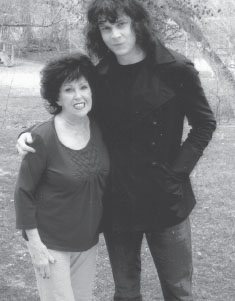

With my buddy, Jack White.

After my disastrous experience at the Grand Ole Opry in 1955, I vowed I would never go back again. But you can’t stay mad forever. In January of 2011, I finally returned to the Opry stage for the first time in 56 years. The show had moved from the Ryman Auditorium to a much larger venue on the outskirts of Nashville in the mid-1970s, but in recent years they’ve started going back to the Ryman in the winter months when there are fewer tourists in town. Since it was the off-season, I got to return to the exact stage where I’d been before. This time it was a wonderful experience. I even wore a white fringed blouse with long sleeves, so the ghost of Ernest Tubb wouldn’t have to worry about seeing my shoulders. It’s not that I learned my lesson, it’s just that old age got me! I always say that neck lines go up when you’re a little girl, come down when you’re a teenager, and go right back up if you become a gospel singer. Now I can wear whatever I want, but you have to ask yourself what looks best for where you are in life.

The man who coaxed me back to the Opry stage was singer, guitarist, and producer Jack White. I had just finished recording my fortieth studio album, The Party Ain’t Over, with Jack, and he suggested we go to the Opry with the band he put together for our tour. It was actually the first time he and I performed together publicly, and I’ll never forget what a great evening it was.

When we were onstage Jack told the audience the story of what had happened to me the last time I was at the Opry. He went into details about how I got in trouble for wearing something too revealing and how I’d been sent back to my dressing room to cover up. He changed the last part of the story and said I finally came strutting out onstage naked, and that’s the day that country music embraced the “Nudie suit.” I didn’t know he was going to say that, but I thought it was pretty funny. The audience whooped and hollered and got a big kick out of it.

I was only vaguely aware of Jack before we worked on that album together. I’d heard his name once when I was over in Europe, and I knew he’d had a band called The White Stripes. But I didn’t really know much about who he was. I always try to say I knew of him more than I actually did, because Jack’s a big star, and I don’t want people to think I’m not keeping up! But if I didn’t know much about him at first, I found out real quick.

The idea of working with Jack came to me through Jon Hensley, who was my publicist and manager until he died unexpectedly at the age of thirty-one in 2015. Jon was really great about making sure younger folks knew who I was and appreciated my music. One day he mentioned to Wendell that Jack White was interested in recording me. Wendell didn’t know anything about Jack at the time, so he didn’t pay much attention. We were at home one day when he said, “Boy, I keep getting all these emails from this Jack White guy. He must really want to work with you.” My daughter Gina was walking through the room and overheard his comment. She stopped right in her tracks. “What did you say, Dad? Jack White is a huge star. You need to write him back immediately!”

Once the grandkids found out about it they went nuts. My granddaughter said, “Ma! You don’t know Jack White? He’s the biggest thing in the world. You’ve GOT to work with him!” At first I wasn’t really sure if I wanted to do it or not. Honestly, I was a little intimidated. Jack was a big rock star, and he seemed to come from a different world than me. I didn’t know if we would be particularly compatible or if he would really understand me as an artist. But for the sake of my children and grandchildren, I reluctantly resigned myself to giving it a try.

Jack and I began communicating about song ideas over the phone and via email, but I never actually saw him in person until it was time to record. I went down to Nashville in 2010 and met up with him at his house. He had a beautiful home with about five acres. He showed me around, and I thought he was so cute with that hair hanging down in his face. I never did mind long hair on guys if it was clean and neat. There was a shyness about Jack that kind of reminded me of Elvis. I liked him right away, but there was still a bit of awkwardness between us, since we were virtually strangers.

We went into the control room in his studio, where we sat down to talk and get to know each other. He explained to me that he didn’t enjoy digital recording, but preferred to make records on analog tape the way we used to do it. He was excited to show me his vintage tape recorder. He said, “You know what I call this one?” I shook my head. He said, “Her name is Wanda.” He let out a nervous laugh and I gave him a great big smile. I was flattered by that. The more we talked the more comfortable I got. Jack is a genuine person, and I could see that this guy was really a fan. He could name a lot of my songs, including some of the lesser-known things, and was obviously very familiar with my career. I respected him because he knew my kind of music even better than I did. He had studied it. It was clear that Jack was for me in every way, and I felt honored by the respect he showed me.

After we talked for a little while, Jack said, “Are you ready to hear some of your playbacks?”

I was a little taken aback. “You’ve already got playbacks?” It never occurred to me that he might have already recorded the tracks before my arrival. I said, “Jack, you didn’t ever ask me what key I sing these songs in.”

He kind of chuckled uneasily and said, “No, I’m sorry. I kind of guessed at it.”

Once he started playing the songs I liked what I heard, but there were a couple of them I couldn’t sing. The key was too high and they were too fast. “Rip It Up?” My gosh, it was so fast! I said, “Jack we can’t use that one. I won’t be able to do it.”

“Oh, it’ll be fine,” he said. “I think you can handle it.”

“The only way I can sing it is if we lower the pitch, and the only way to lower the pitch is to slow it down. I’m going to have to slow it down anyway to get all those words in.” Once we did that, it was still on the higher end. When you hear it on the album, I sound like I’m about sixteen years old. On the next song, I sound like an old lady!

I was happy with the songs we picked out for the album. When Jack said he wanted me to do “Rum and Coca-Cola,” I couldn’t believe it. I always loved the version by the Andrews Sisters since I was a kid, and I’d always wanted to record it. I don’t know why I never had, but it was as if Jack knew exactly what was right for me. That blew my mind.

One of the songs he had pushed me to do was “You Know I’m No Good” by Amy Winehouse. Amy was still living at the time, but I wasn’t familiar with her. From the start, I told Jack I didn’t really know the song and, truth be told, I didn’t even actually try to learn it. I didn’t want to record it. I thought maybe we could skip over that one, but when I found out Jack had already brought the band in to create the track, I figured there wasn’t any getting out of it. Finally, I told myself, “Wanda, if you’re going to work with this young guy, do what he suggests. He has his finger on the pulse and he’s got your best interest at heart.”

Of course, that didn’t make me any more prepared. I was in the recording booth with headphones on. Jack would sing me the notes from the control room. He’d have me sing along with him two or three times, and then we’d go to the next line. He taught me the song right there on the spot. Jack was incredibly patient, which is unusual for a young man. What’s funny is that I didn’t want to record “You Know I’m No Good,” but it has since become one of my favorites. That’s one of the songs I regularly do on stage, and I love to sing it. I was so sad when Amy Winehouse died in 2011. She was only twenty-seven years old, and was so talented. I can only imagine how many great songs we missed out on when she left us too soon.

Jack knew that Bob Dylan liked my music, so he called Bob and told him about our session. Jack said, “I want her to do one of your songs. Which one do you think it should be?” Bob didn’t pause for a second. He replied, “Oh, ‘Thunder on the Mountain.’ No question.” Bob’s song had just come out four or five years earlier, but Jack and I both agreed it was a great song for me. The original version references Alicia Keys and her being born in Hell’s Kitchen. We changed it to Jerry Lee being born in Ferriday, Louisiana. That was a lot of fun to give a little nod to my old friend. We changed some other lines, too, to reference Oklahoma and my song “Funnel of Love,” so I like to tell people that Bob Dylan and I are co-writers. Obviously we’re not, but it sounds impressive, doesn’t it? Bob once famously called me “an atomic fireball of a lady” on his radio show, so I have to do my best to live up to his expectations!

We wound up shooting a video for “Thunder on the Mountain,” and Jack just amazed me. He’s real feisty onstage. He’s all over the place, kidding me and bumping me. I don’t know how many takes we did for that, but every single one was like the first one with Jack. He put his all into it each time. One of the things about Bob Dylan’s songs is they tend to have plenty of words in them. I hadn’t memorized “Thunder on the Mountain,” so there were cue cards everywhere on that set. The cameras were trying to keep from showing them, and I think they succeeded. The whole thing was fun and exhausting. I had a blast. Jack brought that old rock-and-roll energy back when I needed it most.

We set up a short tour with three or four shows. They were really more like record release parties, but Jack’s name on the bill drew some really big crowds. I had a nine-piece band behind me, plus two background singers, including Ashley Monroe, who has gone on to make quite a splash as a country singer herself. Jack had a horn section, and he had rehearsed that band so tightly that I didn’t have to worry about a thing.

We performed “Shakin’ All Over” on David Letterman’s show a few days after our public debut at the Grand Ole Opry. That was so much fun. When we finished, Dave himself came over and called for an encore as the credits rolled. He was really thrilled with it. The next night we did a concert in New York, before flying to Los Angeles for two consecutive shows at the El Rey Theater. The Party Ain’t Over came out the next day, and we did one more TV appearance on Conan O’Brien’s show. We played “Funnel of Love,” and then Conan interviewed me and Jack together afterward. I could tell Conan was a true fan of mine.

I remember when we were looking at photos for the album cover, the art director was making comments about how he could make some little tweaks to my appearance. He said, “Okay, I can sharpen the jaw line here,” and that kind of thing.

I turned to Jack and I said, “Please have him take out more of those wrinkles.”

“No, I don’t want that,” Jack said. “You’ve earned those wrinkles. I think you should be proud of them.”

Despite my little moment of vanity, Jack was right. I’d like to show the younger girls who do respect me that it’s all right to be old. We all have to age gracefully, so we must accept it as part of life, and just do the best we can. I see older women who, to me, are just beautiful with their silver gray hair, the way they dress nicely, and the classy way they carry themselves.

I have many warm and wonderful memories of working with Jack, but it was a bittersweet time in my life. When we were in Nashville rehearsing for our shows, I got a phone call from Gina telling me that Mother, or Bobo as we all called her, was being taken to the hospital. She had turned ninety-seven less than a month before, and it looked like she was near the end. I felt terrible to do it to Jack, but I had to leave to go home. Of course, he was gracious and promised the band would be ready.

I rushed home to be by my mom’s side. She hung on for several days, but I had to return for that Opry appearance. Gina called me at about three in the morning on the day I was to fly out to Nashville. “Mom,” she said, “Bobo’s gone.” I was devastated. Mother had been in mental decline for about five years at the time she died. In fact, she had to be confined to the lockdown area in the facility where she’d been living. Considering she never was any good at sitting still, it was no surprise that she was always trying to get out. She got her monitoring bracelet off one time and took three or four other old ladies with her. They got out to the road before someone realized they’d made a break for it. She caused all kinds of havoc at that place, but even though she’d not been herself for a while, it was still hard to accept the fact that she was gone.

I was in a complete fog when I received the news, but I had to get up and get to the airport. Oklahoma was covered in ice, so it took extra time to get there. We were late taking off, since the plane had to de-ice. It was a miserable morning, but we got to Nashville, had a chance to rehearse with Jack one more time, and then did the Opry the following night.

I headed right back to Oklahoma, where we buried Mother after a beautiful funeral at her beloved South Lindsay Baptist Church. The following day I was performing on David Letterman’s show. It was quite a whirlwind to be performing at two of the most important venues in the country with one of the best bands I’d ever played with in between losing and burying Mother. To say it was an emotional rollercoaster would be an understatement.

Even though that period of time is clouded with the memories of losing Mother, I can still say that The Party Ain’t Over is one of my best albums, and one of my personal favorites. It was a real challenge, which is one of the things I really liked about it. Instead of covering the same old ground once again, Jack pushed me into some exciting new territory and reignited my rebellious rock-and-roll soul at a time when I needed a little fire under me. Like Rosie Flores and Elvis Costello before him, Jack White has been another important champion of my career resurgence who also became a dear friend.