The classic historiographical and sociological claim about the nature of religious change amid the modernization of societies has been understood as a claim about the decline of religion—the secularization thesis. In line with recent ideas about this thesis, which query the validity of the inherent teleology of the notion and seek instead to understand religious change as being made up of lived social and spiritual processes, this chapter analyzes and assesses a range of formulations of the theory. It suggests that while classic theorists may have been presented as predicting and describing the ultimate demise of religion, an attentive reading of many of these authors’ texts identifies how religion is explicitly presented as persisting in some way. After establishing the core point, that theses of secularization have not inherently excluded the continuation of religion into the future, the chapter proposes a framework for employing a revised secularization thesis as a method in the study of contemporary religiosity, and especially those forms that are generally understood to be characteristically recent developments: flexible and individual forms in dynamic and noninstitutional contexts. In the framework of the Society’s extraordinary global reach, its accessibility to people of all faiths and across all backgrounds, and its chronological spread across the twentieth century, the letters of the Panacea Society’s healing users are a valuable resource for a study using the methodology proposed.

There is a longstanding tradition of sociological analysis and conventional wisdom that has perceived a more or less inevitable process of religious decline in modern cultures, especially in those where Christianity has been the dominant mainstream religion. The historian Hugh McLeod, for example, lists a canon of sociologists who “shared a commitment to the ‘secularization thesis’ … that the dwindling social significance of religion is an inevitable consequence of the process of social development in modern societies.”1 Anthony Carroll has observed that “secularization has been, until recently, an uncontested motif of accounts of modernity” and that “for much of the twentieth century, the theory of secularization was a cultural a priori that informed all thought about the modern world and its emergence from the medieval past.”2 Classic accounts of the dynamics implicated in secularization theory, such as Peter Berger’s Social Reality of Religion, describe “the process by which sectors of society and culture are removed from the domination of religious institutions and symbols” with a concomitant process for individual consciousnesses so that “the modern West has produced an increasing number of individuals who look upon the world and their own lives without the benefit of religious interpretations.”3 A number of contemporary scholars have found evidence to confirm the paradigm. Perhaps the strongest protagonist for secularization as a fundamental theoretical tool for the understanding of religious change presently is Steve Bruce. Bruce notes an ebb and flow of religious influence in Europe over a long period but detects decline overall and finds no historical case where there has been a “reversal of decline.”4

Despite a longstanding consensus, there is, nonetheless, evidence for Philip Gorski and Ateş Altinordu’s assertion that at present “secularization qua sociological theory” finds itself “in an increasingly defensive and even beleaguered posture.”5 While a decline in traditional religion is generally accepted as being evident, especially in western Europe, the attack on the thesis has come from a perception of vitality in new and alternative forms of religion and spirituality generally, and in more traditional forms of religion outside western Europe. In essence, a perception of the persistence of religion despite the decline of some longstanding dominant traditional forms of it has undermined the apparent validity of the secularization thesis. This can be exemplified in academics’ conclusions about religious change in three countries on the margins of or outside western Europe that form a significant part of this study: the United States, Jamaica, and Finland. Thus, R. Stephen Warner has argued that a paradigm shift has taken place in sociological ideas about secularization, and he has identified the “older paradigm” as “fac[ing] increasing interpretive difficulties and decreasing rhetorical confidence” with “inconclusive results … chronic in the field” in the face of “resurgent traditionalism, creative innovation, and all-round vitality in American religion.”6

In his study of religion amid cultural postmodernity in the United States and elsewhere, David Lyon says “religious life is not shrinking, collapsing, or evaporating, as predicted,” and he draws attention to the ways religious groups “negotiate new conduits for commitment, fresh breakwaters for belief.”7 The essence of his objection is that “much secularization theory produced earlier in the twentieth century mistook the deregulation of religion for the decline of religion.”8 In Finland, a country with a longstanding and widely affiliated national church, Jeffrey Kaplan has noted an underlying “vibrant current of mysticism, [and] a willingness to borrow foreign religious ideas.”9 And a study published by the Church Research Institute in Finland identifies that “firm attachment to Christian beliefs has declined” along with a decline in institutional religion. However, “belief ‘in some form’ of God has not declined,” and there has not been a decline “of religion per se.”10 The study suggests that “from the point of view of religious beliefs, the thesis of the decline of religion does not have full support.”11

Jamaica suggests a similar process to that evident in Finland, but with a more highly diversified ecosystem of religious forms. Thus, while Jamaica was among Caribbean countries showing “most notable declines in the dominant religion” between 1900 and 1980, indigenous groups “grew strongly” in the same time period, and the country has flourishing adherence to Rastafarianism, spiritism, and Seventh-day Adventism, alongside a plethora of new religious movements.12 Claire Taylor’s doctoral thesis on the ways Jamaican migration to Britain affected British churches observes that “the process of secularization noted in Europe in the twentieth century, has never been part of life in Jamaica.”13 Taylor also suggests that Jamaican migrants may in fact have helped to sustain religion in Britain.14 In a global perspective, and with a definition of religion wider than traditional and mainstream churches, there are numerous instances cited as counterexamples to a standard model of secularization.

Jane Shaw’s history of the Panacea Society indicates a similarly complex process of religious change within the Society itself. Shaw describes a decline in religiosity in Britain after the 1940s when “with the change in values in post-war Britain and the emergence of a different, less religiously inclined culture, the Society gradually went into decline.”15 This decline, however, is mainly associated with the Society’s members at the Bedford headquarters and with the sealed members (who seem never to have numbered many more than two thousand).16 This internal decline notwithstanding, Shaw observes that the healing, at least, continued to grow for a considerable time after the death of the original inspired leadership (Octavia died in 1934 and Emily Goodwin in 1943), and it is clear that applications continued to arrive at Bedford throughout the rest of the century. To that extent, Shaw’s book captures the multiple strands of the processes of religious change in the twentieth century identified by many scholars: a decline in the structured and hierarchical institution at the center (though, of course, rather unconventional in the Panacea Society’s case) and a continued vitality among ordinary users in its devolved and individualized locations.

In formulations of the secularization thesis, the majority of writers (whether for or against the idea of overall religious decline) agree that there are, in effect, three identifiable consumers in the economy: (1) those affiliated with institutional religion, (2) those subscribing to new or alternative religious forms, and (3) a large and indistinct atheistic or nonreligious population.17 Moreover, they consistently recognize a decline in traditional religion and the growth of new religions. For example, Harvey Cox’s account of the link between religious change and urban life describes a complex dynamic between all three groups. He refers to modern people “shedding the lifeless cuticles of the mythical and ontological periods” and in fact becoming attuned to “hear[ing] certain notes in the biblical message that [they] missed before.”18 Paul Heelas and Linda Woodhead assess the range of spiritual and religious activities people engage in within a provincial English town and find a relative shift from traditional forms of religious expression to novel forms of spirituality. They predict a potential “spiritual revolution” where the latter overtakes the former at some point in the future.19 A similar double process, of flourishing new spiritualities alongside declining traditional religion, is noted in Dick Houtman and Peter Mascini’s study of religious change in the Netherlands.20 They examine the extent to which new religious forms can be thought of as compensating (or failing to compensate) for declining affiliation with traditional religion.21 They conclude that there is an undermining of “the moral basis of the Christian tradition” but that “the growth of posttraditional types of religion” and non-religion has been stimulated.22

In a similar way, Christopher Partridge comments that the reality of the decline of institutional Christianity (at least in Europe) “cannot seriously be questioned”; in fact, “the popular Christian milieu … has collapsed” but “that collapse does not mean that the West has become fundamentally secular. Another religio-cultural milieu has taken its place.”23 The new milieu has, Partridge suggests, the potential to form the basis for a spiritual renewal built on “a confluence of secularization and sacralization.”24 Egil Asprem’s work has a similar leitmotif to Partridge’s, though he goes further by explicitly “moving away from the dichotomous positions of disenchantment and re-enchantment theories,” instead seeing “these issues rather as a negotiation in which spokespersons adopt various strategies and come up with various solutions to perceived problems.”25 Among the strongest statements of the significance of the persistence of religion is Wouter Hanegraaff’s assertion that “the weight of evidence demonstrates quite clearly that, regardless of how one defines ‘religion,’ it remains fully alive and shows no signs of vanishing. … It is not vanishing, but is being transformed under the impact of new circumstances.”26

While these writers emphasize the renewal effect of the new forms, others place the emphasis on the decline of the traditional. David Voas and Mark Chaves critique the notion that the United States defies the secularization thesis, as evidenced in a persisting religious landscape. They argue instead that high levels of religious affiliation and a slow rate of religious decline there have masked an underlying trend of decline.27 Nonetheless, to the extent that they propose the United States may simply match European patterns, and given that they do not exclude the growth of “diffuse spirituality,” their argument endorses the idea that generative processes remain present in the wider religious culture. Recognizing a flourishing of individualized forms of alternative religion (identifying them as “ ‘really’ religious”), Steve Bruce concludes that these forms of religion are more fragile, “harder to maintain,” and “more difficult to pass on intact to the next generation.”28 Although in Bruce’s account the ways that alternative forms of religion sustain religion-in-general are transitory and limited, in a similar vein to Voas and Chaves, his account reinforces the impression of dynamic processes linking conventional religious practices in decline with the exuberance of nontraditional and new forms.

Contrasted with the views of those suspicious of the secularization thesis, the interpretations of Voas and Chaves and of Bruce highlight the two intangibles at the center of the thesis: (1) that it is about a future state of human culture, and (2) that it depends on the definition of religion employed. Jeremy Morris’s discussion of secularization in Britain brings the two together.29 Morris calls for a “secularization” thesis with “the teleological assumptions … taken out,” permitting an analysis that “would register variations in religious practice over time, but seek to include these into a broader account of the development of British religion than is conventionally assumed.”30 In essence, Morris highlights the prejudgment of the classic secularization thesis that religious change (at least in “modern” societies) was inexorably headed towards decline, and he draws attention to the variation and dynamism inherent in all and any religious culture. All scholars discussed here—whether proponents or opponents of the view that religious change is tending to the elimination of religion—agree that religious culture is dynamic and energetic. The debate, though putatively about the destiny of religion in contemporary culture, pivots on the ways religion as a personal and social aspect of human culture is interpreted and understood. The endpoint of the changes under examination—religion’s demise or a spiritual renewal—is less important than its dynamism and energy.

Alongside the contemporary accounts of religious change that recognize the complexity and dynamism of the process, reassessments of classic secularization theses have suggested that these are not unequivocal in their assertion of religion’s decline. Warren Goldstein responded to R. Stephen Warner’s account of secularization (cited earlier) to suggest that Warner’s viewpoint “misunderstands and misinterprets the theory of secularization as articulated by the old paradigm” by seeing it as a relatively simple linear movement “from the religious to the secular, from the sacred to the profane.” Goldstein argues instead that a review of exemplars of the old paradigm suggests that their models contain a “dialectical” account of secularization that is an oscillation between periods of high religion and low religion, which can even paradoxically occur at the same time.31 He interprets classic proponents of secularization as indicating it is a “two-party system” where “neither side will be able to dominate over the other.”32

The central figure in Goldstein’s assessment is Peter Berger, whose work Goldstein characterizes as a classic expression of the old paradigm.33 The dialectic between the religious and the secular identified by Goldstein is somewhat hidden or implicit in Berger;34 nonetheless, Goldstein highlights that Berger laments secularization and concedes that “the supernatural survives ‘in hidden nooks and crannies of the culture.’ ”35 Furthermore, Berger has, in any case, “recently reversed himself” and implicitly conceded the dialectic; Goldstein says that “the early Berger argued that secularization was occurring, while the later Berger argued that a process of desecularization was occurring. He does not seem to acknowledge that secularization is a two-way process.”36 Thomas Luckmann shares much with Berger’s account; as Goldstein says, he “picks up where Berger left off.”37 While known as an advocate of secularization theory, Goldstein observes that Luckmann’s theory suggests that “religion has not disappeared from modern society, but instead has become “invisible” because “the individual has become sacralized.”38 The conclusion of Goldstein’s account is that

The paradox of secularization can be solved through a dialectical understanding of it as a two-way process. … Religious movements in the direction of rationalization, and social movements in the direction of secularization, spawn religious countermovements in the direction of sacralization and dedifferentiation.39

Though offering a somewhat different account of how religion is retained in the writings of these thinkers, Oliver Tschannen makes a similar observation that religion is nonetheless retained. He says Berger “stresses that religion survives in the most private and in the most public spheres”40 and that “Luckmann’s whole aim is to demonstrate that religion has not disappeared … but has merely become ‘invisible.’ ”41 Tschannen quotes Bryan Wilson with approval: “Religion is not eliminated by the process of secularization, and only the crudest of secularist interpretations could ever have reached the conclusion that it would be.”42

Building on the lead set by Goldstein and Tschannen, it is instructive to return to classic approaches to religious change with the presumption of secularization suspended. In Luckmann’s account of religious change, there is an important difference between churches as institutions and religions as elements of social worlds.43 Religion, Luckmann suggests, performs a social function: it is the expression of individual values that are shared in societies, and as such it is the expression of the unifying agent of a group of people (i.e., a society).44 Religious institutions have evolved by codifying and preserving these shared values, and they obtained their preeminence in society in relation to the extent to which they cogently carried out that function.45 However, there is nothing in the institution per se that is required for society to exist; only the underlying “world view”—the kernel of religion, able to exist without an institution—is required.46 In the natural course of events, religions come and go, and a particular religion may take its turn as the preeminent expression of a society’s worldview, but it may lose its place too and be replaced by another.47 There is, then, an oscillation in societies during this process. Over time, traditional church religion has become increasingly specialized and detached from the underlying unifying worldview of society and faded in importance.48 This having happened, and no “counter-church” or new “official” religion having emerged to replace the retreating old one, there has arisen a diverse and irregular economy of religions (including the old “official” religions in lesser garb) appealing to individuals in different ways and at different times.49 This has been compounded by a growing “consumer” approach to religion where the individual is the ultimate arbiter.50 So, Luckmann says, “we are not merely describing an interregnum between the extinction of one ‘official’ model and the appearance of a new one, but, rather … we are observing the emergence of a new social form of religion.”51 The new form is an “ ‘ultimate’ significance market” browsed by private individuals.52

In a more recent work, Luckmann develops his account of contemporary religion. He describes three grades of transcendent encounter in people’s lives: (1) “the ‘little’, spatial and temporal, transcendences of everyday life” that occur “whenever anything that transcends that which at the moment is concretely given in actual, direct experience can be itself experienced”; (2) “the ‘intermediate’ transcendences of everyday life” in encounters with referents to things that cannot be experienced directly (such as experiencing another’s body as referring to “the ‘inner’ life of the fellow being”); and (3) “the ‘great’ transcendences”—experiences that point to “something that not only cannot be experienced directly … but in addition is definitively not a part of the reality in which things can be seen, touched, handled.”53 According to Luckmann, experience of transcendence in its various flavors is universal, and the process of interpretation, systematization, teaching, and so on tends to the institutionalization of these experiences; “they become quasi-objective social realities”—i.e., institutional religions.54 However, Luckmann says that at a certain level of complexity, societies can no longer “maintain the social universality of an essentially religious world view oriented to the supremacy of a salvational articulation of the ‘great’ transcendences.”55 The consequences of this process, for religion, have “been customarily interpreted as a process of secularization, of the shrinking and eventual disappearance of religion from the modern world.”56 However, rather than seeing this as religion shrinking, he suggests it is better described as leading to a “change in the ‘location’ of religion in society … as privatization of religion.”57

Luckmann has been clear that religion in society is an institutional articulation of individual and continuing “experience on various levels of transcendence”;58 what he shows to be shrinkable is not the range of the transcendence in experiences (indeed, comments elsewhere in his article suggest that the range persists59), but instead the universalizability of references to transcendence (to little, great, or intermediate). It may be the case that “intersubjective reconstructions and social constructions shifted away from the ‘great’ other-worldly transcendences to the ‘intermediate’ and, more and more, also to the minimal transcendences of modern solipsism”;60 however, by Luckmann’s own account, intersubjective reconstructions and social constructions are not the same things as “wild” experiences of transcendence—they are merely the shared articulations and formulations of experiences of transcendence. Individual experiences of transcendence persist.

In the 1960s, Peter Berger argued that “today, it would seem, it is industrial society in itself that is secularizing” and “modern industrial society has produced a centrally ‘located’ sector that is something like ‘liberated territory’ with respect to religion. Secularization has moved ‘outwards’ from this sector into other areas of society.”61 The thrust is that social institutions come progressively less under the sway of overarching religious institutions and that a concomitant “secularization of consciousness” also takes place: “Put simply, this means that the modern West has produced an increasing number of individuals who look upon the world and their own lives without the benefit of religious interpretations.”62 While it is clear that Berger’s work of the 1960s and 1970s represented religion as in overall decline, he has famously changed his mind in recent times:

The assumption that we live in a secularized world is false. The world today, with some exceptions … is as furiously religious as it ever was, and in some places more so than ever. This means that a whole body of literature by historians and social scientists loosely labelled “secularization theory” is essentially mistaken.63

Secularization linked to modernization has, Berger says, “turned out to be wrong,” and “secularization on the societal level is not necessarily linked to secularization on the level of individual consciousness.”64

Notwithstanding his recent retraction, Berger’s earlier writings were suggestive of some persisting role for religion. His Social Reality of Religion referred to religion as “the audacious attempt to conceive of the entire universe as being humanly significant.”65 Because the endpoint for all humans is death, societies can be seen as “in the last resort, men banded together in the face of death,” and the power of religion depends “upon the credibility of the banners it puts in the hands of men as they stand before death.”66 Furthermore, while institutional religion was shown to have declined, people were instead “confronted with a wide variety of religious and other reality-defining agencies that compete for [their] allegiance”; thus, a kind of “religious market” or a system of “religious free-enterprise” has emerged.67 This presages Berger’s reassessment at the turn of the millennium that although “certain religious institutions have lost power and influence in many societies, … both old and new religious beliefs and practices have nonetheless continued in the lives of individuals, sometimes taking new institutional forms and sometimes leading to great explosions of religious fervor.”68 While the old pattern of secularization seems evident in western Europe, Berger says that “a body of data indicates strong survivals of religion, most of it generally Christian in nature, despite the widespread alienation from organized churches. A shift in the institutional location of religion, then, rather than secularization, would be a more accurate description of the European situation.”69

Both Luckmann and Berger have a considerable theoretical debt to Émile Durkheim. The central claim of Durkheim’s theory of religion is that it is an expression of society. For Durkheim, religion is “something eminently social” and collective that is expressed in shared rites and beliefs, and in individuals’ senses that they are part of something greater and that something greater inheres in them.70 Thus, common metaphysical ideas are expressions of the social superstructure that individuals participate in. While Durkheim’s account of religion is plainly less supernatural than conventional religious self-understandings (society in general provides the ultimate referent, rather than any conventionally transcendent power), religion in his scheme is unlikely to evaporate completely:

There is something eternal in religion which is destined to survive all the particular symbols in which religious thought has successively enveloped itself. There can be no society which does not feel the need of upholding and re-affirming at regular intervals the collective sentiments and the collective ideas which make its unity and its personality.71

In effect, according to Durkheim, unified social groups need unifying ideals to integrate them—those ideals are the elements of religion.

Durkheim says that religion “is nothing other than a system of collective beliefs and practices that have a special authority” through the adherence of a whole society and thus performs a special unifying and integrating function in society.72 As society changes, it is natural that old religions must fade and new ones arise.73 In Durkheim’s account, the replacement for religion, the supplanter of church religion, is qualitatively the same as what it has replaced (aside from the paraphernalia of “symbols and rites” or “temples and priests”74). Whether Durkheim is right that the religion of individualism is the natural replacement of traditional church religion, what is important here is his observation that there is an essential continuity (in Durkheim’s case, understood in strongly—if not unalloyed—sociological terms) between the old religion and the new spirituality. From the point of view of the secularization thesis, religion as social function will persist even if its object changes.

Durkheim’s representation, and that of Luckmann and Berger, has striking parallels with the nature of much contemporary spirituality. For example, Meredith McGuire writes that the new form of religiosity

turns pluralism, individualism, and freedom of choice, characteristic of the modern world, into religious virtues and advantages. … A meditation center or healing circle might attract a number of participants who individually are pursuing many different paths for their physical-emotional-social-spiritual well-being. They may be unified only by their common value of spiritual approaches to well-being.75

And Hanegraaff has highlighted the striking parallels between his account of New Age spirituality, in which “religion becomes solely a matter of individual choice and detaches itself from religious institutions,” and Durkheim’s expectations of religious evolution, which “sound like a veritable prophecy of the New Age movement.”76 Of course, the diversity of communities in which the Panacea Society’s healing found a following is perhaps not the unified social group Durkheim had in mind. Nonetheless, insofar as the Society did not demand adherence to doctrine, presented its healing as a kind of exultation of human perfectibility, and was plastic and unstable and subject to individual reformulation, it met the core criteria of Durkheim’s future religion and exemplified McGuire’s ecosystem of physical-emotional-social-spiritual searchers.

In his study of the 1960s as a turning point in popular spirituality, Hugh McLeod takes pains to use (unpublished) personal testimony to avoid relying solely on “celebrities or activists, whose experiences may be quite unrepresentative of the wider population.”77 Using a variety of written sources of evidence of religious understanding,78 Jeremy Morris sketches a historical approach to personal and interior spiritual lives that focuses on the internal element.79 Recognizing the problem of sources, Morris observes that “most of the accounts [he cites] come, naturally, from the highly educated”; however, “there is no intrinsic reason to believe that the spiritual world of the poor was any less complex … than was that of the rich and educated.”80 David Lyon enjoins researchers to “listen sympathetically to the accounts of believers,” as “taking seriously insider accounts … helps us avoid the elitism of some secularization dominated stories” and “chart the actual ‘meaning routes’ that individuals take in everyday life.”81

In turning to these kinds of sources, if considered within the bounds of conventional sociological practice that might divide religion into the public and the private, approaches such as these putatively seek to access the “private”; however, they might be better understood as entering a third realm between the two: the transcendent expressed in interactions between people (inside or outside churches). Kelly Besecke has identified this as “the noninstitutional-but-public kind of religion” in a “third sphere of society, neither institutional nor individual, but cultural.”82 Besecke says: “If private religion is located primarily inside people’s psyches, and public religion is that which engages politics or economics, or else takes place in the churches, then we lack a category for everything else.”83 Within this understanding, it is explicit that “religion is a meaning system and not a social institution.”84 Shaw’s account of the “domestic feel” of the theology of the Panacea Society is perhaps an example of the kind of interactive theology that expresses the interaction between spiritual seekers, although the Society’s reference points may be more conventional than those Besecke has in mind. Shaw shows how in the Panacea Society “ideas about God and what was happening in their midst were repeatedly refracted through a domestic lens,” and the core members “took up household and domestic images that are a key part of the Bible—though often missed—with alacrity,” reflecting their sense of female duty.85 Nonetheless, the Society’s core membership exemplifies a dynamic negotiation in spirituality and religion spanning the personal and the public realms, as well as conventional and innovative social and cultural movements. (This example is perhaps blunted by the fact that the Society attempted to establish itself as an institution along the lines of the Church of England its leadership knew so well.)

The idea of this kind of intermediary and dynamic religious space is coming to prominence, but it has long origins. It can be found, for example, in Don Yoder’s work on western folk religion in the 1970s.86 This is the region that Leonard Primiano calls “vernacular religion.”87 It is described by Bowman and Valk as “religion in everyday life, practical religion, religion as it is lived,” which is not studied with an emphasis on “artificial expectations of theological homogeneity or ‘orthodoxy’ ” but examines “what people do in relation to extra-liturgical praxis. … The overriding interest, is on what people in a variety of cultural, religious and geographical landscapes, think and say in relation to what they believe about the way the world is constituted.”88 This is one framework within which to interpret the various approaches of those who see the decline of mainstream religion as the decline of religion-in-general, and those who see it as part of a dynamic and broader economy. As Primiano has observed in the field of folklore studies, “the two-tiered model employed by historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and religious studies scholars … residualizes the religious lives of believers and at the same time reifies the authenticity of religious institutions as the exemplar of human religiosity.”89

In his discussion of vernacular religion, and in a bid “to redress a heritage of scholarly misrepresentation” and do “justice to the variety of manifestations and perspectives found within past and present human religiosity,”90 Primiano coins a new approach pertinent to the study of religion in all its forms. Vernacular has a range of meanings, and Primiano settles on two or three important senses of the term: “the indigenous language or dialect of a speech community”91; “simply ‘personal, private’ ”; and “of arts, or features of these: native or peculiar to a particular country or locality.”92 In his usage, Primiano refers to “the omnipresent action of personal religious interpretation[, which] involves various negotiations of belief and practice including, but not limited to, original invention, unintentional innovation, and intentional adaptation.”93 Thus, vernacular religion

takes into consideration the individual convictions of “official” religious membership among common believers, as well as the vernacular religious ideas at the root of the institution itself. Individuals feel their personal belief system as believers to be “official,” and they also at the same time feel the belief system disseminated by the agencies of the institutional hierarchy to be “official religion.”94

The significance of Primiano’s discussion of the scholarly approach to folk religion is pertinent in the study of the dynamics of modern religious change more broadly; it challenges religious studies to examine “the religious individual and the significance of religion as it is lived in the contemporary context.”95

The study of vernacular religion “understands religion as the continuous art of individual interpretation and negotiation of any number of influential sources” and recognizes that “all religion is both subtly and vibrantly marked by continuous interpretation even after it has been reified in expressive or structured forms.” The study of vernacular religion thus “shifts the way one studies religion with the people becoming the focus of study and not ‘religion’ or ‘belief’ as abstractions.”96 This is an attempt to grasp the “stubbornly ambiguous” “lived religion,” for all its inaccessibility, that lies at the base of all forms of religious expression.97

These analyses indicate a particular challenge to the study of religion in modern times. Previously, a historian of religion might validly engage with authorized and shared (normally published) accounts of experience of transcendence, thereby capturing something of a society’s consensus about the realm beyond immediate experience. In more recent times, in societies where accounts of transcendence are less susceptible to shared forms of expression, there is no convenient window into any general religious worldview. Indeed, the only source of this kind of information would lie in individual testimonies—such as those in which the Panacea Society’s Healing Archive is so rich. In societies where it is not assumed that there are individuals who can convey a shared metaphysics, the historian of religion must potentially treat everyone as a metaphysician and be prepared to study them as such. At root this is a problem of sources, because we are interested in the personal views of people who did not normally record their thinking in published form, or whose papers were not generally preserved for posterity or in other ways. The letters of the Panacea Society’s healing users provide a window into those views; they allow us to sample a multitude of people’s thoughts about transcendent matters across the twentieth century and across national and cultural boundaries. The method employed here uses these highly individual sources as valid and authentic expressions of the theological and metaphysical ideas of people who were not normally trained as theologians or metaphysicians.

The main part of the task outlined in this chapter will be carried out in the body of the book through an analysis of the letters of the Panacea Society’s water-takers. Prior to that, it is useful to examine some of the general trends and patterns of people’s correspondence with the Society’s Healing Department. While the overall pattern shows an early peak followed by decline and stagnation in application rates, indications of the gender breakdown of water-takers, and the stable intensity of people’s contact, are suggestive of some important themes in the nature of religious change in the twentieth century.

As we have seen, between its launch in 1924 and its closure in 2012, the Panacea Society’s healing received more than 122,000 applications from people in 102 countries or territories. The United States, Jamaica, and the British Isles were the main sources of applications, with the USA generating nearly 40,000 applications and Jamaica over 30,000. The British Isles, the third-largest source of applications, generated around 23,000 (overwhelmingly from England98). After the British Isles, there was a considerable drop in numbers to Finland, the fourth most significant national source of applications, which produced more than 3,000 applications overall.99

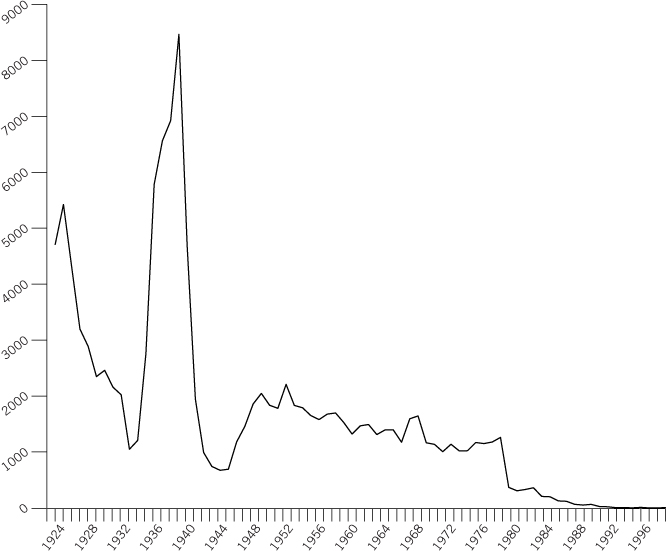

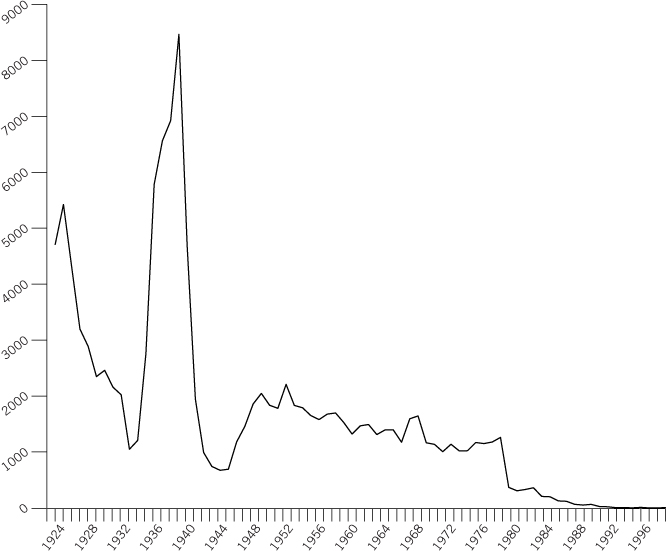

After an early peak followed by a second high point in 1939 (the relationship between the application data and war is discussed in chapter 6) with some recovery after a postwar collapse in numbers, the number of applications received each year steadily declined. The pattern is similar for many of the countries for which data is available in the archive.

Based on the sample of 3,894 applicants’ index cards (using the sample of the first 50 applicants stored in each of the 81 index card drawers),100 the average number of letters written by each applicant in the sample to the Society (excluding their application letter) was 5.3 during individuals’ careers as communicating users of the healing. If all those who applied and never wrote again are discounted from the sample (leaving 2,354), the average number of letters is 8.8 per applicant. The most voluminous correspondence identified in the sample amounted to 209 letters from a man (16017) who applied from New York in December 1927 and remained in contact until November 1989. A woman (16902) from Norfolk, England applied in March 1936 and went on to write 203 letters up to June 1986.101 The average duration of contact (excluding those identified as writing no letters after their application) was about three years and nine months (1,379 days).

There were steady declines in the duration of contact and in the overall number of letters written by each applicant to the Society over the course of the century (excluding those who did not write again after applying), with each applicant maintaining contact for an average of just over five years (1,864 days) and writing an average of fourteen letters to the Society if they applied in 1924–1933, and these numbers dropping steadily to 551 days of contact and 3.8 letters among those applying after 1983. Healing users were enjoined to write to the Society on a quarterly basis, and the average number of letters per year written by each applicant remained very steady; its low was the 1944–1953 intake (4.1) and its high was the 1924–1933 intake (4.8).102 Overall, the number of letters written each year by applicants ended the century at an average of 4.7 (for those who applied from 1974 onwards), almost precisely the same average number of letters written each year by applicants who applied in 1924–1933 (4.8). Thus, while the century saw people corresponding for less and less time and writing fewer and fewer letters, they continued to communicate at similar rates—that is, the intensity of contact remained the same, even if its duration fell.

CHART 3.1. Panacea Society Healing, global application numbers over time.

TABLE 3.1. Average duration of contact, number of letters written, and letters per year for index card sample of Panacea Society Healing users, analysed by decade of initial application, for all countries. (Excludes applicants writing no letters after initial contact.)

| Application decade |

Duration (days) |

Number of letters |

Letters per year |

Number in sample |

| 1924–33 | 1,864 | 14.0 | 4.8 | 547 |

| 1934–43 | 1,447 | 9.9 | 4.6 | 695 |

| 1944–53 | 1,619 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 291 |

| 1954–63 | 1,197 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 225 |

| 1964–73 | 1,009 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 263 |

| 1974–83 | 684 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 242 |

| >1983 | 551 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 91 |

TABLE 3.2. Average duration of contact, number of letters written, and letters per year for index card sample of Panacea Society Healing users applying from England, analysed by decade of initial application. (Excludes applicants writing no letters after initial contact.)

| Application decade |

Duration (days) |

Number of letters |

Letters per year |

Number in sample |

| 1924–33 | 1,509 | 11.7 | 5.1 | 361 |

| 1934–43 | 1,248 | 11.3 | 5.7 | 199 |

| 1944–53 | 1,235 | 8.2 | 6.7 | 46 |

| 1954–63 | 1,613 | 11.2 | 5.7 | 40 |

| 1964–73 | 781 | 4.1 | 6.6 | 37 |

| 1974–83 | 752 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 53 |

| >1983 | 262 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 20 |

The pattern holds for the two largest countries in the index cards sample: Jamaica and England. Indeed, each of these countries saw an overall increase in this intensity at the end of the century compared to the earlier period of healing. The intensity of correspondence (i.e., the number of letters per year) indicates the rate at which the decline in the number of letters written by applicants during their periods as users of the healing kept up with the decline in the duration of contact. An increasing intensity suggests that the number of letters written did not decrease as rapidly as did duration. (The prominent pattern is the overall consistency of the rate.)

The place of a female messiah was fundamental to the theology of the Panacea Society, and the group’s leadership and managers were predominantly women. The majority of applicants to the healing (more than two-thirds) were women. The levels of interest of women compared to men and the importance of the female in the Panacea Society’s theology may be reflections of wider trends in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century religious innovation. The Panacea Society is, for example, among the groups mentioned in Marta Trzebiatowska and Steve Bruce’s study of the relationship between religious innovation and women.103 The ratio of women and men who applied to the healing seems in line with research indicative of gender ratios in other alternative spiritual practices. For example, Liselotte Frisk’s study of New Age participants in Sweden suggests that 83 percent were women; 80 percent of those involved in alternative healing groups in New Jersey, USA, in research by Meredith McGuire were women; and Paul Heelas and Linda Woodhead concluded that females made up “80 percent of those active in the holistic milieu” in their area of study in northern England.104

TABLE 3.3. Average duration of contact, number of letters written, and letters per year for index card sample of Panacea Society Healing users applying from Jamaica, analysed by decade of initial application. (No records for 1924–33. Excludes applicants writing no letters after initial contact.)

| Application decade |

Duration (days) |

Number of letters |

Letters per year |

Number in sample |

| 1924–33 | – | – | – | – |

| 1934–43 | 1,016 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 407 |

| 1944–53 | 1,844 | 5.4 | 3 | 185 |

| 1954–63 | 868 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 145 |

| 1964–73 | 975 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 203 |

| 1974–83 | 652 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 156 |

| >1983 | 651 | 4 | 4 | 67 |

Of the 3,802 applicants in the index card sample whose index card records give an indication of gender, 2,598 (68 percent) are identifiable as female. Among the countries making up the larger proportion of the index card sample, females make up a larger proportion of the applicants, and the proportions are in striking agreement with the studies here cited. For example, the index cards from applicants with Jamaican addresses include 1,853 applicants with identifiable gender, and of these, 68 percent (1,264) are female. And 1,192 people with identifiable gender applied for the healing from English addresses, with 73 percent (866) women.

Women were also more likely to persist with the healing after their initial application; 37 percent (962) of the female applicants applied and made no further contact, whereas the equivalent figure for the 1,204 men in the sample was 43 percent (522). While, on average, men maintained a relationship with the Society for a shorter period of time and wrote fewer letters overall, on average the intensity of their contact with the Society (4.53 letters per year) was almost precisely the same as that for female water-takers (4.48).

TABLE 3.4. Average duration of contact, number of letters written, and letters per year for index card sample of Panacea Society Healing users, analysed by gender. (Excludes applicants writing no letters after initial contact.)

| Female/ male |

Duration (days) |

Number of letters |

Letters per year |

Number in sample |

| Female | 1,420 | 8.9 | 4.48 | 1,636 |

| Male | 1,305 | 8.5 | 4.53 | 682 |

The evidence of the sustained levels of intensity of contact with the Society (letters per year) is striking from the point of view of a classically conceived secularization thesis, though the steady declines in duration and number of letters might be expected. While the Society’s request that users of the water communicate on their progress quarterly no doubt contributed to intensity rates, from a traditional secularization viewpoint, it might be expected that this intensity would also decline as other metrics declined. Instead, the findings suggest that there is something consistent that underlies changing patterns of spiritual practice. Furthermore, as the level of intensity among the applicants after 1983 was about the same as it was for those who applied during 1924–1933 in the global sample and is consistent between genders, this aspect of spiritual engagement would seem to be less susceptible to outside factors than might be expected. Similarly, the broad pattern of a sustained intensity of contact in both Jamaican and English applicants suggests some continued and sustained interest somewhat independent of local conditions. While the overall decline in numbers applying to the Society may be evidence of the declining attractiveness of the Society’s offering (or of a general decline in the “volume” of religious affiliation in the wider society), the sustained intensity of contact is suggestive of a pattern of declining quantity but steady and somewhat universal quality of engagement as the twentieth century went on.