Small Steps to the Moon

Was the race to the moon worth the risk?

As both countries took more risks in the effort to land a man on the moon, the danger involved in space travel became more apparent. Even though scientists and engineers took every precaution possible, the lives of the astronauts and cosmonauts still hung in balance.

|

|

The Space Race now had the moon as its goal, but there was a lot to learn about spaceflight before anyone could step onto the lunar surface. So far, both countries had proved a person could survive in space for a short time, but a trip to the moon would take days.

Could people really survive in space that long? Could a pilot navigate the unfamiliar and unforgiving environment? How would radiation, long periods of weightlessness, and isolation affect people? The only way to find out was to keep flying.

The Soviets had put a man into orbit, while the Americans still didn’t have a reliable alternative to the smaller, less-powerful Redstone. For the Americans to overcome the head start of the Soviets, the Mercury program needed to be a success.

GUS GRISSOM AND LIBERTY BELL 7

Only eight weeks after President Kennedy’s speech to Congress, Gus Grissom’s (1926–1967) Liberty Bell 7 roared into space on a flight meant to be a repeat of Shepard’s historic trip. Grissom, an Air Force veteran and experienced test pilot, was up to the challenge.

In 1999, Liberty Bell 7 was recovered from a depth of 15,000 feet—deeper than the Titanic! It is now on display at the Kansas Cosmosphere.

After Shepard’s trip, a few changes were made to the Mercury capsule. As requested by the astronauts, a large window was installed, giving Grissom a spectacular view. Once in space, he marveled at his view of Earth, describing it as “fascinating.”1

More importantly, however, a new hatch with explosive bolts replaced the hand-operated one. The manual hatch took more than a minute to open, which could cost an astronaut his life in an emergency. The new hatch would open instantly with the flick of a switch.

The retro-rockets fired on schedule, slowing the craft for reentry. About 15 minutes after launch, Grissom’s capsule splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean right on target. The mission was a complete success—but it wasn’t over.

As Grissom prepared the capsule for recovery, he was startled by a sudden explosion. The hatch had blown without warning, quickly flooding the capsule with seawater. Still in his spacesuit, Grissom had no choice but to pull himself out of the capsule and into the choppy seas as the recovery helicopter approached.

While the pilot tried to lift the capsule, Grissom found himself in danger of going under. Water was slowly filling his suit through an open port, and as the waves rose higher, he found it harder to keep his head above water. Fortunately, a second helicopter plucked him from the rough seas. The first helicopter had to let the capsule go. As an exhausted Grissom was taken to the recovery ship, Liberty Bell 7 sank beneath the waves.

The dramatic rescue at sea reminded the public just how dangerous all parts of spaceflight could be. NASA had come close to losing an astronaut on just the second flight of the Mercury program, and they had yet to match the difficulty of Gagarin’s flight.

Just a few weeks after Grissom’s near drowning, the Soviets wowed the world with another impressive flight.

Liberty Bell 7 before it was lost beneath the waves

credit: NASA

On August 6, 1961, it was Gherman Titov’s (1935–2000) turn to make history. The second person to orbit the Earth, at 25 Titov was (and is still) the youngest person to travel in space. Although the R-7 and Vostok 2 worked perfectly, Titov himself ran into problems. Shortly after reaching orbit, he felt as though he were tumbling, even though the capsule remained steady. Soon, nausea, dizziness, and headaches followed, making it difficult for him to complete some of his scheduled tasks.

About half of all astronauts report feeling sick when they reach orbit. Scientists call this “space adaptation syndrome,” and it is usually overcome in a matter of hours or days.

Titov’s body adapted to the strange environment. Finally able to focus, he observed through the Vostok 2’s portholes a view of Earth only three others before him had seen.

He ate and drank, then dozed off for a scheduled nap. After 16 revolutions around the Earth, Vostok 2’s retro-rockets fired. As the craft entered the atmosphere at terrific speed, the delighted cosmonaut watched through the portholes as intense heat and pressure surrounded the small sphere.

“I had the feeling that our earth is a sand particle in the universe.”

—Gherman Titov, while on Vostok 22

|

|

News of Titov’s successful flight and landing was broadcast around the world. He’d beaten Gagarin’s single orbit. He also drank, ate, and even slept in space. The Soviets were clearly far ahead of NASA.

Even though the Soviets were breaking down barriers in space, they were building them on Earth.

By the beginning of 1961, 10,000 people a month fled East Berlin for West Berlin, trying to escape the worsening living conditions and oppressive East German government. Desperate to stop the loss, Moscow came up with a plan to stop the East Germans crossing the border. On the morning of August 13, just a week after Titov’s ground-breaking flight, citizens from the two Berlins woke to soldiers laying the first bricks in what would become the most visible symbol of the Cold War—the Berlin Wall.

By the end of its construction, the wall stood about 12 feet tall and stretched more than 100 miles, encircling all of West Berlin. Sentry towers and land mines surrounded the wall, and guard dogs and snipers patrolled it, sometimes using deadly force to prevent anyone from the East crossing to the West.

Western nations protested the drastic move, calling on Moscow to open the border. But the East Germans, under the direction of the Soviet Union, refused. On opposite sides of the wall, American and Soviet forces faced each other across a divided city. The world watched nervously, wondering how long the stalemate could hold, and what it would take to break it.

Then, on October 30, 1961, the Soviet military detonated the largest nuclear bomb the world had ever seen. Called the Tsar Bomba, it released the energy of 50 megatons of TNT—more powerful than all the bombs and explosives used in World War II combined.

Such a weapon terrified the American people. President Kennedy urged people to build fallout shelters as schoolchildren carried out “duck-and-cover” classroom drills. Needing hope, the people of the United States looked to John Glenn.

While the Redstone booster was reliable, it was not powerful enough to reach the speed necessary to carry it around Earth. To put Glenn into orbit, NASA needed a much larger and more powerful rocket—the Air Force’s Atlas missile. Atlas was America’s first true ICBM, capable of delivering a nuclear warhead anywhere inside the Soviet Union. But almost half of the rocket’s test launches ended in fiery explosions—not exactly the result NASA was looking for.

After a number of test flights, on November 29, 1961, an Atlas booster carried the chimpanzee Enos into orbit and his Mercury capsule brought him safely back to Earth. The Mercury-Atlas combination was declared safe, and the first American orbital flight was scheduled for early 1962.

On February 20, 1962, the world watched as John Glenn rode the Mercury-Atlas into the history books. While the rocket performed well, Glenn’s Mercury capsule, Friendship 7, had problems as soon as he reached orbit. Automatic systems that controlled the craft’s positioning failed, requiring the astronaut to take over. For the experienced pilot, this wasn’t a problem. But, unknown to Glenn, something more serious was making mission control very worried. As he circled the earth, a warning light indicated that Friendship 7’s heat shield was loose. Those on the ground knew that if the heat shield failed, Glenn wouldn’t survive the intense heat of reentry.

During the Cold War, schoolchildren practiced duck-and-cover drills to prepare for a nuclear attack. Check out this video used to teach children to how to duck and cover.

On November 29, 1961, a chimpanzee named Enos became the first primate to orbit Earth. His successful Mercury-Atlas flight proved the more powerful Atlas rocket was safe, and paved the way for John Glenn’s historic launch.

|

|

Mission control decided not to tell Glenn about the warning light, instead instructing him that the retro-rockets would remain strapped to the bottom of the craft for reentry. Once used, the retro-rockets were usually discarded, but engineers hoped they would hold the heat shield in place.

John Glenn and his Friendship 7 capsule

credit: NASA

After completing three orbits, the retro-rockets fired and Friendship 7’s fall back to Earth began. It was a tense moment for everyone as they waited to hear from Glenn. Nobody was sure if the heat shield would hold or if America’s first astronaut in orbit would also be the first astronaut to die. After five long minutes of radio silence, Glenn’s voice crackled over the speakers at mission control.

Mission control, along with the entire country, breathed a sigh of relief. America finally had a flight to rival the Soviet Union, and Glenn was given star treatment. Millions lined the streets of New York City to watch him and his fellow astronauts in a parade as ticker tape rained down.

In a speech to Congress, Glenn stated that the United States was committed to peaceful and open exploration of space. He pointed out that the American space program was conducted openly and in front of the world. Although he didn’t name the Soviet Union, it was clear that Glenn believed the secrecy around their rocket program did little to lessen the tensions of the Cold War.

SCIENCE IN SPACE

After the nationwide celebration of John Glenn’s orbital flight, attention turned to Scott Carpenter (1925–2013) and his Aurora 7 spacecraft. The first three launches satisfied NASA that the Mercury capsule could keep an astronaut safe, and it was now time to start doing more research on the scientific and practical effects of spaceflight.

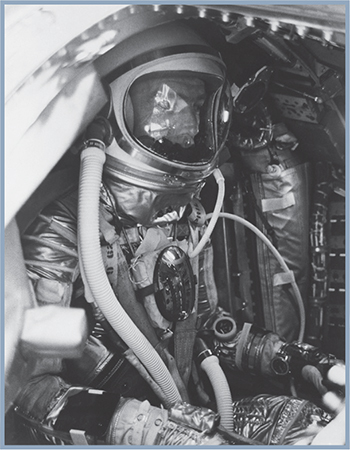

Scott Carpenter inside the Aurora 7 Mercury capsule

credit: NASA

If the United States was to land on the moon, a number of questions had to be answered. How would fluids behave in space? How could a pilot navigate a spacecraft? Before Carpenter’s flight, astronauts had eaten only nutritional paste squeezed from a tube. What would happen if an astronaut ate solid food? To answer these questions, Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7 lifted off on May 24, 1962.

Once in orbit, Carpenter began his experiments. He took pictures of Earth’s horizon to help design a navigation system to take astronauts to the moon. Maneuvering the capsule proved to be easy and fun for the new astronaut. But the solid, freeze-dried “food cubes” turned to crumbs during launch, making them a danger to the delicate instruments. Even the candy bar he was given melted from the heat in the cramped cabin. Despite the disappointing snacks, Carpenter enjoyed the ride and the magnificent view of Earth below.

While Scott Carpenter had achieved his mission objectives, many at NASA were upset with the near-disastrous loss of fuel and the 250-mile miss of the landing zone. Carpenter never flew in space again, but became an aquanaut with the Navy.

After five orbits, Carpenter prepared the capsule for reentry. While putting Aurora 7 into the correct position, he discovered that the system used to change the pitch of the craft had malfunctioned. He was suddenly very low on the fuel needed to keep his ship lined up properly for reentry. Without the correct positioning, the capsule could burn up as it plummeted through the atmosphere. Luckily, the capsule’s design allowed it to right itself as it fell. Aurora 7 splashed down safely in the Atlantic, although 250 miles from the intended landing zone.

Carpenter had fired the retro-rockets late, distracted by the problems with pitch and fuel. As the recovery ships steamed toward him, news reports declared NASA had “lost” an astronaut at sea, and that the military was combing the ocean to find him.

Thankfully, Carpenter and his capsule were picked up about three hours after splashdown. The newest astronaut was found floating comfortably in his life raft.

It seemed the Americans were about to move ahead in the Space Race. However, the Soviets weren’t willing to give up their lead.

A RENDEZVOUS IN SPACE

On August 11, 1962, cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolayev (1929–2004) left the Baikonur Cosmodrome aboard Vostok 3. The West assumed it was a repeat of the Vostok 2 flight and expected to hear little from the secretive Soviets. However, the launch of Pavel Popovich in Vostok 4 the very next day had the entire world paying attention to the Soviets once again.

Soviet television broadcasts showed the joyous pilots floating free in their cabins, a first for manned spaceflight. The cosmonauts performed experiments and even signaled to one another over radio. Vostok 3 spent nearly four days in orbit, while Vostok 4 stayed up for almost three days. It was an impressive, record-setting pair of missions.

While the Soviet accomplishment was stunning, it wasn’t quite what it appeared. In fact, Vostok capsules weren’t able to change their orbits, as many at NASA assumed. The timing of the Vostok 4 launch allowed the two craft to come within four miles of each other, but with only small maneuvering rockets, they quickly drifted apart in space. The Soviets were happy to let the United States believe otherwise, and Khrushchev was very pleased with the results.

If the reports were true, the Soviets’ ability to maneuver and rendezvous in space was way ahead of anything Project Mercury could do. How could the United States beat them to the moon?

|

|

THE PERFECT FLIGHT

Once again in the shadow of the Soviets, NASA had no choice but to press on with more Mercury flights. The orbital rendezvous was a difficult feat to follow. The task fell to Navy pilot Wally Schirra (1923–2007). Schirra was an excellent choice for a mission that would push the limits of his Sigma 7 craft.

A smooth October 3, 1962, launch on an Atlas booster put Wally Schirra in a near-perfect orbit. Right away, he got to work testing newly designed thrusters and Sigma 7’s navigation systems. He proved that a pilot could navigate precisely in space using only the earth and stars, an important step in flying to the moon.

Walter “Wally” Schirra was the only astronaut to fly Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions.

During his nine-hour flight, Schirra tested the electrical and life-support systems to work out emergency routines if a capsule were to lose power. Once the testing was finished, Schirra fired the retro-rockets and returned to Earth, completing the most successful and problem-free Mercury flight yet. It was so successful, in fact, that NASA decided to speed up the program and go ahead with an even longer mission for the final Mercury flight. But only days after Schirra’s successful mission, a new and frightening development in the Cold War threatened to end the race to the moon, and even all life on Earth.

NUCLEAR CRISIS

After the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba’s communist leader, Fidel Castro, asked the Soviet Union for help defending the island from American aggression. Secretly, Soviet politician Nikita Khrushchev approved the shipment of nuclear missiles to the island nation, placing them just 103 miles from the Florida coast. American spies in Cuba noticed strange shipments arriving, and a U-2 spy plane confirmed the U.S. government’s suspicions.

You can watch President Kennedy’s Oval Office address during the Cuban Missile Crisis at this website. How does President Kennedy’s language compare to the language politicians use today?

Many of President Kennedy’s advisors urged him to invade, hoping to rid the island of both the nuclear threat and communism in one blow. Only a month before, the Soviet government had promised the buildup in Cuba was only defensive, and that their superior R-7 missile technology made putting nuclear missiles close to the United States unnecessary. The nuclear arms in Cuba were a violation of that promise, and threatened to turn the Cold War into a hot one.

On October 22, 1962, President Kennedy addressed the American people by radio and television. Instead of an invasion, he declared a naval blockade of Cuba.

Unlike the Soviet blockade of West Berlin, the Americans would allow food and goods to pass, but no weapons. President Kennedy promised that if the Soviets did not remove their nuclear missiles from Cuba, the United States would take further action. And if a missile was launched toward any nation in the Western Hemisphere, it would be considered an attack on the United States, and the United States would respond in kind. Kennedy sent a clear message that Americans would not tolerate Soviet missiles so close to home—but nobody was sure how Moscow would respond.

It was a tense and terrifying time, not just in the United States, but around the world. With both militaries on highest alert, a wrong move at any moment could start the next world war. Although it was always known that the technology used to send men to space was the same technology that could cause a nuclear war, it was never clearer than at the end of 1962. Were the rockets the astronauts and cosmonauts rode really about peaceful exploration of space or had the Space Race set the stage for nuclear war?

The first photo that showed Soviet missiles located in Cuba

credit: U.S. Air Force

Finally, Khrushchev agreed to remove the nuclear missiles in exchange for the United States’ secret pledge to not invade Cuba. By the end of November, the Soviets had removed their missiles and the Cuban Missile Crisis was over, though tensions remained high. Having come so close to a nuclear war, both leaders looked for ways to calm the level of mistrust between the two nations.

On April 5, 1963, the United States and Soviet Union agreed to a “hotline,” a direct phone connection between Washington, DC, and Moscow, to avoid such conflicts in the future. It signaled a warming between the two nations, one that both Kennedy and Khrushchev hoped would lead to a better relationship.

THE END OF PROJECT MERCURY

On May 15, 1963, the Space Race continued with the final flight of Project Mercury. Following the success of Wally Schirra’s mission, astronaut Gordon Cooper’s (1927–2004) mission was to be the longest of the Mercury program, finally demonstrating that NASA could keep a person alive in space for more than a few hours. It would push Cooper and his capsule, Faith 7, to the limit.

After an uneventful launch, Cooper performed several experiments, including tracking a small beacon detached from Faith 7 and photographing Earth’s surface. With a short nap, Cooper became the first American to sleep in space after his 10th orbit. But after the 20th orbit, his capsule was showing some signs of wear. A short circuit left the automatic stabilization system without electrical power, and Cooper was unable to get any position readings from his instruments. Worse, the carbon dioxide levels in his suit were rising.

Despite mounting problems, Cooper persevered. To properly turn the craft, Cooper drew lines on the window and lined them up with familiar constellations. Using his wristwatch, he timed the firing of his retro-rockets perfectly and landed just four miles from his recovery ship in an amazing display of skill and preparation. It was a fitting end to NASA’s first spaceflight program, and cleared the way for a much more ambitious program called Gemini.

As the United States wrapped up the Mercury program, the USSR was nearing the end of the Vostok program. But before it concluded, the Chief Designer had a few more surprises for the world.

It had been almost a year since the stunning dual Vostok 3 and Vostok 4 missions, and the West wondered what the Soviets would do next. A month after the final Mercury flight, on June 14, cosmonaut Valery Bykovsky (1934–) rode into orbit aboard Vostok 5.

The first American woman in space, Sally Ride (1951–2012), wouldn’t get her chance until 1983.

|

|

With the call sign Yastreb (“Hawk”), the new cosmonaut was scheduled for a record-setting eight-day mission performing navigation and zero-gravity experiments, as well as an orbital rendezvous with Vostok 6. With a launch timed to meet up with Vostok 5, Vostok 6’s June 16 liftoff confirmed Western suspicions.

Although the launch of Vostok 6 wasn’t a surprise, its passenger was. Through the government-run media, Moscow announced another Soviet-first: Valentina Tereshkova (1937–), with the call sign Chayka (“Seagull”), was the first woman in space.

Both John Glenn and Scott Carpenter testified against admitting women into the program.

What about women in the United States? Why had men dominated the space program so far? Actually, there were women involved in a privately funded program. Known as the First Lady Astronaut Trainees (FLATs, or the Mercury 13), these women were all exceptional pilots with an interest in the space program. Despite passing many of the same physical and mental tests as the men, they were denied the chance to continue testing when a congressional hearing decided it wouldn’t change NASA’s selection criteria, which excluded anyone who did not graduate from an Air Force training school.

The Soviet Union, however, wanted to show the world that communism treated men and women equally by sending a female into space. Valentina Tereshkova was fascinated with space travel, and was eventually chosen from dozens of candidates in a secret, nationwide search. Unlike the male cosmonauts, Tereshkova wasn’t a member of the military and had no flying experience. But she was an amateur parachutist and a devoted member of the Communist Party, both useful qualities for the Soviet government and space program.

1963 postage stamp featuring Valentina Tereshkova

Like the FLATs, the female candidates in the Soviet Union faced sexism from many of their male countrymen. Of the final four women, Tereshkova was selected as the first female cosmonaut. There wouldn’t be another one for nearly 20 years, until Svetlana Savitskaya (1948–) in 1982.

With Tereshkova’s launch, the Soviet Union claimed another first. Soviet newspapers declared their society provided equal opportunity for everyone, while the Americans seemed to think only men were capable of space flight. The safe return of both cosmonauts was followed by triumphant celebrations of the newest Soviet heroes across the country. The first leg of the Space Race was over, with the Soviets again in the lead in the eyes of the world.

To learn more about the FLATs, read the article at this website. How have attitudes toward women changed since the 1960s?

•The astronauts had to request larger windows in their space capsules. Why do you think engineers didn’t think of this in the initial designs?

•Do you think gender equality is better today than it was in the United States in the 1960s?

THE EDGE OF DISASTER

In the fall of 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world to the edge of nuclear war. During that time, most Americans knew very little about what was happening behind the scenes between the United States and the Soviet Union. What was really going on?

Write down what you think each word means. What root words can you find to help you? What does the context of the word tell you?

constellation, friction, hatch, mission control, nausea, plasma, rendezvous, sexism, short circuit, and stalemate.

Compare your definitions with those of your friends or classmates. Did you all come up with the same meanings? Turn to the text and glossary if you need help.

•Create a two-part timeline of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

•What did the public know? Research newspaper articles or television broadcasts during the days of the missile crisis.

•What was going on behind the scenes? Look at what President Kennedy and other members of the government knew and how they responded.

•Compare the two timelines. Questions to consider include the following.

•How much did the public really know at the time?

•What important information was kept secret, and why?

•Do you think the public would have reacted differently had it known what the government knew?

•Was it reasonable to keep some of the facts from the public, and why or why not?

To investigate more, speak with someone who remembers the missile crisis. How much did they know at the time, and what did they think and feel in October 1962? Do they feel differently now that the details of the events are better known?