Chapter 3

Feeding the Monkey

Remember in chapter 1 how I used the expression “leaping into thin air” to describe our reaction to anxiety? I was hardly exaggerating. Whether it is literally leaping out of the way of a speeding truck, or merely postponing an important decision, you are acting with abandon, without regard for later consequences. Whether calling your doctor about a new spot on your arm or calling your son to make certain he’s sober, you are acting to keep yourself or a loved one safe now. The things we do reflexively in order to avoid, resist, or distract ourselves from negative feelings are what I call safety strategies.

When I chose to do more research, file my nails, and clean up after the dog instead of writing my book, I was performing safety strategies. These were behaviors that would keep me safe from the perceived primordial threats: loss of social status and being kicked out of the tribe.

I wasn’t thinking all this through, of course. In a hijacked state of mind, self-awareness is difficult if not impossible. We employ safety strategies unconsciously, in response to anxiety—the monkey mind’s call to action. Something is wrong. Do something! And when we do something the monkey rewards us. It takes its finger off the anxiety button and we feel relief. When I closed the laptop lid and stood up I immediately felt better. My stomach relaxed and my heart rate returned to normal. I was no longer anxious and I was still getting stuff done. After a little rest I could return to my writing for a fresh start and everything would be better, right?

Wrong! The monkey mind wasn’t only watching my thoughts for signs of threat, it was also watching my behavior. When I closed the lid of my laptop I sent a message to my monkey. The message was, Good call! Writing is dangerous to my survival.

I confirmed the threat. I agreed with my monkey that writing the book at that point was an activity to be avoided. The monkey mind likes confirmations. As I pointed out in chapter 2, it isn’t good at risk assessment, and generally relies on wild guesses. My confirmation of the threat was a reward. I was feeding the monkey.

You can guess what the monkey did later that morning when I sat down again to write. I got hammered again with a tsunami of anxious thoughts and feelings. My safety strategy was maintaining a cycle of anxiety. Every time I fed the monkey, with every repetition of the cycle, in exchange for a temporary relief from anxiety, I guaranteed myself more anxiety in the future.

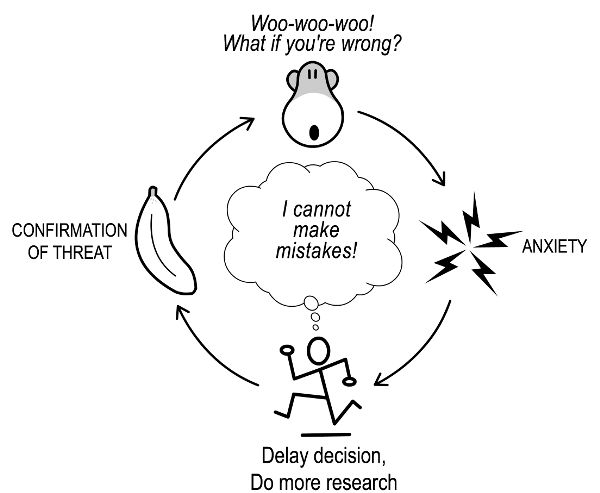

Here’s what the anxiety cycle looks like.

When dealing with speeding trucks, rattlesnakes, and bears, an anxiety cycle is a good thing to feed, but most situations we face on a daily basis are more ambiguous. Was there a real threat that I could lose status with my friends, family, and fellow professionals by writing a lousy book?

Possibly. But when calculating how much of a threat it may be, the monkey has a problem. Estimating odds and making risk assessments are done elsewhere in the brain. The monkey doesn’t do math.

It can only guess. As it does so often for the anxious person, it guesses on the side of safety. And why should it change its guess after my behavior just confirmed it?

The monkey mind is like a small child or a pet watching you for guidance. I emphasize the word “watch.” You cannot tell this part of your brain anything. The monkey can’t be reasoned with, comforted, or distracted from its mission. The only way we can get what we want in life is to override its warnings with our behavior.

In my case it would mean continuing to write despite the anxiety I was feeling. If I were able to do that long enough, over time the monkey would get the message that I can handle writing a book, and tolerate the risk involved. Yet how could I do that when I was operating with a monkey mind-set, when I shared the same perception of the “threat”?

The monkey mind-set will have to be overridden, temporarily at least, before any change of strategy can be employed. And unfortunately, every time we use a safety strategy we reinforce the monkey mind-set too.

Feeding the Mind-set

Remember how as a child you used to cross your fingers in hopes that your parents would stop for ice cream? If they didn’t stop you’d forget about it, but if they did stop, you concluded, Because I crossed my fingers, we’re having ice cream! Or perhaps you remember feeling responsible for something you didn’t actually cause, like Because I disobeyed my mother she got a stomach flu.

In an anxious, hijacked state of mind our thinking becomes childlike and superstitious. We attribute all outcomes to our own behavior. If you perform a safety strategy and happen to end up safe, unconsciously you conclude, Because I took precautions I am safe! I call this monkey logic.

Monkey logic works great when there is a real threat to your safety. But when there is a misperception of threat, it merely supports your monkey mind-set. When I closed my laptop that morning, I reconfirmed the assumptions of my monkey mind-set: I must be certain! I cannot make mistakes! I’m responsible for everybody! When we feed the monkey, we feed the monkey mind-set.

So long as I clung to my monkey mind-set and used safety strategies I was safe—safe from being wrong, from failing and letting everyone down. I was preventing the worst—losing social status—from happening. But in doing so, I was also preventing the best thing I could imagine from happening: writing my book.

When clients come to see me they too are missing out on their best. Let’s take a closer look at the anxiety cycles that keep them anxious and stuck in a monkey mind-set.

Maria’s Intolerance of Uncertainty

Maria, who worried that her physical sensitivities signaled serious illness, was not particularly active, and her sedentary lifestyle made her prone to more than her share of the usual aches and pains. Chest pain in particular triggered a perception of threat. Thinking she was having a heart attack, she made numerous trips to her doctor and the ER, only to find that she had pulled a muscle on her rib cage, or that she had a cramp that disappeared on its own.

No matter how many times this pattern repeated, Maria’s anxiety only worsened. It seemed to her that her body was a battlefield, a highly uncomfortable place to be. Maria’s monkey was working overtime alerting her to threats to her safety. What was feeding the frenzy was Maria’s reaction to the anxiety alarm. Every time Maria took steps to be certain she was safe, she confirmed the threat, awarding her monkey mind a nice ripe banana. With impeccable monkey logic, it deduced, Because I alerted Maria to the possibility of a heart attack, she went to the doctor and prevented it!

Maria’s cycle of anxiety was completed and ready to roll again. Here’s what it looked like:

Maria, of course, was not only feeding her monkey. She was thinking with it. Monkey logic dictated, Because I went to the emergency room and confirmed that my heart is okay, it is okay. Each turn of her anxiety cycle reinforced the I must be certain assumption of the monkey mind-set.

Maria thought she needed certainty about her physical symptoms. What do you think you need to be certain about?

Eric’s Perfectionism

Eric’s anxiety was triggered by doubts about whether he was good enough to be accepted by others. Since he thought he needed to be perfect in order to be accepted at his management job, as well as socially, he had plenty of doubts. A great example was the time he had to make a decision about which vendor to contract with for a major software upgrade for his office. While they all promised to make things more efficient, there would be a potentially difficult transition period where everyone would have to learn whatever system he picked. To Eric, making the right choice was essential for maintaining his status in the company. To his monkey mind the decision was a primordial threat. If he were to pick a solution with a difficult learning curve, or one that didn’t work as well as everyone hoped, he would be judged a failure and in effect, be kicked out of the tribe.

Eric managed his anxiety by working overtime researching the options. He interviewed reps from the various vendors extensively, compiled notes, and made multiple projections. After months of working overtime and fielding questions from his increasingly impatient team, he was still no closer to committing.

Eric was in a cycle of anxiety. Every time the subject of the software decision came up his monkey mind flagged it as a threat and turned on the anxiety alarm. You must get this right. Do something! Instead of making the decision, Eric made another phone call to one of the reps, or did some more research, or made another pros and cons list. When he engaged in these safety strategies, his anxiety went down and, for the moment anyway, the crisis was abated.

Eric’s safety strategies were keeping him not only from making a less-than-perfect choice, but from making any choice. Every time he delayed a decision in response to the monkey’s alarm, he fed the monkey. Confirming the perception of threat around decision making programmed his monkey for more anxiety alarms in the future.

Every monkey feeding also fed Eric’s perfectionist mind-set. Monkey logic dictated, Because I delayed the decision, I did not make a mistake and am safe.

Here is Eric’s anxiety cycle in a diagram:

Samantha’s Over-responsibility

For Samantha, mother of an alcoholic son, the cycle of anxiety was gut-wrenching. As I noted before, the perceived threat was real. Her only son was in jeopardy of losing his job, his home, his life, and there isn’t a parent on earth who wouldn’t feel anxious about that. But Samantha was depleting her savings trying to cover for his expenses and paying for his unsuccessful rehabs. She had high blood pressure and she wasn’t sleeping well. Her doctor told her she needed to take better care of herself or she wouldn’t be of much use to anybody. The question was, thirty years after the birth of her son, how was Samantha maintaining such a high level of maternal anxiety?

To answer that, let’s start with the most common threat perception in Samantha’s daily life. When she hadn’t heard from her son in a while, images often popped into her head—horror scenes like her son passed out on the floor with blood flowing out of his ear. These images are normal, perfectly harmless, and no indication that the threat is any more imminent than it was before she had the image. But when the monkey sees these images it sounds the alarm, sending Samantha into a painful state of apprehension. She’s immediately hijacked. What if he is passed out and needs medical attention? If I don’t do something he could die.

What Samantha does next is automatic. She calls him to check on him. If she hears his voice, she’ll know he’s okay and she can stop feeling this way. This is Samantha’s safety strategy. She’s keeping her son safe, and as soon as she hears his voice—even though he sounds irritated and is short with her—she feels she can breathe again. The crisis is canceled—or rather, postponed.

By calling her son for confirmation that he is alive and well, Samantha is telling her monkey that the threat perception is real, that her son could indeed have been passed out and bleeding. In effect she told her monkey, Thanks for the heads up! Making me anxious really got my attention and saved my son. Be sure to do the same thing next time I get a thought like that!

Here it is all in one picture.

Feeding her monkey fueled the cycle and each turn not only reinforced the perception of threat, but also reinforced her monkey mind-set. Her monkey logic said Because I called my son, he is alive, supporting her monkey’s belief that she was responsible for keeping him alive.

Can you identify an anxiety cycle of your own? It’s a powerful exercise to visualize any cycle you are trapped in. First, download a blank Anxiety Cycle chart like the one below at http://www.newharbinger.com/35067.

Begin by thinking of a situation that makes you anxious. It could be a physical sensation like in the case of Maria, or it may be a situation that happens at work, or it may be related to your home life and family. Once you have a situation in mind, ask yourself these three questions:

- What am I afraid of?

- What’s the worst thing that could happen if this comes true?

- What would this mean about me, my life, or my future?

Using the answers to these questions, determine your perception of threat.

Next, describe how these thoughts make you feel. What negative emotions and sensations can you identify? What parts of your body are affected? Make note of them in your chart.

Once you’ve got a good handle on what you’re thinking and feeling, ask yourself, What do I do to keep the worst from happening? This behavior is your safety strategy. When you’ve written it in, the cycle is complete—almost.

When you perform your safety strategy, which monkey mind-set or combination of mind-sets is activated? Write that in the center bubble. To keep it simple you can use whichever of the three assumptions fits best with the situation: “I must be 100% certain,” “I must not make mistakes,” or “I am responsible for everyone’s happiness and safety.”

Neither Maria, Eric, nor Samantha were living the lives they wanted to live. Thinking with the monkey mind-set is like being an archer who thinks she must hit the bull’s-eye. The rest of the target counts as a miss. Only when her arrow lands dead center, within the circle of safety, will she allow herself any satisfaction, and even then only until her next “miss.” It’s an all-or-nothing mentality, and we usually wind up with nothing.

The Downward Cycle

Safety strategies and their monkey mind-sets are aimed at eliminating risk. Yet without some risk, new experiences and learning are impossible. Our thoughts, our behavior, and our level of anxiety become rigid and predictable. Over time, the heart’s desires are forgotten. Eric dreaded going to work at the company he himself had founded. Marie gave up the thing she loved the most—travel—because she didn’t dare stray from her hospital. Samantha would never be able to retire because her responsibility to her son was draining both her bank account and her health. Within the cycle of anxiety, the joy of being alive is lost. Our world gets smaller and smaller.

“Doesn’t the monkey mind realize there is more to life than just surviving?” you may ask. “Can it be so primitive and stupid that it doesn’t get what’s important to me? Can’t it learn anything? Can’t it see what I want for myself and just turn the anxiety down a notch so I can get it?”

No, it can’t. Reasoning with the monkey mind is impossible. It’s too simple and too primitive to see the big picture that you can see with the rest of your brain. The monkey has a narrow little view of the world. Its perception of what is a threat and what isn’t can only be altered by one thing. It learns by watching what you do. If you want to stop being ruled by the monkey, you are the one who will have to change.

This is my promise to you: Once you learn how to respond to anxiety wisely, rather than reacting to it, not only will you become resilient to anxiety but infinite possibilities will open up for you. New experiences and learning will expand your world and enrich your life beyond what you can now imagine.

Before you can change anything, however, you’ll need to be very aware of what you’re doing now. In the next chapter we’ll learn how to identify the strategies you’re presently using to avoid negative feelings and stay safe.