Man in Space

How did secrecy play a part in the Space Race?

The USSR kept everything about its programs secret from both the international community and its own people, while the United States shared every success and failure.

|

|

The launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union was more than a turning point in the race to space. It was a huge turning point in the Cold War, too. The United States had viewed the Soviet Union as incapable of orbiting a satellite, but when Sputnik passed overhead, the country was reminded how wrong it was.

Khrushchev, pleased with the international recognition Sputnik had attracted, boasted of stockpiles of nuclear-armed ICBMs ready to launch at a moment’s notice. Unable to verify the Soviet leader’s claim, President Eisenhower had to take Khrushchev at his word.

The U.S. Air Force had a more powerful rocket in the Atlas missile, but the Americans didn’t have a huge arsenal of them—yet. Faced with a “missile gap,” the U.S. government decided it needed more missiles to ward off the Soviet threat. It was a chilling thought for the country and the world.

President Eisenhower wanted to keep American space exploration separate from the military as much as possible. To catch up to the Soviets, however, it was time to combine efforts into a single program. To do this, most programs from the Army, Navy, and Air Force were combined into a civilian agency that was responsible for the peaceful exploration of space. Some military programs still operated outside this one organization.

Von Braun, who had put the country into orbit, would join the program, but not as its head. Instead, he would work on the giant rocket of his dreams, a rocket that could take people to the moon.

After the end of the Cold War in 1991, records showed the Soviets had only eight ICBMs in 1961.

THE BEGINNING OF NASA

On October 1, 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) opened its doors to take on the challenges of space flight. Just weeks after its birth, NASA made headlines when it announced the man-in-space program. Its goals were to put a person in orbit, study how space flight affects people’s minds and bodies, and bring them safely back to Earth. Everyone knew the unstated hope—to be first.

But before its goals could be accomplished, NASA had to answer a lot of questions. Could humans function in space? Could they breathe, eat, and sleep there? Could they even go to the bathroom normally? Would they go crazy being so far from home? Could a rocket be made reliable enough to safely send people on such a risky trip? What kind of spacecraft could bring them back? And who would even consider such a dangerous job?

In January 1959, a quiet call went out for pilots with some very specific requirements. They needed to have college degrees, be no taller than 5 feet, 11 inches, be no heavier than 180 pounds, and have extensive experience flying the newest high-performance fighter jets.

The recruits were subjected to every kind of medical test imaginable, plus some that weren’t. Blood tests were taken, and heart rate and lung capacity were measured. The men were spun in a giant centrifuge to simulate the strong g-forces they would experience during launch. Long periods of isolation, sleep deprivation, and sudden noise were used to test their ability to mentally withstand the hazards of flying in space.

Despite the Soviet Union’s lead in the Space Race, all the astronauts expressed confidence in the NASA program and were eager to be the first person in space.

|

|

The Mercury Seven

Credit: NASA/Langley Research Center

On April 9, 1959, the Mercury Seven were introduced to the world. The seven future astronauts—Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton—became instant celebrities. But, they still needed a spacecraft.

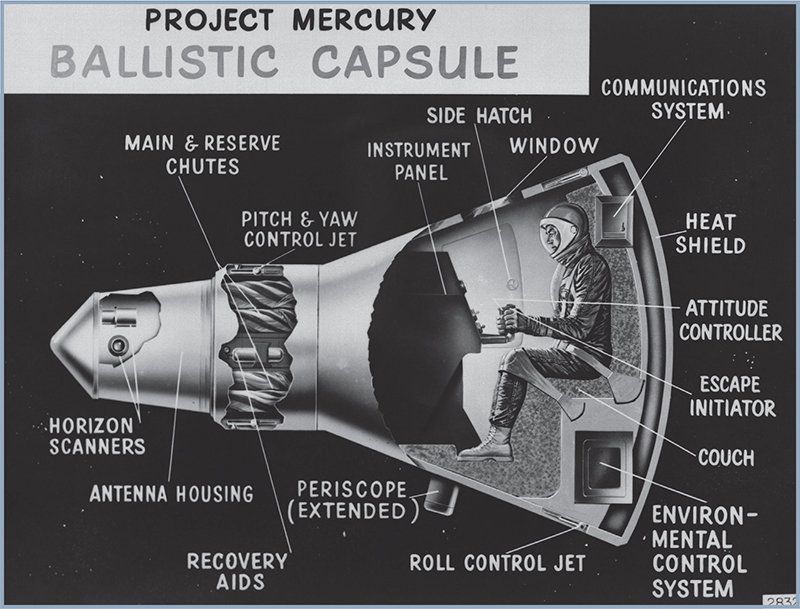

THE MERCURY CAPSULE

Early rocket experiments showed that space was a very dangerous place for humans. Scientists discovered that above Earth’s atmosphere, astronauts needed protection from the vacuum of space. Without protection, bubbles would quickly form in their blood, causing it to boil.

The craft also had to be strong enough to withstand the intense forces of the launch and the estimated 3,000-degree Fahrenheit (1,649-degree Celsius) heat of reentry, all while being as light as possible. And it needed to work perfectly, every time. The task of designing such a spacecraft fell to aeronautical engineer Max Faget (1921–2004).

Faget’s design for the first American spacecraft looked nothing like the spaceships of science fiction. It was small, measuring just 6 feet, 10 inches tall and 6 feet, 2½ inches at its widest. Shaped like a bell, the miniscule capsule had just enough room for one person. And it had just enough equipment to keep that person alive.

Small retro-rockets would slow the capsule’s speed, and its blunt end was covered by a heat shield to protect it against the high temperatures of reentry. Parachutes would guide the craft to an ocean landing, where ships would pluck the capsule and astronaut from the water.

It was an ingenious design, but it wasn’t the only spacecraft being readied for human flight. While the American effort was front-page news around the world, the Soviets were secretly working on their own craft and the men who would fly in it.

A diagram of the first Mercury capsule from 1959

credit: NASA

While the selection of the Mercury Seven drew worldwide attention, the Soviet’s search for their first cosmonauts was held in secrecy, even from the candidates themselves. The Soviet search included hundreds of highly skilled pilots, who were kept in the dark about the true mission. At first, the candidates were told only that they would be evaluated for a “special flight,” but the extensive testing of their mental and physical abilities led them to guess what they were being prepared for.

Like their American competitors, each hoped he would be the one to beat all the others and become the first person in space. But none of them were sure how they’d get there. And who was in charge? While von Braun was a part of NASA and a household name in the United States, Korolev’s identity was kept secret, even from the chosen pilots.

Until their first meeting, the cosmonauts knew Korolev only as the Chief Designer, a man with a reputation for taking big risks that almost always seemed to pay off. It was Korolev who gave them their first view of the vehicle engineered to take them to space.

VOSTOK

Like the Mercury capsule, the Soviet spacecraft looked nothing like the jets the pilots were used to. There were no wings and no engines. But Vostok was also very different from the bell-shaped Mercury.

Although smaller than a fighter jet, the Vostok was much larger than the Americans’ spaceship, weighing 10,430 pounds compared to the Mercury’s 3,000. The difference in size was due to the rockets each country would use to send them into space. Korolev’s R-7 was a much more powerful machine than the Atlas D rocket used for Project Mercury, and could carry much more mass into orbit.

FAILURE

The first test launch of the Vostok spacecraft in May 1960 began well, with the R-7 rocket performing perfectly and placing the unmanned capsule into orbit. But at the end of the mission, the retro-rockets did not burn long enough to slow the capsule for reentry. The tiny sphere skipped off the atmosphere like a stone across a pond, out of fuel and stuck in orbit. If a cosmonaut had been aboard, he would have died when the oxygen ran out.

Fortunately, the next test of the Vostok craft went much better, carrying the dogs Belka and Strelka into orbit and back home safely. The Soviets were now confident Vostok was ready for its intended passenger.

Three months after the dogs’ flight, an unmanned Mercury-Redstone rocket stood ready on a launch pad at Cape Canaveral, Florida. After several delays, NASA and von Braun were desperate for a successful flight.

Politicians, military leaders, and members of the press gathered to watch. As the countdown clock reached zero, the rocket immediately roared to life—and just as quickly went quiet. Suddenly, the escape tower shot free from the capsule, careening through the sky. Onlookers ran for cover as it crashed on a nearby beach. Moments later, the parachutes popped out from the top of the Mercury capsule, covering the motionless rocket.

While both countries celebrated their successes, only the United States made its failures public. It was an embarrassing failure, but it was soon overshadowed by a more dangerous incident that followed.

An Air Force U-2 Dragon Lady

credit: U.S. Air Force

The pilot of the U-2 spy plane, Gary Powers, was put on trial and sentenced to hard labor in a Soviet work camp. He was eventually freed in 1962, when he was exchanged for a Soviet spy.

That same summer of 1960, American pilot Gary Powers’s U-2 spy plane was shot down while on a spy mission over the USSR. The American government denied it was a surveillance plane, but the capture of the pilot and the plane’s wreckage made its mission obvious. Furious, Khrushchev canceled a planned summit with President Eisenhower, calling the American president untrustworthy.

With the rocket failure and the capture of an American pilot, many Americans hoped that the presidential election of 1960 would help the country take the lead in the Space Race and regain its standing with the rest of the world. The new, young U.S. President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) seemed to be just what the country needed—a fresh start.

Check out the three-part press conference that introduced the Mercury Seven to the world here.

NASA press conference 1959, part 1

NASA press conference 1959, part 1

WHO WOULD BE FIRST?

The public wanted to know who would be the first to sit atop a Mercury-Redstone rocket. If the choice was left to the people, they’d have picked John Glenn (1921–2016). The clean-cut, all-American figure was by far the most popular and well-known of the group.

Within the Mercury Seven, however, Glenn was not the most popular. His squeaky-clean image and occasional clashes with the others meant that while he was respected for his work, he was not their choice to make history. When NASA asked the Mercury Seven who should be first, they suggested Alan Shepard (1923–1998).

Born in the small town of East Derry, New Hampshire, in 1923, Shepard was interested in flight at a young age and considered the aviator Charles Lindbergh a hero. While excelling at math and science in high school, he also took jobs working on, in, and around airplanes. After serving in the Navy during WWII, Shepard graduated from flight school and became one of the youngest test pilots ever.

For the American astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts, training for the first space flight reached a new level of intensity in 1961. While the cosmonauts worked in absolute secrecy, every move the Americans made was big news.

|

|

Intelligent and level-headed, he was respected by every member of the Mercury Program. The selection of Alan Shepard even made news in the Soviet Union, but, as with most things, it kept its choice for the first cosmonaut secret. Now the world knew who the Americans would send into space—would he beat whomever the Soviets selected?

YURI GAGARIN

Yuri Gagarin’s (1934–1968) upbringing was very different from Shepard’s. Gagarin was born in Klushino, Smolensk, and his family was extremely poor. Their village had no water and no electricity. The future cosmonaut was not even able to attend school, and instead learned to read and write at home. His family suffered greatly during the German invasion of World War II—they had to live in a pit while enemy soldiers took their home.

After the war, Gagarin attended makeshift classes and was considered a bright student. He went on to study farming machinery at a technical college. It was at an airfield near his school that Gagarin got his first real taste for flying, and soon he joined the military to become a fighter pilot.

When officials began asking for volunteers to join a secret project, he was quickly selected, but he was forced to keep this secret even from his family. Once selected as the best pilot by the State Commission, Gagarin was ready, confident that he and the Vostok spacecraft would make history.

POYEKHALI! (“LET’S GO!”)

After the embarrassing failure to leave the launch pad, NASA quickly rebounded with several Mercury-Redstone tests, including the suborbital flight of a chimpanzee named Ham. To astronaut Alan Shepard, Ham’s flight proved that the rocket and capsule were safe. But several at NASA, including von Braun, decided that one more test was needed. Shepard’s March 24 flight was changed to an unmanned flight, and he was scheduled instead for late April.

All he could do was watch the final successful test and wait. Everyone was wondering just how close the Soviets were to their shared goal.

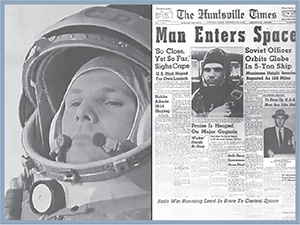

At 9:07 a.m. on April 12, 1961, an R-7 rocket roared to life and left the Kazakhstan steppe. The booster worked perfectly, accelerating its Vostok capsule to 17,400 miles per hour and an altitude of 203 miles. Inside, the world’s first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, looked through the small portholes at Earth below. He’d come a long way.

After nearly an hour, Gagarin’s capsule had taken him back almost to where he’d started, almost one complete orbit around Earth. With mission control guiding the Vostok, Gagarin had time to take in the experience.

Then, the retro-rockets fired and the craft began to spin. The instrument module had failed to separate properly, and was still attached to the reentry capsule by a cable. If the craft was unable to break free, it could be destroyed by the crushing pressure and searing temperatures of reentry. Thankfully, the cord snapped and the sphere righted itself as it plummeted through the atmosphere.

The headline from Huntsville, Alabama, proclaims Gagarin’s historic flight.

credit: NASA

After the parachute opened, the external hatch fell away, and, with a tremendous roar, Gagarin’s ejection seat shot him clear of his craft. Local villagers were startled by the parachuting man. Just 108 minutes ago, he was unknown to the world, but now he was cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the first person in space.

The reaction around the world was disbelief. The Soviets had bested the Americans again. Now the Soviets could boast of having put the first person in space. Headlines proclaimed the Soviet triumph, calling the accomplishment one of the most important in world history. President Kennedy, in only his third month in office, congratulated the Soviets on their success.

It was a blow to America’s pride, and another embarrassing loss to their Cold War opponents. But it was about to get much worse for the new president.

Just days after Gagarin’s flight into history, a small group of Cuban exiles launched an invasion of Cuba to drive out the communist government there. The United States had promised these rebels air support, but the air support never came, and the Bay of Pigs invasion was easily stopped by the Cuban army. Fidel Castro, Cuba’s leader, was furious and turned to the USSR for help. Instead of liberating Cuba, the invasion only drove the country to side more strongly with its communist allies.

The failed effort put even more pressure on the young president. The United States’ image as a powerful and prosperous nation was threatened. Was communism better at producing scientists and engineers than the West? Kennedy wanted a victory to prove the country capable of beating the Soviet system. NASA hoped it had an answer.

Watch this video that combines real footage of the mission with a computer simulation to give you the entire experience! How do you think Shepard’s experience of manual control made the experience different from Gagarin’s flight?

FREEDOM 7

In the early hours of May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard suited up and boarded Freedom 7, the Mercury capsule that would carry him into space. Unlike Gagarin’s flight, Shepard’s would be suborbital and would last a fraction of the time the Soviet cosmonaut spent circling the earth.

At 9:34 a.m., the rocket carrying America’s first astronaut left its launch pad as the world watched in anticipation. The Redstone performed flawlessly, putting Shepard on a suborbital path. As Freedom 7 rotated into position for reentry, Shepard’s hands rested on the controls. Unlike Gagarin, he could control his craft.

When the capsule reached its highest altitude of 116.5 miles, Shepard was only about four and a half minutes into the flight. Even strapped to his seat, the second man in space could feel the strange sensation of weightlessness.

Minutes later, Shepard felt a jolt as the retro-rockets fired, slowing the craft as it began its fall back to Earth. Another jolt meant the parachutes deployed at the proper altitude, slowing the craft’s speed even more. After 15 minutes, Freedom 7 splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, 300 miles from its launch pad. America had its first astronaut.

With Alan Shepard’s successful flight, America now had the ability to put a person in space. But the two flights were very different. Vostok was a much larger and more capable craft, despite the cosmonaut having to land by parachute. And the Redstone wasn’t even powerful enough to put the smaller Mercury into orbit. It was only the beginning of the Space Race, and the Soviets had a very big head start. The United States needed a win.

President John F. Kennedy set the goal for the Space Race on May 25, 1961. You can watch and listen to the speech at this website. Can you think of other moments in history when a presidential speech had such a resounding influence?

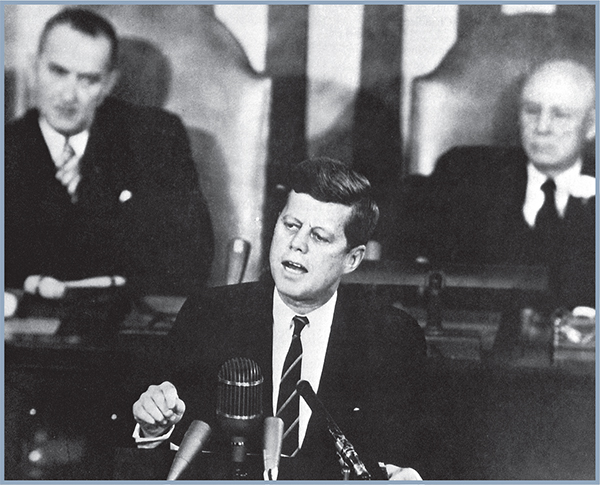

TO THE MOON

After the Bay of Pigs invasion and the capture of Gary Powers in the U-2 spy plane, the United States found success with the flight of Alan Shepard. Not wanting to waste the huge public support for America’s early space program, President Kennedy looked for a way to show the world that America’s democracy and capitalism were stronger than the communist system.

President John F. Kennedy, speaking to Congress May 25, 1961

credit: NASA

After consulting with Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973), a strong supporter of the space program, he decided that beating the Soviets in space would be a unifying goal and a demonstration of America’s technological expertise. On May 25, 1961, President Kennedy gave a rousing speech to Congress, outlining America’s goals to counter the communist threat.

Suddenly, the Space Race had a finish line—the moon. Von Braun was ecstatic. His proposed Saturn rocket program would receive the necessary funding it needed to carry people to the moon, and ideally beyond. It was the challenge he had waited for since his childhood. Korolev, also aware of the finish line, remained in the shadows. But the Chief Designer had his own plans for a Soviet moon rocket.

Write down what you think each word means. What root words can you find to help you? What does the context of the word tell you?

astronaut, atmosphere, cosmonaut, eject, g-force, heat shield, mass, plummet, retro-rocket, surveillance, and vacuum.

Compare your definitions with those of your friends or classmates. Did you all come up with the same meanings? Turn to the text and glossary if you need help.

•What is the connection between politics and space exploration in each country?

•How did the Bay of Pigs incident affect relations between the two countries? How did the event highlight the suspicion that already existed?

SPLAT!

Protecting an astronaut from the dangers of space travel is a difficult task. The early spacecraft used by both space programs were small, cramped capsules designed with only one thing in mind—bringing the passenger back safely to Earth. Can you do the same? Here’s your challenge: design a “space capsule” to protect a raw egg from the forces of gravity!

There are lots of ways to protect your eggstronaut! Check out this video for some ideas to ensure your intrepid explorer survives the fall!

•Assemble the materials you have on hand. What can you use that could protect an egg?

•Design your space capsule. How will you use your materials? What is the best way to protect your “eggstronaut”?

•Assemble your craft and test it (you can try using a hard-boiled egg first) by dropping it from shoulder height. Make any changes needed.

•Try dropping your capsule with its passenger from differing heights. How does your design hold up? What is the biggest drop your eggstronaut can survive?

To investigate more, challenge others to a contest. Compare your strategies and designs. What materials and ideas work best?