Crossing the Finish Line

Would humans have reached the moon if not for the Cold War?

The competition between the United States and the Soviet Union spurred both countries to make major strides in the science and technology needed to reach the moon. Today, scientists are still looking to the stars and beyond, and cooperation is more typical than competition.

|

|

The year 1966 was the U.S. space program’s finest. Project Gemini accomplished all its tasks, helping NASA prepare to put an American on the moon. Project Apollo was the result of lessons learned from the Mercury and Gemini missions. NASA had the knowledge and experience it needed to take America to the moon.

Although it shared a background with the earlier spacecraft, Apollo was bigger and more complex than anything that had ever flown. It consisted of two spacecraft: the command and service module and the lunar module. The command module would carry three astronauts to the moon and back, splashing down safely in the ocean. The lunar module was designed to take two of the astronauts to the moon, and return them to the command module for the trip home.

To meet President Kennedy’s challenge of putting a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth, von Braun would have to design the largest rocket the world had ever seen.

At 363 feet tall and 6.2 million pounds, the Saturn V is still the largest rocket ever to fly. Capable of generating 7.6 million pounds of thrust, it could put 130 tons into orbit, or send 50 tons to the moon.

Throughout the Mercury and Gemini programs, von Braun worked on the giant Saturn V as the Soviets first led the Space Race and then fell behind. Such a large and complicated rocket took years to develop. At the time, it was the most complex machine the United States had ever built.

Despite the lead that Gemini had given NASA, to make sure the United States was first to the moon, the Saturn V and its three stages would have to be tested all at once, a plan von Braun opposed. Usually, each stage of a rocket was tested on its own before it was joined with the others. An all-up test could save months or even years—if it worked.

THE SOVIET MONSTER ROCKET

With Sergei Korolev’s death, the Soviet space program faced a crisis. Korolev was known for his ability to bring complex and intricate ideas into a single, useful vision. Now it was up to Vasily Mishin to pull together the Soviet’s mega-rocket, the N-1.

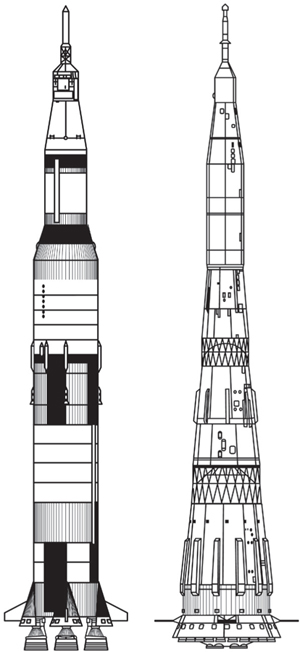

With a height of 344 feet, the five-stage N-1 was almost as tall as the Saturn V. Despite their similar size, however, the N-1 could lift only 95 tons into orbit, a bit less than the Saturn V.

The Saturn V and N-1 compared

credit: NASA

Korolev began work on the massive rocket in the early 1960s. Designed with the same goal, the N-1 and Saturn V were very different rockets. In the first stage alone, the N-1 had a complicated cluster of 30 small rocket engines, while the Saturn V first stage had just five huge engines. The other four stages of the N-1 also contained smaller and smaller clusters of rockets, making the control system extremely complex.1

It was the kind of work that the former Chief Designer excelled at, but with Korolev gone, Mishin faced the challenges of finishing his mentor’s rocket in secrecy. If the Soviets were to send cosmonauts to the moon, the N-1 needed to be a success.

APOLLO I

With the Saturn V’s first all-up test scheduled for the end of 1967, testing of the spacecraft it would carry was already underway. Mounted on a smaller Saturn IB rocket, Apollo 1 was scheduled to be the first test flight for the newly built command module.

With liftoff arranged for late February 1967, the crew of Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee (1935–1967) were sealed into the Apollo 1 command module on January 27. For hours, the crew went down its checklist with mission control, trying to work through a poor radio connection.

Crew on the launch tower tried to open the spacecraft’s hatch, but within seconds the pressure inside ruptured the hull, throwing the men back. By the time the fire was out, the crew was dead.

The tragedy caught NASA and the nation off guard. People were used to the successes of Mercury and Gemini—the loss of three astronauts was a crushing blow to both the space program and national pride. The race to the moon had taken its first lives.

Some wondered if the mission to put a man on the moon was worth the risk, which was suddenly very real.

|

|

An investigation later determined that bad wiring caused a spark inside the crew compartment during the test. In the all-oxygen atmosphere of the cabin, the fire engulfed the astronauts immediately. The command module’s wiring would need to be redesigned, and a safer mixture of oxygen and nitrogen would be used in the cabin to lessen the risk of fire. These fixes would take time.

SOYUZ 1

With America in mourning, the Soviets had an opportunity to take back the lead of the Space Race after nearly two years on the ground. Soyuz was the next-generation spacecraft, designed to carry up to three cosmonauts on long journeys into space. Like Gemini, Soyuz could change its orbit and even dock with another spacecraft. But unlike Gemini, Soyuz was also meant to go to the moon.

Brezhnev, eager to reassert his country’s lead in space, called on Vasily Mishin to follow in Korolev’s footsteps and pull off something spectacular. Moscow wanted the first Soyuz flight to be a rendezvous in space with crews switching crafts for the return home.

But there were serious problems. Only two of the first five unmanned Soyuz flights were successful, and engineers and cosmonauts alike kept discovering dangerous issues with the craft. Yuri Gagarin (1934–1968), Soviet hero and backup pilot for the flight, wrote a letter asking to delay the flight until the problems were fixed. Determined, Moscow ignored the warnings. Brezhnev was confident that the issues would be overcome.

On April 23, 1967, Soyuz 1 lifted off with cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov onboard. Right away, there were problems. One of the craft’s solar panels failed, leaving it short on electrical power. Communication between the ground and Komarov was plagued with static. The automatic stabilization system failed. After just 18 orbits, the decision was made to bring Komarov home early.

Soyuz 1 was supposed to rendezvous with the crew of Soyuz 2, but thunderstorms ended up canceling the second launch, possibly saving the lives of the crew.

But the problems didn’t end. Once the spacecraft had slowed after reentry, the main parachute failed to open. As the capsule plummeted, Komarov activated the reserve chute, but that failed, too. When the landing rockets didn’t fire, Soyuz 1 hit the ground at nearly 100 miles per hour. When rescue teams arrived, the landing rockets suddenly roared to life as the capsule lay on the ground. By the time the fire was out, Komarov was dead.

The death of Komarov was a terrible disaster and a reminder of just how difficult spaceflight could be. The Soviets, too, had become used to success. Now, both nations needed to recover from their tragedies. The moon seemed farther away than ever.

A DEEPENING WAR

On the lunar new year of January 30, 1968, North Vietnamese troops launched a surprise, nationwide attack on South Vietnam. Guerrilla fighters attacked the U.S. embassy in Saigon, killing many. U.S. and South Vietnamese combat troops managed to fend off the offensive, but the loss of American lives brought stronger calls for an end to the United States’ involvement in Vietnam.

With confidence in his administration severely damaged, Lyndon B. Johnson decided not to run for reelection and to instead focus on fighting a war that seemed to have no end in sight. More than half a million American soldiers were already fighting alongside the South Vietnamese, and more were on the way. Soviet and Chinese officials continued to issue warnings to the United States, cautioning that the war could grow larger.

That summer, the Soviets faced their own struggles on the world stage. On August 20, forces led by the Soviet military invaded Czechoslovakia to stop the country from reforming its government and economy. This crackdown in Eastern Europe spread fear of Soviet aggression throughout the West, and a planned summit between the United States and the USSR was canceled. Already stuck in an unpopular war in Vietnam, the United States could only condemn the Soviet Union’s actions.

Both nations hoped that a return to space could provide the world with some relief from the realities on Earth.

|

|

Despite the Apollo and Soyuz disasters, the United States and the Soviet Union continued testing their spacecraft with unmanned flights as the race to the moon heated up. On November 9, 1967, the first all-up flight of the Saturn V lifted off from launch pad 39A with an earth-shaking roar and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean almost nine hours later.

Not to be outdone, the Soviets responded to the Americans with the launch of Zond 4 on March 2, 1968. The slimmed-down Soyuz capsule flew 186,000 miles from Earth, three quarters of the distance to the moon, before it self-destructed during reentry.

Just a month later, a second Saturn V flight was less successful than the first when Apollo 6 experienced engine problems on its second and third stages. But despite its trouble, the rocket was able to complete its mission and was considered a success. The risky all-up testing had saved NASA a lot of time and effort, but nobody was certain if it would be enough to win the race.

On September 2, Zond 5 carried a collection of tortoises and other creatures on a flight around the moon and returned them to Earth with a splashdown in the Indian Ocean. It was another impressive feat by the Soviets, and the United States feared that the next launch from Kazakhstan might carry cosmonauts on a trip around the moon before NASA could even put a crew into orbit.

While tests and maneuvers took up much of the crew’s schedule, the astronauts still had time for a few television broadcasts.

|

|

RETURN TO FLIGHT

To a national sigh of relief, Apollo 7 rocketed into orbit on October 11, 1968, with astronauts Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele (1930–1987) and Walt Cunningham (1932–) aboard. The smaller Saturn IB rocket was used to carry the redesigned command module, with plans to test the space-worthiness of the new craft in orbit. Apollo 7 was the first manned flight since the Apollo and Soyuz tragedies, and any problems could mean even more delays.

The 10-day flight was packed with tests and experiments. The first flight of the command module meant exhaustive work to make sure the redesigned capsule worked properly.

Days after Apollo 7’s flight, the Soviets returned to crewed spaceflight with the launch of Soyuz 3. Once in orbit, cosmonaut Georgy Beregovoy (1921–1995) guided the redesigned craft to a rendezvous with Soyuz 2, its unmanned docking target. Unfortunately, he was unable to connect the two spacecraft, and had to call the mission off when his fuel ran low.

Two pieces were still missing from both programs: a lunar lander and the giant rocket that would send it to the moon.

A DARING PLAN

Apollo 7’s command module test flight had gone so well that the next mission, Apollo 8, was set to test the craft that would carry astronauts to and from the surface of the moon. The lunar module was nothing like any other spacecraft before it. Unlike the streamlined capsules of Apollo or the smooth spheres of Soyuz, the lunar module looked like a large, awkward spider covered in aluminum foil.

With barely enough room for two, the lunar module was small and light, but it wasn’t light enough. There were also problems with its ascent motor, the rocket that would carry the astronauts from the lunar surface back to the command module. If it wasn’t ready in time for Apollo 8, it could put the entire program behind schedule.

After the Zond missions, the United States was worried that a Soviet manned mission around the moon was next. NASA came up with a brilliant plan. If the lunar module wasn’t ready, Apollo 8 would launch without it, giving engineers more time to work out the kinks. But Apollo 8 wouldn’t be a copy of Apollo 7’s flight. To beat the Soviets, Apollo 8 would carry the first people to circle the moon.

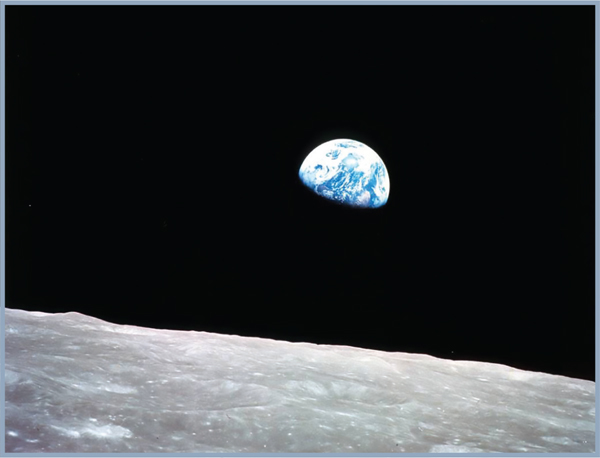

On December 21, 1968, Apollo 8 lifted off with Jim Lovell, Bill Anders (1933–), and Frank Borman, the first astronauts to ride atop a Saturn V. A perfect burn of their main engine set them on a course to the moon, and three days later, the crew entered lunar orbit.

The mood on Earth and inside the Apollo 8 capsule as it orbited the moon was joyous. No one had ever been so far from home.

|

|

The astronauts were celebrated as heroes. Millions across the globe were inspired by the flight, but for NASA, it was much more than an inspirational sightseeing trip. Apollo 8 showed that the United States could send people to the moon and back—the only thing left was the landing and the small, spidery spacecraft needed to do it.

Earthrise: The view from the moon

credit: NASA

With the lunar module finally ready at the beginning of 1969, Apollo 9’s crew of David Scott, Alan Bean (1932–), and Dick Gordon were assigned to put it through its paces in Earth’s orbit. After liftoff on March 3, the astronauts tested the lunar module exhaustively. Stacked beneath the command module at launch, the lunar module had to be pulled from its protective covering, which was a difficult maneuver. The ascent and descent engines worked well, and the crew simulated the lunar module’s return from the lunar surface and docking with the command module.

After Apollo 8’s incredible flight, the world waited for the Soviet’s response, but the former leaders in the Space Race were strangely silent.

|

|

After more than a week of testing, the lunar module had passed all of its tests. With everything looking ready, the next mission would return to the moon with the lunar module in tow.

SO FAR AND SO CLOSE

The liftoff of Apollo 10 on May 18 was the fourth successful launch in just seven months, an incredible achievement for such a complicated system. For the first time, all of the pieces of Apollo were traveling toward the moon. Color television broadcasts sent back spectacular pictures of the crew, the spacecraft, the earth, and the moon.

Despite having all the equipment, Apollo 10 would not have been able to land on the moon. For this trip, the lunar module had only enough fuel to approach the surface, not enough to land.

After safely entering lunar orbit, astronauts Thomas Stafford and Eugene Cernan left John Young behind and made their way toward the surface of the moon. At just less than 9 miles from the moon, Cernan stopped their descent over a future landing spot in the Sea of Tranquility before heading back to Young in the command module for their trip home.

Apollo 10 had done everything short of actually landing men on the moon. The time for tests and rehearsals was over. The next scheduled mission, Apollo 11, would go for the finish line.

A MAN ON THE MOON

On July 16, 1969, a Saturn V carrying Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral with the hopes and dreams of a nation riding along with them.

Once all systems checked out in orbit, the astronauts were off to the moon. After a three-day cruise to lunar orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin boarded the Eagle lunar module and began their descent to the surface. As they approached the landing site, computer alarms sounded. Despite the alarm sounding several more times, mission control in Houston, Texas, assured the astronauts that they could ignore it. They continued their descent.

Experience the moon landing in real time with CBS coverage of the event at this website. How might it have felt to watch this as it was happening?

As the landing site came in view, the astronauts discovered an issue. Large boulders dotted the area, making it too dangerous for the fragile lunar module to touch down. At just 1,000 feet above the boulders, Armstrong took over control from the landing computer. Carefully, he looked for a suitable place to set down, very aware that he had less than a minute of fuel remaining and even less if the landing was called off.

Finally, an opening appeared, and he piloted the Eagle module accordingly. Dust stirred up from the rocket motor obscured their view. The world waited. Armstrong spoke:

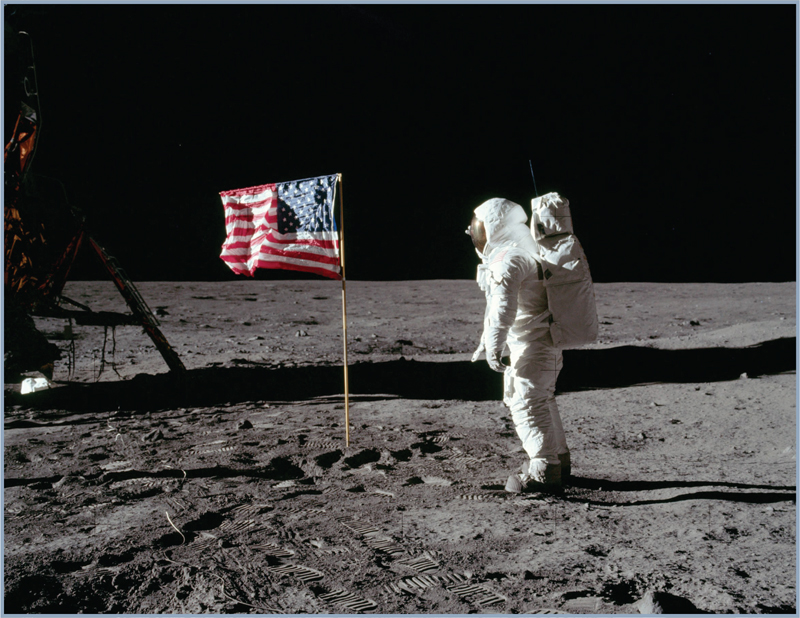

After checking the condition of the craft, Armstrong donned his suit and made his way from the hatch to the ladder. A television camera mounted on the outside of the landing module broadcast the moment when his boots first touched lunar soil. “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” he said.2

A nation, and the world, rejoiced. More than half a billion people witnessed the event on television, with many more listening by radio. The entire world celebrated. For von Braun, it was the achievement of a lifelong dream, one he’d had since his days reading about rockets and spaceships as a boy in Germany.

Buzz Aldrin salutes the American flag on the moon

credit: NASA

After 21 hours on the surface, the first men on the moon returned to their tiny spacecraft to begin their return journey. They took with them samples from the lunar surface, and left behind several experiments, hundreds of boot prints, and the American flag.

THE END OF THE RACE

With Neil Armstrong’s step, America crossed the finish line and won the Space Race. Six more missions to the moon would follow, and five would be successful. A total of 12 people walked on the moon, carrying out experiments, collecting samples, and even driving across the gray landscape in an lunar rover.

The Soviets had insisted to the world that they, too, would land on the moon, but it was not to be. Korolev’s N-1 flew several more times, each flight ending in massive explosions. Every unsuccessful test was a costly blow, and the fourth and final explosion near the end of 1972 signaled the end of the N-1 and the Soviets’ manned lunar program. Despite their disappointment at not making it to the moon, the Soviet cosmonauts congratulated the Americans for bravery and achievement. They knew just how difficult and dangerous the race had been.

The success of the program had many dreaming of even greater missions, perhaps with the cooperation of the Soviets. A lunar base and a mission to Mars were discussed. But after Apollo 13, with an onboard explosion that nearly resulted in more tragedy, interest in the lunar program declined. The expense was too great. Originally set to consist of missions to the moon, the Apollo 18–20 missions were canceled. The cost of continuing to run a race after crossing the finish line was too great.

In 1975, the two former competitors performed a joint mission called the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP). An Apollo command module and Soyuz spacecraft docked in orbit, with the crews shaking hands and exchanging gifts.

It was a strong statement of cooperation between the two countries after such a long and difficult race, but both nations went their separate ways after the mission. The United States focused on its reusable Space Shuttle while the Soviets assembled a number of small but highly successful space stations in Earth’s orbit. The next collaboration wouldn’t happen until 1994, when the Space Shuttle docked with the Russian Mir station.

Despite popular opinion, the Space Race was as much about the politics and posturing of the Cold War as it was humanity’s drive to build and explore.

Today’s astronauts risk their lives for science and exploration more than national pride or to achieve a political goal. But the fact that they’re able to do so is a direct result of the tensions and fears of the Cold War and the decisions made by those with more than pure exploration and scientific advancement on their minds.

Where would we be today if the Soviet Union and the United States had not faced off against each other in a competition of will, drive, and ambition?

•Why is the photograph of Earth rising over the moon such an iconic image? What does it mean to you?

•Do you think another exploration competition similar to the Space Race could happen today? Why or why not?

•What happens when politically divided countries find common interests in the sciences or arts? Can you think of examples of this today?

RETURN ON INVESTMENT

For both the United States and the Soviet Union, the cost of the Space Race was immense. Billions of dollars were invested that some critics feel could have been better spent on Earth. Yet many important advancements, such as GPS navigation and satellite communication, were direct results of the space program.

Write down what you think each word means. What root words can you find to help you? What does the context of the word tell you?

collaboration, GPS navigation, rover, simulate, space station, summit, superpower, and thrust.

Compare your definitions with those of your friends or classmates. Did you all come up with the same meanings? Turn to the text and glossary if you need help.

•Do some research on the costs of the space program. What are your views on the cost of the space program? Was it worth the expense?

•Compose your argument, and support it with facts. Here are some questions to consider.

•How did the Space Race harm or benefit each country?

•If the Space Race had not taken place, where would we be now in terms of space exploration?

•Now, take the opposite side. What are the opposing arguments?

To investigate more, debate your argument with someone else. What are some of their points? How will you refute those points?

The Space Race ended with a walk on the moon. What might have happened if the Soviet Union had won the race? What might have happened if the U.S. space program had continued to send people beyond Earth’s orbit? Do some brainstorming and come up with some ideas!

•Imagine the Soviet Union was the first country to land a man on the moon. Write a short story that imagines characters and scenes in an alternative history in which the Soviet Union won the Space Race.

•How would that have impacted the world?

•How would the United States and the world have reacted?

•How might the world we live in today be different?

•Imagine that the Space Race didn’t end with a walk on the moon and the United States kept the Apollo program going. Research the Apollo missions that were never flown and find out about plans to travel to other planets. Write a short story that takes place during one of these imaginary missions.

•How might these missions have changed the world?

•What might have been discovered during these scientific explorations?

To investigate more, read a science fiction book that explores humans on other planets. What did the author imagine? Was it different from your own thoughts? How do fiction writers take factual information and use it to create stories?

Private companies are now able to lift satellites into orbit and deliver supplies to the International Space Station—efforts once achievable only by wealthy and powerful governments.

Today, the International Space Station, or ISS, is an example of peaceful cooperation in space. Fifteen nations—including the United States and Russia—helped design and build the outpost to perform experiments and study how spaceflight affects the human body. You can learn more about the ISS here.

•Research at least two companies involved in private spaceflight, such as Virgin Galactic, Space X, and Blue Origin. You can read about the three companies here.

•Compare the companies. What are their plans to put people and things into space?

•Putting people and things into space is expensive and dangerous. Do you feel that private companies can handle the challenges of spaceflight? Why or why not?

•Some companies plan to take paying customers into space. Would you take a ride on a private rocket?

To investigate more, consider whether the danger and cost of space exploration is worth it. Compare your answer with others.