relatively few high achievers expect perfection from themselves. They may aim for the stars, but they are comfortable coming up short and don’t let it stop them from trying again.

By contrast, perfectionists often hedge their bets, only doing things they know they’ll be good at. You’ll take the assignment if it plays to your strengths. You’ll join the team so long as you’ll be the best at your position. If you do get saddled with something you aren’t good at, you may just put it off until the last minute, where you’ll have an excuse—not enough time—to be less than perfect.

Since the perfectionist can’t make mistakes, you need to play it safe. You’ll set a goal so long as the steps to get there are clear. You’ll avoid tasks that are outside your experience or that will tax your skill set. You’ll avoid problems that require creativity because creativity requires experimentation and failed attempts.

Yet failure is always looming. There is risk involved in every decision or action we take. When we allow for some risk we give ourselves more choices and we prepare ourselves for when things go wrong. If we deny ourselves the privilege of being wrong or failing, we’ll be unable to take the risks that are necessary for meeting our personal goals. This is why, in addition to anxiety, perfectionism is associated with depression, procrastination, addiction, and low self-esteem.

Eric

Eric—like Maria, a composite case—came to me with two problems. He was having difficulty making important decisions at work, and as a result was falling behind despite spending sixty hours a week there. In his dwindling free time he was, as he put it, “holing up at home” instead of going out to meet people. Things culminated when he was so ashamed of his recent job performance, and so afraid of “blowing it by saying something dumb,” that he skipped his annual office holiday party despite the fact that he was one of the company’s founders.

It wasn’t difficult to see the common thread in both of Eric’s problems. While he professed to love his IT management job, he’d turned it into a performance for others. Everyone at work, from his partners right down to the file clerk, was in the audience watching him standing in a bright spotlight on the stage. One mistake and their reviews would close the show.

Socially he was performing too. Eric was overweight, and he felt unattractive. He believed he wasn’t good at small talk and every word that came out of his mouth felt false. People around him seemed so relaxed and natural with each other. Eric felt like an actor without a script, improvising to a tough crowd. He was sure they were judging him harshly.

Eric was on a treadwheel. He believed he needed to prove himself every minute of the day. He judged any mistakes he made, and any judgment or criticism he received, to mean that he was not good enough or he had failed in some way. In Eric’s mind, his shortcomings made him less worthy as a human being, a candidate for rejection by those he loved and depended on. He believed that as long as he turned the perfectionist treadwheel, he could keep that from happening. If you share the perfectionist mind-set, you have your own treadwheel. There are endless threats to your status, every one of them a problem for you to fix.

Some of the problems those of us with the perfectionist mind-set have are overworking, underachieving (due to not trying things you are not good at), believing if people saw the real you they would think you are a fraud (Impostor syndrome), rumination over past mistakes, low self-esteem, procrastination, difficulty making decisions and being overly conservative in choices you do make, rumination over social interactions, shyness, and a tendency to hold back for fear of making a fool of yourself or being judged harshly by others. You can take a quiz to help evaluate your own tendency toward a Perfectionist mind-set at http://www.newharbinger.com/35067.

Over-responsibility

One of the best compliments anyone can give you is that you are a responsible person. At home, responsible people support their loved ones both emotionally and financially, building strong families. At work, responsible people look at their own weaknesses and mistakes, and instead of making excuses, learn from them to develop new skills and strengths, and get promoted. In society, responsibility is what allows us to strive for a more equal and just world. Responsibility leads us to care about poverty and pollution. Taking responsibility means not making things worse, and taking actions to solve problems.

So what’s the problem with a little over-responsibility? Can you have too much of a good thing? Oh, can we ever!

My daughter Rose has always been disorganized and forgetful. When she was growing up, mornings were her worst time. She would get up a half hour before the bus, eat a leisurely breakfast, then rush around at the last minute getting ready for school. Naturally she forgot things like her coat, her lunch, or her homework, and I made myself crazy trying to “help” her. I pushed, I reminded, I scolded. Worst of all, when I got the inevitable call from her that she had left an important assignment at home and needed it desperately or else she would get a failing grade, I drove it to school!

To some this may look like good parenting. When we love someone, we should protect her from bad things happening, shouldn’t we? That’s the cultural assumption we share, but the truth was that for Rose to ever understand her own responsibilities and what she’d need to do to survive and thrive, she would have to suffer the consequences of her own actions. She’d have to get an “F,” possibly even flunk the course. That was the only way she would learn, but I was too over-responsible to allow her do it.

Under the guise of being responsible for my daughter, I was being irresponsible to myself. Thinking we are capable of changing others or keeping them happy leads to burnout, both personal and professional.

Are you a “people pleaser” who can’t say no and can’t set limits? Are you always staying late to wrap things up or arriving early to set things up? Are you the “volunteer” who’s left standing alone when everybody else takes a step back? Have you “got people’s back” even if it means doing more than your fair share? Can others count on you to never let them down? And how about family gatherings? Are you the “good hostess,” worried about everyone having a good time? I certainly know that one!

Over-responsible folks are afraid of losing connection. We direct our responsibility toward those we feel we cannot risk displeasing—the boss, coworkers, friends and relatives, and even in some cases, complete strangers. In the process we neglect ourselves.

Perhaps you’ve been aware that you are doing too much and tried to set limits with others. If they seem disappointed, do you feel guilty or selfish for your assertiveness? If others get upset with you, do you think it’s your fault that they feel this way? Even when others are upset about something you had nothing to do with, with an over-responsible mind-set you think it’s your job to do something about it. The over-responsible mind-set calls for bending over backward to accommodate others’ needs and expectations, whatever it takes to preserve the connection.

This isn’t to say that we all don’t share certain responsibilities. The environment, world hunger, and wars are good examples of real threats against human health and safety, and every individual plays a part in resolving these problems. But if you cannot rest until the world is well fed, every country is at peace, and the environment is safe, you’re thinking over-responsibly.

Where over-responsibility becomes the biggest burden and the most difficult to recognize is when the perceived threat is to others’ well-being and safety. We are taught to care, to lend a hand when needed, to look out for one another. When someone you care about is making a poor choice, do you think it is wise for you to set him straight, to point out what he can do instead? When someone you love is in pain, do you believe you cannot feel better until she does?

Samantha

Over-responsible people have difficulty recognizing what is within their control and what is not. Even when you have a strong personal stake in a conflict, if a solution is beyond your control, it is not your responsibility. By way of example, consider Samantha, a composite client of mine, whose thirty-year-old son, who had an alcohol problem, was causing her great distress. For ten years before she came to see me she whittled away at her savings and neglected her own health trying to save him from his addiction, doing everything from paying his overdue rent to pushing him into rehab. Samantha didn’t think she had any choice. Her son was a binge drinker, and he could easily pass out and hurt himself, or he could lose his job and wind up on the street.

She thought:

- As long as my son in pain, I need to do something to fix his problem.

- My son’s needs are more important than mine.

- If I set a limit with my son and he becomes upset, it is my fault.

- If something bad happens to my son and I could have stopped it somehow, it will be my fault.

Thinking that the only way you’ll be happy and safe is if others are happy and safe burdens you with infinite tasks and problems—too much responsibility for anyone to handle. While you can try to make others happy and you can try to keep them safe, you cannot change them. They will continue to rely on you as long as you keep it up. Bottom line: if taking care of your own needs is a casualty of taking care of others, you’re being over-responsible.

Problems that arise from the over-responsible mind-set include: working harder than others, taking on other people’s problems, poor self-care, burnout, constant worry and rumination about others, giving advice to others to the point of pushing them away, blaming yourself for things that are not your fault, difficulty setting limits, and difficulty with asserting yourself. To help you recognize this mind-set in your own life take the Over-responsibility quiz at http://www.newharbinger.com/35067.

These are the three false assumptions of the monkey mind-set. As long as I am certain, as long as I am perfect, and as long as others are okay I will be safe, able to relax, and happy. Each of these assumptions overestimates the threat and underestimates our ability to cope. Each of them treats the perception of threat as accurate, a problem to be fixed.

Whether you are overly anxious or suffering from an anxiety disorder, you will recognize at least one in your own thinking. You may have a combination of a need for certainty and perfectionist thinking, or like me, a combination of all three.

Because this mind-set is always present when we are anxious, it is tempting to think that it is the cause of all our anxieties. Most therapy and self-help is based on the premise that changing how we think will change everything. As any scientist will tell you, however, there is a big difference between association and causation.

I view the relationship between the monkey mind-set and our anxiety as more of a chicken-and-egg conundrum. What matters, and what the next chapter will address, is not which came first—the mind-set or the anxiety—but what is maintaining them both. Here’s a hint: The very things you are doing to control your anxiety are feeding the monkey!